BOOK EXTRACT

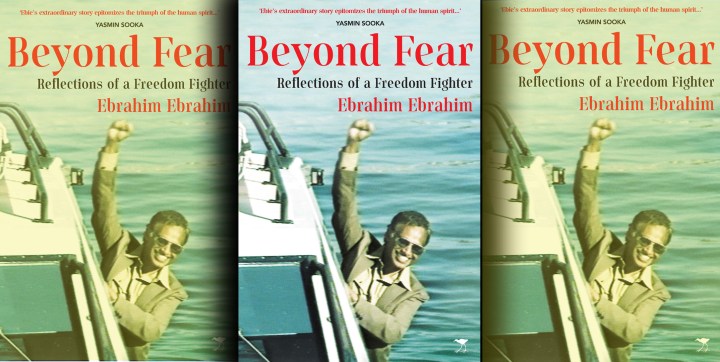

Beyond Fear – Reflections of a Freedom Fighter

A founding member of Umkhonto weSizwe, Ebrahim Ebrahim played a central role in directing the 1960s sabotage campaign. He was imprisoned on Robben Island in 1964. After his release in 1979 he operated in the ANC underground, was abducted from Swaziland in December 1986 by apartheid agents, tortured, charged with treason and sentenced to another 20 years on the island. Ebrahim died on 6 December 2021. ‘Beyond Fear’ is published by Jacana.

We political prisoners were put to work breaking stones in the blinding quarry. Here we were joined by another “span” (a group of prisoners who did hard labour), led by Andrew Masondo. Like so many of us, he was fearless and therefore a target for the warders. His group refused to obey an instruction at the quarry and were brought to the prison yard to be punished by having to pick up heavy boulders and run and throw them down into the foundations being dug for the new prison building.

Warders with batons beat the prisoners on their heads and backs as they ran. To demonstrate to us that we were not “on holiday”, the warders made us join this torture. I could scarcely carry some of the boulders.

On our first night we got pap to eat as usual. We were also given sisal mats that scratched us and offered little to no protection from the cold cement floor. If our political movement had placed some of us higher on account of our seniority, none of that mattered in terms of the living conditions within the prison system. It was common to be in an overcrowded cell, crammed with more than 80 people instead of the intended 25. I tried to stay as near as I could to comrades George Naicker, Steve Tshwete, Douglas Sparks and a few others. We were only about 10 ANC comrades there and we occupied a corner next to the entrance. Eighty unrolled mats would never have been able to fit into the cell, so every three prisoners would sleep across two mats and share their threadbare blankets. We only got beds after the mid-1970s. What made sleeping also difficult was that the prison authorities insisted on keeping the fluorescent lights shining in the cells all through the night.

Earlier that evening, we laughingly showed each other the assault marks on our bodies. We laughed because, despite the torment, we knew we were better than the warders and the government which paid them, and that their brutality and fear of us would never stop our freedom from coming. But the physical assaults on our first day in prison became routine, as did being sworn at and brought to near starvation. Many warders delighted in this entertainment. It killed the boredom of their existence. By the late 1960s, it seemed many had joined the prison service to escape conscription into the army, yet the prison system was itself militarised and all personnel had some kind of military training.

A bell rang at six in the morning and we had to get up at once or be punished. On waking, we had to fold our blankets into a pile and place them on top of the mat, which then had to be rolled up. The 61 of us had to clean ourselves in a small washroom which had only two toilets without surrounding cubicles: there was no privacy. There were three showers which we had to take turns to use. Hard, brackish, cold water spat onto us, and there was no chance of it washing the soap out of your hair.

We then had to get dressed and be ready when the warders opened the cell and shouted “Val in!” (fall in line). We had to stand in twos to be counted. Warders would be posted on either side of the doorway to hit us with their batons as we stepped out of the cell. Since we always had to leave our shoes and sandals outside in the open, we simply grabbed any two we could lay our hands on as we went out. As a result the shoes we wore all day were often of different sizes, and sometimes meant for the same foot. On the way to the prison kitchen, inmates were able to make a quick exchange.

