Unpunishable Crime

The artists, the forgers and the murky market of fake art in South Africa

After centuries of neglect by the global art establishment, African art is finally becoming big business. This creates the conditions for a perfect storm locally. While the demand for, and value of, African art is rapidly increasing, the South African art market is notoriously under-regulated and vulnerable to exploitation and the spread of fake art.

With additional research by Emma Dollery, Sarah Hoek, Emilie Gambade and Malibongwe Tyilo.

It started happening in 2019. Pippa Skotnes would be sitting at her computer and an email would arrive from someone asking her to verify whether an artwork seemingly produced by her late father, world-renowned artist Cecil Skotnes, was really his work.

This, in itself, wasn’t unusual. What was out of the ordinary was that the artworks in question were not ones that were recognisable to Pippa Skotnes — unquestionably the world expert on her father’s oeuvre, and herself an artist and curator of distinction.

“The first one was from a gallery in Franschhoek,” Pippa Skotnes said, speaking to Maverick Life through an online call in 2021.

The gallery had sent her a picture of a Skotnes piece that was totally unfamiliar to her. The attached information on the work’s provenance — its history of ownership — claimed that Cecil Skotnes had given it to a student he was mentoring. Pippa found it “extraordinary” that she would never have seen this work, but the account of the provenance seemed compelling. She speculated that perhaps her father had been giving someone a lesson, and the work was produced in the course of that. The seller — who was the alleged student in question — had signed a police affidavit guaranteeing the veracity of his story.

If the work was faked, whoever did it was taking an audacious chance. Pippa Skotnes, who together with her brother is the copyright-holder of her father’s work, is the last person you should expect to be able to fool.

“I have a very rich photographic record of his work, and I’m very familiar with his period,” she said.

“Cecil did not sell a lot of stuff from his studio, and did not swap a lot. And my mother kept absolutely impeccable records.”

