TALE OF TWO TOXIC ACCIDENTS

Why is UPL still sitting on dioxin analysis tests 10 months after the Cornubia fire?

More than 10 months have passed since clouds of toxic chemical smoke and dust spewed over residential areas north of Durban for well over a week. Yet, the multinational UPL pesticide and agrochemicals group has still not released the full laboratory test results and health risk analysis for some of the most poisonous chemical substances thought to have been released after the 12 July arson attack on its Cornubia warehouse.

No two accidents are ever the same. Nor are the causes and consequences directly comparable.

Nevertheless, there may be some value in comparing the responses to two major chemical accidents which share several common denominators, including the release of large volumes of highly toxic chemical compounds close to residential areas.

And second — and perhaps more critically — to contrast the degree of urgency devoted to analysing and communicating the human health risks of both incidents.

The first incident happened on 10 July 1976 at a chemical plant in Seveso, Italy, owned by the Swiss-based Roche pharmaceuticals giant.

The second happened on 12 July 2021 at a chemical warehouse in Durban, leased by the Mumbai-based UPL agrochemicals giant.

Toxic smoke and dust pours from the UPL warehouse several days after the fire. It contained an estimated 4,362 tonnes of pesticides, 1,177 tonnes of combustible solids/liquids and 35 tonnes of solvents. (Photo: Supplied)

Following an explosion at the ICMESA chemical plant near Seveso, hundreds of nearby residents were exposed to very high levels of a unique chemical combustion by-product known as 2,3,7,8-Tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin (TCDD or dioxin).

Several dioxins are classified as human carcinogens and are potent endocrine disruptors which cling to fatty tissues and have a long half-life in humans.

Here are some of the most interesting points to note from Seveso, for comparison to Durban further below.

- Within nine days of the Seveso chemical explosion, Roche had collected and analysed a multitude of soil samples and swiftly alerted the Italian authorities to the very serious risks to the surrounding population due to dioxins.

- Within 15 days, the first of more than 700 residents were evacuated from their homes as a precaution. Many never went back and their homes were demolished. Women in the first trimester of pregnancy were also advised to move out until the foetus was at least three months old.

- Within three weeks, a team of Italian medical researchers started collecting hundreds of blood samples from people living close to the factory (even though there was no technology at that time to accurately measure the TCDD levels in human blood).

Writing in this historical review article about the Seveso accident and other subsequent dioxin releases, Indiana University chemistry analyst Prof Ronald Hites records that: “On 20 July, Roche notified the Italian authorities that 2378-TCDD had been found in the soil samples. This information caused a sensation in northern Italy, and the next day the ICMESA technical director and the ICMESA director of production were arrested.”

Roche also provided a preliminary map of dioxin chemical concentrations on 23 July and suggested closing the area nearest to the plant and evacuating the people living there.

By the end of July, more than a thousand 2378-TCDD measurements of soil and vegetation had been made, according to Hites.

Why dioxins are a big deal

The first evidence pointing to the serious health dangers of dioxins emerged around 125 years ago when workers in the nascent German chlorine industry began to develop liver damage and a severe form of acne that came to be known as chloracne (chlorine acne).

Visible symptoms included faces speckled with black spots as well as cysts and pustules over large parts of their bodies, including the back, genitals and earlobes.

The World Health Organization now recognises that dioxins are highly toxic and can cause reproductive and developmental problems, damage the immune system, interfere with hormones and also cause cancer.

During the 1960s, American dermatologist Dr Albert Kligman deliberately exposed prisoners to dioxins as part of a series of experiments requested by the Dow chemical company to compare the skin impacts between rabbits and humans.

Also during the 1960s, the US military sprayed large volumes of dioxin-laden Agent Orange poisons to defoliate crops and jungle vegetation over large parts of Cambodia and Vietnam.

In 2004, suspected Russian agents used TCDD to poison and disfigure former Ukrainian president Viktor Yushchenko.

More recently, evidence has emerged that dioxin exposure may cause second- and third-generation health impacts from mothers and fathers exposed during the Seveso accident.

Much of what scientists now know about the risks of dioxin exposure is the result of numerous scientific studies conducted after this accident — including the subsequent health risks to children whose parents were exposed in Seveso.

Let’s come back to Durban to interrogate the response to similar events that happened 46 years later at UPL’s brand new 14,000m2 pesticide and farm chemical warehouse at 30 Umganu Drive, Cornubia.

It is important to note that the UPL facility is a warehouse, not a chemical production plant. It did not explode due to operational failure, but was set on fire deliberately by arsonists — resulting in a massive fireball explosion and subsequent airborne emission or waterborne leakage from roughly 5,500 tonnes of agrochemicals.

