OP-ED

Reflections of a Wayward Boy: The lows and highs of a scribe – from Pinochet’s Chile to Dr Seuss and Sir Edmund Hillary

Living and working in New Zealand in the 1970s revealed how an egalitarian myth can arise in a relatively affluent outpost of a global system. Yet the most profound effect on my outlook and thinking – especially regarding the role of journalism – came not from New Zealand, but as a result of a brief sojourn in post-coup Chile.

The first three years of our stay in New Zealand – a time of a jobs surplus and before the ongoing global economic downturn had begun – demolished for us the myth of that country’s egalitarianism and social democratic exceptionalism. The country seemed to me to be the epitome of an affluent garden suburb in a world city of gross inequality and often horrible repression.

But, living there, we also saw – and gratefully experienced – reasons for the persistence of that myth. Among these was dental care at schools, a liberal approach to formal education and, above all, an efficient, effective and free national health service. This also gave us a glimpse of what was possible; what a potential future could include.

And while self-satisfaction and a patronising racism was widespread, there were many who saw through the veneer of a successful social compact and, in different ways, were trying to create a truly sustainable and better future. They were part of several strong and growing anti-racist and radical groups dedicated, in a general sense, to trying to turn the egalitarian myth into reality.

Among them were the people who organised weekend training camps for anti-racist activists, challenged inequality at home and abroad, opposed the Vietnam War, nuclear testing and even brought over from the US the doyen of passive non-violent resistance, George Lakey, to train local trainers. However, on a personal level, 11 September 1973 was a watershed date: the day the popular unity government of Salvador Allende in Chile was overthrown in a military coup led by General Augusto Pinochet.

News of the coup came only weeks before the International Air Transport Association was scheduled to hold its conference in Auckland and where the Chilean national airline was represented by its newly appointed president, General Germán Stuardos. Interpreting for Stuardos was the local Lan Chile airline representative, Pepe Ibierta, who made no secret of his support for the ultranationalist Falange of Chile.

A leading local columnist, Bob Gilmour, who preceded me for a scheduled 10-minute, one-on-one interview with Stuardos, looked grim when he emerged and muttered about “bloody tinpot fascists”. Within minutes I understood Gilmour’s reaction: Ibierta was deliberately distorting the responses of Stuardos, a smoothly diplomatic Christian Democrat supporter of the coup.

My always limited and grammatically appalling Spanish was quite rusty, but I managed to conduct – to the obvious anger of Ibierta – what became a near hour-long interview that culminated in Stuardos ordering the Lan Chile rep to provide me with a free return ticket to “see for yourself” in Chile.

Ibierta subsequently gave me an open ticket, pointing out with a smirk that Lan Chile only flew from Tahiti, an extremely expensive flight away from Auckland. He knew that I had by then established a small media collective that was successful, but certainly not in the league to afford flights to French Polynesia. However, I was able to do a deal with a local travel magazine that offered discounted advertising to airlines in exchange for air miles. I got first-class return air fares to Tahiti in exchange for promising three feature articles.

Then the second of three potential snags struck: after the Sunday Herald closed down, I established the Aotea News Feature Service. It expanded rapidly and, without considering the distinction between profit sharing and managerial control, I made fully equal partners of the two journalists I had recruited: they voted against me going to Chile. So once again, I packed up my gear and left. This time from the media centre we had founded only months earlier.

The third snag came when I arrived in Tahiti: the officials in the Lan Chile office informed me that there were no seats available on any of the twice-weekly flights to Santiago. I was desperate, so, although I had no idea how to contact General Stuardos, I said I wanted to use the office telephone to contact the airline’s president who had personally invited me to Chile. There were hurried consultations followed by an apology: economy class seats were all taken, but I could be accommodated in first class.

It was a useful lesson and one of many insights gained over the weeks spent in the horrible sadness of a beautiful country wracked by violent repression and hyperinflation. When I arrived in Santiago in December 1973, the Chilean currency, the peso, had collapsed and exchanged at more than 1,000 to the US dollar. A stay in a good hotel cost me just $3 a day.

Fear and, even more so, desperation, seemed to permeate everything. But, with the aid of a Canadian Catholic priest I managed to get into the sprawling detention camp where suspected foreign radicals were held; counted the disproportionate number of new graves in the cemetery since the coup; heard the clatter of helicopters heading out to sea at night over Valparaiso and listened to the tales of fisher folk about the bodies caught up in their nets.

Then, naively, I filed, through the Reuters office in Santiago, some copy for The Observer in London about the situation. That was before I discovered that all such correspondence also went through to a special newsroom in the junta headquarters. From “real journalists” who were still nominally employed by the La Segunda and El Mercurio newspapers, I heard that this newsroom was staffed mainly by Falange supporters. They wrote all the news that was deemed fit to print and that appeared in each edition of the daily publications.

Then my visit was abruptly curtailed. A well-dressed man, speaking impeccable English, called to tell me that there was only one seat left on the Wednesday flight to Tahiti. “I can always take the next flight,” I said. To which he answered, very calmly: “Perhaps there will never be another seat.” I got the message and left that Wednesday.

Back in New Zealand, after writing the promised travel features – on Tahiti and on Rapa Nui (Easter Island), a Lan Chile stopover on the way to Santiago – I briefly turned my back on journalism and worked on construction sites. But, with a labour shortage keeping the “social compact” in place, there were plenty of opportunities and jobs for generally decent pay, were plentiful.

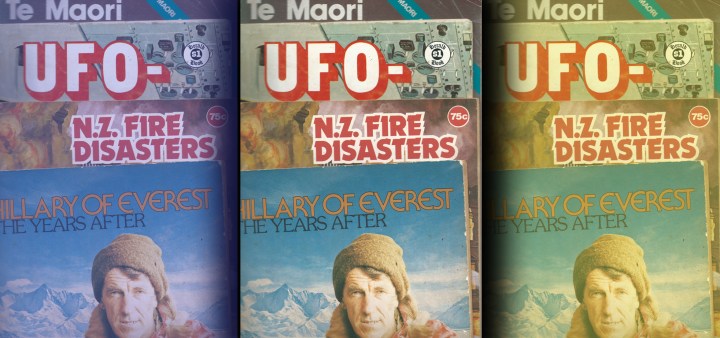

On a volunteer basis I went on to teach at, and chair, a state-subsidised experimental primary school, worked at a remedial reading clinic and spent a lucrative but unsatisfying year in public relations. There was also some talk-show radio hosting; researching and writing the whakapapa (genealogy) of the Ngati Whatua people for Te Maori magazine, producing one biography, a variety of textbook chapters, three magazine-format “dollar books” and a number of magazine profiles while working mainly as a freelance sub-editor.

Along the way I met and spent time with some incredibly impressive individuals such as Ed Hillary of Everest fame and his family, and, on the broad educational front, the polymath, Ivan Illich, best known for his book, Deschooling Society, as well as Theodor Seuss Geisel, better known as Dr Seuss. At the same time, it seemed the anti-apartheid movement was starting to win the battle to halt racist tours. But the fightback in South Africa still seemed to be stalled (another example of faulty analysis: this was 1976).

As a family, we felt we should take the time to get to know this geographically stunning country and more of its people before heading back to Africa. So I bought an old school bus, roughly rigged it out as a mobile home, and signed a contract to provide photo features to the country’s then most widely read magazine, NZ Women’s Weekly. It also meant we would get to know, and deal, with one of the greatest pioneer distance learning institutions, the New Zealand Correspondence School, known, since 2009, simply as Te Kura (The School). DM

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

Comments - Please login in order to comment.