FLYING ELEPHANTS

North West trophy hunting, the ghost and the dodgy deal — how Namibian tuskers got to Middle East zoos

The hidden hand of North West’s canned hunting industry is involved in the controversial export of Namibian elephants.

A four-month investigation has found that North West’s canned hunting industry was behind the controversial export of 24 wild-caught Namibian desert elephants to the United Arab Emirates (UAE) in late February 2022. It was closely supported by the top officials of Namibia’s Ministry of Environment, Forestry and Tourism (MEFT).

The exported herd was among 57 elephants sold by a tender issued late in December 2020 by MEFT to catch and remove 170 elephants ranging outside of Namibia’s national parks, ostensibly to alleviate “rampant” human-elephant conflict.

A paper trail going back 40 years revealed how the canned hunting industry had taken advantage of a growing information gap between South Africa and Namibia’s regulatory authorities to create a ghost company that the controversial deal was run through to hide its true beneficiaries.

The deal not only robbed the Namibian state treasury of at least $2.3-million (about R33.3-million), but left the core problem of crop damage by elephants unresolved while deeply impacting the fragile ecology and ecotourism industry of the northwestern Kunene Region, also known as The Arid Eden.

The elephants being loaded at the Hosea Kutako International Airport outside Windhoek on 25 February 2022 en route to three zoos in the United Arab Emirates. (Photo: Supplied)

“This sale will damage the ecotourism that has contributed revenue to the Kunene community’s economy,” Dr Keith Lindsay and two co-authors of the African Elephant Coalition wrote in a commentary on the sale.

“If the elephants disappear, other wildlife populations could also become a thing of the past. The loss of the elephants poses a risk that land could be lost for natural resources as more and more is taken over for commercial farming within the region.”

None of this appeared to be of concern to the Namibian government, though. In August 2021, Environment, Forestry and Tourism Minister Pohamba Shifeta announced that 57 elephants were “successfully sold” to one local and two foreign buyers, but refused to disclose who the bidders were by claiming contractual confidentiality.

This was to prove patently untrue: successful local bidder Dr Rudie van Vuuren of the Na’ankusê Wildlife Sanctuary subsequently publicly admitted that the secrecy surrounding the elephant tender was imposed by MEFT. “We wanted to go public, but the ministry asked us not to do so,” he said during a televised panel discussion on the controversial deal two weeks later.

So far, 37 elephants — two incomplete families — were caught in the arid northwestern region and removed. Fifteen were moved from Omajete to the new R400-million TimBila Lodge operated by the privately owned animal charity Na’ankusê and run by Van Vuuren on behalf of a mysterious Belgian investor, and 22 of the Kamanjab herd sold to canned hunting operator Gerrie Odendaal and his partners.

The remaining 20 elephants allocated to the other mystery foreign buyer had not been paid for a year later and remained free at the time of writing, MEFT’s executive director, Teofilus Nghitilila, confirmed at a 22 February press conference. He insisted that these 20 elephants were not destined for China, as widely speculated.

Shifeta said the elephant tender had netted the ministry R4.4-million — R1.1-million from Na’ankusê and R3.3-million from the UAE deal. However, it subsequently emerged that the UAE deal paid the local middlemen at least $3.3-million (about R50-million) in gross profits, of which only $950,000 (about R14-million) was reportedly paid over locally to Odendaal and his partners. The balance appears to have been pocketed by a foreign-registered ghost company called JJO Bees (Pty) Ltd — but more on this later.

MEFT has repeatedly and strenuously denied any allegations of malfeasance, insisting that its decisions were motivated only by its efforts to manage human-animal conflict in the rural, communal areas in the interest of long-term conservation.

‘Hunting conservation’ approach

The picture is further complicated by the fact that local conservation’s voice is dominated by foreign interests aligned to the WWF-funded “hunting conservation” approach that has seen Namibia open all its national parks except Etosha to trophy hunting since the late 1990s.

This approach has led to overhunting which, combined with the crippling 2013-18 drought, has decimated wildlife numbers in all communal areas operating under the official Community-Based Natural Resource Management model since 2012.