According to Dr Lucian Burger, a specialist chemical engineering consultant contracted to advise UPL, it contained an estimated 4,362 tonnes of pesticides, 1,177 tonnes of combustible solids/liquids and 35 tonnes of solvents.

Apart from the known risk of dioxins being generated when pesticides are burnt, many of the poisons and products stored at Cornubia are also very likely to have contained dioxins even before they burnt.

And in the case of residual chemicals that did not burn completely, large volumes leaked into the surrounding soil and rivers when fire crews hosed down the flames with more than a million litres of water.

Evidence to support this comes from several Australian studies on residual dioxin levels in pesticides. One of these studies, led by former University of Queensland researcher Dr Caroline Gaus, showed that every single pesticide tested at random contained varying levels of dioxins. Gaus explained the risks further in this 13-minute video clip interview with Australia’s Channel 4, below.

Due to the known health risks of these unique chemical compounds, Our Burning Planet sent a formal request to UPL on 28 September asking whether it had collected dioxin samples in the air, water, soil or other media near Cornubia — and if so, what measurements had been recorded.

The company fobbed us off with this response: “Continuous air monitoring, soil and water sampling has been taking place, and is ongoing. The test results form part of the weekly and monthly reports to the authorities.”

On 13 April, 4 May and 11 May we sent further queries to UPL. Finally, more than 10 months after the fire, it has emerged that:

