‘Bridget?” the doctor calls.

Bridget McNulty rises from her chair in the waiting area and steps into the examination room. Her head is throbbing and the headache only adds to the fuzziness in her brain.

Workwise, the past year has been a dream for the 25-year-old: She’d started her first job at a glossy magazine in downtown Cape Town and published her debut novel.

Her health, however, has been a nightmare.

“I’d lost more than 10 kilos and looked skeletal,” McNulty remembers. “I was permanently exhausted, eating huge amounts of food, desperately thirsty, waking up in the night to pee…”

Still, she wasn’t entirely sure that all this was cause for concern.

“I just assumed this is what being a ‘grown-up’ was all about — you get a full-time job and you’re just constantly exhausted.”

Inside the exam room, the doctor comes to an astonishing conclusion about her mysterious weight loss.

“He suggested that I was eating too healthy,” McNulty says.“That didn’t seem right but I was relieved it wasn’t something like, I don’t know, diabetes.”

But just to be sure, the doctor pricks McNulty’s finger, placing a single blood drop on a small testing strip and inserting it into a glucometer — a handheld device used to measure blood sugar levels.

The machine’s digital screen flashes the number “26.” McNulty’s blood sugar level is roughly double the recommended range. High enough to, without treatment, lead to possibly fatal complications.

Still, the doctor tells her to come back tomorrow for more tests.

“He sent me off into the city,” McNulty says.

“The last thing he said to me was to eat junk food,” she continues. “I went to Steers and had a burger and chips because I thought it would make me feel better.”

In less than 24 hours, she would be in an intensive care unit.

What’s for dinner: Calories, chemicals and profits

(Video: Pexels)

For centuries, humans have processed foods, sometimes to make them edible and sometimes to preserve them. But since the 1950s, companies have increasingly turned to a more extreme form of processing. Here, firms use industrial methods to physically and chemically transform foods like wheat, soy or corn into cheap, ready-to-eat and highly profitable ultra-processed foods.

Globally, ultra-processed foods are driving epidemics of diseases such as obesity, diabetes and hypertension, warns Carlos Augusto Monteiro, professor of Nutrition and Public Health at the University of Sao Paulo in a July edition of the British Medical Journal.

“Some types of food processing contribute to healthful diets,” he writes, “others do the opposite.”

Three large research reviews show that eating large amounts of ultra-processed food puts you at risk of developing — for instance — obesity and type 2 diabetes, a condition in which your body can no longer regulate levels of blood sugar, also called glucose, Monteiro cautions. It’s also thought to increase your risk of cerebrovascular problems or issues with blood flow to the brain that can lead to strokes.

And this may not just be because ultra-processed food is packed with calories.

Emerging research suggests chemicals in ultra-processed foods may, for example, interfere with the signals our bodies use to tell our brains that we’re full after a meal. Similarly, substances used in packaging may leach into our food, disrupting the way our bodies regulate hormones, including those associated with reproductive health.

/file/dailymaverick/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/MC-FrontOfPackageLabel-Laura_2-Graph1.jpg)

Almost 80% of packaged food on South African supermarket shelves may be ultra-processed

Ultra-processed food is flooding South African supermarkets — but you might not know it.

In a survey of almost 7,000 packaged foods and beverages on the shelves of major South African supermarkets, almost eight out of 10 foods were ultra-processed, found a July study published in the journal Nutrients.

Today, companies in South Africa have to tell the ingredients in the food you buy — they don’t legally have to tell you how much of these ingredients are in the food you eat, although many do. Meanwhile, most of us either don’t read or fully understand what is on food labels that do exist, at least a decade of research shows.

Almost 10 years ago, the South African National Health Department proposed legislation to introduce not only mandatory nutrition labelling but also front of package labels. Almost three dozen countries around the world use some form of front of package labels to help shoppers quickly identify packaged foods that are high in sugar, fat and salt, for example.

New local research shows that a simple black and white warning label — similar to that used in many Latin American countries — could help South Africans quickly identify foods high in sugar, saturated fat and salt, many of which are likely ultra-processed.