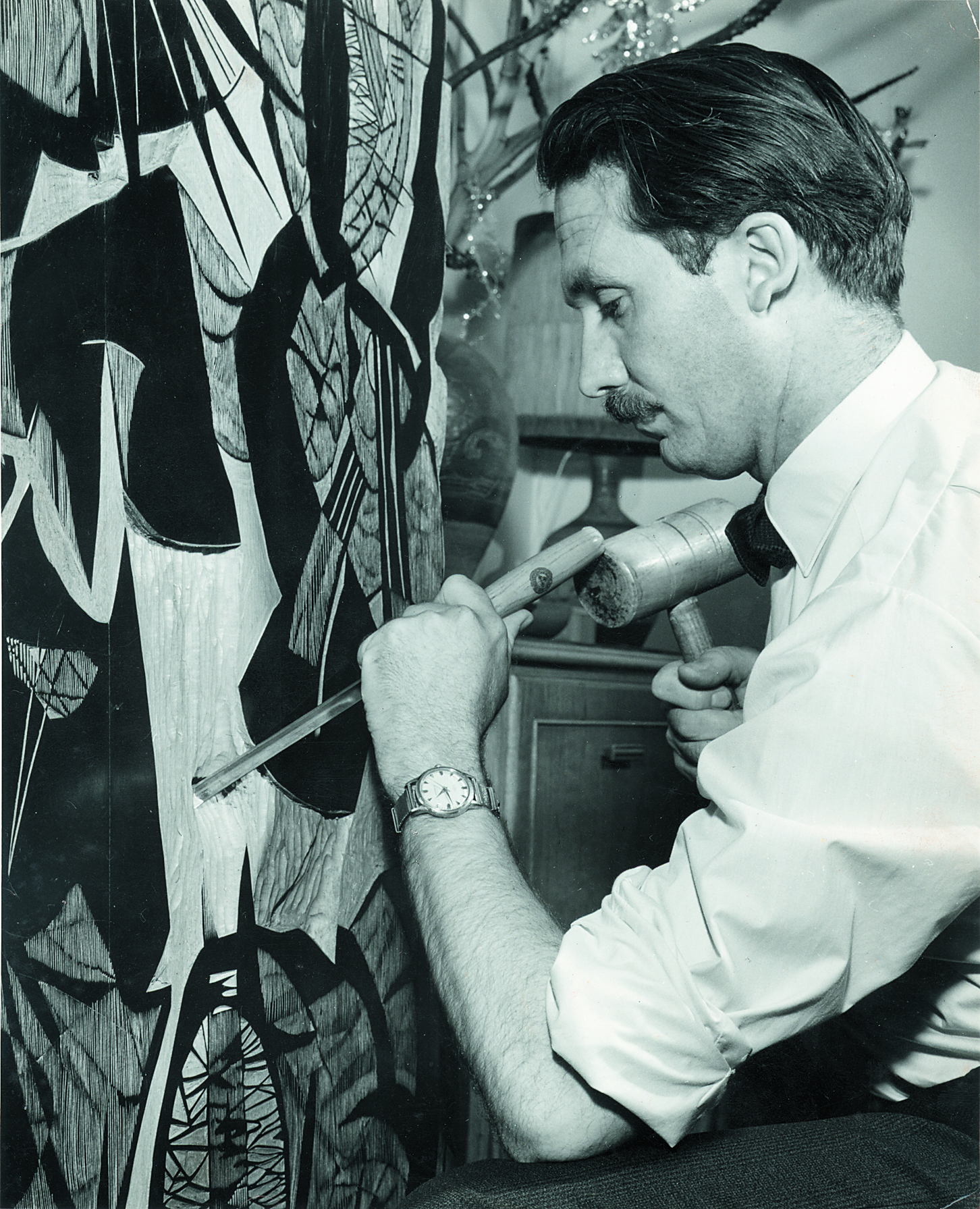

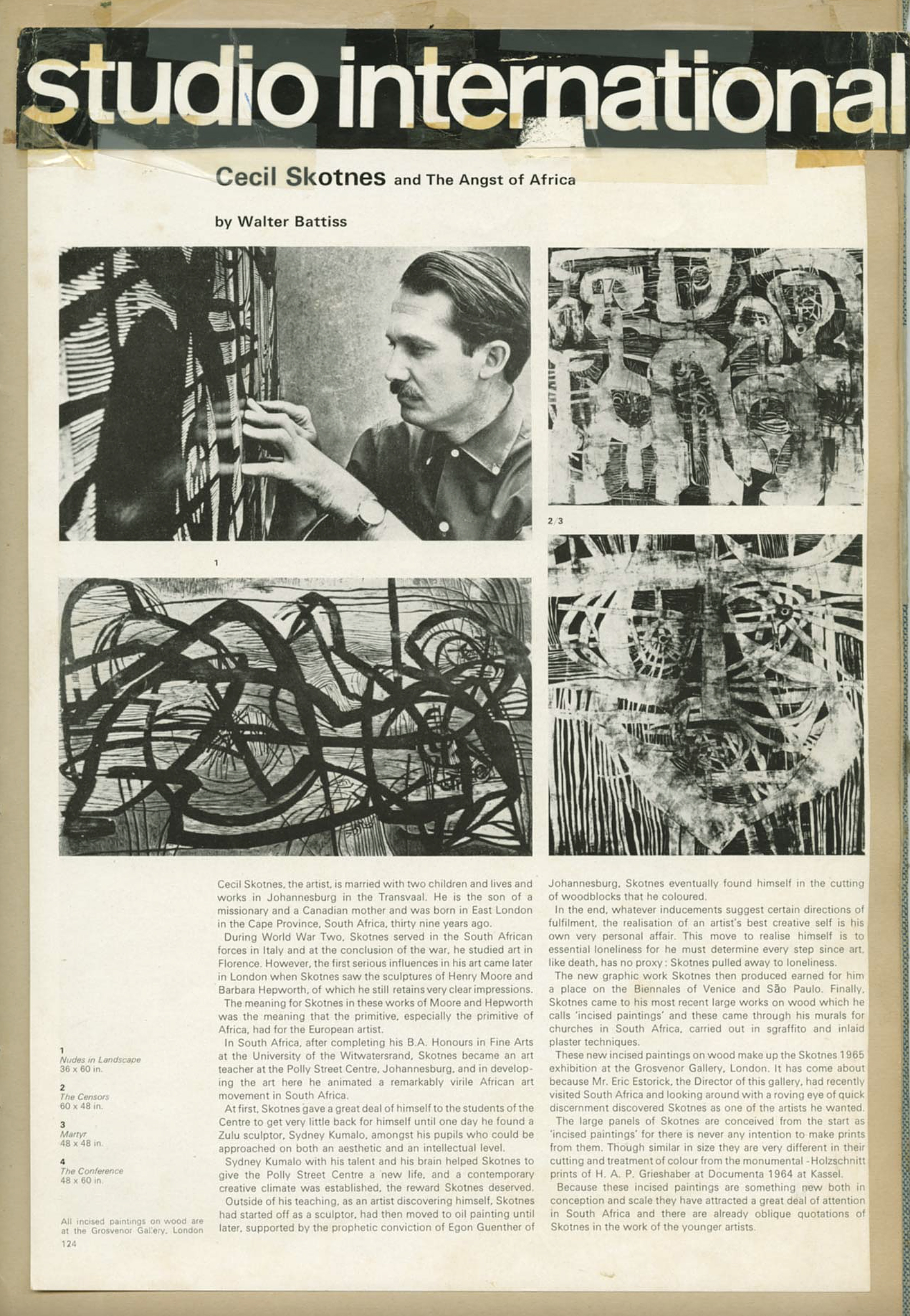

Cecil Skotnes at work. Image: Courtesy of Pippa Skotnes/ cecilskotnes.com

Archive. Image: Courtesy of Pippa Skotnes/ cecilskotnes.com

In addition, the artist had distinctive methods and tools of working.

“There are all sorts of tell-tale signs that you can point to: his use of colour, his use of shading, the confidence of his mark-making and cutting, the way he mixed paint and the direction of cutting.”

Pippa has kept her father’s paints and materials, too, which provide valuable additional clues. In short: if you’re going to fake a deceased artist’s work, Cecil Skotnes is a high-risk choice.

Panel (1960) by Cecil Skotnes. Image: Courtesy of Pippa Skotnes/ cecilskotnes.com

Portrait of a woman by Cecil Skotnes. Image: Courtesy of Pippa Skotnes/ cecilskotnes.com

Still Life by Cecil Skotnes. Image: Courtesy of Pippa Skotnes/ cecilskotnes.com

But in that first case, Pippa accepted that the work was probably indeed created by her father. In the months to come, however, similar mysterious works started arriving — over 20 of them to date, and some being sold by the world’s most respected art auction houses.

In short order, Pippa would come to a grim realisation: fakes of her father’s work were flooding the market, together with fakes of the work of his local peers.

“The whole school of artists of the same generation are being faked,” she concluded.

And even after she tried to raise the alarm, nobody really seemed to care.

