CABO DELGADO OP-ED

Investigation into arms flows to al-Shabaab insurgents points to Mozambican military

Since conflict broke out in Cabo Delgado in 2017, the weaponry used by the insurgents in northern Mozambique has become more sophisticated. Yet the source of these weapons has not been definitively determined.

Since the insurgent group known as al-Shabaab first began staging violent attacks in Cabo Delgado in northern Mozambique in October 2017, they have become a far more sophisticated and effective fighting force.

Early attacks in 2017 were carried out using a combination of machetes (widely available for agricultural use in the region) and locally available firearms. The first images of the insurgents shared on social media platforms reflect this, with AK-47s depicted alongside more rudimentary weapons.

Over the past four years, al-Shabaab (which is not connected to the Somalia-based group of the same name) has advanced both in its choice of weaponry and in its strategy.

They were able to withstand the response from Mozambican forces and two private military companies – the Russian paramilitary Wagner Group and the Dyck Advisory Group (DAG) – which were contracted to suppress the insurgency in the region in 2019 and 2020.

Al-Shabaab was able to capture and maintain control over large swathes of territory in Cabo Delgado, including holding the port town of Mocímboa da Praia for a year. The group also launched a successful attack on the town of Palma, a site of major developments in oil and gas exploitation in Cabo Delgado.

Since July 2021, intervention by Rwandan forces and SADC coalition forces has helped Mozambican forces to recapture some of this territory. Yet the conflict continues, and has resurged in parts of Cabo Delgado and spread into other provinces. Al-Shabaab has also re-established its connection with the Islamic State, as evident from Islamic State propaganda surrounding recent attacks.

