CULINARY PHYSICS

The Pretoria lab where food wonders never cease

In a University of Pretoria lab, students take a hybrid degree pairing food studies with science, and chefs graduate as food scientists.

I am in a University of Pretoria lab, making four different shades of chocolate fudges with four young women decked out as chefs. They’re in their fourth year, Honours graduates-to-be. But they’ll graduate as real scientists, having completed a combination of Culinary Arts with Food Science. It’s an academic wonder of the world.

The guinea pigs were two UP students who’ve already completed the hybrid degree. But these four young women surrounding me today are the first group, right here in Africa, following the first two into food history with the only such degree introduced among a very few other, slightly differing versions in the world.

The long, techy and gleaming central lab counter. (Photo: Marie-Lais Emond)

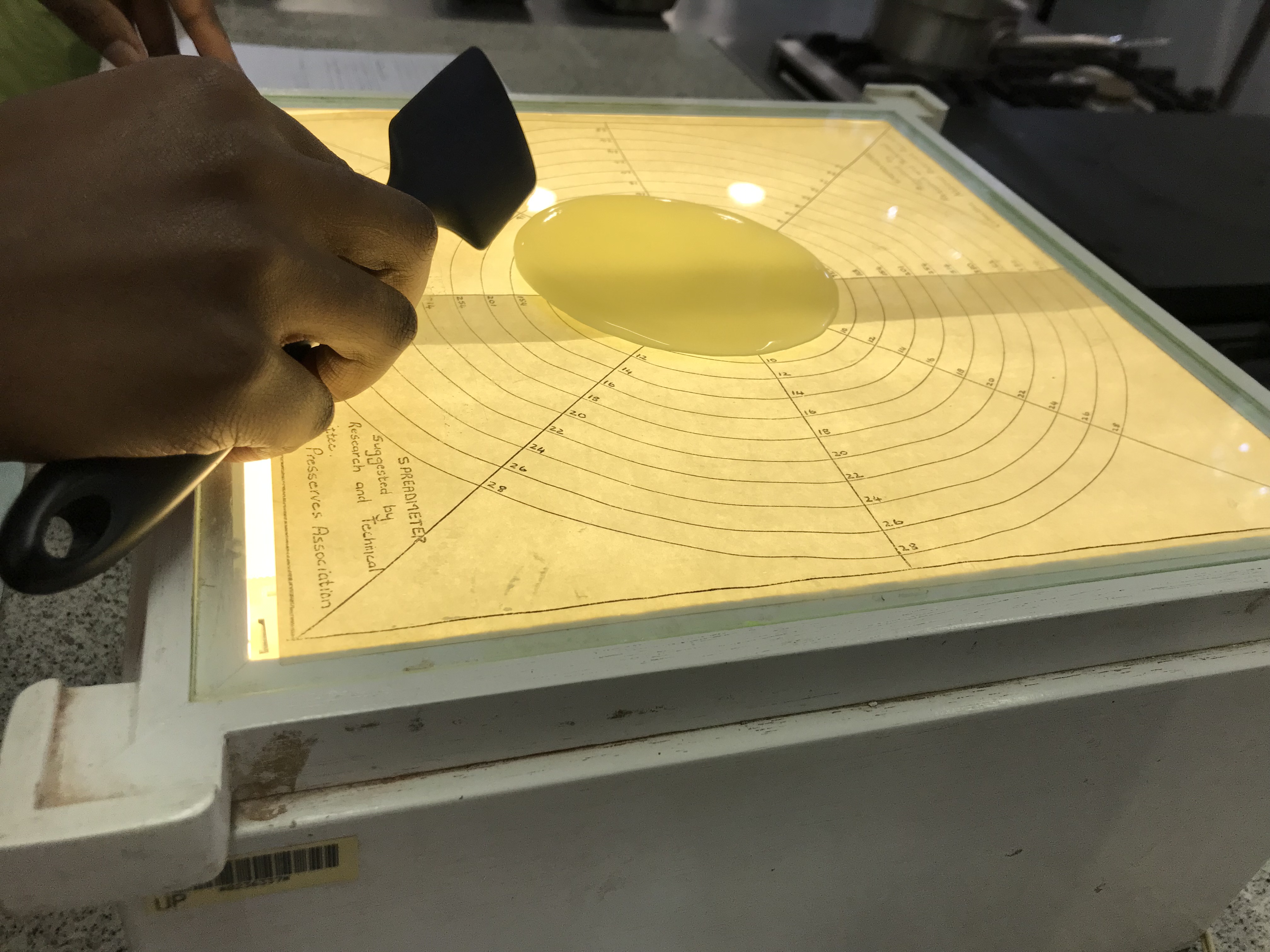

The first chocolate fudges using white Cadbury Dream chocolate are setting in small loaf tins on the long, techy and gleaming central laboratory counter. One has been set aside. It was cooked slightly too long and has caramelised to a light tan. “The one that probably tastes the best,” says Jenna, ruefully. Then she measures and pours a paler version onto a Spreadmeter light box with concentric circles marked on the lit screen. She records the viscosity of spreadability in millimetres.

This is the group’s lab day and the fudge making, though of a perfect standard, is not quite as important as the tests being and going to be run on it. It’s but one example of a day in the group’s academic science year and I just happen to be here on this one. Other days of the week are for other disciplines on both sides, culinary arts and food science.

I wonder about chefs and extra science. There’s the thing that chefs mention about the science of cooking and their moment of realisation about that. It’s the one day when they just know they are chefs who understand their food. They know how colloidal suspensions work in their sauces, how the Maillard effect affects meat and when and why and for what. Up till then they were good cooks without the scientific knowledge. But this is even further science, the science of chemistry really.

In the lab, the tins of the palest chocolate fudge, made with the white chocolate, are set. Before the contents of the three tins of milk chocolate fudge, made with Cadbury’s dairy milk, are poured into each tin, they’re measured and noted too. Three is a useful number for testing, cross experiments, for finding an average, giving a result. They’re all first measured out with the castor sugar and milk in bowls and cooked, one by one. The usual white sugar has been replaced by castor sugar and the recipe has replaced a previous one. This test fudge uses four ingredients and is simple in the making.