***

After centuries of neglect by the global art establishment, African art is finally becoming big business. In April 2021, Sotheby’s bi-annual Modern & Contemporary African Art Auction netted $3.7-million in sales; more than R56-million at current exchange rates.

Individual pieces have also been reaching record prices. Nigerian artist Ben Enwonwu’s bronze Atlas sold at the Sotheby’s auction for $519,826 (over R7-million). In the same month last year, a Jacobus Hendrik Pierneef painting and an Anton van Wouw sculpture fetched R5.1-million each at a Strauss & Co auction in South Africa.

This creates the conditions for a perfect storm locally. While the demand for, and value of, African art is rapidly increasing, the South African art market is notoriously under-regulated and vulnerable to exploitation, as Diana Neille pointed out in a 2021 Maverick Life article.

“Very simply, there is an enormous number of fakes around,” is how Dr Alastair Meredith, a senior art specialist at Strauss & Co, put it to Maverick Life.

“We are seeing more fakes now than we ever have before. I’d like to think that we are more knowledgeable than we used to be. You know, I think maybe five or 10 years ago, people weren’t maybe as suspicious as they are now. But the reality is, we have for a long time realised that there are a number of artists who are faked extensively.”

Meredith’s candour on this point is not the norm. Over the course of a months-long investigation by Maverick Life, we repeatedly encountered expressions of disbelief, apparent lack of knowledge or lack of interest from individuals in South Africa’s art industry when questioned about the growing problem of fakes.

