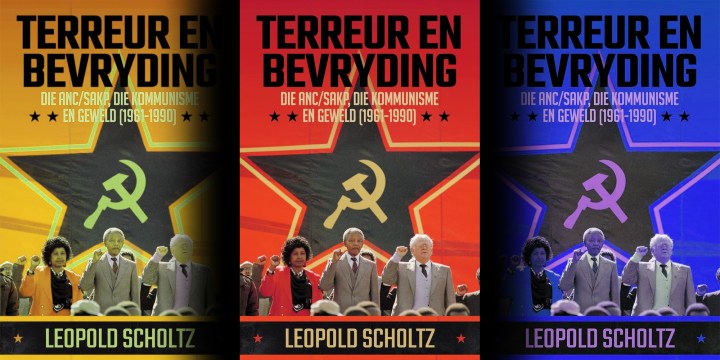

TERREUR EN BEVRYDING BOOK REVIEW

A new book by Leopold Scholtz shines a light on Russia’s history with the ANC

Journalist and historian Leopold Scholtz brings Russia’s place in South Africa’s history right to the fore and helps explain the ANC government’s puzzling stance on the Russian invasion of Ukraine. It is published by Jonathan Ball.

Today, 9 May, the world reflects on Russia’s history since World War 2 as that country celebrates Victory Day.

A new historical and political study by the journalist and historian Leopold Scholtz, Terreur en bevryding: Die ANC/SAKP, die kommunisme en geweld (1961-1990) — (Terror and Liberation: The ANC/SACP, Communism and Violence, 1961-1990) was published in March by Jonathan Ball and brings Russia’s place in South Africa’s history right to the fore.

It is a powerful and thoroughly researched work, giving an essential understanding of the ANC in exile between 1960 to 1991, and the role within it of the South African Communist Party. So too, the debilitating effect of its Russian heritage on South Africa up to today.

Issued in paperback, not only Afrikaans speakers, but anyone with a knowledge of Afrikaans should make it their business to read the book.

Scholtz’s very extensive use of quotations (most of them in English), his wide range of sources and precise references enable readers to be secure with his interpretations, even if they might wish to contest these. The book needs to be re-published in English translation and in other languages.

Examining the history of the ANC in exile, with the metamorphosis of the former Communist Party of South Africa — founded in 1921, nine years after the ANC — into what Scholtz demonstrates became the principal determinant in the ANC up to the downfall of the former Soviet Union in 1991, he gives an appreciation of the critical role of Russia in South Africa’s political culture.

No other country where the primary language of political communication is English has been more determined in its modern history by Russia (in its Soviet form), making this also a global issue — especially at the present time of Russia’s imperialist war against Ukraine.

After Zondo findings, what will ANC do about ‘Gupta Minister’ Mosebenzi Zwane?

MK budget

Scholtz states that almost the entire budget of Umkhonto weSizwe came from the Soviet Union. (“Byna die hele militêre begroting was uit die Sowjetunie afkomstig…” p.231).

The last paragraph on the back cover of the book makes the point that its major theme — the SACP’s former control over South Africa’s subsequent governing party — sums up the book’s acute relevance for today.

In translation, this paragraph reads: “Scholtz puts the spotlight on the deadly combination of severe internal intolerance and incompetence within the ANC/SACP in exile, the corruption of part of the leadership and the serious human rights abuses in the ANC’s camps in exile. He argues that what is currently happening in South Africa at all three levels of government is a continuation of a culture that had been established in exile during the years of the alliance.”

That is a very powerful claim. It cannot be wished away.

Scholtz cites a description by the former SACP activist and political prisoner, Prof Raymond Suttner, of post-1994 South Africa having a Constitution which enshrines “democratic and emancipatory values” (p.265). But as Luthando Dyasop — a veteran of Quatro, the ANC’s gulag for its own members in the war in Angola — points out in his memoir, Out of Quatro: From Exile to Exoneration (Kwela Books, 2021), an electoral system which “deprives citizens of the right to appoint and recall any elected representative who has failed them” retains a severe element of Soviet-type power-control of the kind exercised by the ANC over its members in exile (p.250).

