GREATER KRUGER AREA

The big fence: Historical divisions plague conservation efforts in South Africa

A ‘big war’ rages in southern Africa between those who can legally harvest natural resources and those who can’t, says environmental educator Vusi Tshabalala.

Conservationists must move beyond textbook knowledge if they are to address the conflict and historical divide created by protected areas.

So says Vusi Tshabalala who manages an environmental monitoring programme in one of southern Africa’s biggest biosphere regions. The Kruger to Canyons Biosphere Reserve covers 2.5 million hectares and includes two key tourism sites – the Kruger National Park and the Blyde River Canyon, as well as an international floral hotspot, the Wolkberg region. More than two million people live in or near these extensive conservation areas.

Tshabalala completed a national diploma in nature conservation in 2010, but reckons the book learning he acquired cannot compare with the lessons he has learnt from engaging directly with people in rural communities in and around the Greater Limpopo Transfrontier Conservation Area.

Vusi Tshabalala, a presenter at a Khetha journalism training workshop held in Skukuza, in the Kruger National Park, in October 2021. Organised by WWF-SA, WESSA and Roving Reporters, the workshop explored the broader context of the illegal wildlife trade. (Photo: Vincent Shacks)

He referred to a rhino awareness campaign, visiting communities, talking about the importance of rhinos and the need to conserve them.

Tough questions

“At one meeting, an old man stood up and asked: ‘Really, what is the importance of this animal? The only thing it does is eat grass and poo. What’s the worst thing that can happen if it gets finished?’ ” recalled Tshabalala.

“We answered: ‘It’s part of the Big Five [lion, leopard, rhino, elephant and buffalo]’. The man replied: ‘Five is just a number. If we go down to four, so what? If you love five so much, why don’t you replace the rhino with the hippo? It’s bigger and more aggressive.’

“We waxed on about tourists coming to South Africa to see rhino and how this helps the economy, brings in a lot of money and all that. The man stopped us again,” said Tshabalala.

“He asked: ‘Who are the tourists coming to? They are not coming to me. All that money ends up in the reserves. I don’t get anything. I still go to bed hungry, without even a loaf of bread. This economic empowerment you are talking about; I am not feeling it; I am not seeing it; I am not benefiting from that thing being alive.’

“So, we said: ‘No, no, no, wait a bit. We also want to preserve rhino for future generations.’ ”

Tshabalala had hoped that tapping into feelings of customary heritage would finally settle the debate. It didn’t.

‘Who has even seen a rhino?’

‘So, why should we care if rhinos are wiped out?’ That might seem an easy question for a conservationist to answer, but environmental educator Vusi Tshabalala had to do some head-scratching when he faced this and a barrage of other tough questions during a meeting with people living near the Kruger National Park. They told him they did not benefit from the park, had never ventured inside it, and only four of them had ever seen a rhino. (Photo: Alexandra Howard)

Another old man stood up, animated and angry. “He asked: ‘Out of all you guys here in this community, how many of you have seen a rhino?’ There were 42 people. Only four raised their hands,” said Tshabalala.

“Then another person turned around and asked: ‘What future generation are you talking about when the current generation has not interacted with it. We are living here. We have not seen it. We have not touched it. We have not come close to it. We are okay. Our kids will be okay. Really, what’s the worst thing that can happen?’

“I said: ‘Ja, but they have ecological importance.’ A young man immediately interjected. He said: ‘But wait, to have rhino is expensive because of anti-poaching [measures] and all that. There are many reserves that now don’t have rhino. They still have tourists coming in. Their bush and trees are still doing well, as well as all the grass animals eat. Ecologically the reserves are fine.’

Floored

“We did not know what to say. We had run out of answers,” said Tshabalala. “I learnt an important lesson that day. Every answer we had given them, I had learnt at school, at university and in an office working environment. None of it talked to their realities. We said we would come back.”

Head-scratching

The bust of Paul Kruger, president of the Transvaal Republic, stands near a main entrance to the national park that bears his name. Nearly 120 years after Oom Paul left office and a few years short of a century after the park was proclaimed, conservationists are still struggling to win support from many people in communities bordering the park. (Photo: Flickr)

In the days that followed, Tshabalala thought deeply about an appropriate answer to that question: “What is really the worst thing that can happen?”, especially when seen from the perspective of people in communities who have derived little benefit from protected parks and game reserves.

The darkest side of the illicit wildlife trade gave him the answer. Dangerous international networks have entered communities, and today wildlife and animal parts are trafficked much like illegal drugs, arms and even people.

“So, when I went back, I asked: ‘Where will it stop? When rhinos get finished, they are going to move on to something else, and something else, and something else. Just like rhinos, people living with albinism get killed for the muti trade, and kids for their private parts. Who will be next?’

“Guess what? It worked,” said Tshabalala. People related to concerns that a criminal gang culture has emerged in communities, that gangsters have become role models for children who say: ‘Why go to school for 13 years when this guy, over just two weeks, can get a nice big car?’”

Hunters

Tshabalala also mentioned lively debates he has had about bushmeat poaching and legal hunting.

Officially, he said, a legal hunter was someone with a permit, granting him the right to kill an animal on a game reserve, either for the pot or for a trophy. More often than not these private reserves are on land that people from neighbouring communities consider part of their heritage, places where their forebears once hunted freely.

If such a person happened upon a porcupine on a road outside a reserve and killed it for meat, that person would be classified as a poacher, said Tshabalala. Yet owners of game reserves could kill any animal on their properties provided it was not a protected species.