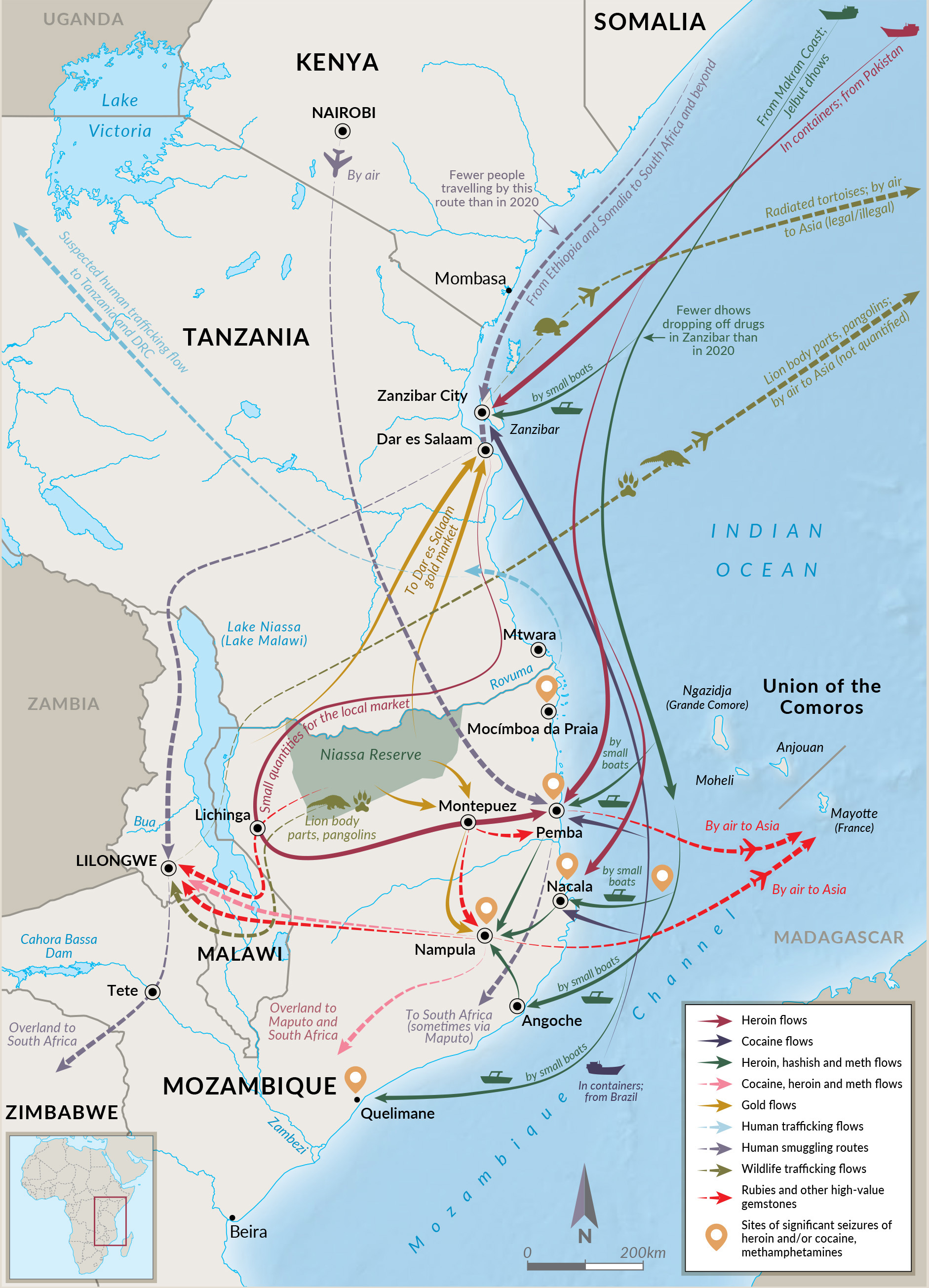

Several analysts have argued that al-Shabaab has also sourced weapons from outside Mozambique, arguing that this is how the group has become better equipped over time. Some have speculated that regional criminal networks have made use of northern Mozambique’s historical smuggling routes (transporting commodities such as drugs, illicitly procured gems and timber) to traffic weapons to al-Shabaab.

Recent Global Initiative Against Transnational Organized Crime (GI-TOC) analysis of the Cabo Delgado situation (which draws on research our team has been conducting in the region since 2018) has investigated this possibility and considered several other potential routes of arms flows.

Pre-existing sources of small arms in northern Mozambique

In the early days of the conflict, insurgents may have tapped into pre-existing sources and illicit flows of weapons in the region. In the lead-up to the insurgency in late 2017, AK-47s were available in northern Mozambique from several sources.

First, older weapons from Mozambique’s civil war (1976-1992) remained in areas where they had not been surrendered during the demobilisation process, particularly in locations sympathetic to the main opposition party Renamo (the Mozambican National Resistance Movement) or more generally in areas that were antipathetic to the governing party Frelimo (Liberation Front of Mozambique).

Second, AK-47s were smuggled into northern Mozambique from the Great Lakes region – in particular, Burundi and the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) – to supply a demand among ivory poachers operating in the Niassa Reserve and the Quirimbas National Park during the peak years of Mozambique’s elephant poaching crisis. However, as elephant poaching rates have been declining in northern Mozambique since 2018, this is no longer an active source of demand. Yet these weapons may have served al-Shabaab in the early days of its formation, particularly given reports of al-Shabaab recruitment among certain groups in the Niassa Reserve.

Finally, weapons from government sources have also regularly found their way into criminal hands, both for elephant poaching and for use by bandits. Banditry was already endemic in northern Mozambique long before the insurgency began, and illicit weapons still circulate for bandit use.

The earliest known photo of al-Shabaab insurgents, Mocímboa da Praia, October 2017. (Photo: Eric Morier-Genoud via Twitter)

Weapons sourced from Mozambican military

GI-TOC research in late 2021 concluded that the bulk of the insurgents’ weaponry comes directly from Mozambican military sources, and includes weapons captured from security force camps, border posts and police armouries in towns and villages overrun by the insurgents and abandoned by Mozambican security forces in retreat. This aligns with a detailed report from extremism analyst Calibre Obscura, published as our fieldwork concluded, which assessed the origin of al-Shabaab’s weapons using social media posts.

Images of weaponry shared either by the insurgents themselves or by coalition forces who have captured weapons from the insurgents are testament to this.

For example, footage shared by insurgents from the attack on Mocímboa da Praia in March 2020 shows a cache of weapons seized from an armoury in the town. This attack was a significant turning point in the scale of the conflict, not only because Mocímboa da Praia is a major town, but also because it provided the insurgents with access to further weapons in addition to looted cash. Similar footage and images shared on social media platforms also show types of weapons consistent with those used by Mozambican forces.

In September 2021, reports emerged that al-Shabaab had used an improvised explosive device (IED), created using a landmine, to target SADC forces. The landmine may have been looted from the armoury at the Namoto border post armoury in 2020, where some old landmines and mortar rounds had apparently remained. There have also been reports of test explosions taking place at insurgent field bases.

