STYLE

Men and jewellery: To bling or not to bling

Throughout the ages and in various cultures men have worn jewellery, both for ornamentation and as an external display of power and status, yet the more recent notions of masculinity have attempted present self-adornment as a gendered and strictly feminine affair. History suggests this is not the case, and it never was.

‘In a gentleman’s dress any attempt to be conspicuous is in excessively bad taste. If you are wealthy, let the luxury of your dress consist in the fine quality of each article, and in the spotless purity of gloves and linen, but never wear much jewelry or any article conspicuous on account of its money value. Simplicity should always preside over a gentleman’s wardrobe,” writes Victorian-era author Cecil B Hartley in the 1860 title, The Gentlemen’s Book of Etiquette and Manual of Politeness.

Over the following pages of this chapter of the book, simply titled Dress, Hartley offers advice on several elements of the gentleman’s dress code, the kind that certainly wouldn’t make sense in the current blinged-out hip-hop era. “All extravagance, all splendor, and all profusion must be avoided,” the author proclaims. Of colour, Hartley states unequivocally: “All bright colours should be avoided, such as red, yellow, sky-blue, and bright green.”

Gentlemen are also advised to shave, keep their hair short, take regular sponge baths, keep their nails clean and file them regularly into an oblong shape. However, “the length of the nail is an open question. Let it be often cut, but always long, in my opinion. Above all, let it be well cut, and never bitten… The man who upholds order is not conscientious if he cannot observe it in his nails.” As for “wigs and false hair”, Hartley “shall say nothing here except that they are a practical falsehood which may sometimes be necessary, but is rarely successful”.

But it is the disdain for bling that Hartley returns to later in the chapter, driving the point home for the would-be gentleman who might have failed to take the earlier admonishment to heart. This time, to truly shame those who might err on the side of ornamentation, Hartley plays on the sexist and racist fears that readers might harbour: “Jewels are an ornament to women, but a blemish to men. They bespeak either effeminacy or a love of display. The hand of a man is honored in working, for labor is his mission; and the hand that wears its riches on its fingers, has rarely worked honestly to win them. The best jewel a man can wear is his honor…

Recording artist Lil Pump attends the 2018 Billboard Music Awards at MGM Grand Garden Arena on May 20, 2018 in Las Vegas, Nevada. (Photo by Frazer Harrison/Getty Images)

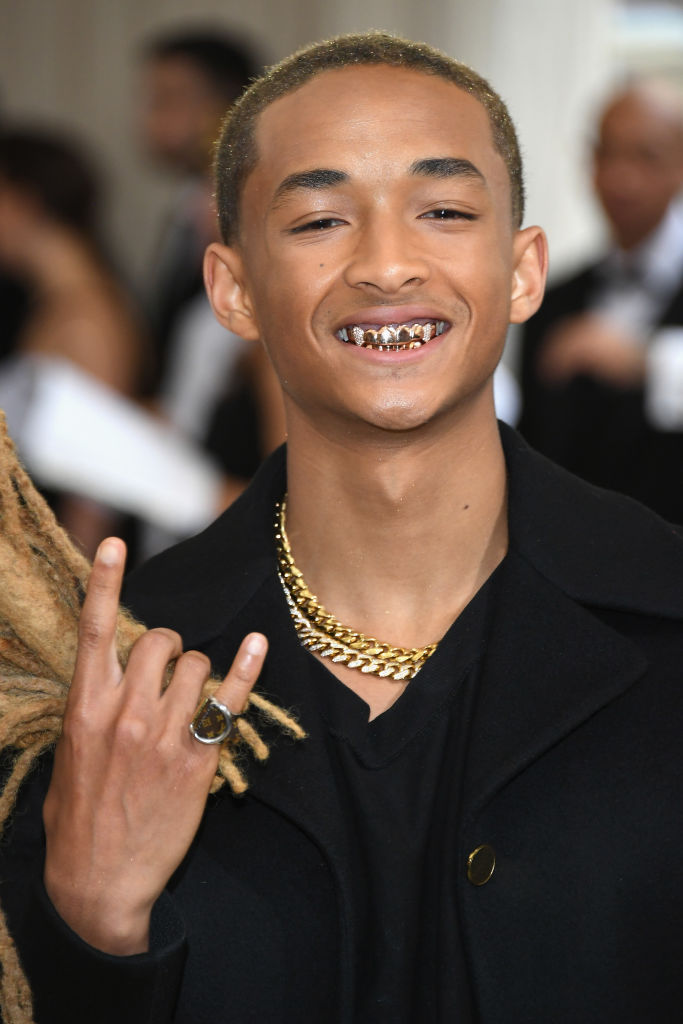

Jaden Smith attends the “Rei Kawakubo/Comme des Garcons: Art Of The In-Between” Costume Institute Gala at Metropolitan Museum of Art on May 1, 2017 in New York City. (Photo by Dia Dipasupil/Getty Images For Entertainment Weekly)

“I am quite serious when I disadvise you from the use of nose-rings, gold anklets, and hat-bands studded with jewels; for when I see an incredulous young man of the nineteenth century, dangling from his watch-chain a dozen silly ‘charms’ (often the only ones he possesses), which have no other use than to give a fair coquette a legitimate subject on which to approach to closer intimacy, and which are revived from the lowest superstitions of dark ages, and sometimes darker races, I am quite justified in believing that some South African chieftain, sufficiently rich to cut a dash, might introduce with success the most peculiar fashions of his own country.”