This relentless drive for profit at the expense of sustainable conservation was most visible in the export of 22 wild-caught elephants and two newborn calves to the Al Ain and Al Sharjah zoos in the UAE in late February.

Not only did this leave the alleged human-elephant conflict problem (MEFT’s formal motivation for this deal) in respect of crop damages largely unresolved, but the manner in which the deal was structured strongly suggested official complicity in the illegal externalisation of government revenue from conservation.

According to the 32-nation African Elephant Coalition, this export taking place a day before a meeting of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES) in France was to discuss the transaction, further raised very serious questions about Namibia’s international conservation credentials.

MEFT’s Nghitilila, at a press conference held a week earlier to “clarify misconceptions” around the controversial and secretive deal, claimed their decision was legitimised in terms of Article III of the legally binding CITES convention.

As in the past when Namibia exported wild-caught elephants to Cuba and Mexico in 2012, MEFT had selectively used an Appendix I concession to allow for the efficient transfer of specimens between bona fide, in situ conservation programmes.

MEFT had used a loophole in the CITES legal mechanisms for transferring biological samples to smuggle a whole herd of elephants. Nghitilila’s assertion of compliance under Article III appeared to rest solely on the fact that he had issued the CITES permits to the game dealer Gerrie Odendaal and partners for the export before the elephants were captured in September 2021.

Nghitilila refused to respond to questions about whether he considered a commercial zoo and African theme park in a non-range country as bona fide, in situ African elephant conservation programmes, or why MEFT had not sold the elephants directly to the Middle East clients itself to maximise official revenue accruing to the Game Products Trust Fund.

When pressed on these points and asked to disclose the original tender documents and CITES permits he had issued, Nghitilila banned this reporter from the ministry’s official media platforms and from receiving any official ministerial press releases.

Ten days before this, a colleague and I were arrested by the Gobabis police and charged with trespassing by flying a drone over the elephant boma on Odendaal’s Mooiplaas farm close to the Botswana border, where he is also breeding white rhinos for the trophy hunting industry on behalf of a shadowy syndicate of speculators.

This arrest, in clear violation of constitutional rights of freedom of the press and the public interest in this matter, came after Odendaal and MEFT had stonewalled a formal request made a week earlier and in person to Odendaal on his farm to verify the presence and specifics of the Kamanjab elephant herd on Mooiplaas first-hand.

An analysis of the official MEFT documentation and statements, read together with corporate and property records for the parties involved, brought to light an altogether different picture than the official version.

