PCC EXPERT SERIES — OUR NATURAL RESOURCES

How to help smallholder farmers fight climate change

Reducing injustices embedded in the food and farming system will require a just transition and a resilient path in the agriculture sector.

The latest climate science reaffirms that global catastrophic weather conditions in the past decade can be attributed to climate change. Climate change, in turn, presents sustained threats to global food and water security. Food production systems are threatened by extreme disturbances in weather patterns, manifesting as increased frequency of droughts and floods.

Climate resilience is critical to ensuring food security. In the context of weather and climate, resilience refers to the ability of a system, community or society to cope with and recover from the adverse effects of climate-related hazards and to adapt to long-term changes without undermining food security or wellbeing.

Smallholder farmers produce approximately a third of the world’s food and are therefore critically important to food security, yet they receive the least financial support from climate finance agencies. Africa is home to an estimated 33 million smallholder farms, contributing up to 70% of the continent’s food supply. Furthermore, women account for 60% of Africa’s food production and are often disproportionately affected by climate change.

The uMgungundlovu District Municipality (UMDM) in South Africa, located in the KwaZulu-Natal Midlands, comprises seven local municipalities and is home to many smallholder farmers. Climate hazards that affect local communities in uMgungundlovu District include severe storms, flash floods and droughts. The Standardised Precipitation Evapotranspiration Index, used by the South African Weather Service to measure precipitation, evapotranspiration and drought, including long-term rainfall observations, has predicted severe ecological impacts and a warmer future for the region.

The uMngeni Resilience Project (URP) in UMDM aims to increase climate resilience of smallholder farmers via three key interventions: early warning systems, climate-smart agriculture and climate-proof settlements. Research — including my PhD thesis for the University of KwaZulu-Natal entitled “Climate Adaptation Finance and Food Security in South Africa” — on effects of the URP has revealed that climate adaptation finance enables smallholder farmers to build resilience to climate change.

Aim and study context

The URP aims to reduce the vulnerability of farming communities and small-scale farmers in the UMDM to the effects of climate change. Best practice is to increase climate resilience and adaptive capacity by combining traditional and scientific knowledge in an integrated approach to adaptation.

In the UMDM, a set of complementary interventions were implemented to enhance resilience. These interventions focused on early-warning and ward-based disaster response systems, use of climate-resilient crops and climate-smart techniques in new and existing farming systems, disseminating knowledge about adaptation and implementing policy recommendations.