It may also push companies to make healthier products.

‘All the signs were there, but I didn't know them’

Cape Town dreaming: Bridget McNulty was supposed to be celebrating in the Mother City with her first job in publishing at a glossy magazine – and a debut novel to boot. So why was her health a nightmare? (Drone footage: Pexels)

In Cape Town, McNulty is still feeling wretched the morning after her doctor’s visit. She rings a friend, who happens to be living with diabetes, for advice.

“Should I be eating? Should I not be eating?” she asks after recounting her blood sugar results from the day before.

“Don’t eat anything,” he demands over the phone, “I’m coming right over.”

McNulty’s friend arrives with his glucometer, which reveals McNulty’s blood sugar is now so high that the machine can’t read it.

He bundles her into the car and rushes her to the hospital where she is diagnosed with type 1 diabetes, a condition in which the body often suddenly begins to attack the cells that produce the hormone insulin that regulates blood sugar levels. Science is still working to unpack why. In contrast, type 2 diabetes is when the body has stopped responding to insulin.

“In retrospect, of course it was diabetes,” McNulty says, “all the signs were there, but I didn’t know them.”

After spending five days in the intensive care unit, she is discharged from hospital with stacks of information on diabetes — and how to change her diet to help control it.

She says: “I had never read a food label in my life.”

Cornflakes or bran: So you think you can… read a label?

/file/dailymaverick/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/MC-FrontOfPackageLabel-Laura_1.jpg)

In Johannesburg, the two-story Centre for Diabetes and Endocrinology (CDE) lies nestled between the busy M1 highway and the leafy suburb of Houghton Estate — just 15 minutes’ drive from the centre of town.

Inside, people living with diabetes sit waiting to see specialist doctors, or queue at the pharmacy to collect medication. Just down the hall in her office, dietician Vhonani Mufamadi is surrounded by empty food yoghurt containers, old margarine tubs and the occasional powdered drink mix.

“Most people come in thinking that they know how to read a label,” she says with a gentle smile, “but they don’t.”

Multiple studies from across South Africa show Mufamadi’s patients are not alone: Many if not most South Africans don’t regularly read nutrition labels. If they do, it’s most likely to happen if people are buying a new product for the first time or if they have a chronic health condition they are trying to manage, suggested a 2018 study in the International Journal of Consumer Studies.

What looks like trash surrounding Mufamadi’s desk at first glance is actually a curated collection of food labels that she uses as teaching aids.

Her favourite may be the bran flakes.

She grabs a brown box from the shelf behind her and turns to set it on her desk before reaching for a canary yellow carton that once contained cornflakes.

“Labels can be difficult,” Mufamadi explains, placing the two packages side by side to reveal their labels as she does when counselling patients, “that’s why you want to just start with one, two or maybe three items on a label to look at.”

The cornflakes lists less sugar per serving than the bran, she explains.

“Many people would think they should choose the cornflakes.”

But Mufamadi cautions, the body converts carbohydrates into sugar, meaning that high-carb foods too will push blood sugar levels up just like plain sugar. Although lower in sugar, the cornflakes’ high carb count makes it a worse choice than the bran cereal although a bowl of oats would be better, explains the CDE’s latest cookbook.

Some people will see Mufamadi for only one session, others need more follow up.

“It’s about baby steps.”

Kitchen nightmares: Why no two food labels look the same… in South Africa

/file/dailymaverick/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/MC-FrontOfPackageLabel-Laura_3-Graph2.jpg)

South Africans may have a harder time with food labels than most given that companies aren’t required to include them on foods. As a result, South Africa is faced with a plethora of nutritional labels — none of which are very easy to read.

In May 2014, the national health department proposed amending the country’s 1972 Foodstuffs, Cosmetics and Disinfectants Act to require nutritional labels on the back of products. These regulations would also provide for food manufacturers to volunteer to place front of package labels on food.

The type of labels the health department initially suggested have been widely criticised by experts at both the World Health Organization and Pan American Health Organization (PAHO), who say it largely replicates complex information that in most places already appears on the back of foodstuffs.