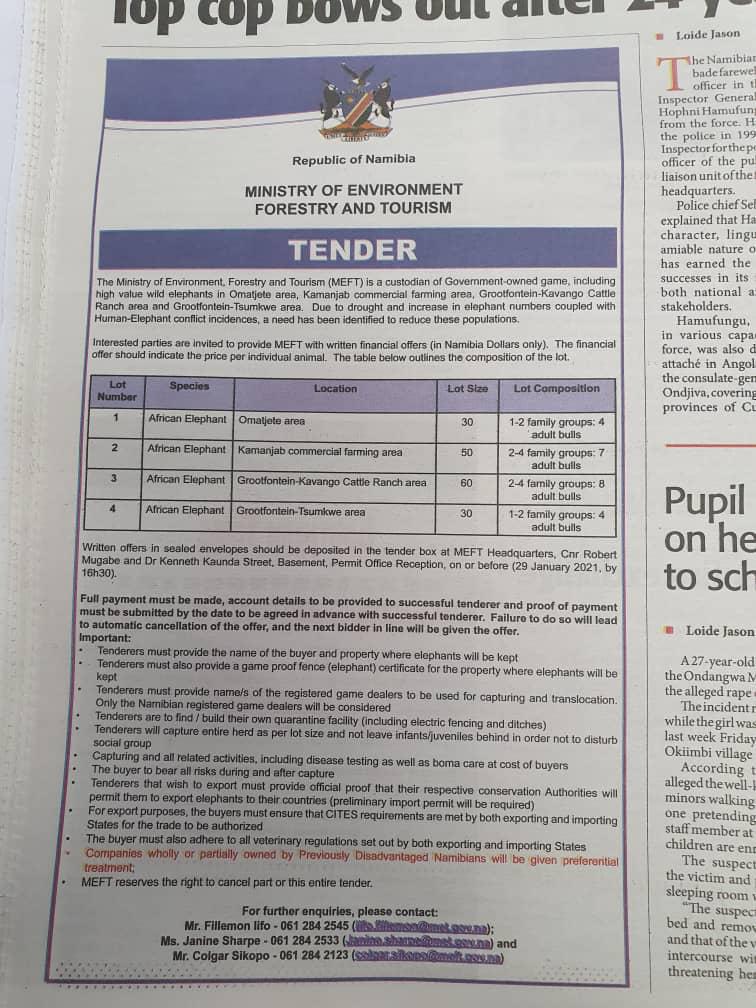

Copy of the original advert as run in December 2020 to solicit offers for the capture and removal of 170 wild elephants outside of Namibia’s parks. (Photo: Supplied)

For starters, the original advert for the tender (published in only the state-owned New Era newspaper in late December 2020) specified that any bidder intending to export the elephants would have to present written authorisation and CITES clearance from both exporting and importing countries in the form of a pre-permit issued by the bidder’s national conservation authority.

This appeared to be what Nghitilila had meant by his alleged CITES Article III authorisation, but which is only applicable to animals already in captivity.

This also implied that Odendaal and his secret partners would have had to obtain this CITES pre-permit from Nghitilila well in advance of the tender’s closing date of 29 January 2021. This meant that the ministry’s top officials not only knew that the elephants were going to be sold to buyers in the UAE, but actively assisted Odendaal and company to do so at the expense of government revenues in excess of R36-million.

The tender advert also made it clear that any prospective bidder needed to include a black empowerment shareholding to ensure success. At this point things got really interesting in a complicated manner, bringing to light a shadowy cabal of canned hunting interests in the UAE deal.

Shifeta’s August 2021 disclosure that one lot of 22 elephants of 42 allocated was to a foreign buyer was not even halfway true; though technically correct, it further emerged.

At MEFT’s press conference held a week before the Kamanjab herd was flown to Dubai on a Boeing 747 chartered from the Chinese-owned 360Express company, MEFT’s deputy director of scientific services, Kenneth /Uiseb, let it slip that this bid was not awarded to Odendaal’s Go Hunt Namibia safari outfitter as previously reported, but instead to Nuwebegin Boerdery CC (New Start Farming).

/Uiseb played a key supporting role in the UAE debacle: not only is he responsible for fudging Namibia’s wildly exaggerated claim of a population of 24,000 permanently resident elephants (the real figure is believed to be less than a quarter of that), but is believed to be one of three families resettled on the Lusthof farm where the Kamanjab herd was captured.

As a matter of policy, the Ministry of Lands refuses to disclose such beneficiaries, a source of much frustration for local opposition parties who claim that such privileged access to state-owned farms was key to the corruption that has crippled land reform efforts.

/Uiseb, for his part, avoided answering to this allegation, insisting that he was not the director of scientific services as averred (he is the deputy) and that the entire allegation therefore had to be rejected out of hand.

/Uiseb’s wild-eyed interjection at the 22 February press conference that the “foreign” bidder was Nuwebegin Boerdery and not Go Hunt Namibia as previously reported, was seemingly more intended to confuse than clarify questions from reporters in this regard. But it opened a fruitful line of investigation.

Nuwebegin was also not a foreign company, but was to lead to a company originally registered in South Africa in 1974, JJO Bees (Pty) Ltd, and a cattle speculator named Johannes Jacobus Christiaan Oosthuizen from Vryburg in what was then still known as the Northern Cape and now part of North West.

These family names — Johannes Jacobus Christiaan — were to emerge like a red thread among the close corporations and beneficiaries of the elephant export deal.

In 1981, Oosthuizen used JJO Bees to acquire two adjoining farms, Noordburg and Mooiplaas, situated east of Gobabis in prime cattle country close to the Botswana border, with two loans from the state-owned Land Bank, now Agribank.