There are some very good incentives for industry figures to close ranks and deny that forgery is widespread within the South African art world. For galleries and auction houses to acknowledge that they may routinely be selling inauthentic work would endanger their reputations and their bottom lines — even though, as will be seen, there is abundant evidence that this is indeed the case. It would also require them to drastically tighten their scrutiny of works that come up for sale, which is a time-consuming and costly business.

Meredith also argues that part of the problem lies with a lack of appetite for the truth from some of the people you might think would be most invested in it — art owners.

“When a fake comes into our office to be valued, we will try our best to convince the owner that the work is indeed a fake. And then we would suggest that they maybe take it back to where they bought it from, or donate it to the University of Pretoria who is building an archive of fake artworks. But if they say ‘no, I’d rather keep it,’ there’s nothing we can do. And often they just take it home with them. And more often than not, they end up taking it to another auction house and manage to sell it.”

The problem may be particularly acute when it comes to the work of dead 20th century black South African artists. Their once under-appreciated work is finally receiving the attention it deserves — which also means that it is now also at the mercy of the fake art market.

Highlights from Sotheby’s auctions of Modern and Contemporary Middle Eastern and African Art at Sotheby’s, featuring The Visitor by South African artist Gerard Sekoto on March 20, 2020 in London, England. (Photo by John Phillips/Getty Images for Sotheby’s)

***

To understand why it can be so difficult to crack down on fake art, Maverick Life turned to two of South Africa’s only experts on this subject: Salome le Roux and Gerard de Kamper. Together, the two run a company called ART (Art, Research and Technical Analysis) Group, created specifically for the purpose of authenticating art, studying forgeries, and creating an archive of fake works.

For a long time, this type of expertise simply did not exist in South Africa, which is one of the reasons why forgery has flourished. De Kamper and another colleague, Isabelle McGinn, made national headlines in 2021 when they were able to prove that a Rembrandt painting owned by the University of Pretoria was a fake — in part because chemical analysis of the paint used showed major traces of barium sulphate, a substance which was only mined some 200 years after Rembrandt’s death.

The painting attributed to Rembrandt, was donated to the university in 1971. Image: Courtesy University of Pretoria Museums, CC BY-SA.

The experts believe that there are probably quite a few purported ‘Old Master’ paintings hanging in esteemed South African collections which are fake. Other than the lack of technical know-how to prove this, another reason why they have gone undetected to date is that it would have presented difficulties to have these paintings brought back to Europe in the early 20th century for expert analysis there.

Le Roux explained that they now investigate artworks according to a “three-legged stool”: provenance, connoisseurship, and technical analysis.

Says le Roux: “When those three legs work together, you can, not beyond all doubt, but fairly confidently assign an artwork to a specific artist. It builds a good foundation of proof for the authenticity of the artwork.”

The first leg of the stool, provenance, can be tested with reference to archival evidence of the work’s history. This could consist of old images of an artwork, or a description of the piece in a newspaper or catalogue, or a list of works in a collection. For most really famous Western artists, a catalogue raisonné will exist: a comprehensive listing of all the known works by an artist.

One of the reasons why 20th century South African artists are appetising to fake is because very few catalogue raisonnés are available, particularly of black artists’ work.

The technical analysis of artwork, Le Roux’s speciality, is the scientific analysis of a painting’s material make-up, to determine things like the age of the work, or the type of paint the artist used.

“We do x-ray fluorescence spectroscopy (XFR) and fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR). With those we can determine the pigments the artists use as well as the binding medium. In other words, was it an acrylic painting, was it an oil? What type of oil or acrylic was used?”

The final leg of the stool, connoisseurship, is perhaps the vaguest and least objective. Le Roux calls it a “learned science”, one in which an expert has seen so many works by a particular artist that they just have a sort of “gut feeling, that eye for when it is or isn’t”.

Connoisseurs become familiar, through extensive experience with the work, with things like the artist’s brushstroke, or the proportions that they will use: the kind of awareness that Pippa Skotnes brings to her father’s work.

If all three “legs” can be verified and match up, it is safe to assume the artwork is authentic. If an artwork is missing any of these elements, it makes it much harder. If one of the legs are clearly mismatching, then “we can rule it out as an original or authentic artwork”, says le Roux.

