INFANT NUTRITION

WHO/Unicef report reveals how companies violate global standards in the marketing of formula milk to parents

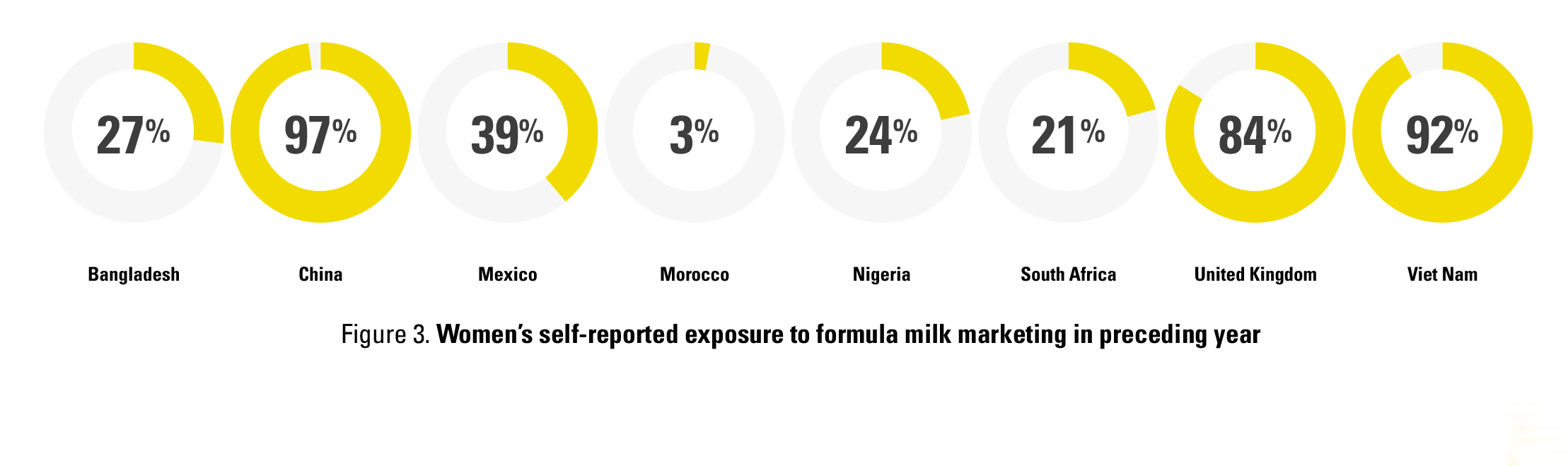

A landmark new report reflecting ‘the most complete picture to date’ of the marketing of formula milk to mothers and health professionals around the world, including in SA, says that 51% of parents and pregnant women have been targeted by companies that produce breast-milk substitutes, even though this violates international standards on infant feeding – and is illegal in SA.

The joint WHO/Unicef report, How marketing of formula milk influences our decisions on infant feeding, published today, is the first systematic, multicountry, multiregional study of formula-milk marketing, and the first to feature the voices of 8,500 women on their experiences.

The report highlights industry tactics to promote formula milk such as distorting scientific evidence to legitimise inaccurate health claims and push their product, systematic targeting of health professionals (on whom mothers rely most for health information) including incentives and gifts to get them to promote their products, and using manipulative marketing tactics – especially online and via the difficult-to-regulate social media – to exploit parents’ anxieties and aspirations.

“This research shows that formula milk marketing knows no limits,” says the report. “Forty years on, formula-milk marketing still represents one of the most underappreciated risks to infants’ and children’s health.”

This is because formula-milk feeding undermines breastfeeding, which the WHO and Unicef recommend for all babies where possible, including those of HIV-positive mothers: Ideally, babies should be breastfed within one hour of birth, then exclusively breastfed for their first six months – this means no water, no formula, or any other liquid or solid – with continued breastfeeding alongside the introduction of nutritious solid foods up to age two.