Elephant boma

Mooiplaas, it should be noted, was where the elephant boma was built in preparation for the Kamanjab elephant herd being exported to the UAE.

Oosthuizen claimed his farming operations in South Africa and in the then South West Africa were operating at a loss, according to financial statements on file for JJO Bees. However, deeds office records showed that he had repaid both loans over the next 10 years.

Following Namibian independence on 21 March 1990, the Registrar of Companies in Pretoria notified Oosthuizen in 1991 that JJO Bees, as an externally registered company showing nil tax returns, was to be deregistered. The deregistration was completed in 1993 by way of an official notification in the South African Government Gazette.

Four years later, in 1997, Oosthuizen filed a Notice of Deregistration with the now-independent Namibian Registrar of Companies as well, stating that JJO Bees had no assets or liabilities and did not intend carrying on doing business in Namibia, in spite of it owning two prime farms.

This appeared to be because in the previous year (1996), Oosthuizen had set up two new close corporations — Nuwebegin Boerdery CC and Mooiplaas CC — which owned the farms Noordburg and Mooiplaas, respectively.

Crucially, both CCs recorded Noordburg as their main place of business, with Mooiplaas funded by a R1-million contribution from Oosthuizen. This was unusual, since a close corporation, as a poor man’s corporate entity, does not legally require more than a total contribution of R100, and since Oosthuizen had paid only R198,000 for the two portions that made up Mooiplaas originally.

JJO Bees’s deregistration, however, created a legal problem in the transfer of these two properties for Oosthuizen. In 1998, he tried to have JJO Bees reinstated in South Africa, according to a copy of an application to the High Court in Pretoria in JJO Bees’s company file.

Whether this application was successful is not clear — no record of the outcome or such a case being heard in Pretoria could be found. Oosthuizen would have had to show proof of tax returns for JJO Bees since 1991, and commercial matters older than two years seldom get admitted to the court roll, a Windhoek lawyer explained.

Oosthuizen appeared instead to have taken advantage of the growing communication gap between Pretoria and Windhoek: just an unsigned copy of the application appeared to be enough to satisfy the Namibian Registrar that JJO Bees was still active in South Africa.

Currently, JJO Bees is still maintained as a foreign-owned company in Namibia, even though a search of South African company records yielded no results for JJO Bees (Pty) Ltd.

Tax dodge

This appeared to have largely been a tax dodge: even though Oosthuizen had claimed to the Namibian Registrar that JJO Bees had no assets or liabilities, his 1998 Pretoria High Court application stated that the company still owned properties and farming equipment that he wanted to dispose of.

In fact, in the 45 years of its existence, JJO Bees had not once recorded a profit, records showed: its Namibian auditors, SGA (Swart Grant Angula), similarly kept filing nil returns on its behalf from 2005 to 2007. No entries were made in the file after that, though.

In effect, JJO Bees was now a ghost company: still legally registered in Namibia as a foreign-owned entity, but with its South African corporate owner having ceased to exist nearly 30 years ago.

Who JJO Bees’s beneficial owners were now was not clear: SGA’s secretarial services department claimed they had resigned as its auditors, although there is no formal notification to this effect on file.

Meanwhile, Mooiplaas CC’s ownership was amended in March 2003, reflecting JJC Oosthuizen Sr as the 51% owner, with Gerrie Odendaal and a younger brother, one Jacobus Johannes Odendaal, each holding 24%.

All of these CCs appear to have been set up by conveyancer Johannes Christiaan Gouws of Windhoek-based legal firm Quarmby, Fischer & Pfeifer, who in June 2003 also handled the sale of the farm Noordburg to Elliot and Gisela Hiskia for R1.5-million, financed by an Agribank Affirmative Loan Scheme bond of R1,530,300.

Originally, Oosthuizen had paid R145,000 for Noordburg, repaid his loan — yet reported making a loss on his farming operations from 1977 to 2007, according to the financial records submitted on his behalf.

In November 2007, Mooiplaas CC’s ownership was further amended to reflect four members, each with 25%: Gerrie Odendaal and his younger brother Rudolph Odendaal, Oosthuizen Sr’s young brother Rudolph Ludwig Oosthuizen and a Rosa Petra Bester.

