UNCOMFORTABLY NUMB: ANALYSIS

Our antidepressants in the water are making the fish come undone

An item appeared in the international news media last Friday that was next-level apocalyptic. More than a hundred fish species off the Florida coast had been found with heavy traces of human pharmaceuticals in their blood, most of which were antidepressants. The fish, of course, were exhibiting some strange and dangerous behaviours. Question is, will there be a wake-up call in here for us?

- ‘It is not half so important to know as to feel.’ — Rachel Carson.

It’s a cliché these days to observe that the news can be a hazard to our collective mental health. The prospects for the ignition of World War 3 in Eastern Europe, new variants and outbreaks of a pandemic that we thought was over, increasingly shrill warnings of the collapse of our biomes and the attendant unravelling of modern civilisation — none of these stories, which are now standard fare across most of our major media platforms, encourage what is colloquially referred to as “balance”. Still, through our enforced numbness, some stories shout louder at us than others.

One such story was buried deep below the headlines in The Guardian last Friday, 29 April.

“Fish on drugs,” the item stated, before explaining that “a cocktail of medications” appears to be “contaminating [the] ocean food chain”.

Really?

Yup, really.

A click-through to the story proper (and who, in their daily doom-scrolling, could refuse the dystopian promise of such a lead?) revealed that a three-year study had confirmed “widespread traces of a total of 58 medications including heart drugs, opioids, antidepressants and antifungals in increasingly rare bonefish and their prey”.

As it turns out, with nearly five billion medications prescribed annually in the United States alone — and the average American on a regimen of 12 prescriptions per year — human wastewater has been playing havoc with fish species off the coast of Florida.

The full report, commissioned by the state’s Bonefish and Tarpon Trust, concluded that more than half of the bonefish sampled had drugs in them at levels “above which we expect negative effects”.

Apparently, one of the bonefish tested positive for 17 pharmaceuticals, “eight of them antidepressants that were up to 300 times above the human therapeutic level”.

And while the study had found an average of 11 pharmaceuticals in all of the 125 fish species upon which the bonefish feed, the truly alarming part came when The Guardian zoned out into the broader context.

“In 2013,” noted the reporter, “scientists from Umea University in Sweden… found that wild perch were less fearful and more antisocial when exposed to anti-anxiety medications, which could affect feeding and breeding.

“A 2016 study by the same university found salmon exposed to this medication swam faster and had riskier behaviour.

“Crayfishes’ exposure to antidepressants has been linked to altered behaviour, increasing their boldness and the time they spent foraging, potentially making them more vulnerable to predators.”