Breastfeeding reduces a range of health risks for both babies and mothers: It reduces young children’s illness and death from diarrhoea, pneumonia and malnutrition, reduces their risk of obesity, enhances their cognitive development, as well as reduces a mother’s risk of breast and ovarian cancer, diabetes and hypertension.

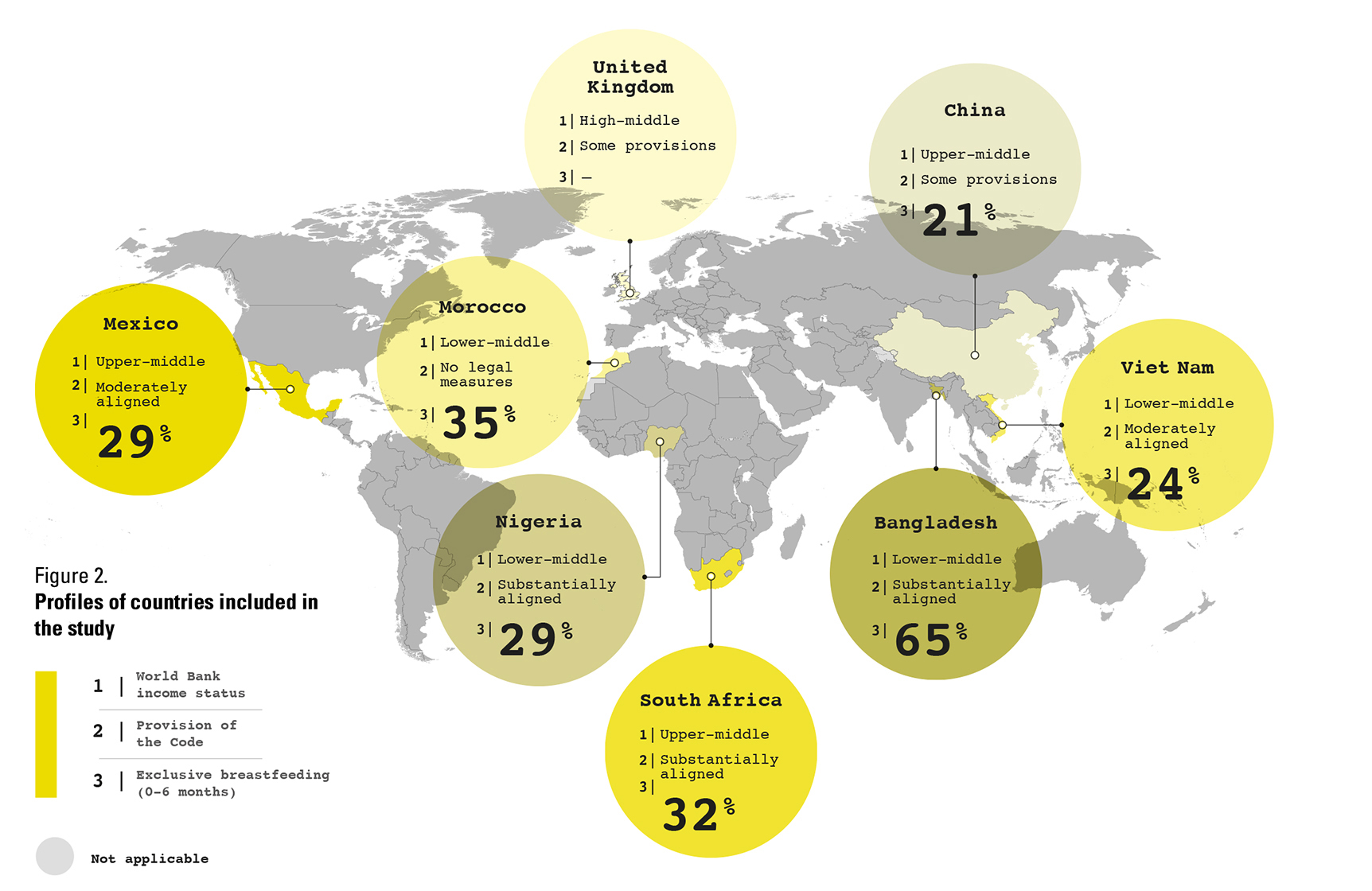

This first-ever systematic, multi-country, multi-regional study of formula-milk marketing draws on surveys and interviews carried out between 2019 and 2021, with 8,500 women and 300 health professionals in cities in South Africa, Bangladesh, China, Mexico, Morocco, Nigeria, the United Kingdom and Vietnam.