Musician Lenny Kravitz poses backstage a the 32nd International Emmy Awards ceremony at the New York Hilton Hotel November 22, 2004 in New York City. (Photo by Evan Agostini/Getty Images)

American pianist and singer Liberace, born Wladziu Valentino Liberace (1919 – 1987), showing off some of his jewellery upon his arrival in London, 28th November 1977. His rings are worth around £110,000. (Photo by David Ashdown/Keystone/Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

However, Hartley does make some concessions in recognition of the view that even gentlemen “are savages, and must have some silly trickery to hang about us…” Hence, if he must, a gentleman may wear “one handsome signet-ring on the little finger of the left hand, a scarfpin which is neither large, nor showy, nor too intricate in its design, and a light, rather thin watch-guard with a cross-bar”.

These days, it is largely accepted that Cecil B Hartley was not a gentleman at all, but rather the alter-ego of Florence Hartley, the very much female author of The Ladies’ Book of Etiquette and Manual of Politeness, and The Ladies’ Hand Book of Fancy and Ornamental Work.

While her books are arguably a reflection of the era in which they were published, they also belong to the “conduct book” genre, which started long before Hartley’s time, back in the Middle Ages.

In fact, the 19th century marked a decline in the popularity of the genre. Still, these books played a significant role in constructing and entrenching ideas of what was acceptable as masculine or feminine; ideas which were then spread around the globe as part of Britain’s centuries-long imperial exercise, and they still linger to this day, informing behaviour and dress around the world, including the kind of jewellery men feel comfortable wearing, with many strictly sticking to the watch and ring combo.

However, for centuries, before authors such as Hartley would put ink to paper and confidently proclaim that “jewels are an ornament to women, but a blemish to men”, men in cultures the world over have worn all kinds of jewellery, from the subtle to the ostentatious, be it for ornamentation, outward displays of power and wealth, or religious reasons.

Circa 1502, Montezuma II (1466 – 1520) the last Aztec Emperor who succeeded to the title in 1502, dressed in clothes inlaid with jewels. (Photo by Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

“Jewellery was man’s answer to the profound human need for self-adornment and, consequently, is one of the oldest forms of decorative art. For the past seven thousand years, its history – albeit interrupted and incomplete – can be traced from the centres of the earliest known civilisations in Mesopotamia (Iraq) and Egypt to its universality in modern times,” writes the late author and scholar Hugh Tait, in his introduction essay to the British Museum’s 1976 title, Jewellery Through 7000 Years.

In its 281 pages, the book is filled with images and descriptions of jewellery from various countries and cultures, all of which are part of the museum’s collection. It is worth mentioning that this being an edition of the book well over four decades old, the question of how these were acquired or who should be keeping them is, unsurprisingly, not broached, presumably partly because this was not a conversation as mainstream then as it is today.

However, paging through the book, seeing and reading about various pieces of jewellery, from Egyptian to West Asian through to West African, it is clear that rather than indicate gender, more often than not the wearing of jewellery denoted status, with precious metals often found in the tombs of kings and queens.

In fact, even in English history, one of the most famous royal portraits, that of 16th-century Henry VIII by Hans Holbein the younger, depicts a man wearing so much blinding bling he would surely be the envy of chart-topping rappers. There are precious jewels on the brim of his hat, on his sleeves, around his neck and all over his chest. And there are numerous other paintings, not necessarily of royalty, depicting men from the Renaissance period, completely “iced-out”, to borrow a hip-hop term.

A close-up of a portrait of Henry VIII by Hans Holbein the younger. Image: Art Gallery of South Australia (AGSA)

A portrait of Gustavus III of Sweden, painted in 1777. Photo: Alexander Roslin / Wikimedia Commons / Public Domain

Jacob the Jeweler, musician Pharrell Williams and Designer Nigo attend the store opening of “Nigo’s A Bathing Ape” January 11, 2005 in New York City. (Photo by Paul Hawthorne/Getty Images)

Pharrell Williams of N.E.R.D. poses for a photo during an in-store appearance at FYE March 23, 2004 in New York City. (Photo by Scott Gries/Getty Images)

Besides ostentatious jewellery in precious gems, and a bit closer to home in South Africa, it is also evident when looking at various forms of traditional cultural attire that jewellery in the form of glass beads often forms part of men’s or women’s attire in varying and sometimes similar amounts.

