BHEKISISA CENTRE FOR HEALTH JOURNALISM

A few pills a day could keep severe Covid-19 away

Two drugs to treat Covid-19 have recently become available. These aren’t substitutes for a vaccine, but they could help at-risk people from developing severe disease. Here’s what you need to know about the new pills.

South Africa could see a Covid pill hitting pharmacy shelves before the end of the year. Drug manufacturer Cipla has begun making molnupiravir, a treatment that can lower the chance of people falling seriously ill or dying from Covid.

Molnupiravir, originally developed by pharmaceutical company Merck, has already received emergency approval for use in Covid patients in the US and the UK. Cipla is one of several applicants awaiting approval from the South African Health Products Regulatory Authority (Sahpra), the country’s medical regulator.

Because Merck has deals with other manufacturing companies, molnupiravir can be produced affordably. These cheaper versions of the pills are called generics because they aren’t sold under a brand name, although they have the same main ingredient and work in the same way.

Think of it this way: Panado is the branded name of a painkiller, but the ingredient that creates the actual effect is called paracetamol. In the same way, Merck’s drug, molnupiravir, is named for its active ingredient (the stuff that makes the pills work). By allowing other manufacturers to also make pills containing molnupiravir, the treatment can be produced and sold for less.

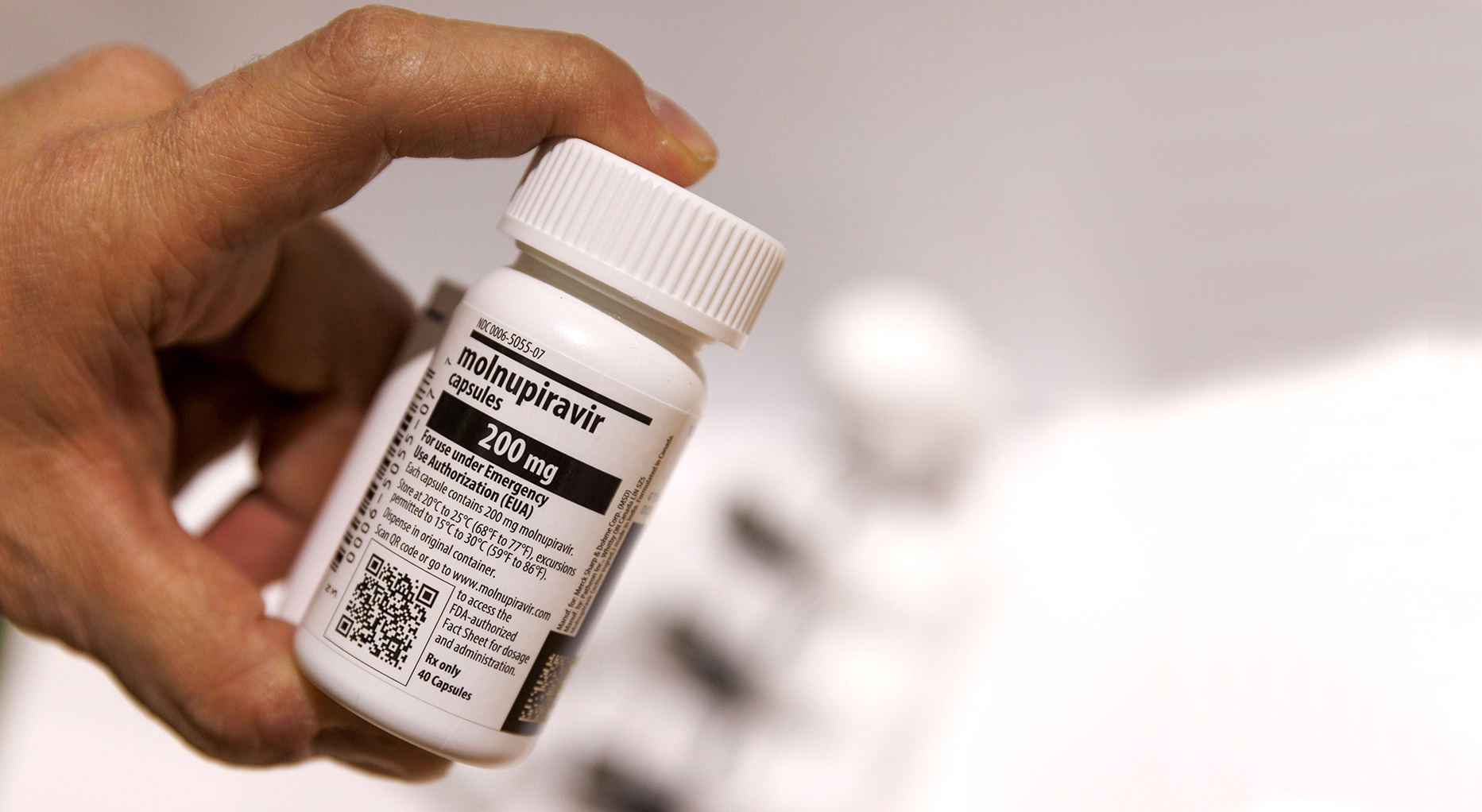

A worker handles a bottle of Merck and Ridgeback Biotherapeutics’ Molnupiravir antiviral medication. (Photo: Kobi Wolf / Bloomberg via Getty Images)

When it comes to Covid pills, molnupiravir isn’t the only option. Pfizer too has developed a treatment, called Paxlovid. These pills work slightly differently from molnupiravir but also lower someone’s chances of ending up in hospital from Covid.

Paxlovid is the brand name of the pill owned by Pfizer. It means that another manufacturer can’t sell a tablet with the active ingredients nirmatrelvir and ritonavir under the same name.

But as Pfizer has not made the recipe for mixing these ingredients together public, it would be difficult for another company to make generic versions of the drug (as can be done in the case of molnupiravir). This pushes up the price of Paxlovid, with a single pill costing around R270 in the US.

