SPONSORED CONTENT

A Different Take on Stagflation Prognoses as an Outcome of the Ukraine War

Over the last few weeks, the Western world has been left reeling in shock at Putin's brutal attempt to turn a crumbling petro-economy into a new Russian empire, prompting various doomsday scenarios for a world still reeling from the Covid-19 pandemic.

As Russia wages war on its nearest neighbour, surging energy and raw materials prices have driven inflation to their highest levels in decades globally, and the spectre of stagflation looms. However, we don’t buy into the doom and gloom prognoses that tend to emerge during times of grave uncertainty and panic. While we do believe prices may not have peaked yet globally, we still expect inflation to eventually recede later this year – taking stagflation off the table.

At Prescient, we cautiously monitor economic themes, inflation dynamics, labour market trends, and market behaviour based on our deep and point-in-time analysis of big data sets. These always direct us to what we believe are scientifically correct conclusions based on the available evidence.

The war is devastating and looks set to worsen in the coming days and weeks. But the possible outcomes are clear cut and not likely to be too far away. Option one is a costly and ultimately unsustainable Russian occupation of Ukraine, while option two is a crumbling Russian attack as Ukraine keeps up the fight. Either way, the war will eventually de-escalate, even if the current circumstances point in a very different direction.

So what is the likely impact on global inflation, and why do we acknowledge inflation is here but view it as likely to be a temporary phenomenon? To answer this question, we must look at both sides of the Atlantic.

In the US, we’re looking at an almost energy-independent economy. While the oil-price surge has undoubtedly had a once off-impact on US inflation, it is going to be rather short lived. Our take has long been that the Federal Reserve still sees the current inflationary pressures as short-term in nature. Besides the spike in energy prices, we expect supply chain bottlenecks and other once-off effects to wane slowly. We see this thesis as strongly supported by long-term, forward-looking, market-related inflation metrics, like break-even inflation or inflation swaps, which are both only reacting sluggishly. There is a risk to our view, and we don’t want to sound complacent. But market pricing paints a very different story to the more catchy headlines we’re reading in the news.

The Fed is considering rate hikes for reasons that are not associated with the current oil price shock. The Federal Reserve Open Market Committee is convinced that a stronger global economy and tighter labour markets are key enablers for the US economy, allowing it to stomach higher interest rates. It is anticipated that the initiation of a mild hiking cycle will, in fact, foster financial stability. So should we then be worried about a labour market-inflected inflation push? The answer again is no, in our view. While we see higher wage growth due to higher labour demand, the link between consumer price inflation and wage growth is currently weak – at best. This is explained by the fact that it has been an era of significant productivity gains, especially in the US. Significant productivity improvements allow wages to rise while keeping inflation in check.

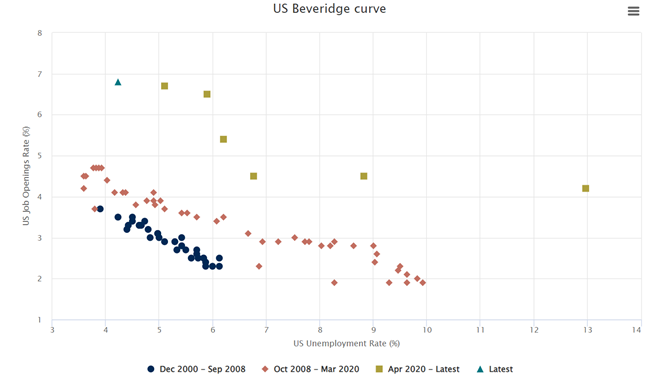

We plot the Beveridge curve in the chart below, which shows the relationship between the unemployment rate and job openings. The job openings rate is expected to affect the unemployment rate negatively. For example, as the economy expands, the unemployment rate generally falls, reflecting a decreased pool of excess workers.

Simultaneously, the job openings rate is expected to increase as businesses seek workers to fill new and existing jobs. Changes in the business cycle generate movement along the curve. At the same time, re-allocation of labour and capital between sectors, or a mismatch between an economy’s pool of available skills and the skills required to fill positions, moves the curve further away from the origin. We contend that the post-COVID US economy placed a high premium on productivity and roles that add to productivity. This has meant there’s been a culling of the labour force (particularly of older workers less able to assimilate new techno-centric skill sets), which, in turn, has contributed to lower labour participation rates but a more productive active labour force.