As Scholtz points out — citing the biography by Janet Smith and Beauregard Tromp of the SACP/ANC/Umkhonto weSizwe leader Chris Hani — of the 29 members of the ANC’s National Executive Committee who were appointed at its decisive elective conference at Kabwe in Zambia in 1985, 24 were SACP members, under the party’s top-down control (p.167).

Quatro brutality

This followed the ANC’s brutal suppression the previous year of a pro-democracy movement by its troops from the 1976 generation in the war in Angola, who had demanded an end to brutality by the ANC’s security police, an end to corruption on the part of commanders, accountability of commanders in this “political army” to their troops, and to be sent to South Africa to fight. Elected representatives of this pro-democracy movement had been sent instead to Quatro, where they continued to be abused after the Kabwe Conference.

Scholtz quotes one of these Quatro prisoners, writing in 1991, that the Kabwe Conference “had no grain of democracy”. According to the writer, members of the ANC’s secret police, known as “Mbokodo” (the grindstone), had “attended the conference as journalists or catering staff. They ended up voting even though they had no mandate to do so. Later they would gloat that the purpose of the conference had been subverted” (p.164).

In his review of Terreur en bevryding, “When the ANC lost its brain” (Politicsweb, 22 April 2022), Prof Hermann Giliomee noted that Scholtz “leans in particular on the work of Irina Filatova, a Russian academic who now lives in Cape Town, and her co-author, the Moscow academic Apollon Davidson, and also that of Stephen Ellis, who taught at Leiden University, and Jan-Adriaan Stemmet of the University of the Free State”.

Superb research by professors Irina Filatova and Stephen Ellis, in particular — neither of whom was born or began their career in South Africa — established without doubt that at the time of formation of Umkhonto weSizwe in 1960-61 following the Sharpeville massacre, the pragmatist Nelson Mandela had indeed joined the SACP (illegal since 1950), and was very quickly elevated to the Central Committee.

There are almost 50 references throughout the book to writings by Stephen Ellis, who sadly died in 2015 at the age of 62. The British publisher, Hurst, has just published The Stephen Ellis Reader in paperback, with roughly 650 pages, under the title Charlatans, Spirits and Rebels in Africa, with Ellis cited on the back cover by Prof Christopher Clapham of Cambridge and former editor of the Journal of Modern African Studies as “the greatest Africanist of his generation”. A new edition of Ellis’ External Mission: The ANC in Exile, 1960-1990, is due for publication by Jonathan Ball.

Crucial research by Filatova and her colleague Prof Davidson, authors of The Hidden Thread: Russia and South Africa in the Soviet Era (Jonathan Ball, 2013), was done in the Moscow archives.

Scholtz’s book continues this tradition of exemplary research into the hidden areas of South Africa’s history of the last century.

There are two issues here relating South Africa to global conditions.

Nelson Mandela

The first is Leopold Scholtz’s examination of the facility and success of the SACP in presenting Nelson Mandela for 50 years as a celestial global icon, minus any relation to the Communist Party, and thus to Russia. South Africa’s devastating decline due to State Capture and corruption under the ANC government has since left this myth in the sky.

The second is Russia. Scholtz’s book was issued just weeks after the beginning of Vladimir Putin’s Russian invasion of its neighbour and former colony, Ukraine — a “colony” above all in terms of Stalin’s Holodomor or starvation famine, perhaps genocide, in 1932/33, which killed between 3.5 to five million Ukrainian peasants in Russia’s “breadbasket” to speed up the industrialisation of the Soviet Union.

Russia’s heavy presence within the ANC was reflected in the cowardly refusal of Cyril Ramaphosa’s government to acknowledge what would have been blindingly obvious to South Africans if Ukraine had been a society of black people.

On this day, 9 May, when Russia’s Führer — a colonel in his country’s Mbokodo in East Germany before the downfall of the Berlin Wall in 1989 — celebrates his invasion of Ukraine with a military parade in Red Square to glorify his wished-for destruction of national independence, democracy and freedom of thought in the country’s neighbour, South Africans — especially black South Africans — should consider what a war of this kind means for them.

Scholtz’s book offers the evidence to reflect and consider.

Which way, South Africans? Backwards, maybe, to a Russia-type Quatro? Or forward to the 1976 generation’s hope for a more genuine democracy? DM

[hearken id=”daily-maverick/9472″]

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

Comments - Please login in order to comment.