BOOK EXCERPT

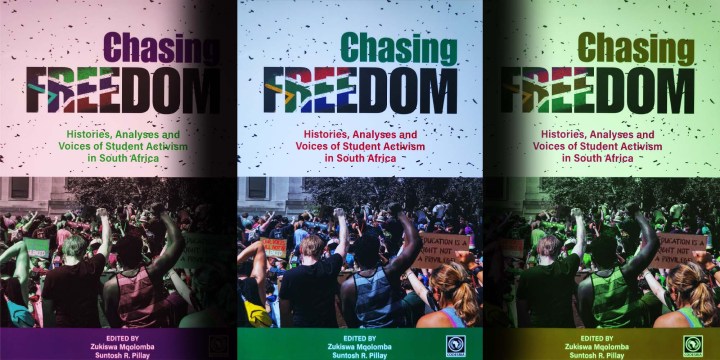

Chasing Freedom: Histories, Analyses and Voices of Student Activism in South Africa

In this excerpt from Chasing Freedom, Itumeleng Mafatshe reflects on the making of the ANC Youth League and its historical exclusion of women. Chasing Freedom is edited by Zukiswa Mqolomba and Suntosh R Pillay, and is published by Codesria.

The story of the African National Congress Youth League (ANCYL) began at a time when in-depth engagements sought to define the progression of self-determination for black people in South Africa.

Growing dissatisfaction with the ANC leadership in its response to white minority leadership in the country provided the institutional context within which the ANCYL was formed in 1944. The significance of the formation of the ANCYL lay in its desire to radicalise the ANC in relation to its approach to African people’s oppression.

In the formation of the ANCYL, there was, however, no effort made to include African women – or even conceptualise their status as the group oppressed most by white supremacy and patriarchy.

Historical research shows that the ANCYL prioritised a nationalist discourse which was void of a critique of nationalism as an ideology that ignored women and disregarded the opportunity to align the racial struggle with that of women.

The priority for the ANCYL was to challenge the ANC’s conservatism on questions pertaining to race.

The ANCYL envisioned an ANC that was able to fundamentally change the conditions of black people, and not one that wanted reform to the system that could be established only by the inclusion of black, elite men.

The younger people in the ANC had become frustrated with the party’s tone of pleading, requesting and praying to the government for change.

Their commitment to a radical version of African nationalism was founded upon their view of the ANC as “the symbol and embodiment of the Africans’ will to present a united national front against all forms of oppression” (ANCYL manifesto 1944).

The strategy of ANCYL activists was to ensure that the leadership of the ANC was sympathetic to its programme; this required that ANCYL leaders infiltrate the leadership positions in the ANC to influence resolutions and programmes from within.

Although the posture of the ANCYL was radical, its radicalism remained within the confines of a male-centred understanding of what activism was and should be.

The ANCYL galvanised young people to confront segregation in the country at a time when SA was undergoing major political and economic development, with industrialisation and urbanisation being at their peak.

The period between the 1940s and 1980s was marred by chaos and unrest, alongside high levels of unemployment and crime, especially in African townships.

Following successful deliberations between the young radicals and their parent body, the ANCYL was launched in March 1944 at the Bantu Social Centre in Johannesburg under the theme, “Africa’s cause must triumph” (ANCYL manifesto 1944).

Central to their programme was the struggle for African development, progress and national liberation without influence or collaboration with the white oppressive regime.

The ANCYL sought to create a disciplined, united and consolidated youth from which African leaders of the future would come. The programme of the ANCYL, as per its manifesto, included more radical types of activism as seen through the Defiance Campaign of the 1950s which made the country under the leadership of the National Party ungovernable.

The ANCYL was officially founded on 2 April 1944 under the leadership of Anton Lembede, Ashby Mda, Walter Sisulu, Oliver Tambo and Nelson Mandela, among others. Similar to the ANC, the youth league was led by a cohort of young educated males from the ranks of the elite in the ANC. At its inception, it was male dominated, and where women were present, they were not recognised as key players in the organisation.

The ANCYL saw recruitment as a necessary means to the development of a mass organisation that would numerically and ideologically challenge the conservative ANC.

The limitation here, however, was the inability of the then elite youth league membership to engage with and consequently mobilise the uneducated working class and peasantry. This resulted in recruitment to the ANCYL being mainly from within their spaces of familiarity, such as high schools, colleges and professional associations.

This approach systematically excluded women from recruitment into the ANCYL, as most women existed mainly outside of these spaces that served as the base for its recruitment. As a result of the systemic exclusion of women in ANCYL activism, issues that underpinned youth league politics were gendered and predominantly represented the male voice.

The specific gendered needs of women were overlooked mainly because of the prioritisation of race politics within the organisation.

The banning of the ANC and other liberation movements in the country created a gap for ANCYL activists, but also an opportunity for grassroots politics to be infused with those of the elitist ANCYL at the time.

