BOOK EXCERPT

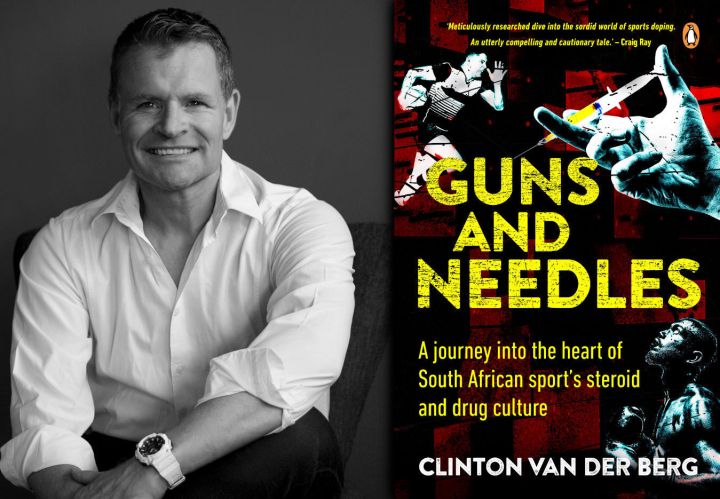

Guns and Needles by Clinton van der Berg: ‘Even the world-famous Comrades ultramarathon couldn’t avoid the doping cloud’

South Africa revels in its reputation as a sport-loving country. Yet just beneath the surface lurks a dark underbelly. In this excerpt from ‘Guns and Needles: A Journey into the heart of South African sport’s steroid and drug culture’, author Clinton van der Berg looks at the shadier history of the world’s largest and oldest ultramarathon.

Inevitably, perhaps, even the world-famous Comrades ultramarathon couldn’t avoid the doping cloud. In the hundred years that the epic race has been run, the biggest shock came in 2012, when champion Ludwick Mamabolo tested positive for methylhexaneamine, a nasal decongestant considered a stimulant.

The official ruling by SAIDS laid out the context of Mamabolo’s situation. “After 2005 no South African was to cross the finish line of Comrades in first place until 2012. On 3 June 2012 Mr Mamabolo – a South African – achieved that feat. In the days that followed Mr Mamabolo received the accolades due to a South African winner of a very prestigious event.”

Indeed, he was fêted everywhere he went. Two weeks later, however, Mamabolo heard from friends that there were problems with the urine sample he had provided at Comrades. He met with ASA the following day and was handed a letter addressed to him by SAIDS.

The grandson of Titus Mamabolo, a revered middle-distance athlete from the 1970s, young Ludwick was shocked when he learned of the finding, even more so when his B sample confirmed the first. It was suggested to Mamabolo that he should plead guilty – as he would consequently receive a lighter sanction – but he refused to do so.

Convinced that he had a case, prominent law firm Werksmans Attorneys volunteered to handle it on a pro bono basis. Opting for the courts was a first for South African athletics. In another twist, the Limpopo athlete was allowed to return to competitive running the following February – his only means of earning an income – pending the outcome.

On 2 May 2013, he was found not guilty in a fifty-eight-page judgment after facing a committee appointed by SAIDS. “They found there was a system failure in the Comrades doping process,” was attorney Trevor Boswell’s withering, if diplomatic, assessment. Multiple irregularities were identified. Part of the SAIDS ruling reads like a comedy, detailing an extraordinary sequence of events surrounding Mamabolo’s liquid intake both before, during and after the ultra-marathon. The rundown of events over the twenty-four or so critical hours surrounding the race certainly lent plausibility to Mamabolo’s denials. Part of the ruling read: “One of the supplements [to] which he added USN Anabolic Nitro X was not listed by him in the doping control form he signed after the race. This was due to tiredness on his part, but again the substance did not result in the finding.”

On race day, the report revealed, Mamabolo was frustrated when he arrived at the first reception station because the drinks that had been prepared were not available to him. He also did not receive his drinks at the next refreshment station, and it was only by the third that he was provided with his first drink.

“He recalled that somewhere after the halfway mark, when he was extremely thirsty, he obtained a drink from a fellow athlete. He said the drink had a salty taste and he spat it out. This athlete was also tested and the results were negative.” It was part soap opera, part real-life drama. Mamabolo crossed the finish line just after 11am and collapsed. He thinks he blacked out for a brief time. Of all the people to give Mamabolo a recovery drink, hulking Springbok rugby forward Bismarck du Plessis was an unlikely candidate. The Sharks hero handed him an Energade, which was open.

“Mamabolo’s recollection of the sequence of events thereafter was about as clear as one could expect of someone who had just run, and won, the Comrades,” said the report.

