MEMORIAL

A giant and a father to all: Remembering and paying tribute to Dr Max Coleman

Late human rights activist Dr Max Coleman was like an eagle – quiet and meticulous – swooping down on apartheid security police to help thousands of South Africans detained without recourse.

“Dr Max was like an eagle; a watcher of the system, always watching for detained comrades not to be tortured, killed or to disappear,” said Constance Seoposengwe, a former anti-apartheid activist and now a member of Parliament for the ANC. “He cared deeply for every activist from all parts of South Africa. He extended himself to serve those whose lives could be snatched by the cruel apartheid system, at any time.”

At a memorial service on Wednesday, 9 February, flanked by proteas and eucalyptus branches, Seoposengwe addressed struggle veterans, the Coleman family and journalists at the Centre for the Book in Cape Town. Coleman passed away in his sleep on 16 January at the age of 95.

Seoposengwe recalled travelling by train from her hometown of Kimberley to Johannesburg, through the night, arriving at Park Station in Hillbrow at 6am. At Khotso House on De Villiers Street, a liberation hub at the time, Coleman and his wife, Audrey, would welcome her – and others – with warm tea. Seoposengwe relayed how she was jailed and tortured while pregnant at the age of 22, in 1987. After escaping, it was to Khotso House that she fled. To the Colemans.

Max and Audrey Coleman at a Kagiso Trust function in 2011. (Photo: Kagiso Trust and Family)

“It is so overwhelming to talk about this giant, a giant called Max Coleman,” said Seoposengwe. “Yes, he was a father to his children, but he was a father to us, too. When I saw the news about his passing, I felt the same pain I felt when my mother died. Because that man, the humble Max Coleman, was a father to us indeed. He didn’t have to love us. He didn’t have to take care of us, but he did it anyway.”

Coleman and Audrey founded the Detainees’ Parents Support Committee [DPSC] in 1981 after their son Keith, then a student activist, was detained at John Vorster Square in Johannesburg. At the time, the pair stepped away from prosperous business interests to kick-start the DPSC, which would come to support thousands of South Africans held in jails without recourse. The committee provided legal help to detainees, petitioned on street corners, and shipped takkies, clean clothes and food parcels to people in jails, often detained without being put on trial.

In 1985, Coleman co-founded poverty-fighting agency Kagiso Trust, with the likes of the late Archbishop Emeritus Desmond Tutu and the late Dr Beyers Naudé.

At the memorial service on Wednesday, Kagiso Trust chairperson Mankone Ntsaba said Audrey had insisted that the programme should not be sad, but a celebration of her late husband’s life.

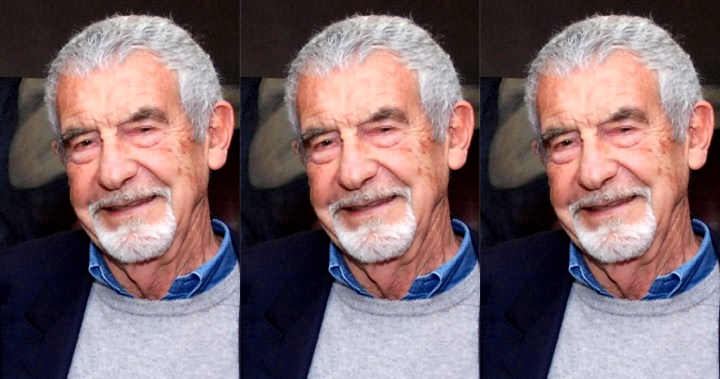

Dr Max Coleman in 1988. (Photo: Kagiso Trust and Family)

In a long blue dress, Audrey sat at the front of the hall, head tilted up at the pulpit. Several speakers attested to Coleman’s devotion to his “beautiful wife”, as he referred to her until the very end. She had been his role model, and certainly not “the woman behind the man”. Coleman and Audrey, who had been together for 70 years, marched side-by-side, said their peers. The couple had four sons: Brian, Neil, Keith and Colin.

At the service, Coleman’s grandson, Miles, recalled how his grandfather’s idea of dressing up had been khaki shorts and takkies. His grandfather enjoyed bird watching and scuba diving, and would retell his sightings in nature in great detail, Miles said.