But since a front of package label was first proposed, moves to roll it out in South Africa have stalled for nearly a decade.

Health department spokesperson Foster Mohale says the delay was partly to allow South African researchers time to carry out the studies needed to understand what should be on a warning label and what type of label would work best. Mohale confirmed to Maverick Citizen that the National Health Department has now finalised revisions to the proposed front of package labelling legislation. The department’s legal team is now reviewing more than 200 pages of technical inputs before new proposals are gazetted for public comment.

In the meantime, much of the long-awaited local research on front food labels has been published in the last year, including studies on what front of package labels should warn consumers about it and what they should look like.

Here are the four things scientists say to look for in your food

Tamryn Frank is a nutrition researcher at the University of the Western Cape. In 2018, she and a team of scientists surveyed almost 7,000 packaged foods and beverages on the shelves of large, South African supermarkets to get a sense of what foods South Africans were eating.

“We went down every single aisle and photographed every single packaged food item with a nutrition label on it,” Frank explains.

Frank found that almost eight out of 10 packaged foods surveyed were ultra-processed. The same could be said for 60% of beverages they recorded.

Then, she and her team mapped patterns of diseases in the country and what drives them: For instance, high blood pressure is driven partly by high salt intake and killed almost 20,000 people in South Africa in 2017, the most recent national death statistics show.

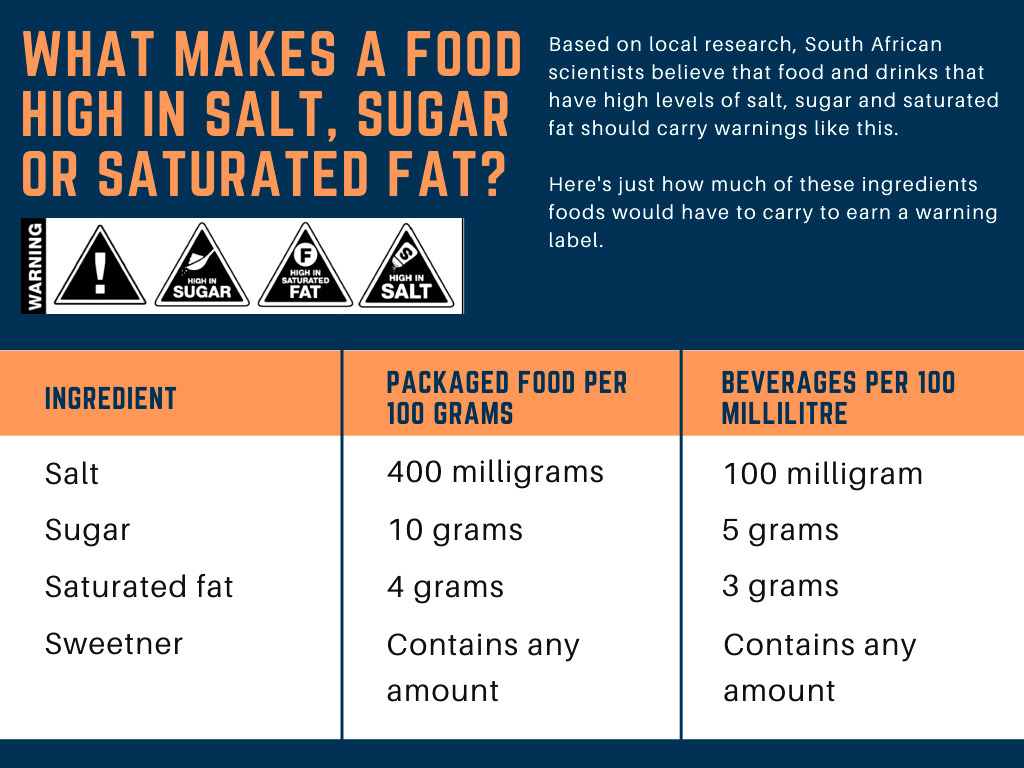

Based on these findings published in August in the journal Nutrients, Frank and her team have proposed that if South Africans wanted to make better choices at the till to avoid falling sick, they needed to know at least four things about their food:

Whether it contained high levels of added sugar, salt or saturated fat — and if food or drink contained any non-sugar sweetener.

