WAR IN EUROPE

From a township hospital in South Africa to the Ukraine border, an expat doctor has seen the trauma of poverty and now war

Russian forces may have been pushed from the outskirts of Kyiv, but they are pressing harder along the front in the east and south of the country. A Cape Town doctor has seen a corresponding uptick in the number of refugees and patients at the makeshift medical station where she volunteers.

Dr Natalia Novikova’s daily commute these days requires a little more creative thinking than her usual rush-hour drive to and from her doctor’s practice in Cape Town’s city centre.

On a cool, glistening spring morning on her way to the Ukraine border from her hotel in the nearby Polish town to Przemysl — now colonised by armies of NGO workers — Novikova winds her rental car through narrow rural backroads, past fields of dandelions and neat, blossoming backyard orchards.

The 40-something gynaecologist, originally from Kyiv, is here on a volunteer stint treating patients at the Medyka border crossing, which has seen an exodus of refugees since the war began.

This is her second tour to the border after a stint in mid-April — she can only leave her work and three kids for about a week at a time — and Novikova is still feeling her way around the detour that bypasses kilometre after kilometre of backed-up traffic that has ground to a total halt. These are vehicles heading towards war-torn Ukraine.

Expat doctor Natalia Novikova. (Photo: Facebook)

In the middle of last month, for the first time since the war began, the flow of people from Ukraine was reversed. Polish border authorities reported that on 16 April, 22,000 people crossed into Ukraine — nearly 3,000 more than had left at the same time.

Trailers full of sedans without number plates, headed for export to Ukraine, only add to the traffic — a sign that optimism about the future might cautiously be making its way into Ukrainian hearts. Evidence too that the urges of homo economicus remain irrepressible even in times of war, as the cars will go to buyers free of import duties, which wartime Ukraine has abolished.

There is a less upbeat take, though — the demand for new cars is also one of survival. Ukrainians are worried about being left at the mercy of public transport when the need to flee arises. It is a reminder that any renewed optimism in these rapidly changing times is likely to be ephemeral.

Russian forces may have been pushed out from the outskirts of Kyiv, but they are pressing harder along the front in the east and south of the country, and Novikova has seen a corresponding uptick in the number of refugees and patients at the makeshift medical station where she volunteers.

Traffic on the border is backed up for kilometers. (Photo: Micah Reddy)

“The first days back were shocking,” Novikova tells us. “Not just the sheer numbers, but being Ukrainian, it’s still sometimes hard to comprehend fully that this is now the reality…

“My mum is in Poland, where she doesn’t really speak the language and struggles in a foreign city, and I can’t imagine what it’s like for other people who have less.”

Burden on the elderly

The elderly have often been forced to fend for themselves. Novikova tells the story of an older Jewish woman who had to pay $21,000 to Russian soldiers to leave Mariupol — a city that has been levelled by intense shelling and a Stalingrad-like battle. The woman, overcome with grief and a sense of guilt for having made it out when so many others did not, broke down in tears the moment she crossed the border.

Novikova says that many old men, reluctant to leave their homes in the first place, have to be forced past the border by their wives and relatives.

“The old women will go to the bus right away, but then they’ll have to come and call the men and drag them off, because they say they’d rather die there where they’ve lived all their lives.”

For those who make the crossing, Novikova’s is among the first cluster of tents they pass, where a tarpaulin village has sprung up to house an army of NGO workers and volunteers from across the world.

Representatives of major international organisations and UN bodies are here, overseeing the steady flow of refugees and providing aid packages and advice to bewildered new arrivals.

Alongside the big players is a congregation of smaller NGOs — volunteers who have rushed to the border to be of whatever help they can, and charities of various sectarian shades doing their respective lords’ work. Today, however, is relatively quiet, and aid workers seem to outnumber refugees.