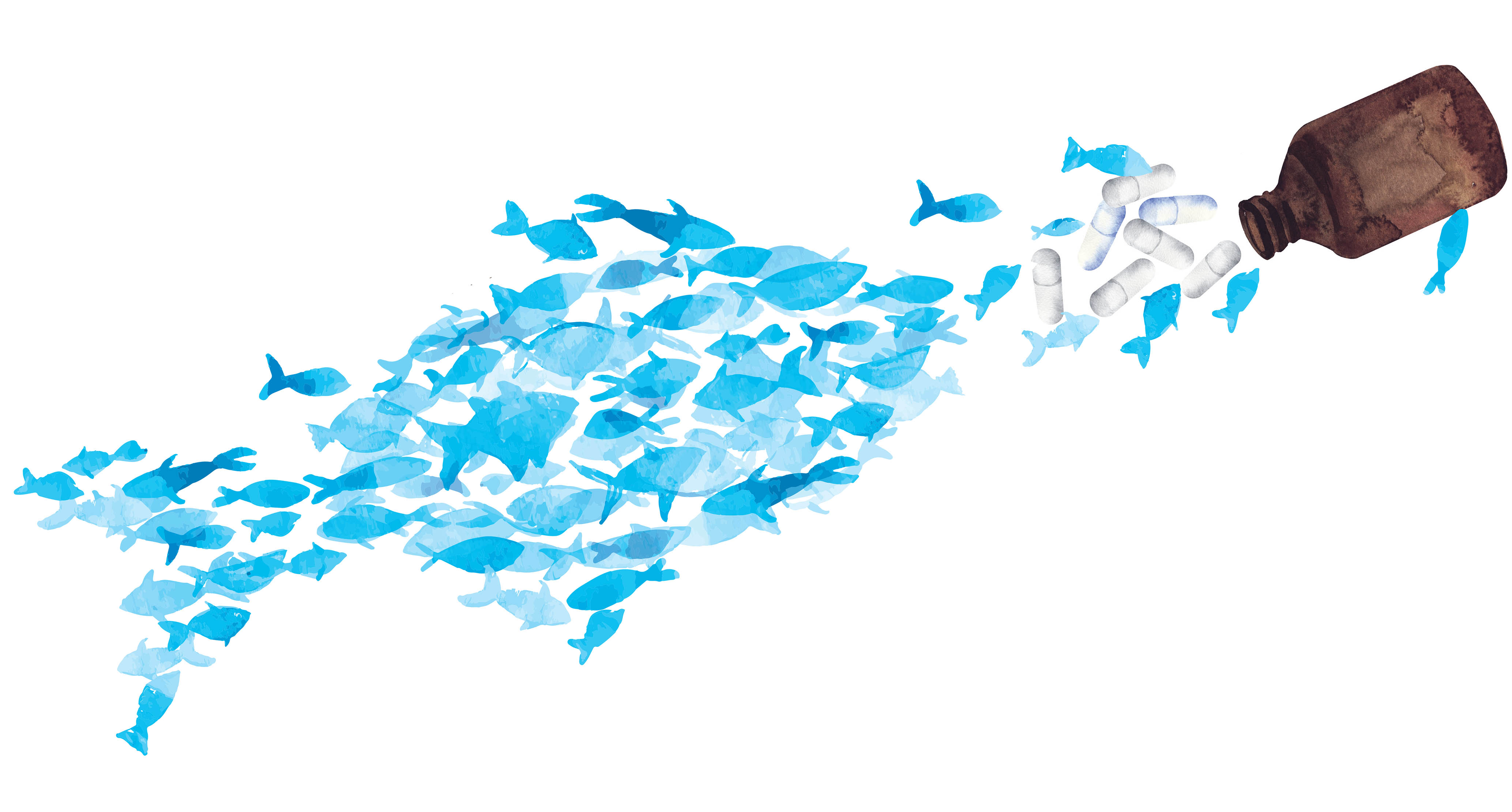

So this, it seems likely, is another way in which we are killing our precious marine world. Aside from the anthropogenic climate change that is directly implicated in the mass coral bleaching of the Great Barrier Reef, the vast international fishing fleets that are eradicating the Pacific’s bluefin tuna and the deep-sea mining that threatens to wipe out entire oceanic ecosystems, we appear to be inducing chemical imbalances in the world’s underwater inhabitants.

How, then, should we continue to attend to our own imbalances, whether we choose to engage with the daily news or not?

For a number of years, scientists across a range of disciplines have been trying to figure out why the graphs on certain mental disorders have continued to trend flat, when the available pharmaceutical treatments have never been so plentiful. (Photo: heart.org/Wikipedia)

At the risk of venturing into the esoteric, what the “fish on drugs” story demonstrates, before anything, is that nothing is separate. Our external environments, as human beings in the first apocalyptic stirrings of the Anthropocene, are a sublimely accurate reflection of our collective internal environments.

The truth, if we care to look beyond ourselves, if our personal anxieties and griefs and despairs are to be placed within the framework of the most profound planetary laws — for instance, what is in one is in the whole — is that our medications aren’t working for us.

Because, as scary as this truth may be, it’s not just the fish off the Florida coast (and God-alone-knows where else) that are being short-changed of their evolutionary safeguards — it’s apparently our own species too.

For a number of years, scientists across a range of disciplines have been trying to figure out why the graphs on certain mental disorders have continued to trend flat, when the available pharmaceutical treatments have never been so plentiful.

We all seem to know that the pandemic triggered a sharp spike in the data, with the World Health Organization confirming that the global prevalence of anxiety and depression had risen a staggering 25% in the first year, but what’s less well-known is that even before Covid hit, we were scratching our heads in wonder at the stats.

In November 2019, in a peer-reviewed paper published in the American Journal of Biological Anthropology that had been funded by a grant from the US’ National Science Foundation, researchers Kristen Syme and Edward Hagen submitted their findings under the following header: “Mental health is biological health: Why tackling ‘diseases of the mind’ is an imperative for biological anthropology in the 21st century.”

In the first paragraph of the introduction, with all the necessary citations, they stated the case bluntly: “During the 20th century, the biomedical sciences rapidly reduced the global burden of infectious disease, leading to dramatic increases in life expectancy (Murray et al., 2015). In the 21st century, chronic, non-infectious diseases have emerged as major contributors to the global disease burden (Benziger, Roth, & Moran, 2016), with mental disorders playing a substantial role (Whiteford et al., 2013).

“The causes of most mental disorders, however, remain a mystery, and there has been little progress in reducing the prevalence of any of them.”

From within an evolutionary framework — which is to say, the framework of ancestral human biology as opposed to contemporary biomedical psychiatry — what Syme and Hagen were arguing for was an entirely new lens on mental disorders.

It wasn’t their intention, as it certainly isn’t the intention of the author of this piece, to suggest that all psychiatric drugs should be outlawed, or even that many of the drugs haven’t together saved millions of lives (which they clearly and obviously have), but it was their stated mission to shift our gaze to the bigger picture.

For Syme and Hagen, who set out first and foremost to convince their peers in the field of biological anthropology that a) there was “a genuine and widely recognised theoretical crisis in mental health research” and b) that these peers were perfectly placed to fill in the gaps, the vast perspective of evolutionary time offered the most sensible way through.

In the second part of their paper, after laying out the problem in painstaking detail, they suggested a “provisional evolutionary schema for conceptualising mental disorders” that sliced the subject matter into four groups.

