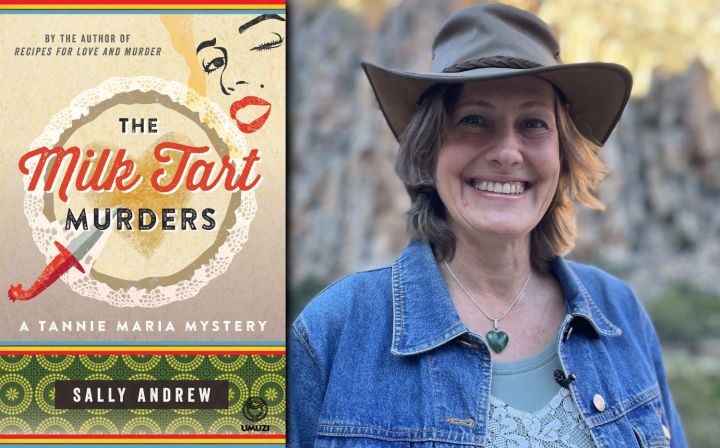

BOOK EXCERPT

Tannie Maria, the Klein Karoo crime-buster, is back in ‘The Milk Tart Murders’

South African author Sally Andrew’s new novel in the Tannie Maria Mystery series is out: Tannie Maria ditches her veldskoene for a day out at Oupa Frik’s vintage bioscope. Of course, things take a dark turn…

For those looking for a double dose of Tannie Maria, the TV adaptation of the series, “Recipes for Love and Murder”, is currently showing on M-Net. Here is an excerpt of Chapter 2 of The Milk Tart Murders.

***

Every Saturday at 3 p.m. Oupa Frik showed a vintage movie at his treasure and junk shop in Mountain Road, Ladismith: Oupa Frik’s Fantastiques. It’s not a long drive from my place into town and Henk and I arrived early in his Toyota bakkie. My bakkie was having a day of rest in my driveway.

We parked next to Frik’s low white wall. The small wooden gate was open and we wandered up the paving stones into the garden of his big Cape Dutch house. Though I’m not sure if ‘garden’ is the best word for it. There was a row of rose bushes along the wall, and some trees and spekbome, and green patches of vegetables, but most of the space was filled with sculptures and old-fashioned signs advertising products and movies from long ago. ‘Ouma Grietjie’s Soap’. Gentlemen Prefer Blondes.

At the far end of the garden was a pink Cadillac raised up on the rusted chassis of a tractor. ‘Oupa Frik’s Fantastiques’ was painted in black on the side of the Cadillac. In the middle of the garden was a circular washing line with a collection of enamel treasures hanging from it: pots and pans, a watering can, a red kettle …

We walked up the path, passing a green cast-iron bath with a metal sculpture of a cat and an owl sitting facing each other. The cat was holding a spade as if it was a paddle. There was a small sign stuck on a post in the ground that read ‘The Owl and the Pussycat’.

The elegant old house with its white gables did not match the crazy garden. But it somehow worked. Like a respectable ouma, watching her grandchildren playing wild games.

There were a few people in the garden. Jessie and her boyfriend, Reghardt, were sitting on a love seat made from tractor seats, their legs facing opposite directions. Around them was a frame of poles with pitchforks pointing inwards. It also had a sign on a little post: ‘Love Hurts’. Jess and Reghardt were nuzzling noses, and Elna le Grange was staring at them with wide eyes but trying not to. In some ways Ladismith is stuck in the old South Africa – many people are still shocked to see a white man with a coloured woman.

When Jessie spotted me, she jumped up, nearly poking her eye out with the prong of a pitchfork. She wore her usual black tank top and faded jeans. Her thick black hair was tied back in a ponytail. On her upper arms were her gecko tattoos, enjoying the spring sunshine.

I was wearing my cream dress with the blue flowers, and my blue shoes with low heels for my Saturday-afternoon date. I am happier in veldskoene, but sometimes my feet like to dress up too. I also carried my brown leather handbag; it has a long strap that hooks over my shoulder.