This detail was given sustenance from a highly influential quarter. Comrades legend and nine-time winner Bruce Fordyce explained in his affidavit that it would not take much imagination to appreciate that Mamabolo would have been mentally and physically exhausted. It was evident that the doping controls had been nowhere near as strict, or as correct, as they ought to have been. A damning chunk of the SAIDS report read as follows: “There was little – one hesitates to say “no” but that is perhaps the truth – control over the Doping Control Station as regards who entered it, when, the reasons for athletes leaving and returning (in at least one instance this occurred with an athlete being tested); and the record keeping in this regard was misleading and unhelpful to anyone seeking to understand what happened or perhaps investigated a particular concern.”

Mamabolo was praised as “an honest witness”. “The test results in respect of Mr Mamabolo are declared void,” concluded the report. Mamabolo, who had always proclaimed his innocence, pleaded in the aftermath for education, telling reporters, “Black people – I’m sorry to say it – do not have computers where we can log in. We wake up, eat pap, and train. But we have the right to be informed and it’s important to us. I assure you I’m not a drug addict. I do not smoke, and I have not had a drink my whole life.” Having won the down run, he soon switched his attention to the up run, which he vowed to win. Mere weeks after being exonerated by SAIDS, he finished fourth. He ran Comrades three more times, twice finishing second, but was unable to fully savour an unsullied win.

Mamabolo’s other misfortune was that his Comrades controversy coincided with social media, amplifying the news of his positive result and setting loose the online trolls. It ensured a difficult time for the elite runner.

Twenty years earlier, a similar doping fate had befallen the 1992 champion, Charl Mattheus, who became the first Comrades athlete to be stripped of his winner’s medal after testing positive. The newspapers had a field day, but at least he was spared being shamed on social media. Mattheus, who had grown up in Despatch, the same Eastern Cape town rugby coach Rassie Erasmus once called home, reportedly took an over-the-counter cold medicine for a sore throat, which contained phenylpropanolamine.

It was on the IAAF’s banned substance list. Mattheus’s problem was one of timing: soon after, the stimulant was removed from the IAAF’s list of banned substances. (Notwithstanding WADA not considering it a prohibited substance, it remains on the agency’s watch list to detect patterns of misuse in in-competition sport only.) Two years after losing his crown, Mattheus returned to run Comrades – he finished eleventh – and then, in 1997, he made history. After a thrilling three-way duel with Nick Bester and Zithulele Sinque, he crossed the line at Kingsmead Cricket Stadium in first place. He was thus the first champion to regain his title after being disqualified.

His winning time of 5:28:37 was emphatically faster than that of his first (5:42:34) and went some way to erasing the stain of 1992. “Hopefully now the people won’t talk about Charl Mattheus the 1992 winner who was disqualified, but Charl Mattheus the 1997 Comrades champion,” he beamed. Having trained in America for several years, Mattheus later moved to the US. He is now an assistant professor and internship programme coordinator at California State University. He still enjoys running.

The 1990s were certainly colourful for the country’s most famous race. A year after Mattheus’s triumph, Bellville runner Herman Matthee found a novel way to finish seventh: video evidence showed that he had caught a taxi along the route, cutting out almost 40 kilometres of the 90 kilometre race.

But no one could match the ingenuity of the twin brothers from QwaQwa in the Free State, Fika and Sergio Motsoeneng. In 1999, the pair ran the race as a relay, popping into a portable toilet at the 44 kilometre mark for Sergio to remove his transponder, shirt, bib, hat and shoes to hand to his well-rested brother, who continued the race.

Former winner Nick Bester, who finished fifteenth, voiced his suspicions, having not sighted Sergio along the way. Race officials then examined the time sheets and cleared Sergio. The jig was up, however, when the Afrikaans daily Beeld published two juxtaposed images of Sergio running. Trouble was, he was wearing his watch on opposite arms and had mysteriously grown a scar on his left shin.

Both brothers were banned from competing in ultra-marathons for 10 years, later reduced to five, and Sergio had to return the prize money he had earned for finishing in the top 10. He cited poverty as their reason for cheating. Sergio’s inherent talent was plain to see when he returned to race Comrades in 2010. He finished third and pocketed R90,000 for doing so.

Shortly afterwards, however, he tested positive for nandrolone. It was an expensive deception – he had to forfeit his prize money and his gold medal.

The brothers were never heard from again. DM/ ML

Guns and Needles by Clinton van der Berg is published by Penguin Random House SA (R270). Visit The Reading List for South African book news – including excerpts! – daily.

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

Comments - Please login in order to comment.