Sources connected to al-Shabaab report that some soldiers in the Mozambican armed forces (Forças Armadas de Defesa de Moçambique, FADM) had sold weapons to the insurgent group – particularly in 2018 and 2019, before it had become a major threat.

Interviewees described how al-Shabaab would stage an ambush, causing the military detachment to flee and leave their equipment behind, and making the loss of weapons, vehicles and other equipment appear accidental. A few of the insurgents (including senior al-Shabaab leader Ibn Omar) had reportedly served in the Mozambican military under the conscription system, and used former military contacts to arrange weapons transfers in exchange for payment.

Some sources allege that groups of soldiers formed by demobilised government forces or deserters had been paid to train al-Shabaab members in the early days of the insurgency when they were not yet considered a major threat. There are also reports of military supplies intended for military outposts being redirected to the insurgents in exchange for money.

Illicit flows through northern Mozambique. (Source: GI-TOC fieldwork in the region in November 2021)

Potential international arms flows

While the bulk of weapons used by al-Shabaab clearly come from Mozambican sources, there have been persistent reports about weapons procured from Tanzania, the DRC, Kenya and Somalia.

The GI-TOC has investigated these reports, which suggest three routes for weapons smuggling. First, and most surprisingly, sources in Niassa linked to the insurgency reported that during the al-Shabaab occupation of Mocímboa da Praia, weapons and logistics equipment were flown into the town using fixed-wing aircraft. Other sources also reported that aircraft had been flying into insurgent-occupied Mocímboa da Praia, suggesting that this route was being used to bring in foreign fighters from Somalia and other countries for strategic discussions with the Mozambican insurgents.

Despite there being multiple separate reports of aircraft landing in Mocímboa da Praia, it has not been possible for the GI-TOC to conclusively confirm this information.

Small fixed-wing aircraft are widely used along the east African coast, and with a willing pilot and a false flight plan it could be possible to travel undetected to Mocímboa da Praia. The kind of radar systems required to identify these low-flying aircraft do not exist in northern Cabo Delgado. However, it is difficult to imagine that this activity would have gone unnoticed, whether within pilot circles or from the ground. It is also possible that this narrative is being used to keep other trafficking routes concealed.

The second possibility is for weapons to be smuggled overland, via Malawi, or over the more remote border posts into Niassa. This could include weapons sourced in conflict areas in eastern DRC, transported via Lake Tanganyika, which is known as an active smuggling route for a variety of goods including ivory and weapons. This would replicate suspected weapon smuggling routes existing at the height of elephant poaching in Niassa Reserve.

Border posts along these land borders are known for extracting corrupt payments to move goods such as gems, gold, timber, bushmeat and, in the past, ivory. However, it has not been possible to independently confirm that these routes have been used to smuggle weapons to al-Shabaab.

Third, weapons may have been moved via seagoing dhows south from Tanzania to insurgent-held territory along the Mozambican coast. In late 2020 and early 2021, basic supplies (such as food items) were being transported into Mocímboa da Praia from southern Tanzania (around Mtwara) at night to avoid helicopter fire from DAG. This may also have been used as an arms smuggling route, as reported in GI-TOC interviews conducted in 2020. However, it has not been possible to confirm that weapons have been moved along this route.

Interestingly, drones were reported to have been captured from al-Shabaab insurgents by the Mozambican military for the first time in March 2022. Images of one of these drones (shared by the Israeli company, MTech, who supplied the Mozambican forces with signal jamming technology used to capture the drone) show a small device of the kind widely commercially available internationally, which the insurgents would have used for reconnaissance.

Disruption of trafficking routes due to the insurgency

Our research consistently found that trafficking routes through northern Mozambique have changed in the face of the region’s increasingly unstable security situation. Changes include routes having shifted away from areas where insurgents hold territory and conflict is most intense – drug trafficking landing sites, for example, have moved south to the southern Cabo Delgado and Nampula coastlines. Therefore, trafficking networks in northern Mozambique are unlikely to also be providing weapons to al-Shabaab.

While there may be some international flows of arms that have reached al-Shabaab (including the recently captured reconnaissance drones), the evidence suggests that the volume of these flows would nevertheless pale in comparison to the number of weapons sourced from Mozambique’s military, either via conflict or through corruption. DM

This article draws from a new research report from the GI-TOC, “Insurgency, illicit markets and corruption: The Cabo Delgado conflict and its regional implications”, funded by the Hanns Seidel Foundation, available at: https://globalinitiative.net/analysis/mozambique-cabo-delgado-conflict/

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

Comments - Please login in order to comment.