This schema, as noted, “identifies one group as relatively rare disorders of development that are probably caused by genetic variants, one widespread group that comprises aversive but probably adaptive responses to adversity and therefore are likely not disorders at all, one group that is probably due to senescence, and one group that might be caused by mismatches between ancestral and modern environments”.

Without getting further into the terminological weeds, it was the second group that, for a brief moment, elevated their research into the media’s mainstream.

Under the title, “Researchers Doubt that Certain Mental Disorders are Disorders At All,” Forbes magazine reported that Syme and Hagen had provided compelling evidence “to think of depression or PTSD as responses to adversity rather than chemical imbalances”.

Given that medical science has never been able to prove that anxiety, post-traumatic stress or depression are inherited conditions, the report noted, there appeared to be a distinct collective upside to this new evolutionary lens — “adversity is something we can overcome, whereas a mental disorder is something to be managed”.

And in terms of the placebo effect, it turned out, this conclusion wasn’t nearly as radical as the casual observer may have thought.

In November 2018, the New York Times Magazine ran a front page feature entitled, “What if The Placebo Effect Isn’t a Trick?” For around 5,000 carefully crafted and referenced words, the author made the case, based on a quarter-century of hard evidence, that you could give patients a sugar pill, and those patients — “especially if they have one of the chronic, stress-related conditions that register the strongest placebo effects and if the treatment is delivered by someone in whom they have confidence” — would get better.

What were some examples of these so-called conditions? According to the New York Times, the labels included depression and PTSD.

But before we get to suggesting what this all might mean for our over-prescribed fish, it’s important to note that there has lately been a great deal of hand-wringing within the halls of psychiatry itself.

In late March 2022, The Nation magazine weighed in with the investigative feature, “Breaking Off My Chemical Romance”, arguing that “we deserve a fuller picture of both the benefits and dangers of antidepressants.” The feature zoned in on one of the most “hardcore” forms of antidepressants, known in the trade as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, or SSRIs.

What if we realised that numbing ourselves wasn’t working; not for us and not for the fish?

Expanding from the individual case of an Australian psychiatry student who had been diagnosed with narcolepsy a few months after signing up for an SSRI — and who had later been prescribed both Ritalin and Ambien to help him stay focused during the day and fall asleep at night — the article went on to detail how the attempt to quit such drug cocktails had “basically ruined” countless thousands of lives.

“The theory that antidepressants correct a chemical imbalance of neurotransmitters like serotonin and norepinephrine is not a proven fact,” The Nation noted.

“Their basic functioning has not been definitively established. The story we all know is more marketing than science. And the incentive to find out whether they are indeed the best way to treat depression does not exist.

“In a world where so much scientific research is conducted by pharmaceutical companies and the entities they back, if drugs are making a profit, there’s little reason to question them.”

Still, as implied, the article quoted a solid cross-section of working psychiatrists who had recently come up with a lot of reasons to question them, not least of which was the fact that “several of the antidepressants still fell below the threshold of clinically significant improvement over a placebo”.

Importantly, and to reaffirm what was stated above, the point of this op-ed is not to argue that all psychiatric drugs are “bad”.

As The Nation made clear: “The strongest evidence for the beneficial effects of antidepressants applies to people with the most severe depression.”

The point, rather, from a writer who has fought his own battles with these drugs, is that psychiatrists — by their own overworked and overburdened admission — find it too easy to prescribe the drugs in even the mildest of cases, simply because the pressure from the pharmaceutical industry is too strong and entrenched.

So now we have oceans where fish breeding and feeding patterns, established over tens of millions of years, are hopelessly out of whack.

To ingest the “hope” back in, it seems, at least in this one emerging corner of our horrifying planetary predicament, would require recasting the dominant narrative into a form more in tune with the latest scientific research. And that, in turn, would require removing the label of “mental disorder” and replacing it with “adaptive response to trauma”.

In the context of the daily news headlines, how much of a stretch would that be? What if we chose, individually and collectively, to first notice the effect we were having on our fragile natural world — then to own it, then to imbibe it?

What if we realised that numbing ourselves wasn’t working; not for us and not for the fish?

What if we finally got that nothing had ever been separate?

What if we decided tomorrow morning to turn around and face the trauma — because that was the only way that it could, and perhaps would, be overcome? DM/OBP

[hearken id=”daily-maverick/9419″]

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

Excellent insights, thank you.

If only it was more affordable/more accessible to receive treatment from a psychologist.

Our preference for the seemingly easier option makes the “daily pill to solve those emotional problems” the preferred treatment option over the hard work of confronting those emotional problems with the help of a professional over a number of weeks.

From a financial perspective psychotherapy in private costs a lot of money (~R1000/hour session), and most medical aids do not cover a lot of sessions (or use the savings pool). Compare this to less than R500 for 1 month’s SSRIs. On the surface pills seem cheaper, whether in private or in government health. But I’ve long wondered if our propensity to treat the symptom (like a low mood with an SSRI) rather than the trauma or thought patterns causing that low mood (with psychotherapy), is part of why the rates stay constant.