Measuring the white chocolate’s viscosity on the Spreadmeter. (Photo: Marie-Lais Emond)

I ask all four if they see themselves as chefs in the future.

“Maybe molecular gastronomy…” says one, thoughtfully, with her head to one side. Two agree they’d prefer a career somewhere in development.

“I’m not going to waste all my chemistry on being a chef!” exclaims Masego as she carefully pours out a fixed measurement of molten brown fudge onto the lightbox. It spreads into a perfect circle for measuring the diameter, already less than the figures the previous chocolate fudges have given.

One of the group’s white fudge batches reaches 114°C, ready to measure and mould. (Photo: Marie-Lais Emond)

I immediately think of Big Food snapping up these perfectly qualified food scientists. I’m not sure I like the idea much but does it necessarily have to be with negative food consequences, I wonder.

Then I remember Dagutat, the biolab company run by two women scientists, one a biologist. In combination they’re not that different in qualification from these eventual graduates. The labs there are not far from here, in Pretoria as well. I met Helga Dagutatand Nita Breytenbachwhen I was writing about the black and white truffles they produce under the Mustérion side of their business.

That side is tiny compared with Dagutat itself, which produces natural mushroom or mycelium fertilisers, so that farmers who need to export their crops from South Africa aren’t disqualified from doing so because they may be fertilising chemically as is often still practised here when not censored by eco-preferences.

In addition to fertilisers, using the same natural products, the women produce natural mycelium-antidotes to all common rots and mite problems in agriculture, instead of the farmers’ spraying crops with the commonly used high-chemical insecticides, now frowned on by importers of South African goods like maize and wine grapes. I know McCain uses the Dagutat women’s services in Limpopo for growing their potatoes safely and nutritionally, for instance. Any big food producer could, as could any small producer. It’s something that could be seen as using food science on the benign side of Big Food.

As attitudes to our food changes, food science may start to swing from Monsanto to more regenerative and responsible food farming. It’s likely that food scientists can play roles there.