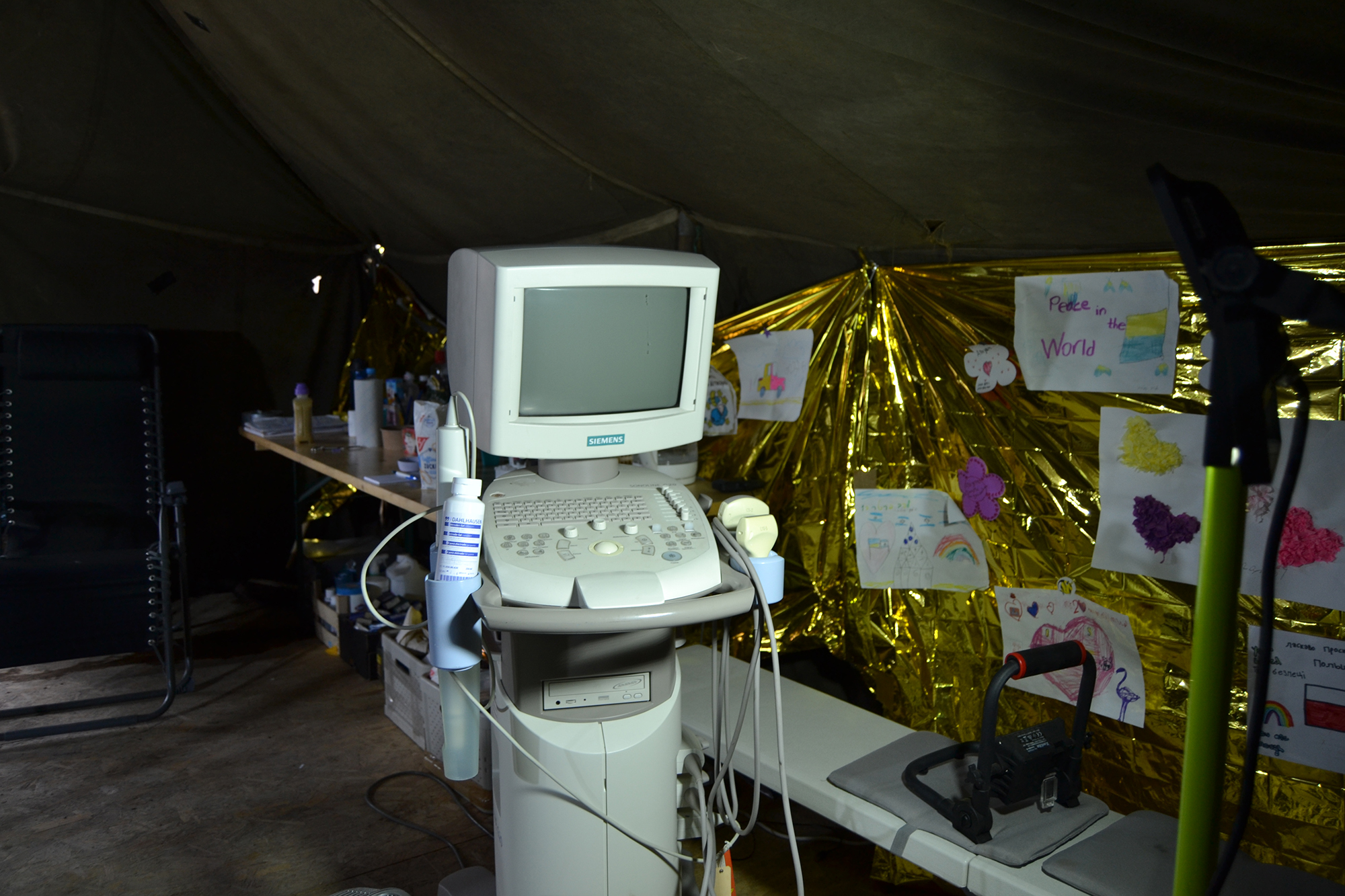

Inside the medical tent Dr Novikova uses. (Photo: Micah Reddy)

The atmosphere is almost festive, with volunteers offering passers-by free artisanal coffees and pizza slices, while someone in a giant Pokémon costume distracts war-weary children. It’s the sort of reception that refugees from other war-torn parts of the world could only desperately wish for — a total contrast to the dreary, unliveable encampments that migrants from places like Syria are forced to endure.

Human rights abuses

But the buzz in the air at the Poland-Ukraine border belies a bitter conflict that has left thousands dead. The UN believes about 12 million people have left their homes, and nearly half that number is said to have left the country amid mounting evidence of systematic human rights abuses committed by Russian troops.

Elderly and chronically ill refugees fleeing the fighting in the east arrive at the border, often after travelling epic distances across Ukraine — Europe’s second-largest country after Russia — passing through countless checkpoints and taking arduous detours to avoid shelling and flare-ups in the fighting.

For the exhausted and traumatised new arrivals, and those in need of medication, the clinic where Novikova works is the first port of call.

With other volunteer doctors, Novikova operates from a patched-up olive-green camping tent that was donated by someone from Denmark. She ended up here after an advert in a medical newsletter calling for doctors and says that the volunteering process was straightforward.

People were quick on the ground, she adds. The site for the tent was staked out by an American woman with Ukrainian links, and volunteers started working in the field clinic a week into the war, weeks before the major international aid organisations, encumbered by more bureaucratic processes, moved into the area.