It’s evident that authenticating art is a complex process. But at the world’s top auction houses, which sell artworks for breathtaking amounts, one would assume this kind of due diligence would be routine.

***

In March 2021, an auction was held by the London-based firm Bonhams, which describes itself as “one of the world’s oldest and largest auctioneers of fine art and antiques”. Founded in 1793, Bonhams is — together with the likes of Sotheby’s and Christie’s — unquestionably one of the most elite and respected names in international art sales.

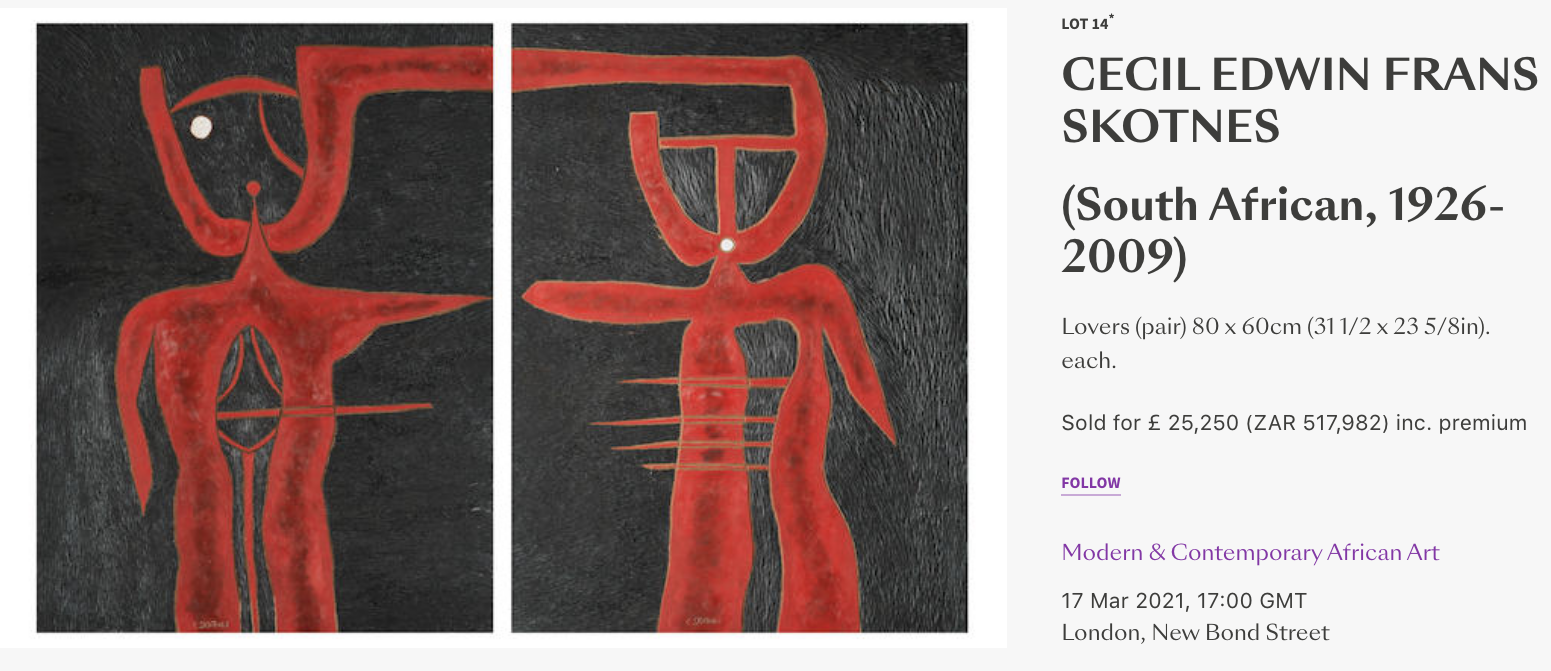

Lot 14 in this particular auction was a work that ended up selling for £25,250 (almost R517,000). It was titled “Lovers”, and advertised as being by the South African artist Cecil Edwin Frank Skotnes.

Lot 14, “Lovers”. Image: bonhams.com

Pippa Skotnes only learned of the sale once it had been completed, and she was immediately alarmed. She could tell that the work being passed off as her father’s was a fake — and, as she told Maverick Life, “not a very good one”.