Breaking up Cadbury’s Bourneville chocolate into the bowls of sugar, milk and butter, Leila says, “We needn’t even have been testing chocolate. It turns out what we chose was a hard one because chocolate is actually very finicky and as scientists we have to be very precise. We decided in first year already to do it.” This project investigates various chocolates with different compositions and their effect on baking or producing food items such as chocolate fondant or fudge.

Leila Schultz brushing sugar crystals from a milk choc fudge pot. (Photo: Marie-Lais Emond)

Their first year included microbiology, chemistry and stats. Over the in-between years and along with scientific research and experiments, these four women have even covered subjects like merchandising, marketing and general management in the food industry. It seems like a huge cross section to me. I notice they even change the colour of their chef aprons and uniforms on different subject days, while each year they’re different too. On recipe development days it’s blue.

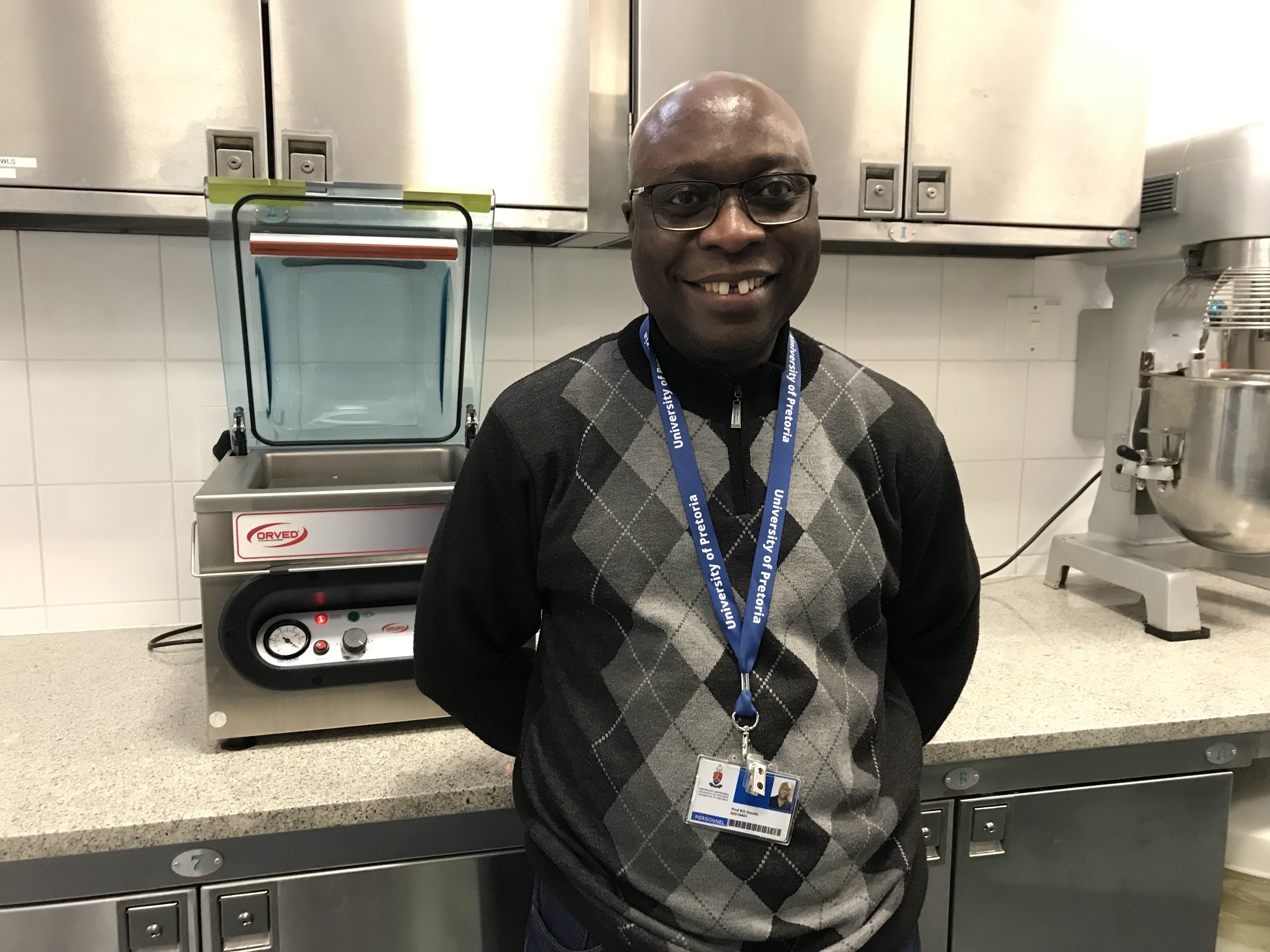

Professor Gyebi Duodu pops into the lab. He’s on the Consumer Food Sciences side, so keen to see how the sciences are being advanced right here, as he says with a twinkle.