A full course of the Paxlovid treatment is 30 pills, so it would cost about R8,100 to treat one person — which would be unaffordable for most people in South Africa.

A full course of Merck’s molnupiravir is 40 tablets. An October 2021 analysis showed that an Indian manufacturer could produce a generic version of this treatment at R6.50 per pill, with a retail price of around R7.50 to allow for a mark-up and taxes. A full course of 40 generic molnupiravir tablets at this price would then cost around R300 — that’s 25 times less than Paxlovid to treat one person.

So how do these pills work and why do we need them if we already have vaccines? We break this down in the first of a two-part series.

Why would we need a pill if there’s a vaccine?

Existing Covid jabs are great at protecting you from severe disease, but they’re not foolproof. And with new variants likely to develop, as we’ve already seen with Delta and Omicron, there’s always a chance that the virus could sneak past the body’s defences and infect someone, even if they’re immunised.

And although Covid jabs are much better at protecting us against falling seriously ill with Covid than they are at preventing us from getting infected, they’re not perfect with this either. There are, for instance, some people, such as those who are 60 years and older or people living with comorbidities such as diabetes or obesity, who are much more likely to get very sick with Covid than younger people or those without comorbidities.

So Covid drugs don’t replace vaccines, but instead are an addition to the world’s medicine cupboard to help us manage the disease — because SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes Covid-19, is probably here to stay.

Both molnupiravir and Paxlovid are antiviral treatments, which means they work by stopping the virus from replicating in your body once you’ve been infected. The pills are taken early on after infection and rather than trying to kill off the virus (like vaccines get your immune system to do), they stop it from spreading through your body. In this way, the pills lower your chances of becoming so ill that you might die or end up in hospital.

In the case of breakthrough infections after being vaccinated, the pills could therefore be a great backup. For people who are especially vulnerable they could be a lifesaver.

New variants are less likely to sidestep the treatment because the drugs jam the virus’s copy machine rather than launching an attack against the germ’s structure, as happens with a vaccine.