Skotnes wrote to Bonhams at once to inform them that the work they had sold was a fake and to ask what they intended to do about it. She was politely brushed off.

Maverick Life had the same experience upon reaching out to Bonhams. We asked the auction house whether they had ever contacted Pippa Skotnes to confirm the authenticity of her father’s work, whether they would do so in future, and in general what steps they took to verify the provenance of the artwork.

The sole response Bonhams was willing to offer through a spokesperson, without elaboration: “Wherever possible, we check the provenance of works that we offer at auction.”

Roland Foord, a British solicitor who is one of the country’s foremost experts in litigation relating to art and “cultural property”, told Maverick Life that Bonhams’ response was essentially par for the course.

Even when it comes to elite auction houses selling expensive art, Foord said, the underlying principle of the transaction dates back to the ancient Latin warning of caveat emptor: buyer beware. In other words, there is an inbuilt risk that the buyer, rather than the auction house, takes on.

The person offering the work for sale through an auction house, Foord explained, “gives various warranties” to the auctioneers about the work. These would include the work’s provenance and the seller’s entitlement to sell it.

When it comes to the auction house’s scrutiny of the work, Foord said: “There is inevitably going to be a different level of diligence applied, depending on what the object is.”

If Bonhams is selling a Rembrandt which will go for millions of pounds, in other words, the auction house is much more likely to put in the hard work of authenticating it ahead of the sale. Though the Skotnes work may have sold for half a million rand, that is — in crude terms — peanuts compared to what other lots may raise.

“So how much diligence do you do on something that you know only has a market value of £25,000 when you’ve got a seller who is warranting to you that it’s their property that they’re entitled to sell, and how much expertise would you expect Bonhams to have in the work of Cecil Skotnes?” Foord asked.

Pippa Skotnes finds this reasoning outrageous.

“Bonhams, I feel very angry about,” she told Maverick Life.

“Maybe in pounds [the sale amount] is not a lot, but they should do their homework.”

***

If you are an art forger looking for an artist to fake, there are at least two good reasons why you might decide on someone like Cecil Skotnes.

The most compelling is the value of, and demand for, Skotnes’ work, examples of which routinely sell for hundreds of thousands of rand, and sometimes over a million.

The second is the fact that Skotnes’s neo-Primitivist style might seem easier to reproduce, particularly for someone with little formal art training, than an artist who works in a highly realist or representative style.

But forging a Skotnes, as mentioned earlier, also comes with a major potential challenge: the existence of a dedicated gatekeeper in the form of Pippa Skotnes, and the existence of relatively comprehensive record-keeping about his body of work.

This factor, in fact, makes Skotnes quite anomalous in the history of South African art, and particularly when compared with his black contemporaries. And that’s something that hasn’t been lost on forgers.

“The fake market has moved into black Modernist artwork,” says Gerard de Kamper, who arguably knows more about South Africa’s industry of fakes than anyone else, and tracks it more obsessively than anyone else.

De Kamper reels off a list of prominent black South African artists whose work is continuously forged: George Pemba, Lucky Sibiya, Gerard Sekoto, and many others.

“Currently I see new fakes every week. The moment an artist passes away, within a fortnight you see the first fake.”

Because of de Kamper’s niche expertise, he has become a go-to person for people worried about the authenticity of South African artworks. Although art fraud is sometimes portrayed as a type of crime eliciting little public sympathy — because the artists are dead and the buyers often very wealthy — de Kamper says this is far from justified.

“I just worked with a woman whose husband put all his retirement money in art. Of 42 artworks, only one turned out to be real. They lost over half a million rand.”

De Kamper says he has approached auction houses like Bonhams on a number of occasions to inform them they are advertising a fake work for sale. Sometimes, he says, “they will sell them without batting an eyelid, even if you write to them and say it’s fake”.

On occasion, he has had greater success. In June 2017, de Kamper saw that a small British auction house was selling a copy of a painting by South African artist Alexis Preller, which the firm was correctly not attempting to market as a Preller original: it bore the signature and date “GR 1977”, two years after Preller’s death.

“I joked, ‘One day we are going to see this with a Preller signature’,” de Kamper says.