Just over half (51%) of the mothers and pregnant women report being targeted by formula-milk marketing, despite the existence of the WHO’s International Code of Marketing of Breast-milk Substitutes (the Code). The Code, designed to protect parents from aggressive marketing practices used by the baby-food industry, was adopted in 1981, when the World Health Assembly approved it (118 countries voted in favour; only the US voted against).

South Africa was among 136 countries that ultimately translated that agreement into national legislation to make the Code legally binding within their countries. South Africa’s law is called R991 and aims to protect and promote breastfeeding by regulating the inappropriate marketing of breast-milk substitutes for children aged 0-3 years, removing “commercial pressures”, “conflicts of interest” and “perverse incentives” from the infant-feeding arena.

And yet, the report says, the industry’s marketing around the world remains “pervasive, personalized, and powerful”.

“These marketing practices just blatantly disregard the recommendations and agreements of the World Health Assembly (WHA),” says Nigel Rollins, a WHO scientist and the lead researcher on the report, in an exclusive interview with Maverick Citizen.

“It’s a fundamental human rights issue,” Rollins said, calling out the “prevalence, invasiveness, and unrelenting nature of marketing” designed to influence the environments in which decisions are taken – by mothers and fathers – at one of the most vulnerable times in a parent’s life. It compromises both the right to parents’ impartial decision-making based on accurate information and the right to a child’s health enshrined in the UN Convention of the Rights of the Child.

Acknowledging that we are all bombarded with marketing for all kinds of products at every turn, Rollins said that what makes formula-milk marketing different is the $55-billion per year industry’s cynical exploitation of parents’ hopes and aspirations.

“If anything in life captures what human society is about,” Rollins said, “and what our vision and future is for our society, it’s the first years after the birth of a baby – and what industry is saying is, ‘Here’s a commercial opportunity.’ That somehow puts the marketing and the strategic exploitation of that moment into a different space than any other type of marketing.”

The WHO acknowledges that cultural, psychological and socioeconomic factors also drive low rates of breastfeeding.

“This is not an attempt to remove formula milks from the shelves of supermarkets,” he said. “WHO is not calling for any limiting of access to formula milk by families and mothers – or to limit the rights and decision-making of women. Some women need formula, some choose it for a range of reasons, and it is their right to do so. What we are highlighting is the marketing practices that seek to influence the environment in which decisions are made, and those decisions impact on the health and development of children, no matter whether it’s a high-, middle- or low-income setting.”