On top of that, the pills can be self-administered soon after symptoms start and prevent severe disease from developing. So, theoretically, people could get a prescription for the drugs once they test positive, and then take the tablets at home, which will give them a good chance of recovering without being treated in hospital.

How do the pills work?

An antiviral drug can stop a virus from replicating in different ways.

Molnupiravir muddles with the genetic material of SARS-CoV-2 directly. The medicine confuses the virus while it’s copying itself because the drug’s chemical structure looks similar to that of a molecule the virus needs in the copying process.

But because it’s not exactly the right thing, the virus’s genetic material is put together in the wrong way. This eventually causes so many errors that there later are no more functional copies of the virus to go around, and it dies out. In short, molnupiravir causes the virus to mutate to death.

Paxlovid works differently. It’s a protease inhibitor, which stops a type of enzyme (called a protease) in the virus from working. When the protease doesn’t work, the virus cannot package itself into an effective little bullet that can move out of one cell, travel to another and then easily enter that new cell to start the replication cycle again.

So, whereas molnupiravir overwrites the genetic code of the virus and stops it from making functional copies of itself in already infected cells, Paxlovid disrupts the virus’s ability to infect new cells and keep on replicating.

How well do the pills work?

Molnupiravir reduces the risk of hospitalisation by 30% in high-risk Covid patients who are unvaccinated. And although the pills reduce someone’s chance of ending up in hospital with Covid by only 30%, it drops their risk of dying from the disease much more — 89%.

The research, among people of 60 years and older or those with comorbidities (such as cancer, heart problems, chronic kidney or lung disease or obesity), showed that molnupiravir was equally effective, regardless of the type of SARS-CoV-2 variant they had been infected with.

On 14 December, Pfizer announced that Paxlovid lowers a person’s chances of falling severely ill with Covid by 88% if they take a full course within three to five days of showing symptoms. The results of Pfizer’s study have not yet been published, but the pharmaceutical company submitted the data to the US medicines regulator, the Food and Drug Administration, which approved it on 22 December.

The Pfizer trial included just over 2,000 unvaccinated Covid-positive adults who were at high risk of developing severe disease but who had not yet been hospitalised and compared them with a similar-sized group of patients who received a placebo, or dummy drug. No deaths were observed in the treatment group.

Is there a downside?

At the moment, supply is still very limited. As with vaccines, demand for the drugs is high and the manufacturing process takes time. People may also need a prescription to get them (as is the case in the US), so it won’t necessarily be as easy as simply asking a pharmacist to give you the pills over the counter.

Despite data from the trials showing that side effects from the treatments are mild, the pills may not be suitable for everyone. For example, the way in which molnupiravir works may make it unsuitable for pregnant women (although scientists need more information to say for sure).

One of the ingredients in Paxlovid, ritonavir, slows down your body’s ability to break down medications. This allows the pill’s other active ingredient, nirmatrelvir, to disrupt the replication process for longer. But this is a double-edged sword.

Why?

While one drug attacks the virus, the other one reduces how well your body responds to other medications.

In this way, the Pfizer pill could potentially interfere with more than 100 drugs, including some cancer pills, heart medications and blood thinners, either making them work less well or upping the chances of an unexpected side effect.

Since people with comorbidities are likely to be taking other medications, this may limit the number of people who could benefit from the very drug designed for them.

Doctors would need to assess whether these pills are the right choice for patients who are on other medications. In some cases, the effects of ritonavir on other drugs can be managed for the five days of the Covid treatment, but it would be best that a patient’s doctor makes that call.

While they’re not a one-size-fits-all solution and don’t replace vaccines, the tablets have an important place in our anti-Covid medicine chest. With about 90% of people in low-income countries still being unvaccinated, having access to drugs to treat symptoms after infection — like molnupiravir and Paxlovid — can be a game changer. DM/MC

Find out how manufacturing the pills works and why generics mean South Africa could get its own stash of the drugs soon in part two.

This story was produced by the Bhekisisa Centre for Health Journalism. Sign up for the newsletter.

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

Comments - Please login in order to comment.