“So, people see a great disparity between what a ranch owner can do, and what they are not allowed to do,” said Tshabalala.

Tshabalala also does not subscribe to the term “subsistence poacher” when referring to a person who kills an animal to feed his family.

“Poachers are criminals and traditional hunters are providers,” said Tshabalala.

Feeding families

Two residents of KwaNibela in northern KwaZulu-Natal rest on a self-built boat at the edge of Lake St Lucia. They sell fish and mats made of grass drawn from the lake at a market in nearby Hluhluwe. (Photo: Nomfundo Xolo)

“So we have commercial poachers, who are criminals, and traditional hunters, who are not criminals,” said Tshabalala. He believes that those who hunt to feed families should be given more legal opportunities to do so, especially in game reserves and protected parks where culling takes place.

He said this issue came to the fore on a reconnaissance to map out the Sabi area in Mozambique as part of an expansion plan for the Great Limpopo Transfrontier Park.

People there live in deep bush close to the park and depend on game for food, said Tshabalala. If you push them out, it will spark a never-ending cycle of conflict of the kind that has marred the conservation landscape in southern Africa ever since protected areas were declared, he said.

He mentioned a discussion he had with an old man who has survived from hunting in the Sabi area his whole life.

“There is a fence between me and the duiker I used to hunt,” the man told Tshabalala. “That is the only thing that stops me. I can get around the fence, or wait for it to get out the fence, then I can kill it. But even when it comes out, and I kill it, I am seen as a poacher.”

“Basically, at the end of the day, there is a resource that belongs to all of us,” said Tshabalala. “But it is only allowed to certain people, those who have money, who are educated enough to go to the department to get a permit and to go through all those processes. And then there is the villager, a hunter, who has not been taught about all these processes, and who, anyway, does not have money to pay for a permit.”

“So, there is a big war, a big fence, between who can and who can’t,” said Tshabalala.

‘Contested illegality’

He said behaviour defined as illegal by authorities, was frequently not viewed as bad or wrong by people living in or near conservation areas.

This issue of “contested illegality” extended way beyond the Great Limpopo Transfrontier Conservation Area, said Tshabalala, referring to the case of a KwaNibela fisherman, 25-year-old Thulani Mdluli, who is presumed dead after a clash with authorities on Lake St Lucia in the iSimangaliso World Heritage Site late last year.

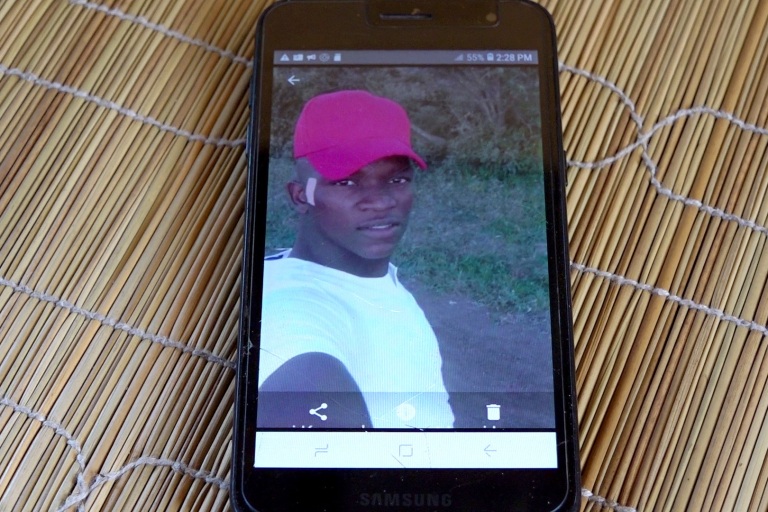

Thulani Mdluli, a 25-year-old KwaNibela fisherman has been missing since a 12 November clash with authorities last year. Rangers allegedly shot and killed Thulani’s brother, Celimpilo Mdluli, on 16 September 2020 while he was out fishing with two others on Lake St Lucia. His family want answers. (Photo: Nomfundo Xolo)

Tshabalala agreed that officially proclaimed protected areas and private game reserves were vital for conserving wildlife, but felt a more inclusive approach was needed.

To win the support of people who felt excluded, a new approach was needed. Community engagement, he said, must tap into realities that define people’s existence – the real stuff of life not found in textbooks. DM

Supported by USAID; the joint WWF-SA, WESSA and Roving Reporters initiative assists aspiring journalists to report on the complexities of illegal wildlife trade in and around Greater Kruger.

[hearken id=”daily-maverick/9194″]

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

I know the area around KNP relatively well and fully understand the perspective of poor people who look at the relative abundance inside protected areas, as compared to their reality. What the author and others fail to address, however, is the effect of human population growth. When Kruger was established a 100 years ago, SA’s population was an estimated 7m people, which has since grown to more than 60m. The same natural resources now have to sustain almost 10 times the number of people it once did. If one considers the old Transkei where the only bird you’ll ever see is a crow, as well as the communal areas to the west of KNP, the overgrazing and complete destruction of the natural environment is heartbreaking. Small wonder then that the “traditional hunters” are laying claim to the protected areas… We can demand a “more inclusive approach” as much as we like, but if the number of mouths to feed continue to grow at the historical rate, no approach will ultimately be good enough.

Population growth and ‘we don’t care about tomorrow, I’m hungry now’ will render the KNP and other conservation areas a desolate wasteland within two generations, should surrounding communities be allowed free access to ‘food’.

“I am not benefiting from that thing being alive.” – the problem with South Africa in a sentence.