Enforcement – or lack of…

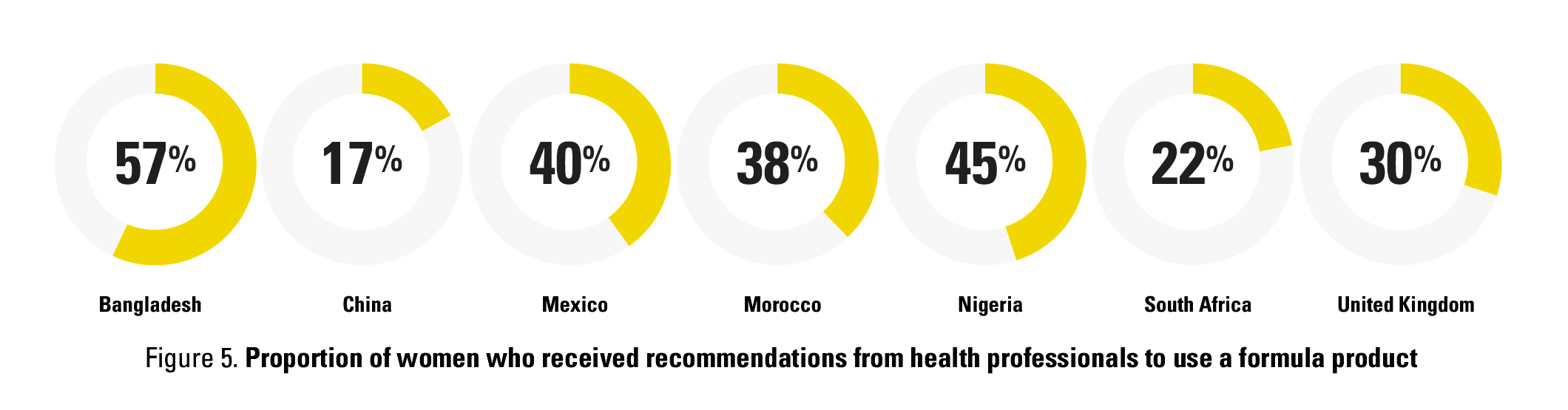

Clearly, violations are frequent and flagrant, and the challenge is around enforcement. The WHO says that “large numbers of health workers in all countries had been approached by the baby feeding industry to influence their recommendations to new mothers through promotional gifts, free samples, funding for research, paid meetings, events and conferences, even commissions from sales, directly impacting parents’ feeding choices”.

And yet, says Rollins, “In no country has there been an example of a meaningful sanction. You’ve got to ask the question, why don’t we have meaningful sanctions even when there’s strong legislation?”

In South Africa, says Tanya Doherty, professor in the Health Systems Research Unit at the South African Medical Research Council (SAMRC), “We have the Code legislated but we have very weak enforcement – there’s one person at the National Department of Health who’s responsible for Code compliance, which translates into no penalties against violators, even when health professionals or civil society report violations.”

South Africa is one country whose R991 is highly praised by the WHO, and yet of the 40 public and private health professionals in South Africa interviewed for this research, less than half (19) had ever heard of R991.

Still, Doherty says, “There’s no way a [marketing] representative could walk into any public sector hospital and try and market formula, whereas it’s completely rampant in the private sector.”

Doherty was an adviser to the WHO on the South Africa component of the research behind the report, which was carried out in Cape Town and Johannesburg, using a survey of 300 pregnant women and 750 mothers (1,050 people of the 8,500 total), focus group discussions with women, marketing diaries kept by women, and interviews with health workers – 17 from the public sector and 23 from the private sector.

Doherty told Maverick Citizen that in South Africa, health workers were reported by women to be a major source of trusted advice on feeding, second to family members, yet they were also the main people giving advice on using formula and specific brands of formula.

So even though public-sector health workers were not reporting being reached by marketing in their place of work, Doherty said, “In fact, we saw the same beliefs around the advantages and benefits of formula coming from mothers and from health workers – they both had their perceptions influenced by these claims that are very clearly in the marketing messages, and on the tins themselves” – with terms used such as ‘gold’, ‘supreme’, ‘opti’, ‘superior’ and ‘human-milk oligosaccharides’.”

“Women would seek advice from health workers around issues like crying, sleeping, the equivalence of formula to breast milk after seeing ads for [milks] that claim to be equivalent to breast milk,” Doherty describes.

“And the health workers in this study firmly believed that companies have advanced so much in their production of formula that it is now equivalent to breast milk. That was shocking,” Doherty said, especially as this group was made up of nurses and doctors, including paediatricians.

Clearly, these strategies have paid off for the formula-milk industry, which globally spends $3-billion to $5-billion per annum (5-10% of annual turnover) on its marketing, “because it works”, Rollins said. The report states that “multiple studies have shown marketing’s ability to increase demand and consumption, including for unhealthy products such as tobacco, alcohol, and ultra-processed foods”.