Source: Bloomberg as at end February 2022

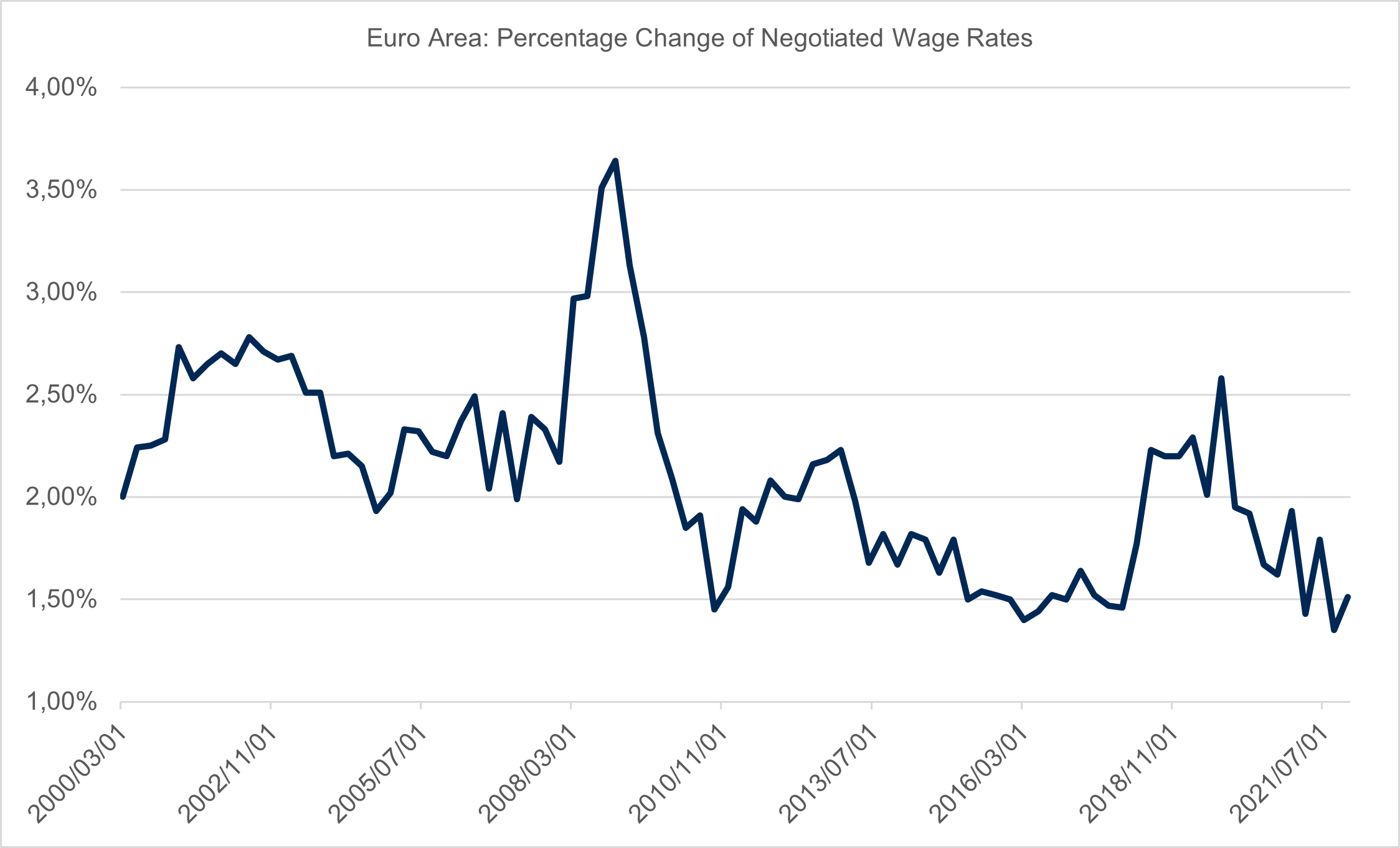

After looking into the US, let’s turn our attention to the other side of the Atlantic. In Europe, the war and the firm Western reaction is a massive external shock, leading to a primarily energy-driven once-off spike in import costs. Eurozone inflation looks set to surge to above 7% soon. These are numbers we cannot take lightly. However, at Prescient, we focus on cutting through the short-term noise and concentrate on the bigger picture, namely that inflation will almost certainly recede significantly again in Europe once the dust settles. Unlike the US, the Eurozone does not exhibit any home-grown inflationary dynamic. The chart below shows the year-on-year change in negotiated wages in Europe.

Source: Bloomberg as at end December 2021

Other than the impact on inflation, we also want to look into the growth perspectives for the developed world – for a time of heightened uncertainty and severe damage to business and consumer confidence. In the US and Europe, we can establish that the inflation shock to real disposable incomes affects many households, but at a time when they are sitting on substantial excess savings that they built up during the pandemic. Also, employment has risen to new records or looks set to do so shortly, on both sides of the Atlantic. By and large, household finances are – on average – in unusually good shape.

Even after paying much more for energy and food, many households still have greater spending power than usual. The same holds for most companies. And it’s important to highlight that in the developed and emerging world, our economies still have a lot of runway to recover from the global pandemic.

Once the initial shock has run its course, these fundamentals will likely reassert themselves. And it’s not just the economic fundamentals; it’s also the fact that these fundamentals still prevail in an environment that is benefiting from prevailing easy financial conditions. In our view, a longer-term stagflationary environment in the developed world is doubtful.

Markets will eventually start to price for this eventuality. Asset class returns are driven by more than just economics. At Prescient, we rely on a set of factors, including valuation metrics and a close assessment of financial conditions but also careful and point-in-time gauges of investor and market sentiment. Once again, it will be our point-in-time, data-driven approach that we will rely on to identify and process information in the timeliest fashion. We believe our approach gives us an information advantage, always ensuring that we adapt quickly and position ourselves well for any future challenges.

At Prescient, we are data-based and evidence-driven. We always follow processes informed by our investment themes and strictly make decisions with the support of statistically verifiable facts. But as human beings, we are also optimists. In geopolitical terms, our take is that the people of Ukraine’s courageous fight for freedom and the encouragingly united and robust response of the free world sends a strong signal to the rest of the world that Russia’s brutal and inhumane actions – and any other like these – will not be tolerated. DM/BM

Author: Bastian Teichgreeber – Chief Investment Officer, Prescient Investment Management

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

Comments - Please login in order to comment.