Messages and drawings posted on a fence at the border. (Photo: Micah Reddy)

“There is much better infrastructure now around the border crossing and things are improving,” says Novikova. “But this war is not going to stop tomorrow.”

Inside the tent, boxes of medication are crammed haphazardly into containers, each marked accordingly — “anti-hypertensive”, “anti-ulcer” and a lucky dip of “other antibiotics” — and stashed on plastic shelves.

Medical appliances — including a newly arrived ultrasound machine, crates stuffed with first aid kits and foil blankets, a wood-fired heater and a small desk overcrowded with the detritus of the last shift — make manoeuvring tricky. A scattering of empty coffee cups is evidence of long hours at the 24-hour border post (Novikova has mostly been working night shifts).

Shortly after we arrive at the tent, an elderly woman comes in to get ointment for a shrapnel wound. She came from Bucha, Novikova tells Daily Maverick. It’s a name now tarred with a grim symbolism.

However, Novikova and her colleagues rarely encounter such cases, as trauma victims are usually treated within the country. The vast majority of patients seen here are those requiring treatment for stress-related problems and chronic health conditions.

“Hypertension, diabetes, and if they have any chronic illnesses and they stay in the line for eight or 12 hours, then everything is going to be bad… there’s anxiety, insomnia, stress,” says Novikova.

The medication the clinic requires is pooled from various donors, the Ukrainian Association of South Africa among them. The association has raised funds from among the 6,000 Ukrainians it says live in South Africa and from the broader society.

Despite all the goodwill, there are still shortages.

Novikova and her team have had to turn to South Africa to source supplies of Eltroxin, a common thyroid medication, after the facility for storing the medication in Ukraine was said to have been destroyed in the conflict and supplies elsewhere were hard to get hold of.

Novikova says that rates of thyroid conditions are common in Ukraine, and there is evidence to suggest a link to the Chernobyl nuclear disaster.

But for the most part, the patients Novikova sees need no high-end tailored treatment: “The most popular medication is simple valerian root… just to calm people down.”

South African conditions

Novikova’s experience and bedside manner have been tested by what she says are very challenging conditions in South Africa, where she has lived for more than a decade. Much of that time was spent in the Eastern Cape, where she worked in the public health sector.

“After hours, it turned into a war zone, especially at Cecilia Makiwane Hospital in Mdantsane [a township outside East London], and Frere Hospital was not all that different.

“On a Friday afternoon, for example, you’d receive ambulances with five very sick people in labour and you’d have to triage… and people with a lack of experience would have to cover.”

The worst thing, says Novikova, was the lack of access: “You’d get very serious referrals of people who should’ve been admitted long before.” On top of that, HIV was a complicating factor and rape was commonplace, sometimes involving child victims.

Mass rapes

In other words, Novikova has faced cases of extreme psychological distress. She hasn’t had to deal with rape cases at the border — this isn’t the sort of setting where victims of sexual abuse would be treated — but evidence is constantly coming to light of mass rapes committed by Russian soldiers.

The UN Special Representative on Sexual Violence in Conflict, Pramila Patten, warned that dozens of sexual violence cases under investigation “only represent the tip of the iceberg”.

Most rape cases are treated inside Ukraine, where there has been a serious demand for contraception amid disrupted supply chains.

In contrast to staunchly Catholic Poland, Ukraine, a former Soviet republic, has long had a very liberal attitude towards abortion. The Soviet big brother, Russia, under Lenin, became the first country to legalise abortion in all circumstances in 1920, before Stalin reversed the policy for many years.

“I last worked in Ukraine 20 years ago,” says Novikova, “and in my time, lots of women treated abortions as a form of contraception… in the Soviet Union abortions were very common and acceptable.”

Responding to the demand in Ukraine, Novikova’s team have sent over 150 abortion kits to contacts inside the country.

Novikova pays her own way on these volunteer missions — flights, accommodation, car rental — and says she sees her role as a modest part of something much bigger.

“It is said that every Ukrainian soldier on the frontline has to be supported by 12 other people on the ground”.

She finds comfort in being useful in a situation that otherwise can feel so hopeless.

“I’m a doctor and I speak the language, and that’s useful because the majority do not speak Ukrainian. I have a set of skills, I work for myself, and my sacrifice is nothing compared to the sacrifices of Ukrainians who don’t have homes, who lost their family members and need to find new schools for their kids and start new lives in new countries.” DM

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

Comments - Please login in order to comment.