Professor Duodu, ‘Keen to see how the sciences are being advanced today!’ (Photo: Marie-Lais Emond)

The fudges in their tins are building up, three each of the white and milk chocolates, Cadbury’s Bourneville fudge mixture soon filling all three pans. What’s next, being mixed, measured, whisked and poured, the viscosity markedly lower than all the fudge mixtures that preceded it, is from Lindt Swiss Bittersweet, the darkest of all.

I get myself some more coffee from the machine, good coffee too. Maybe it goes with the territory. When I get the milk, I’m careful about not using the stuff that’s being used in today’s experiments.

“The other milk for coffee is in the jug on that same shelf,” says Hlengi. That’s all there is there but on the glass door is written, Sous Vide Pork Do Not Touch.

At lunch time I learn from the office staff of Dr Hennie Fisher, who are offering to fetch me a takeaway lunch, that this campus is blessed to have Lucky Bread, the wonderful food people I came across at the Linden market recently, the one that wasn’t in Linden. There’s also a Vida e Caffѐ here. Knowing everything is probably marvellous and privately holding an image of their excellent pain au chocolat in my mind, I ask the woman going to get it what she’d have. She recommends a cheese and ham roll. So I’m surprised when I open the packet and find a hot egg and bacon bun. I eat it very happily and gratefully anyway.

Professor Gerrie du Rand qualified long before this particular degree but, as an Associate Professor of Consumer Food Sciences, is doing something for a major international food company. She’s come in today to pick up something from a back office because she is working on methods of eliminating all fats from their products, so no butter or oils. We wonder why, when the healthier world is turning towards good fats such as butters and olive oil. I see something in her of the thrill of accomplishing the assignment. The reason for it need not be clear but it’s a great challenge to her, something of an honour too. I wonder again about the four women around the long lab island.

As the black Lindt is readied (“It’s very different,” says Jenna), Hennie Fisher comes in to see how the timetable looks. There are more tests coming to the set fudges regarding density. He prods the dud caramelised ‘white’ fudge. “And this?”

Fisher, known as Gauteng’s “chef maker”, heads this department. It was he who also first introduced me to Future Africa on another UP campus. There I realised that universities whose disciplines meld with each other’s, and work concurrently or at least combine and share knowledge, are very much the academic future wonders. It is still something surprisingly rare today.

I watch the busy young women and wonder again about the future of food, food learning and food learners. I think back to Feran Adrià’s ElBulli Lab, which really did operate as a laboratory.

Noma’s René Redzepi started the Nordic Food Lab in Copenhagen to keep food alive, lively and very new, albeit quite natural. Jozi’s own Urbanologi, as it was under Angelo Scirocco and then Jack Coetzee, had its fermentation lab shared with Mad Giant. Those are and were just some of the science chefs we know of.

Is food development that far off, I wonder wistfully. One of the two “guinea pig” scientist chefs works in Austria developing sauces and soups. The other is doing her Masters. Food developers can often predict new flavours and know which vegetables are in “fashion”. There are others who dream big, looking at how to produce whole new, so-called ecosystems. Or are replacing sugars not just with sweeteners but with things that replace sweetness itself.

I’ll be following them excitedly, Hlengi, Masego, Jenna and Leila, these future sci-wonders of our ever-developing food world. DM/TGIFood

University of Pretoria Department of Consumer and Food Sciences, Faculty of Natural and Agricultural Science. 012 420 3780

The writer supports Nosh Food Rescue, an NGO that helps Jozi feeding schemes with food ‘rescued’ from the food chain. Please support them here.

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

Comments - Please login in order to comment.