“Less than a year later, lo and behold, there’s the same painting with a Preller signature. The original signature had been painted out.”

Bonhams put the painting up for auction in March 2018 as a Preller original, and de Kamper had spotted it by chance while sitting at the airport paging through an auction catalogue. Together with his students, he wrote a report on the painting and sent it to Bonhams.

“They withdrew it on the day of auction, but I could never get them to tell me what they did with it,” he says.

“About three months ago I saw a photograph of a collector with the same Preller fake. It’s in Johannesburg now.”

One of the elements that makes the behaviour of UK-based auction houses like Bonhams seem inexcusable is that, in the UK, there is a clear legislative framework around fake art and a dedicated police unit.

This is not the case in South Africa, where there have been very few — if any — successful prosecutions for art forgeries, much to the frustration of figures like de Kamper.

South African lawyers specialising in art are few and far between, but they do exist. One is Cape Town’s Toby Orford, who spoke to Maverick Life in 2021.

Orford reiterated the claim made by Strauss & Co’s Alastair Meredith: that often what prevents significant action being taken on art fraud is the owners of the art.

“Sometimes if they’ve bought a fake, they don’t want everybody else to know that,” Orford said.

“Very often they would like to keep it secret and just somehow or other find a way to release that work back into the art market.”

By doing so, Orford says, they become “part of the world of the art forger”, and the fake work continues to circulate as authentic.

Orford says that a person who buys a piece of art believing it is authentic and subsequently finds out it is fake does have a number of potential legal recourses, but they are generally only used by the “very determined and very rich”.

One would be to sue the seller for breach of contract. Parts of the Consumer Protection Act may apply to the buying and selling of art, depending on the parties involved and the transaction – but Orford cautions that “We’re not quite sure yet how effectively the consumer protection system would work out in practice in art world disputes”.

Part of the problem is that any such legal challenge requires establishing that a fake work is a fake and pinning legal liability on the seller – which, as previously noted, is an expensive and difficult process. Orford says one has to bear in mind the claimant’s burden of proof in a civil court of law, and the usual absence of a clear and undisputed “consensus of expertise”.

Another major issue is the much wider problem of the capacity of South African law enforcement.

Orford puts it bluntly: “We don’t have effective law enforcement agencies in our criminal justice system. So generally speaking, art crimes are not properly investigated or prosecuted in a civil and criminal law vacuum, and unscrupulous persons in the South African art market not surprisingly take full advantage of this situation.”

***

There’s one obvious, multi-million-rand question hanging over all of this: Who is forging the work of South African artists?

Gerard de Kamper may not know all their names — though he has some pretty good ideas — but he says one of the dark ironies of the situation is that some of the forgers appear to have a fair amount of talent themselves.

“The guy faking Lucky Sibiya — if he went out on his own, he might actually get somewhere as an artist,” de Kamper says.

Other suspected forgers do produce their own artistic work. De Kamper says that when it comes to some of the fake Skotnes works, “there is work you can connect it to on a stylistic level”. In other words, these suspected forgers’ own work bears some of the same artistic features an expert would notice in the fake Skotnesses.

There is one distinctly complicating element of the local art forgeries. Maverick Life was told by numerous sources over the course of our investigation that it is virtually an open secret in the South African art scene that some of those who are involved in the production and selling of fake work — particularly of the black Modernists — are the artists’ own family members.

Toby Orford sees it as part of a wider and very bleak tale of South African art history.

“[During apartheid the black modernists] were producing quite advanced works, but a typical art gallery in a big city in South Africa just wasn’t promoting them. They were being ignored,” Orford said.

“Artists bear the burden of understanding and managing their own copyright, and in the post-apartheid era many older artists are vulnerable because they didn’t sell or become household names in their lifetimes. When they die, their copyright is transferred to their heirs who pick up bits and pieces but don’t fully understand the complex copyright ownership system.”

Orford says that in the absence of people helping artists and their heirs to legitimately generate financial benefits from the artwork, those who have tended to become involved “are more often than not commercially self-serving and exploitative”.

Enter a number of unscrupulous individuals – including white art dealers – who promised family members that there was money to be made.

One of the ways of doing this was persuading the family to sign off on dubious provenance accounts of certain artworks, in exchange for percentages of the sale.