Scientists still can’t say for sure whether the use of sweeteners leads to better health in the long term, including slimmer waistlines or healthier teeth, shows a 2019 research review published in the British Medical Journal. Researchers warn that there’s also not enough available information to rule out that sugar-substitutes could come with potential harms.

“From a proactive point of view — and based on what’s happening elsewhere,” Frank explains, “we thought it would be sensible to include non-sugar sweeteners in our model.”

Ultimately, Frank’s study recommended against warning labels for trans fat after finding that 2011 legislation aimed at limiting trans fats in processed foods had largely been successful. In contrast, Frank says the country’s sodium restrictions are too limited in scope to have done the same for a wide range of packaged food.

Caution, bad food ahead

/file/dailymaverick/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/MC-FrontOfPackageLabel-Laura_5-Graph4.jpg)

Countries around the world use one of roughly six different types of front package labels used globally but not all labels are created equal, warn agencies including the World Health Organization in a 2020 report. Uruguay, Chile, Peru and Mexico employ what the WHO calls front of package “warning labels”: Simple, black signs that use icons and minimal words to warn consumers about high levels of fat, calories or sugar, for example.

Unlike other front of package types, warning labels don’t include numbers — like how many grams of fat something contains or what percentage of your recommended daily calorie intake.

Instead, they simply tell consumers if there’s too much of something in a food — and that’s why WHO experts say these types of labels are the “best fit” for front of package labels.

South African researchers chose to test different versions of this type of warning label to see which worked best locally. To do that, University of Limpopo lecturer Makoma Bopape put different variations of food warning labels to focus groups in cities, villages and small towns in Gauteng, Western Cape and KwaZulu-Natal. Bopape showed these groups warning labels in different shapes, colours, sizes and fonts.

“We wanted to identify a system that would be easily understandable to everyone, irrespective of the age, education or literacy level,” she tells Maverick Citizen. “Research shows that if you use pictures and icons, people are able to relate to the meaning of those, unlike if one uses numbers or texts because they are difficult to interpret.”

Ultimately, showed the September study published in PLOS One, South Africans liked their food warning labels like they like their road signs: Stark, triangular and with a small picture of the danger ahead.

/file/dailymaverick/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/MC-FrontOfPackageLabel-Laura_6-Graph5.jpg)

Bopape and others are now in the process of publishing research showing that this type of warning sign outperforms “traffic light” models locally.

“There’s a perception that front of package labelling is only meant for people who have chronic conditions,” she says. “These labels are meant to be used by everyone because we need to prevent these conditions,” she says, “Once they have developed, they’re a burden on that individual and also the healthcare system.”

By 2030, South Africa’s public health will spend an estimated R35-billion to care for people living with at least one form of diabetes — this figure is more than half of the current National Health Department’s budget.

‘I smiled because I felt like I had a plan, I felt like I was going to be okay’

It’s been more than 14 years since Bridget McNulty was diagnosed with type 1 diabetes — and a lot’s changed. She’s started a diabetes non-profit, Sweet Life, that advocates around diabetes.

She’s also given up riding a scooter.

“I saw the light,” she jokes.

And she says her first trip to a dietician after her diagnosis inspired her to help simplify nutrition for others living with the condition. Today, Sweet Life is working with the National Health Department to create an almost entirely picture-based guide to eating for people living with diabetes.

“After being in hospital, they sent me home with a stack of pamphlets, leaflets and reading materials — it was so depressing,” she remembers. “Then, I spent an hour with a dietician and at the end of it, I smiled.”

“My mom said it was the first time I’d smiled in a week,” she continues, “and I smiled because I felt like I had a plan, I felt like I was going to be okay.” DM/MC

[hearken id="daily-maverick/9041"]

Almost a decade of research shows that few of us read food labels or understand them. (Photo: Jack Sparrow, Pexels)

Almost a decade of research shows that few of us read food labels or understand them. (Photo: Jack Sparrow, Pexels)