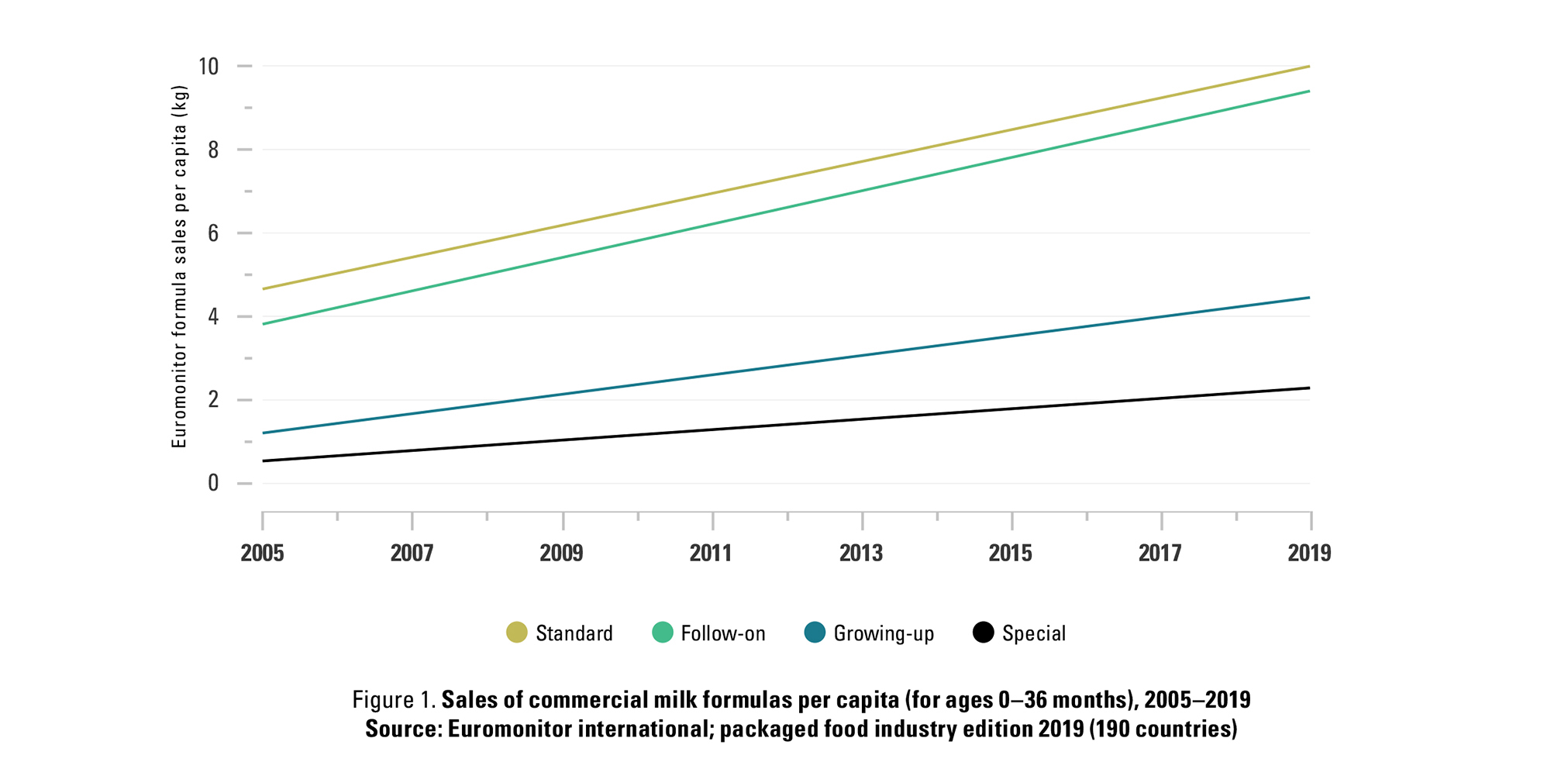

Rates of breastfeeding have increased very little in the past 20 years, the WHO says – globally, 44% of babies under six months old are exclusively breastfed – while sales of formula milk have roughly doubled over the same period.