‘Tannie M,’ Jess said, giving me a big hug. ‘You look nice.’

Jessie Mostert is my friend and co-worker at the Klein Karoo Gazette – she’s our young investigative journalist. The girl with the gecko tattoo. Seeing Jess filled me with a warm feeling; she was as good as cake that way.

Reghardt joined us, and he and Henk nodded at each other. Warrant Officer Reghardt Snyman works with Detective Lieutenant Henk Kannemeyer at the Ladismith police station. He’s a tall, slim man with beautiful eyes – dark, with thick brows and long lashes.

We walked along the path together, passing a vegetable patch. A pair of mossies was studying the tomatoes to check if they were ripe.

There were two steps that led onto a veranda with low white walls and no roof. We were greeted by Helmina in a pretty pale- blue dress; Helmina was Oupa Frik’s personal helper and shop assistant. She had a round brown face and a smile like sunshine. Which helped, because these days Oupa Frik was mostly like thunder.

The old man sat on his stoep in a wooden chair, and scowled. Frik was in his nineties, long and thin. His face and hands were freckled the way people with English ancestors get when they meet our African sun. I’m lucky I have my mother’s skin instead of my father’s.

Oupa Frik wore a grey fedora with a yellow feather stuck in the hatband, and rested one hand on a silver walking stick. He changed the hat feather according to the day of the week. Saturday’s was a bokmakierie’s. I can’t remember them all, but I’ve seen him wearing the feathers of a red-winged starling and an owl.

‘Good afternoon, Oupa Frik,’ I said.

Frik raised his hat, showing me his bald head with those same freckles on it.

Henk stepped forwards to shake his hand, but Oupa Frik shook his walking stick at him instead. ‘You policemen are blooming useless,’ he said. Frik spoke in an old-fashioned English way.

‘Good afternoon, Oupa Frik,’ said Henk.

‘It’s Frederick, actually, though I suppose it’s too late to start insisting on that now. How many times have I called the police station this month?’

‘Five times, Oupa Fri— Oupa Frederick,’ said Reghardt. He turned to Henk, and explained, ‘Oupa Frik has reported things moved around in his house. Nothing stolen. He told us that, um, the Americans are after him. We found no evidence—’

‘And what, may I ask, have you done about it?’ asked Frik.

‘We have done our best, Oupa Frikerick,’ said Reghardt. ‘But—’

‘I don’t need to rest. I’m as fit as a bloody fiddle, aren’t I, Helmina?’

He stood up and sat down again to prove it. Helmina helped him on the way down, which was a bit wobbly.

‘Yes, you are, Oupa Frik,’ she said loudly. ‘Fit and strong.’ To Reghardt she said, ‘He’s a little deaf but he doesn’t like his hearing aid.’

Frik looked at Henk as if he was the one who’d spoken. ‘You should be ashamed of yourself,’ Frik said. ‘Show your elders some respect.’

‘I’m sorry, Oupa Frik,’ said Henk loudly. ‘We—’

‘Don’t you tell me not to worry. How would you feel if someone came into your house, started moving things around?’

‘I wouldn’t like that,’ said Henk.

‘It gives me the collywobbles. Just yesterday, someone moved a pile of my papers. Helmina swears it wasn’t her.’

He glared at Helmina. She shook her head.

‘I ask her to stay out of my study,’ said Frik, ‘but someone’s been in there, I tell you. I’d wallop the bugger if I caught him, but a man’s got to sleep … Hey, Captain Ben!’

We turned to see a barrel-shaped guy with a thick pirate’s beard. It was the man who ran the antique shop in South Street. Captain Ben’s Collectibles. He was new in town – he’d been in Ladismith for only five years.

‘You blistering barnacle!’ said Oupa Frik. ‘You owe me money.’