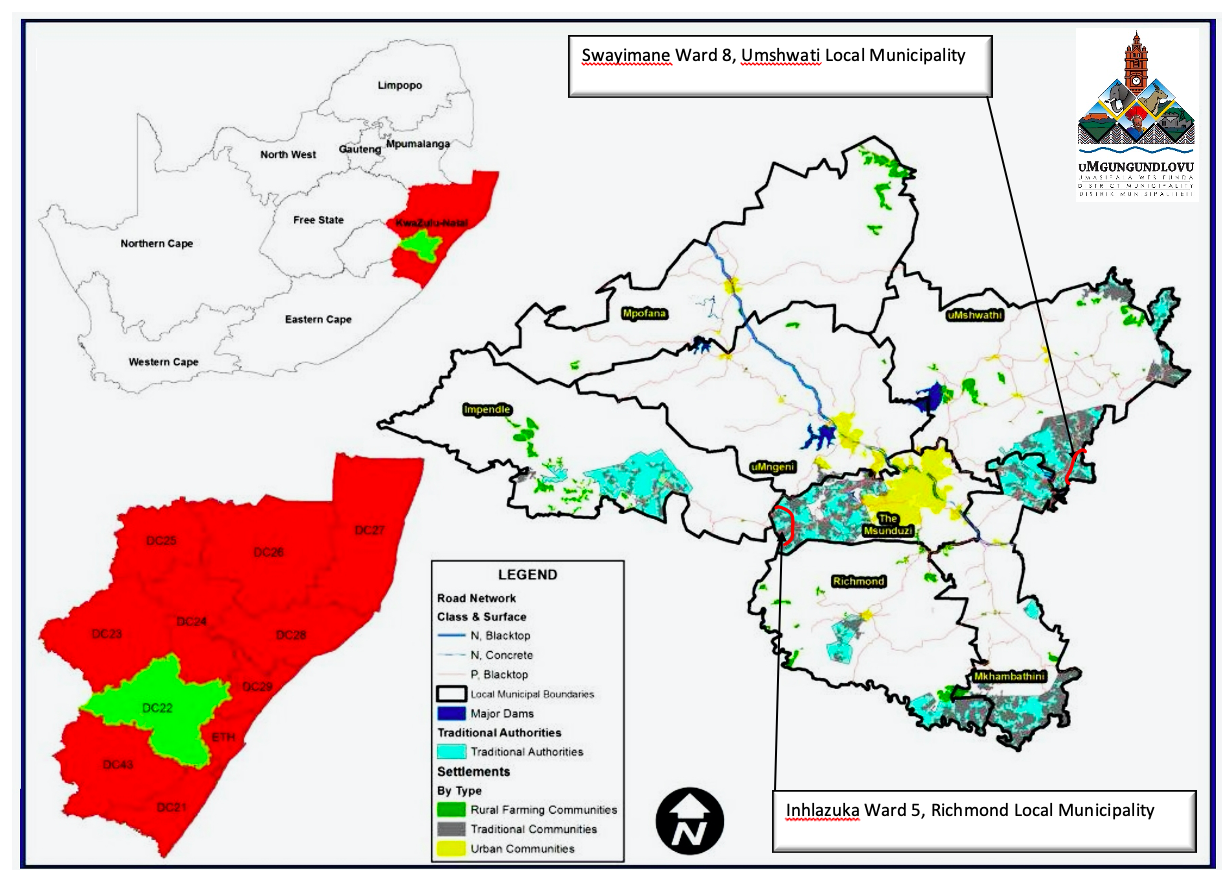

uMngeni Resilience Project Sites. (Sources: Sanbi [2014]; StatsSA [2011])

The first study site was Ward 8 of Swayimane under the uMshwathi Local Municipality (UMLM), which covers an area of 32.9km2, has an estimated population of 6,856 (53% women) and a density of 213 people per km2.

The second study site was Ward 5 of Inhlazuka, Richmond Local Municipality (RLM), which covers 103km2, has an 8,867 population (55% women) and density of 86 people per km2.

The rural sites were selected for their high level of poverty and associated vulnerability to predicted effects of climate variability and for the support of traditional authorities who embraced the URP. Income and livelihoods in both communities are largely derived from subsistence farming. Dominant farming systems include cropping and animal husbandry on gently sloping land. Farmers grow maize, beans, amadumbe (taro), sweet potato and sugarcane. The area is characterised by good rainfall (500 to 800 millimetres per year), predominant fog and deep soils.

The data collection process was guided by two frameworks: ‘vulnerability to resilience’ and ‘climate vulnerability and capacity analysis.’ These tools recognise individuals and communities as being vulnerable to climate change in several ways. The study adopted a mixed methods approach, with data collected using a questionnaire and focus group discussions. A total of 61 respondents (beneficiaries of the URP), composed of farmers from Swayimane (36) and Inhlazuka (25), were randomly selected and purposely selected, respectively.

Of the respondents, 48 (78.7%) were female; 44.3% were between 46 and 60 years old, and 37.7% were over 60. In addition, farmers took part in four focus group discussions (two in each research site) to explore other factors that help build resilience and to identify the benefits of climate finance.

Results[1]

The South African National Biodiversity Institute (Sanbi) and the UMDM obtained $7.5-million from the Adaptation Fund to implement four components of the URP.

For Component 1, $945,737 was allocated for early warning and response systems to improve preparedness and the adaptive capacity of local communities and small-scale farmers, while $3,197,307 was allocated for Component 2, climate-proof settlements.

The University of KwaZulu-Natal was awarded $2.11-million to implement the climate-smart agriculture (Component 3) and capacity-building (Component 4) interventions. The university identified smallholder farming groups and then financed adaptation interventions for them in the two settings: Swayimane and Inhlazuka.

The results indicated a considerable relationship between building resilience to climate change and access to adaptation finance. In both study sites, adaptation finance obtained from the URP supported the procurement of agricultural inputs, the establishment of climate field schools, the provision of low-cost adaptation technologies, and capacity building, including training on climate-smart agriculture. Farmers in Swayimane and Inhlazuka practised adaptation methods learned through the climate-smart agriculture training programme supported by the URP. Challenges that farmers mentioned included the shortage of water to irrigate their crops.

Water shortages are sometimes a real problem in this area of Inhlazuka; we sometimes use water from the stream to water our fields, but not everyone has access to a nearby stream, and those living further away from streams face major challenges from time to time. —MaZwide (Inhlazuka)

We uproot crops that are not drought-tolerant once we’ve seen that they are not doing well. —MaMngadi (Swayimane)

We dig trenches and furrows in our plots so that water is able to run off with minimal crops being washed away.—MaGogo (Swayimane)

In response to these and other challenges that farmers said they face, the University of KwaZulu-Natal designed a training programme on climate-smart agriculture. The first method that farmers learned and practised was the use of the A-frame to mark and plant, following horizontal or contour lines, and the digging of trenches to keep water underground and reduce run-off.

The intent of this method was to reduce soil erosion and conserve rainwater underground. This method was more favoured by farmers growing crops in sloped landscapes.

The second favoured method was the use of recycled grass cuttings and the minimal tilling method to conserve soil moisture. The third adaptation method encouraged the use of drought-resistant crop varieties to reduce vulnerability to climate change. Farmers with greater access to climate information and adaptation strategies through extension services were more likely to adapt to climate change.