Only 32% of babies under six months are exclusively breastfed in South Africa, which has seen a steady growth in infant-formula sales over the past 15 years, Doherty and others wrote in the South African Medical Journal in 2019, “from a retail value of R1-billion in 2004 to R4.2-billion in 2018 (a 33.3% per capita increase) and a forecast of over R6-billion in 2023.”

The Lancet 2016 Breastfeeding Series estimated that higher rates of breastfeeding could have averted 823,000 deaths in 75 low- and middle-income countries in 2015, and prevented 72% of hospital admissions for diarrhoea. Because formula is expensive, and clean water and bottle sterilisation are often not accessible, formula feeding can be dangerous, causing disease from bacteria, and malnutrition from formula that has been “stretched” by dilution.

The report’s conclusion that women’s confidence in breastfeeding is undermined by insidious formula-milk marketing tactics seems to apply equally in South Africa, including “a sustained flow of misleading marketing messages,” the WHO says, that reinforce myths such as the “necessity” of formula in the first few days after birth, the inadequacy of breast milk’s nutritiousness, or that the quality of breast milk declines over time.

Also, Doherty told Maverick Citizen, “Formula is seen as a solution to any breastfeeding problems. Just as much as in the private sector, public-sector health workers were saying, ‘You’re having trouble? It’s time to introduce formula’. There was no sense [among the interviewees] that if you provided good lactation counselling that this could overcome a challenge. It was an easy solution that a health worker could say, ‘You’ve got a crying baby? This is the one you need for that’.”

In understaffed and pressurised hospitals, it’s also a function of facilities, staff and workload. “It’s far quicker to suggest something that can be mixed up in five minutes, that doesn’t take an hour to sit and provide support and counselling,” Doherty said.

Doherty said that 51% of pregnant women in South Africa said they wished to breastfeed exclusively, exactly the same proportion as the average of the other seven countries, but the second-lowest among the eight countries surveyed (lowest was Morocco at 49%, highest was Bangladesh at 98%).

Yet in South Africa, only one-third (32%) of 0-5-month-old babies were breast-fed in 2016 (the latest data available). And this comes off a low base: from 7-8% in 2003. The very low rates in the early 2000s have been partly attributed to the government’s HIV-prevention measure of providing free formula in public clinics, which may have had an unhealthy side effect for HIV-negative women, too. (In South Africa, one in every five women is living with HIV.)

In 2011, when the WHO established that exclusive breastfeeding for at least six months was safe and preferred for the babies of women living with HIV, the government stopped providing free formula, and breastfeeding rates started to rise. But we still rank 36 out of 51 African countries, and our 31.6% falls far short of the UN Decade of Action on Nutrition’s target of at least 50% of babies (everywhere) to be breastfed by 2025.

Digital marketing: A priority

Crucially, digital marketing, which has a long-term impact on mothers’ beliefs about formula milks, must be tackled, the report says. Data are gathered and used in sophisticated ways to target and reach out to women, often through individual interactions with “influencers”.

“Influencers target and reach out to women, and nobody knows the provenance of those messages,” Rollins says, “whether the influencers are being funded, and by whom. And then you have a whole set of options through chat rooms where industry reps are then reaching out on an individual basis: ‘Send me your email and we can have a discussion offline’ – which is just completely wrong. It’s explicitly called out in the Code.”