During our investigation, multiple sources advised Maverick Life to look into the practice of Martin Britz, an art dealer who runs an online shop called the Soweto Fine Art Gallery. In 2021, Britz’s website advertised as sold an artwork by Cecil Skotnes titled ukumemeza, which Maverick Life drew to the attention of Pippa Skotnes. She confirmed that the work was fake, explaining:

“There is no record of this as having been exhibited or commissioned, nor any photograph of it. Engraved details are uncharacteristic. Cutting and use of engraving as surface decoration is uncharacteristic. Some of the shapes are implausibly clumsy and tonal gradations and use of line are all uncharacteristic. While there are similarities in palette, the gradations of colour and surface texture is uncharacteristic. The style of the work is very similar to another identified as fake for other reasons.”

When Maverick Life contacted Britz to ask him about this and other matters, sending him a list of questions, he responded by accusing us of “unethical and unconstitutional conduct”, and threatening legal action.

Britz accused us of acting in collusion with an unnamed “third party” whom he alleged was on a mission to “collect evidence against me, my company and my associates with the intention to launch a malicious media smear campaign against me, threatening that this would destroy the good name and reputation of me, my company and my associates in the industry…I have reserved my rights in this matter to proceed civilly as well as criminally against said third party, and or any other party/parties involved and enabling these actions”.

But just when it seemed that those responsible for South African art fraud might happily continue their crime without consequences forever, a virtually unprecedented press release was sent out on 3 December 2021 by South African specialised crime unit the Hawks.

“The Randburg Magistrates’ Court remanded two male accused in custody today charged with fraud involving a fraudulent exclusive Limpopo artwork,” it read, in the slightly odd phrasing of law enforcement.

“It is alleged that on Monday 29 November, the pair approached a Bryanston auctioneer selling a fake painting for approximately R600,000.”

The statement recorded that after a “sting operation”, 33-year old Brighton Ndlovu and 32-year old Mphilo Shongwe were arrested in possession of the painting.

Possibly nobody in South Africa was more excited about this news than Gerard de Kamper, who was quick to fill in the details for Maverick Life. The painting in question appears to have been a fake Pierneef, and the men selling it allegedly produced a pair of fake IDs and a false affidavit of ownership.

To de Kamper, the arrest suggests that a change in leadership in the Hawks unit responsible for heritage crime may be resulting in police finally taking the problem of art forgery seriously. To Pippa Skotnes, too, the development suggests tangible progress at last.

When Skotnes had first spoken to Maverick Life, months earlier, she had taken pains to explain why the forgery of her father’s work caused her so much distress. It wasn’t about the money, she said, or even necessarily about the legacy of Cecil Skotnes himself. It was about the fact that artists grapple with the truthful expression of the context of their time.

“We depend on the authenticity of items of heritage – including archaeological discoveries, rock paintings, physical traces of past lives – for they represent aspects of our past and expressions of truth that help us navigate the present,” Skotnes said.

“If heritage is forged or deliberately invented in order to deceive, then our understanding of the past and its effect on us in both the present and the future is at stake.” DM/ ML

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

People buy art for one of two reasons. Either because they appreciate the work and get pleasure from looking at in and are prepared to pay the cost of that pleasure, in which case why does it matter whether it is a fake or not. Or because like Bitcoin it will be easy money and will appreciate in value because of the greater fool theory, in which case they risk there being no value in the so called asset, it is stolen or the market crashes ( again like Bitcoin).

Thank you for a great and informative article.

The reaction of the auction house leaves a bitter taste.

Such a thoroughly well researched and constructed read. It would be ironic if our concern for artistic authenticity finally lifts the lid on SA’s raging appetite for rampant fraud amongst the elite and politically connected. Can you hear Cele saying: leave no painting unturned!? Not.

Does Rebecca Davis ever sleep? Given the quantity of her output, and the detailed research that must go into almost of it, I seriously doubt that she is getting a full night. Maybe she has an AI text generator . . . but no, no computer could imitate her quirky individual voice. Respect.

I see there are a few Skotnes’s on Auction this afternoon at Strauss & Co. in Cape Town (on line Auction from 2pm)

I wonder if Pippa has viewed those? Be interesting to get her view.