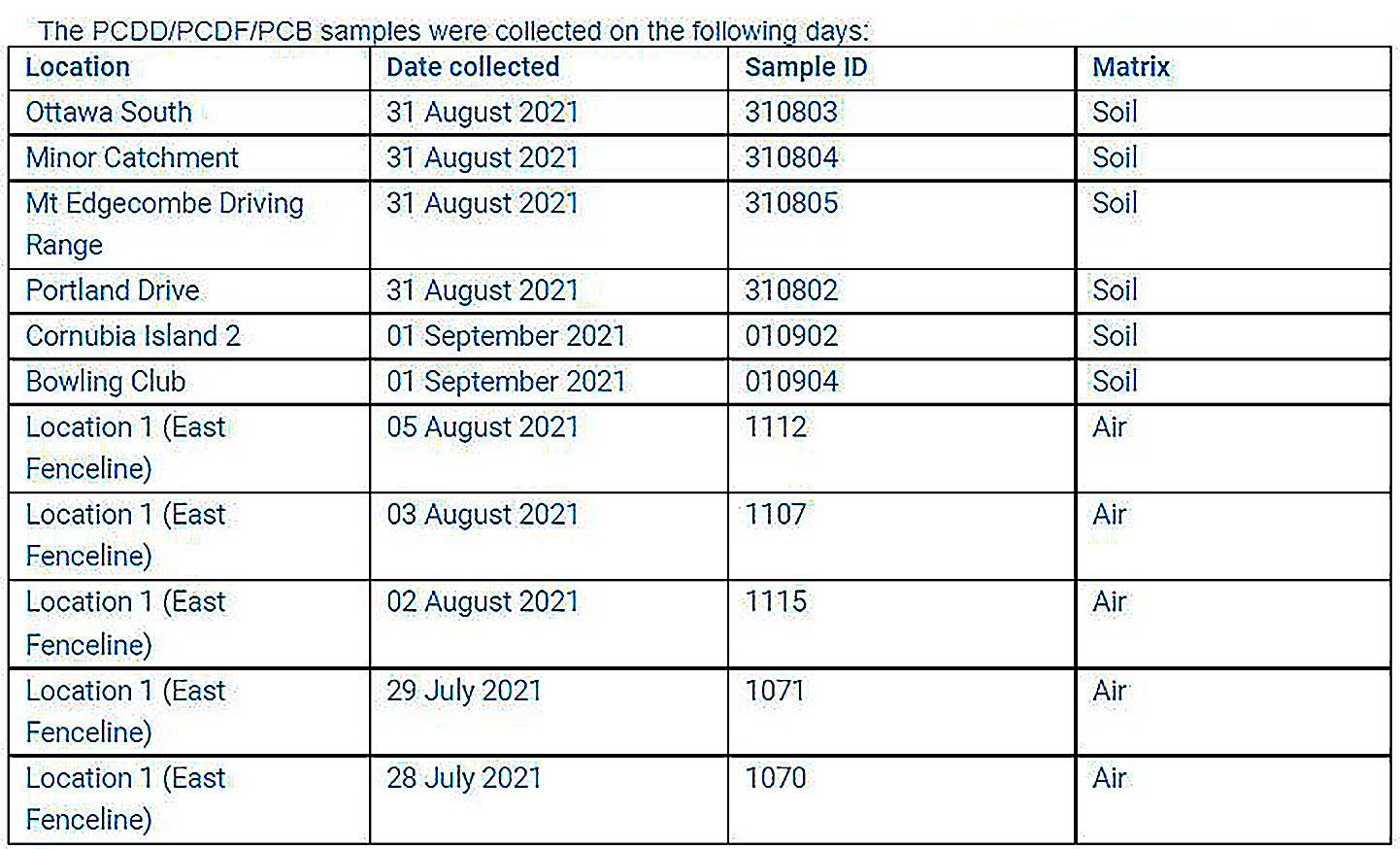

- Only five air samples from one location and six soil samples from different locations have been analysed specifically for PCDD/PCDF (dioxins and furans) over this time, although well in excess of 3,500 other samples have been collected and analysed for (non-dioxin) chemicals and metals.

- Unlike Seveso, where hundreds of blood samples were collected within three weeks, not one sample of human blood or tissue (or animal, seafood or plant sample) has been analysed specifically for dioxins.

- Not one surface water, groundwater or seawater sample has been analysed specifically for PCDD/F dioxins.

- UPL says it “submitted” a report on 18 February 2022 that contained some dioxin analysis results for air and soil — but the full laboratory-accredited reports on dioxin levels in each sample still do not appear to have been sent to the authorities.

- UPL says the five air samples directly next to the warehouse showed no detectable levels of dioxins and that the six soil samples showed such low levels of dioxins that “all indications are that the levels of PCDD/F, PAH and PCB associated with the fire do not warrant further testing”.

In other words, UPL and its consultants seem to have pretty much written off dioxins as a significant threat to people or the environment on the basis of a very limited number of analysed samples.

But if the measured dioxin results are so low and insignificant, why not release the full lab results as requested?

In response to our request, UPL demurred and stated: “Raw data always requires interpretation in order to provide meaningful information.”

Considering that the results of the Seveso dioxin tests were red-flagged and presented to the Italian authorities within a matter of days, we asked UPL to explain the reasons why it has taken so long to analyse and release such a limited number of Cornubia dioxin samples.

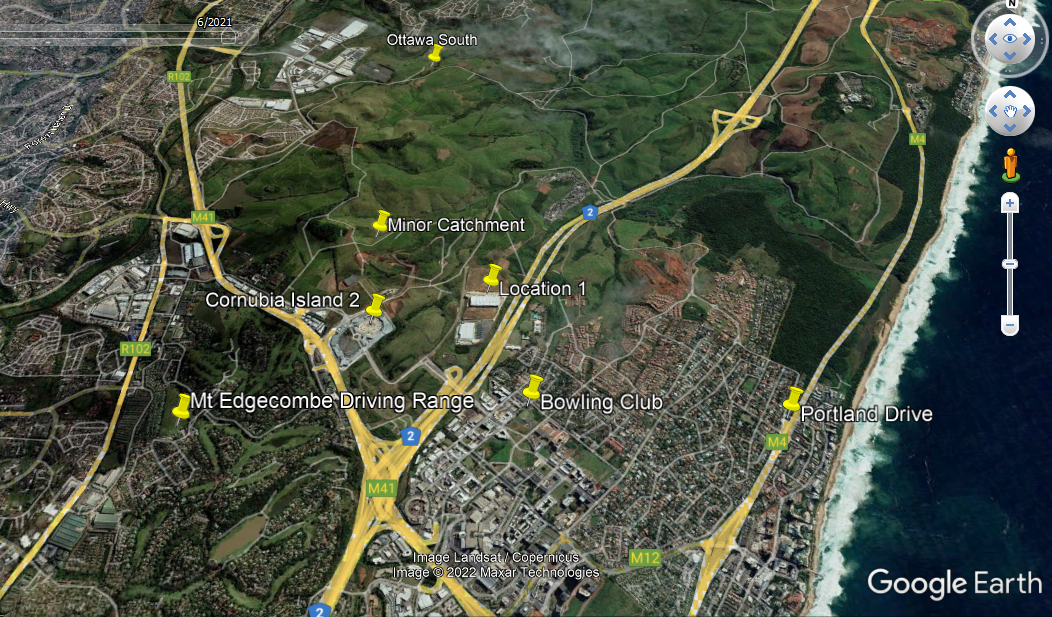

An aerial view of the six sites where soil samples were collected and submitted for dioxin analysis. Soil samples collected from the nearby Blackburn village, which is predominantly downwind from the warehouse, do not appear to have been analysed for dioxin. Five air samples (all from a single point on the perimeter fence of the UPL warehouse (Location 1) were also submitted for analysis. (Image: Supplied)

In response, UPL said that Skyside (one of the company’s specialist environmental consultants) had “struggled to find a laboratory with appropriate accreditation that could offer the range of analyses we wanted”.