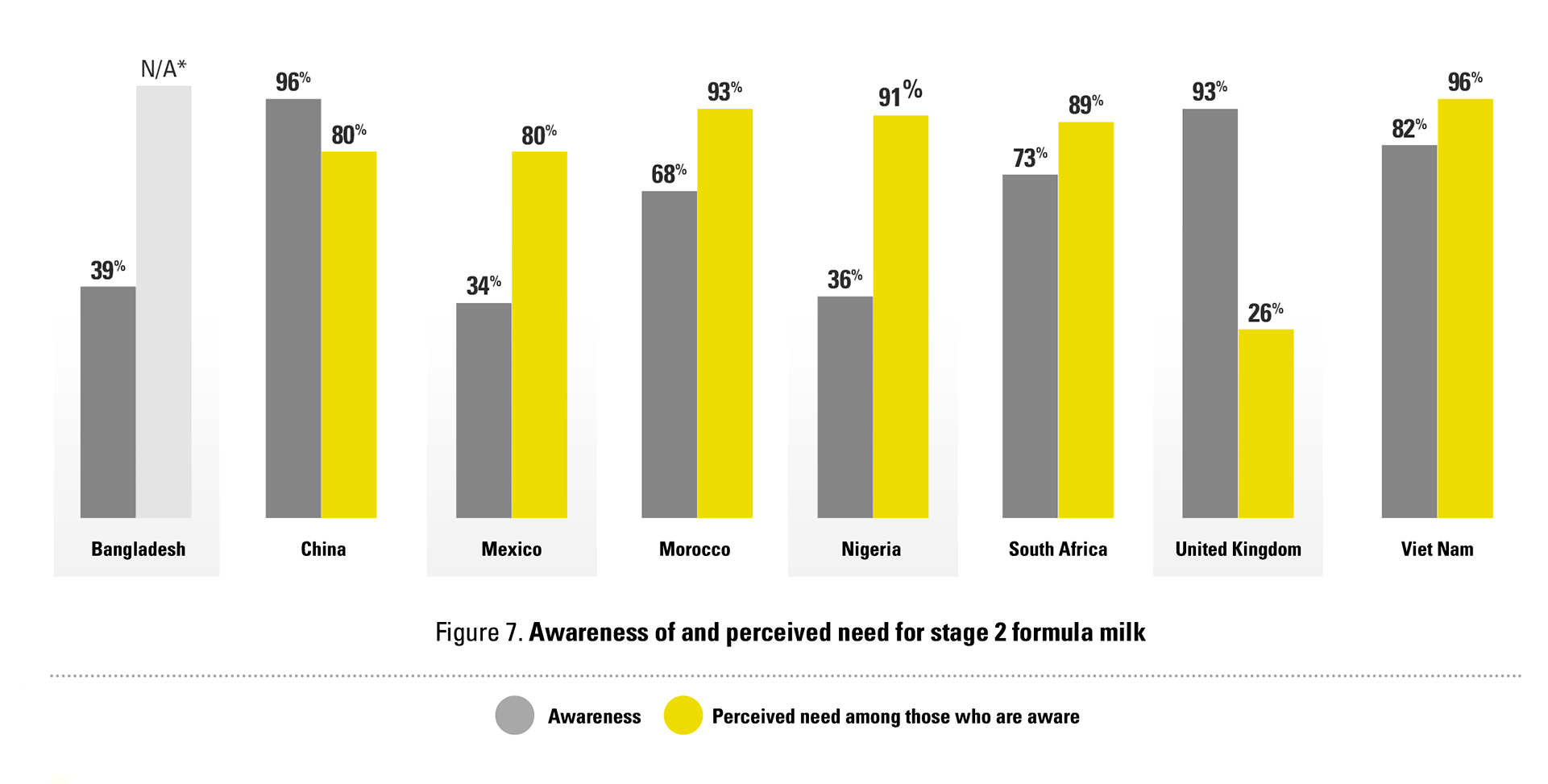

Rollins emphasised that this report is about the way in which marketing is influencing values. “We now see formula milk as the norm,” Rollins said, because of all of society’s shifts in norms and values. “We don’t need follow-on milks – WHO doesn’t recommend them, health-professional associations don’t recommend them, and yet doctors and families often believe that they are actually necessary. We’ve been gradually nudged and nudged to believe that is true.”