For many a South African couple, depending on their particular culture, a wedding is spread across two ceremonies – a day for the “white wedding” with the bride in her white dress and the groom in a suit, and another day for the traditional wedding, in traditional attire. Some, arguably more subtle versions of the latter often focus on fabrics with African-style pattern designs, while others, as often seen among Xhosa couples, might see the groom dressed in a version of umbhaco, the plain white wraparound skirt with lines of black piping stitched along the hem, and then for the groom’s upper body, several beaded necklaces layered across and around the chest, as well various beaded headbands.

Baby Cele during her traditional wedding on October 05, 2019 in Durban, South Africa. The event, which was held at Cele’s Umlazi home, was the renewal of vows for the couple. (Photo by Gallo Images/Daily Sun/Jabulani Langa)

Mandla Mandela (grandson of former SA president Nelson Mandela) and his French wife Anais Grimaud during their traditional wedding at the Mvezo royal palace in the Eastern Cape on Saturday, 20 March 2010. (Photo by Gallo Images/City Press/Khaya Ngwenya)

President Jacob Zuma married his fifth wife, Thobeka Madiba-Zuma on 4 January 2010 at his rural Nkandla homestead in Kwazulu-Natal. Pictured: Inkosi Mandela, grandson of former president Nelson Mandela. Feature text available. (Photo by Gallo Images/YOU/Tumelo Leburu)

Even with the policing of masculine aesthetic expression over the past two to three centuries, that “profound human need for self-adornment”, that Tait speaks of, remains; be it merely for ornamentation or, indeed, to say something about one’s place in the world.

From “Meet The Barkers” Travis Barker makes an appearance on MTV’s Total Request Live on April 6, 2005 in New York City. (Photo by Peter Kramer/Getty Images)

A festival-goer with facial piercings attends the 2014 Wacken Open Air heavy metal music festival on on August 1, 2014 in Wacken, Germany. Wacken is a village in northern Germany with a population of 1,800 that has hosted the annual four-day festival, which attracts 75,000 heavy metal fans from around the world, since 1990. (Photo by Sean Gallup/Getty Images)

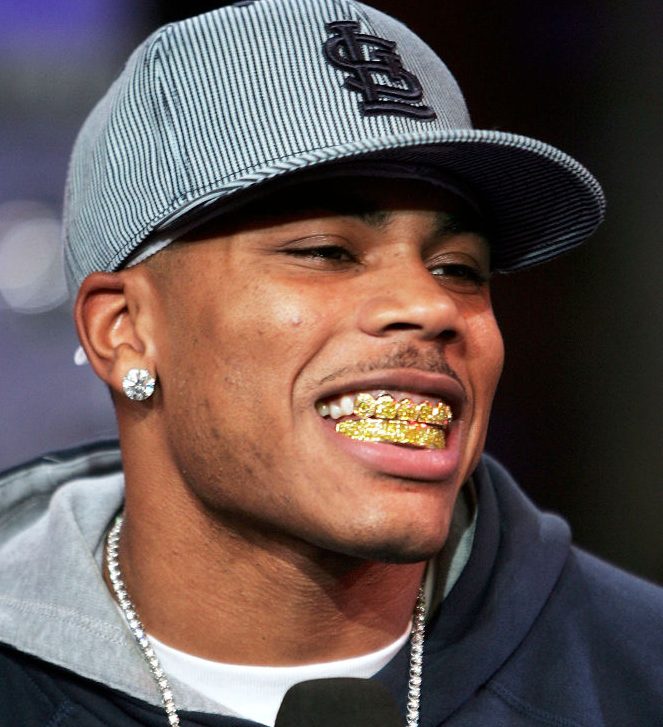

Rapper Nelly appears onstage during MTV’s Total Request Live at the MTV Times Square Studios on November 16, 2005 in New York City. (Photo by Scott Gries/Getty Images)

A full century after the publication of Hartley’s books, in the 1960s, the West saw men’s jewellery make a slow but steady return to the mainstream; from the hippies and their peace pendants, to the stylings of entertainers like Liberace, through to the chains and pendants hanging on many a hairy chest in the Seventies. And as hip-hop took over popular culture in the late Eighties and Nineties, a gold chain and an excessive amount of bling was once again not a matter of gender, but of status, aesthetic preference and, occasionally, rebellion.

Without a doubt, Hartley’s rules for gentlemen still exist, and many men are still wary of wearing conspicuous jewellery. Thankfully, in the age of bling and facial piercings, expression through self-adornment needn’t be limited by outdated notions of masculinity, unless one chooses such limitations. DM/ML

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

Comments - Please login in order to comment.