Agricultural inputs included seedlings, such as bambara groundnut, cowpea, sorghum and millet. It will be crucial to develop seed production and storage systems for the identified crops, as well as soil preparation and cropping systems that are tolerant of climate risks. Other interventions included identifying water storage and irrigation systems, and providing equipment such as tractors, fencing tools and harvesting tools (hand hoes, garden forks, etc).

Adaptation funding

In Swayimane, Sanbi and the UMDM allocated adaptation funding in partnership with the University of KwaZulu-Natal to purchase and install an automatic weather station and an early warning lightning detection system to help the local community build resilience against climate hazards such as lightning. Seasonal harvesting influenced farmers’ decisions on food consumption and the marketing of agricultural produce.

Poor harvesting seasons influenced crop prices and the likelihood of selling produce at the market. Unfavourable climatic conditions such as drought threatened livestock and crop production, thus reducing smallholder farmers’ resilience to climate change.

Additional determining factors shown to help smallholder farmers better adapt included access to climate information, education (level of schooling and training received) and the application of climate-smart agriculture methods[2].

The education level of the household head, the farm size and the employment status of the household had no significant influence on adaptation to climate change. Focus groups revealed that education increased awareness of climate change, and regular access to weather information determined how smallholder farmers made informed farming decisions. Access to training enabled smallholder farmers to plant legumes for nitrogen fixation and soil rehabilitation. From the discussion, households with access to livestock appeared to have notably higher adaptive capacity.

Moreover, the URP described interesting lessons that contribute to policy planning and implementation. Women were more vulnerable to the effects of climate change due to their significant involvement in agricultural activities. Vulnerability in this context means exposure and susceptibility to the negative effects of climate change. Smallholder farmers played a limited role in how project funds were allocated and spent. There was no existential relationship between gender and awareness of climate change, suggesting that gender did not directly influence perceptions of climate change.

A just transition within the agriculture sector should be at the centre of climate policy in South Africa, with real inclusion of smallholder farmers and farming communities (See and Wilmsen 2020). A just transition in the agriculture sector should lead to the creation rather than the loss of jobs, and should reduce poverty and inequality. It should address women’s unequal position in society by increasing their access to land, education, finance, credit, food and health care, all of which build resilience. A just transition for adaptation is vital to ensuring the well-being of women amid resource scarcity and other stresses caused by climate change or by maladaptation, which can exacerbate conflict.

Injustices

Reducing the injustices embedded in the food and agriculture system will require a just transition and a resilient path in the agriculture sector. To build resilience to climate change, we must shift to more sustainable food systems that work for smallholder farmers, individuals and communities. The results of this study show that smallholder farmers in Swayimane and Inhlazuka can take action to strengthen their capacity to adapt to climate-related hazards and shocks. In addition, the results indicate a need to provide climate information through various extension services to increase climate resilience.

Farmers appreciated the adaptation methods they learned from the climate-smart agriculture training, which helped them better cope with climate shocks and stresses. These included adjusted planting dates to maximise crop yields, enhancing water- and soil-conservation methods, increasing crop diversification, increasing access to agricultural inputs (pesticides and fertilisers) and greater use of improved crop varieties.

In vulnerable rural communities within the UMDM, economic, sociological and technological interventions can make the management of drought and flash floods more effective. Moreover, women’s participation in project activities was factored into project indicators and targets to help them build resilience. Smallholder farmers played a limited role in the management of adaptation funds, particularly in terms of how funds were allocated and spent.

Hence, access to a comprehensive range of financial services remains a substantial challenge for smallholders. Institutional support mechanisms coupled with policy and technological interventions are needed to promote indigenous adaptation strategies that smallholder farmers and female-headed households can use to enhance their resilience. DM/OBP

Dr Sibusiso Nxumalo is a climate finance specialist adviser at the International Development Group.

Read Part One, Part Two, Part Three, Part Four, Part Five and Part Six.

This essay is part of a series that explores challenges and opportunities relating to a just transition in South Africa, with a specific focus on enhancing resilience in ways that improve lives and livelihoods. The series is being published in the lead-up to the Presidential Climate Commission’s multistakeholder just transition conference on 5 and 6 May. This essay series has been produced by the Presidential Climate Commission Secretariat and New Climate Economy, with support from the Danish Ministry of Foreign Affairs. The interpretations and findings set forth in the essays are the authors’ alone.

[1] For more detailed results see my PhD thesis “Climate Adaptation Finance and Food Security in South Africa,” soon to be made available online through the University of KwaZulu-Natal, Pietermaritzburg

[2] These methods included training in climate-smart agriculture (CSA) practices, demonstration of climate-smart options at the farm level and financial and other support available for supporting CSA implementation.

[hearken id=”daily-maverick/9419″]

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

Comments - Please login in order to comment.