Henk stepped aside and Frik shook Ben’s hand and then hit him on the ankle with his stick. While Ben hopped on one leg, the policemen escaped.

The tall wooden front door was open and we went inside, into what may once have been a sitting room with cottage-pane windows. Now it was Oupa Frik’s shop. Some of the junk and treasures were neatly arranged in glass cases, but most were laid out on shelves and tables in what seemed like a random way. I always liked to buy a little something to help keep Oupa Frik going. I flipped through a pile of dusty cookery books and looked at some kitchen utensils. I tested an eggbeater and the handle came off. There were some colourful ceramics behind glass: a duck, a milkmaid and other stuff. But they were too expensive – around R4 000 – and not really my style.

Jessie was looking through old postcards and Reghardt was examining the knives. He pressed the blades against his thumb; none of them was very sharp. Henk picked up a handsaw. I found a kitchen timer in the shape of a green frog. Its buzz was tired, which made it sound like a croak. It would do the job but you would have to be in the same room when it went off.

We paid Helmina for our treasures and our movie tickets; she’d come inside and was standing at the till. My green frog cost R20 and the movie R30. I put the frog in my handbag.

‘Move along, you tardy blighters,’ Oupa Frik shouted, as he walked into the house. ‘Time and Hollywood wait for no man.’

Opposite Frik’s theatre was a closed door with a sign that read ‘Library. No Entry’. Beyond that were other rooms, but Oupa Frik wasn’t letting any of us wander off now; he herded us into the movie theatre with his walking stick.

The cinema had probably once been a dining room, but now it was full of red velvet seats that Frik had bought from an old bioscope in Cape Town. There were red curtains hooked up on either side of a big screen. Frik went into the little projector room on our left, which had long black curtains instead of a door.

Helmina followed him. ‘It’s not three o’clock yet,’ she said.

‘I don’t need a vet, for goodness sake,’ said Oupa Frik. He wiped his forehead with a handkerchief. ‘Just bring me a glass of water.’ He fiddled with the projector. ‘I don’t know what’s happened to my black-and-white reel. All I could find was this sepia one.’

Dr Haasbroek was just in front of us, walking past the projector room. ‘How are you, Oupa Frik?’ he said. ‘Did you make that appointment for your check-up?’

‘My health’s top of the pops,’ said Oupa Frik. ‘You tell him, Helmina, how I climbed that ladder. But my life’s getting strange. Things being moved around. People following me. Everything turning sepia.’

‘What do you mean?’ asked the doctor.

But Oupa Frik just closed his black curtains.

We headed to our seats. Reghardt, Jess, Henk and I sat in one row. Soon the little theatre was full. There were about forty of us. I waved to some of the people I knew. I recognised everyone, apart from one man and one woman. Helmina turned off the lights and the cartoon started: Popeye the Sailor Man.

Henk held my hand. The movie was Some Like It Hot. Black and white. With Marilyn Monroe and Jack Lemmon. It was funny and sweet, and sometimes scary, when people were killed. For a while it seemed like everything was going wrong and there was no hope for the lovers. But then, in the end, everything turned out all right. Movies should always be like that because real life often isn’t. We need to live in hope, or else why keep going? We want to believe pain and sorrow are things that will pass with the wind, and that love and happiness can belong to us. Like the earth beneath our feet.

When the film was over, we were all smiling. We waited for the reel to be turned off and the lights to be switched on. But that didn’t happen. The white screen just kept on flickering.

Someone called out, ‘Wake up, Oupa Frik. It’s finished and klaar.’

Helmina had been sitting in the audience, but now she got up and went to the projector room and pulled open the curtain. A beam of pale light flooded out.

She screamed.

Then she said, ‘Hy’s dood. Oupa Frik, he’s dead.’ DM/ ML

The Milk Tart Murders: A Tannie Maria Mystery by Sally Andrew is published by Penguin Random House SA (R290). Visit The Reading List for South African book news – including excerpts! – daily.

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

Comments - Please login in order to comment.