All of them are South African and from North West, although Rudolph Oosthuizen — who appears to have inherited JJO Bees from his older brother — also died on 18 January 2014, according to a death certificate in the JJO Bees file.

Nuwebegin CC’s founding statement was amended on 1 June 2011 to reflect that the nature of its business was now “Livestock and game farming, hunting, guest accommodation (bed and breakfast), tour operator, tourism advisory services, letting and leasing of fixed and moveable assets, general dealer and ancillary activities”.

Nuwebegin’s business address was listed as that of auditors SGA (Swart Grant Angula) in Windhoek, who also took over as accountants of JJO Bees in 2005. SGA partner WH Boshoff also filed nil returns for the company for the 2005 to 2007 financial years.

Two of the Namibian Kamanjab elephant herd calves left behind by the capture team. The original tender called for only whole families to be removed. (Photo: Supplied)

Trophy hunting business

A 7 February visit to Mooiplaas confirmed that Odendaal was operating a trophy hunting business there. He also boasted that he was “the biggest rhino breeder in Namibia”, providing trophy rhinos to the trophy hunting industry. There is, however, no general dealer on his farm; the only general dealer is on the neighbouring Noordburg farm, it was confirmed.

A chance encounter in the Noordburg General Dealer on 12 February with the Hiskia couple’s son, Elliot Jnr, a former investment manager, was to provide the final clues.

Elliot Hiskia Jnr confirmed that he took over the running of Noordburg in 2014. People were amazed that he could make a good living on the relatively small (3,000ha) farm, he said, adding that he was related through his mother to former first lady Penehupifo Pohamba.

So, was he Odendaal’s secret BEE partner? I asked him for an interview and permission to view the elephant boma on Mooiplaas from Noordburg. When he then excused himself to “go do something urgent” and left hurriedly, I realised that he was going to report our presence to the MEFT head office and Odendaal.

Subsequent events confirmed this suspicion: MEFT spokesperson Romeo Muyunda told The Namibian newspaper the next day that my arrest in Gobabis, 120km away, had been prompted by a telephonic tip-off.

Since 12 February, Odendaal has refused to answer any questions. However, the inferred connection between Elliot Hiskia and the UAE elephant deal was now clear: he appeared to have been the BEE partner to Nuwebegin’s bid for the Kamanjab elephants.

Which left only two unanswered questions: who was the second foreign buyer, and who is TimBila’s BEE partner?

Not only did this deal rob cash-strapped MEFT of R33.3-million, but two calves born subsequently on Mooiplaas were basically given away for free and another calf separated from its mother was left behind in Kamanjab, contrary to MEFT’s insistence that only whole families were to be captured. It appeared their fate was to be turned into petting zoo attractions, said Michele Pickover of the EMS Foundation.

“Elephants — because they are the biggest land-based animals — are seen by zoos as commercial drawcards and ‘cash cows’. And baby elephants on exhibition, even more so,” she said. “Some zoos — like the ones in China and the UAE — also allow interactions with elephants and this form of commercial exploitation is even more lucrative.

“For an elephant to interact with humans, they have to be ‘trained’, and they have to do this when they are very young. People do not see what this entails because it happens behind the scenes, but it is a very brutal process.

“Elephants removed and ‘broken’ by trauma and trained by fear and/or force are exceedingly capable of retaliating much, much later [against] the humans who might be interacting with them,” she wrote.

The biggest loser in all this is Namibia’s reputation as an “African conservation success story”, as the ministry and the WWF often proclaim to anyone who will listen. In hindsight, this reputation appears to be totally undeserved. DM/OBP

[hearken id=”daily-maverick/9419″]

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

The love of money destroys Africa,most leaders are only in it for money, and unscrupulous persona like Odendaal cash in.Money from China and UAE who are facilitators to destroying Nambia and Africa’s wildlife.All groupings or individuals mentioned ,should have there assets frozen.What is the chance.Humanity and very rich people /individuals offer Africa’s wildlife to the Mammon church!!!!