Calls to action?

The WHO cannot mandate member states to take action, so the report outlines “opportunities for action” to mitigate the unethical marketing of formula milk (there is not yet a special treaty such as the WHO’s Framework Convention on Tobacco Control) and to try to create environments that support women and parents in their child-feeding decisions.

The suggested actions are high-level and non-specific, given the different contexts in which countries need to act. They include encouraging countries to pass laws regulating marketing, to monitor and enforce the laws, to prevent false “scientific” claims, and to safeguard children’s health on digital platforms, as well as encouraging health professionals and their associations to strengthen conflict-of-interest policies.

“What is the responsibility internationally of these huge global brands who have clearly made a decision not to align with the Code?” Rollins asks, also suggesting that investors – banks and pension funds – insist on companies’ alignment with public-health guidelines.

“Invest in mothers from a national government side,” Rollins explains, referring to strengthening maternity-related protections and support, “and disinvest from companies that fail to align with the Code.”

Another crucial element to get right, Rollins said, is the need for much better regulation – globally – on formula-milk product development.

“There shouldn’t be any health claims, anyway,” Rollins said, “but you get industry highlighting the addition of this ingredient or that ingredient – such as these ‘human oligosaccharides’, things that are important for brain development. If these are beneficial for one child they should be there for every child.

“Product development should be scrutinised to the same level as pharmaceutical development and you shouldn’t have differential formulas. If you have one ingredient [for which] there is some belief that it has value, then it should be in every formula. It shouldn’t become a marketing ploy where they say, ‘we’re adding this, and if you can pay more for it then your baby’s going to be brighter’. First, the information is untrue, and second, there needs to be equity – this shouldn’t be used as a pricing strategy.”

Perhaps most crucially, the report calls for a comprehensive review of “the entire digital ecosystem – including data capture, data brokering and content dissemination” using “a public health lens”. The report urges that governments together with international authorities “develop enforceable regulations that protect child health and development from harmful commercial marketing”.

The WHO has started to work on this, Rollins says, having taken a decision at its governing body level to set in motion exactly such a process.

“Public health has got to understand the issue,” he emphasises. “This clearly dovetails with a whole set of other areas where digital marketing is also a problem.” This would mean that digital marketing of other harmful products, such as sugary drinks, fast food and other ultra-processed foods, could fall under the same recommended regulations.

Why now?

“I think we realised that our understanding of marketing was very superficial,” Rollins told Maverick Citizen. “We didn’t piece together the political influences, we didn’t see the lobbying by the dairy industry, we didn’t join the dots between those political activities and the way in which guidelines are developed.”

Because the WHO is the UN organisation that has responsibility for health, Rollins said, one of its core functions is to synthesise the evidence and provide guidance.

“So as we reflected we said, we need to do this more comprehensively. There is a process that is absolutely needed that spans issues of human rights, health, understanding digital, and that clearly goes beyond the skills and expert basis of WHO,” Rollins said, “but WHO can convene a process.” The timeline for this work is notionally two years but could take longer, Rollins believes.

“It’s a bit like a jigsaw puzzle – and hopefully the pieces will come together to give us a much better understanding around the problem, the scale, and to drive urgency. It’s a bit like a frog in hot water – we have been in the water and just gently warmed up, but we haven’t even recognised the scale of it, and the impact that it is having on child health and development.”

Rollins is careful to point out that this report should not be viewed as criticism of governments or of health professionals.

“We need to say, how do we work together to go forward – because the problem is not the government, or the health professionals or the individuals or civil society. The problem is the readiness of the industry to adopt marketing practices that are manipulative, highly funded and partial.” DM/MC

Adèle Sulcas writes about food, health and science. She worked previously at the World Health Organization, at the Global Fund to Fight Aids, TB and Malaria, and is the former editor of the Global Fund Observer.

[hearken id=”daily-maverick/9194″]

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

Comments - Please login in order to comment.