In the absence of the ANCYL, the South African Youth Congress (Sayco) and other organisations, such as the Congress of South African Students (Cosas), played an important role in conscientising youths in townships.

Cosas went beyond its scope as a students’ organisation and became a political home for young people, including those who had completed high school. Cosas accommodated many youths outside of high schools whose activism in the organisation sharpened their understanding of the society they lived in, and provided a space for activism to thrive after their schooling.

In the early 1980s, Cosas engaged in broader societal issues, thus shifting its focus from addressing schooling challenges in the townships. In understanding the perceptions of gender within the ANCYL, it is necessary that we consider the influence of other formations, as well as acknowledge that the revival of Sayco was to a great extent an outcome of Cosas’ involvement.

This birthed the establishment of a youth congress which would focus on broader societal issues, allowing Cosas room to continue with its programme of advancing school-going students’ concerns.

The youth congresses were mainly African nationalist in their ideological perspective and served as a home for young people at a time where both their political identities and their lives as black youth in a racially oppressive country were marred by confusion and uncertainty.

The Cape Town Youth Congress (Cayco), Soweto Youth Congress (Soyco) and the Port Elizabeth Youth Congress (Peyco) were among the first of these congresses, followed by many others throughout the country.

In their drive to address social issues, particularly those affecting young people, the youth congresses evoked the spirit of radicalism that inspired the establishment of the ANCYL in the 1940s.

The activities of Sayco in the mid-1980s shaped the emergence of a subculture among politically active black youth which influenced political activism and the perceptions of those who were affiliated to the youth congresses around the country.

The youth congresses like Cosas were closely affiliated with the United Democratic Front (UDF), which led to a successful launch of Sayco in 1987 under the leadership of Peter Mokaba, who became the founding president of Sayco.

Sayco always identified itself with the ANC and the ANCYL, which the majority of its members didn’t know but had grown to love and had a sense of identification with even during the period that it was banned as an organisation.

Activism in Sayco provided room for activists to be part of the radicalism that was characteristic of the ANCYL before its banning. Although this radicalism was important for the politics in the country at the time, because of the influence of the ANCYL and its discourse, the radicalism was still found wanting, especially where this concerned the inclusion and possibilities of invasion by young women activists.

The re-establishment of the ANC became a pending issue for the leadership of the ANC after the unbanning of the party. The ANC, realising the responsibilities that lay ahead, saw a need for a youth structure of the ANC that would bring together then existing youth formations that operated during the apartheid period in the absence of the ANC.

The formations considered for this were the South African National Students Congress, which later became the South African Students Congress (Sasco), the ANC Youth and Student Section (ANC YSS), Sayco as well as Cosas.

During negotiations, the ANC YSS and Sayco agreed to merge and form the ANCYL as we have come to know it today.

Sasco and Cosas remained within the broader Mass Democratic Movement as led by the ANC in pursuit of the National Democratic Revolution, while maintaining their independence as student organisations.

The outlook of the ANCYL since its relaunch has been shaped by influences from both the ANC YSS (a section of South African exiled students as well as other anti-apartheid activists in exile) and Sayco.

Considering the differences in outlook of the ANC YSS, which was conservative vis-à-vis the more militant Sayco, the re-establishment of the youth league was evidently characterised by contestation. The militancy and radicalism emanating from Sayco became the premise for how the politics of the ANCYL would be shaped after its relaunch.

It was only after its relaunch in the early 1990s that the ANCYL seemed to consider a different attitude towards the role of women in the organisation.

In this period, women began to rise into the upper echelons of the ANCYL, and a more decisive position on the gender question and recognition of women’s activism is reflected in the policy resolutions of the ANCYL.

Although this may be so, the challenge to fully integrate women into the discourse and politics of the ANCYL remains. DM

Itumeleng Mafatshe is a development researcher and gender specialist. This is an excerpt from her chapter in the new book Chasing Freedom: Histories, Analyses and Voices of Student Activism in South Africa, co-edited by Zukiswa Mqolomba and Suntosh R Pillay (Codesria Publishers).

Zukiswa Mqolomba is a former SRC President of the University of Cape Town, former Provincial Executive Committee member of Sasco and alumnus student leader. She is a Mandela Rhodes Scholar and Chevening scholar. She has two master’s degrees and also holds an executive leadership training certificate. Mqolomba works for the Presidency of the Republic of South Africa.

Suntosh R Pillay is a clinical psychologist and researcher in the public sector in Durban with roots in student journalism, community mobilising and mental health advocacy. He completed his master’s in Social Sciences degree at the University of KwaZulu-Natal (UKZN), and is affiliated to UKZN’s Department of Clinical Medicine.

[hearken id=”daily-maverick/9472″]

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

Comments - Please login in order to comment.