Another grandson, Sam, played an elegy to Coleman on a grand piano. Following the piano recital, Minister of Public Enterprises Pravin Gordhan got behind the pulpit, quipping: “I wish I could play the piano like that. I’m completely tone-deaf.”

Then Gordhan passed his condolences onto “Auntie Audrey” and the Coleman family, saying: “The establishment of the DPSC – in our case in Durban – was a formidable achievement. It made a huge difference to the thousands of detainees in solitary confinement, in mass cells during the emergencies of the mid-Eighties.”

With a tremor in his voice, Gordhan continued: “Above all [Uncle Max], I felt your presence in my police cells in each of my detentions, particularly during the passing – as Neil [Coleman] just reminded us – of Neil Aggett, at the hands of the security branch [Aggett, a doctor and trade union organiser, died during detention in 1982]… Those were indeed dark and fearsome days, the Seventies and Eighties. When we could get clean clothes, occasionally, or a packet of biscuits, maybe sweets and some of us got reading material, then we could see the impact of the work that you initiated.”

Behind Gordhan, Neil had taken off his mask as he wept, his brother Colin leaning closer to offer him a handkerchief.

Speaking from the pulpit, Coleman’s peers agreed: Coleman had been a man of few words – in fact, he barely spoke. He had been known for his meticulous notes, his exhaustive DPSC records kept in filing cabinets in his office, and his kindness.

Addressing the memorial service, human rights lawyer and activist Peter Harris read excerpts from his book Just Defiance, recalling a trip he and Coleman took to Lusaka in 1990, to take a legal statement from Vlakplaas commander Dirk Coetzee.

In the book, Harris describes Coleman: “Max is in his late sixties, a slim man with thinning hair and a pencil-thin moustache… I think it’s remarkable that he decided to get involved in resistance politics after years spent in the corporate world. His life took this course when two of his sons were detained for long periods in solitary confinement during the first two states of emergency. He gave up his profitable business and devoted himself full-time to helping detainees and doing other political work.”

In the book, Harris recalls their interview with Coetzee: “We sit down and Max and I take out our notebooks… As the day progresses and he [Coetzee] becomes more at ease, his language deteriorates badly. He swears venomously and with real passion, his face contorting, the words exploding from him. Sometimes when he swears, I see Max start and look at him with horror.

“Late at night in the small room, with the drink, the smoke and the swearing and the death, I feel we are clustered around that fire in the veld on which the body burns, the flesh sticking to our hands, the smell all about us. With each passing day, Max grows quieter in the interviews…”

To the memorial audience, Harris described Coleman as a man of moderation who didn’t smoke, didn’t swear, and barely drank. He relayed how, as Coetzee revealed increasingly gruesome details during that particular trip, Coleman would bend lower over his notebook, continuing to take meticulous notes.

Colin Coleman with his parents Max and Audrey Coleman at his 55th birthday party in Johannesburg on 28 October 2017. (Photo: Gallo Images / Sunday Times / John Liebenberg)

Leading the memorial service was Reverend Frank Chikane. “I would like to say what is normally not said among us,” he said. “That the involvement of ‘white’ comrades in the struggle, however small their number were, was critical for our victory against the apartheid system.

“We thank our late father Max Coleman, our mother Audrey Coleman and their sons, Brian, Neil, Keith and Colin, for their contributions to the struggle; the risks they took in solidarity with us. You humanised us. Our task now is to humanise South Africa by lifting the poor, who are mainly black, out of poverty, and to clean the corrupted system.”

In November, President Cyril Ramaphosa conferred the Order of Luthuli in Silver on Coleman and Audrey. Acknowledging the honour, in a statement the couple voiced distress over the “state capture and thuggery which have corrupted not only the state, but the minds and the soul of the ANC”.

In the statement the pair called on Ramaphosa to do more about unchecked corruption in South Africa: “We back President Cyril Ramaphosa’s efforts to cleanse the ANC. We back his efforts to modernise the state. But we urge him to do more.”

In the course of his tribute, Gordhan voiced similar sentiments. “The ultimate victims of these developments are not the people who sit in these SOEs [state-owned enterprises] or the various government institutions. But the ordinary people in our townships and rural areas, who wait for this government and its people to serve them better,” he said.

Wrapping up the service, a video recording showed Ramaphosa lauding Coleman’s contribution to a democratic South Africa and voicing condolences to the family. DM/MC

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

Comments - Please login in order to comment.