We queued for breakfast. This consisted of a plate of soft mielie porridge and a teaspoon of brown sugar handed to us as we passed the kitchen. We would then collect a metal mug to scoop black coffee out of a huge pot, and squat in rows to eat. Seagulls would hover, motionless, above us throughout the meal, and their droppings sometimes fell into our food. We were given wooden spoons when we arrived, and after eating, we had to lick the spoon and put it into our pocket. That spoon would remain with us at all times.

Then would come the call for “hospital”. A medical warder would call out “fuba”, meaning “chest”. All those who had a cold, cough or problems with their respiratory system would stand in a queue. The warder would not enquire as to your ailment but simply proceed to administer to everyone in the queue the same medication from a tiny glass, drawing on a huge bottle. We all used the same glass. This procedure would be repeated for “maag” (stomach). Whatever your gut issues, you were given the same medicine as everyone in the queue. On one occasion, the notorious commanding officer of the prison, Major PA Kellerman, was present when the medication was being administered, and he instructed that all those in the “maag” queue be given castor oil – a kind of laxative. I don’t wish to tell you what the result of that was: and we had only two toilets.

We returned to the prison building in formations of four, and then had to undergo a strip search. We often waited in line completely naked for more than 20 minutes. Young and old, father and son, brother and uncle, all had to go through this violation of our dignity and, often, impairment of our health. We were exposed to unbearably freezing conditions. The warders seemed to enjoy this. One by one we had to go to a waiting warder and hand over our clothing one item at a time to be searched. We then had to open our mouths and show our backsides to prove that we were not hiding anything.

Years later, we acquired an abridged copy of the prison regulations, which clearly stated that if a prisoner was to be strip-searched, it had to be done privately: “A prisoner must not be asked to strip in the presence of another prisoner.” Once we knew that, we refused to be searched in that manner again. The warder had to see us each separately, in an office, a procedure which took up a lot of time. We would undress slowly and then take ample time while getting dressed again. The authorities soon tired of this and resorted to frisking us.

Our hearts would sink when the bell rang in the morning. Many of us would fear what the day might bring. We worried whether we would escape punishment. The arbitrary sanction of “drie maaltye” (three meals) was used extensively by the prison. A warder would take your prison card for no apparent reason and have you deprived of three meals over a weekend.

Your last meal would thus be served on a Saturday at about two, and then you would be locked up in a separate cell until Monday morning, when you would have breakfast and go to work in the quarry. If you escaped “drie maaltye” during the day, you considered yourself lucky. I starved over many, many weekends.

In any case the food given to us was always insufficient. This meant food smuggling was a constant problem on the island, often emanating from the store. Warders and common law prisoners would steal from our supplies as soon as these were delivered to the prison, leaving us with less than we should have had – and it was not much, or nourishing, to begin with. As prisoners we were perpetually hungry.

Cruelty towards us on the island was routine, and many prisoners fell desperately ill. When we first arrived on the island, there was no toilet paper and we had to tear off pieces of cement bags. These were lying around from the construction work. This added considerably to our discomfort, but after a year, the prison authorities realised that the paper from the cement bags was blocking the sewage pipes, and they finally decided to give us toilet paper.

The other thing we desperately needed was a handkerchief to blow our noses during the lengthy days at the quarry. Many prisoners had ongoing colds and flu. Every Sunday during inspection, we would demand handkerchiefs and, finally, much to our surprise, we were all issued with pieces of red cloth for this purpose. At weekends, we would wash the cloths in the bathroom basins and hang them out to dry by tying them to the cell window grilles.

One weekend, Captain Naudé saw the red handkerchiefs all tied up and started shouting and performing, claiming we were “flying the red flag”. He demanded that all the communist cloths be confiscated immediately. ML/DM

[hearken id=”daily-maverick/9468″]

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

Comments - Please login in order to comment.