“This was particularly true for the air samples that were collected during the early days of the fire and aftermath… It submitted samples for polyaromatic hydrocarbon (PAH) as it progressed and held library samples for subsequent analysis.

“Skyside was advised and agreed it was sensible to await the air dispersion model projections and the public complaints data before starting the analysis.

“A subset of the samples representative of the public concerns and dispersion pattern was selected for initial analysis and a full set of samples was dispatched to SGS Belgium’s Antwerp laboratory for comprehensive analysis on 22 September 2021.

“The analysis and reporting of the samples was unfortunately delayed by SGS Belgium’s Antwerp laboratory, despite Skyside being at pains to express the urgency of these results.

“The report containing the full set of PCDD/PCB/PCDF’s from SGS Belgium’s Antwerp laboratory was received on 23 December 2021 (during Skyside’s annual shutdown period). On receipt the overall monitoring report was updated and submitted on 18 February 2022.”

A table provided by UPL showing the sample sites and dates for currently analysed dioxin samples.

It is noteworthy that the preparation and analysis of dioxin samples, while complex and expensive, can normally be completed within less than a week, according to the US-based Sigma-Aldrich chemical analysis company.

So, despite the sense of urgency suggested by UPL and its consultants, not a single sample was submitted for dioxin analysis until two months after the fire. And when those results finally arrived, they were only “submitted” seven months after the fire.

The UPL responses are not explicit on whether these results were submitted to the government’s oversight team or to UPL’s appointed toxicology consultants for further interpretation.

The government was also not able to provide any dioxin lab results to us. Nor does it seem to be aware of the suggestion by UPL that dioxins “do not warrant further testing”.

We requested information about the measured results of any dioxin samples via the national and provincial departments of environmental affairs and the Ethekwini municipality.

In a joint response, they said: “(The) final report on the PCDF/PCDD is still outstanding and is currently being compiled by the appointed specialists… After results are received, further analysis of the results is required. Once the report is ready, it will be made available.”

While UPL has not provided the full lab certificates to Our Burning Planet, it said that all five soil samples for persistent organic pollutants (POPs) showed concentrations below 2 ng TEQ/kg and that this “took the undetected dioxins & furans into account”.

These responses introduce some uncertainty on whether the soil samples were analysed specifically for dioxins, or based on broader extrapolation from POPs analysis.

UPL says it also analysed a further six samples for polychlorinated biphenyls and 76 samples for polynuclear aromatic hydrocarbons, but the very limited number of PCDD/F (dioxin) samples analysed so far raises questions as to whether this was a sufficiently robust sample size to rule out further tests, considering that the Cornubia warehouse is surrounded by several densely populated residential areas with diverse topography.

A Human Health Risk Assessment situation report by Apex environmental consultants suggests that it will be necessary to study the health profile of at least three groups — around 200 people closely involved in the emergency response (including firefighters, toxic clean-up, security and demolition crews), along with 7,000 residents of the nearby Blackburn informal settlement and up to 100,000 residents in neighbouring areas such as Prestondale, Woodlands, Herrwood Park, Umhlanga, Mount Edgecombe, Somerset Park, Sunningdale and La Lucia.

Toxic chemical clean-up crews at work in a visibly polluted stream near Cornubia (Photo: Supplied)

There are also questions on why UPL (or the government) has yet to analyse human, animal, water and plant samples for dioxins, considering that large volumes of toxic chemicals were also flushed out of the warehouse when fire crews hosed down the fire.

In response, UPL suggested that no “classified” organochlorine pesticides were present in the warehouse and that such pesticides were forbidden in South Africa — apart from DDT used by the Department of Health to control malaria mosquitoes.

“That having been said, and as noted in the Air Impact Assessment (AIR), certain of the pesticide formulations (at Cornubia) contained chlorine. These were included in the calculations for hydrogen chloride with the possible generation of dioxins. The predicted emissions are presented in the AIR.”

So, 10 months down the line, there is still no clarity on the human health risks posed — not just from dioxins alone, but from a veritable cocktail of other toxic chemicals.

Further extensive sample analysis may well demonstrate that dioxin levels around Cornubia are indeed “insignificant” from a human health perspective.

Hypothetically, however, if the measured dioxin results were sky high, neither the public nor the health authorities would be any the wiser — because the first (limited) dioxin test results were only submitted for toxicology interpretation more than seven months after the fire.

Little wonder, then, that civil society groups have voiced concerns on limited access to information and the need for second opinion scientific peer review via the Cornubia Multi-Stakeholder Forum, which UPL has “hesitated” to recognise. DM/OBP

[hearken id=”daily-maverick/9419″]

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

If I understand this correctly, UPL is either investigating themselves, or directing the investigation into the future risk in the aftermath of the fire. Pretty convenient.