FOOD JUSTICE

Can South Africa legislate its way out of its crushing ‘double burden’ of malnutrition and into a healthier ‘food democracy’? (Part Three)

Two government departments are working on new food-related legislation that will hopefully address the long delays in restricting the marketing of unhealthy foods to children. In Part Three of an investigation looking at how marketing influences unhealthy food choices by children and their parents — as well as its adverse impact on health — we examine what is likely to be in South Africa’s apparently ‘imminent’ new food regulations, what local and international experts say new regulations should contain, and why government regulations alone will not solve our bigger food-related health problems.

South Africa has astronomical rates of both over- and under-nutrition — what is known as a “double burden” of malnutrition.

One in eight children under the age of five are overweight or obese (13% — more than double the global average), while one in four children (27%) are stunted (5% — above the global average).

When it comes to protecting children’s rights to safe, adequate food and good health, South Africa is lagging far behind on two other fronts: international recommendations, and other countries taking strong action to tackle their nutrition crises.

While other countries with similar malnutrition (especially overnutrition) problems to South Africa (see sidebar below: Countries that restricted marketing to children) have introduced strict measures such as regulations requiring more user-friendly labelling to indicate high levels of added sugars, fats and salt, “healthy choice”-type logos and ratings, and restricting some forms of advertising, especially to children, South Africa is taking its time to do the same.

Our children’s increasing consumption of fast food as well as of ultra-processed foods (UPF) and drinks, such as chips, salty snacks, biscuits and sugary drinks, is a major contributing factor to overweight (a body mass index, or BMI, over 25) and obesity (a BMI over 30), which are already at horrifying levels and are still rising sharply, researchers say.

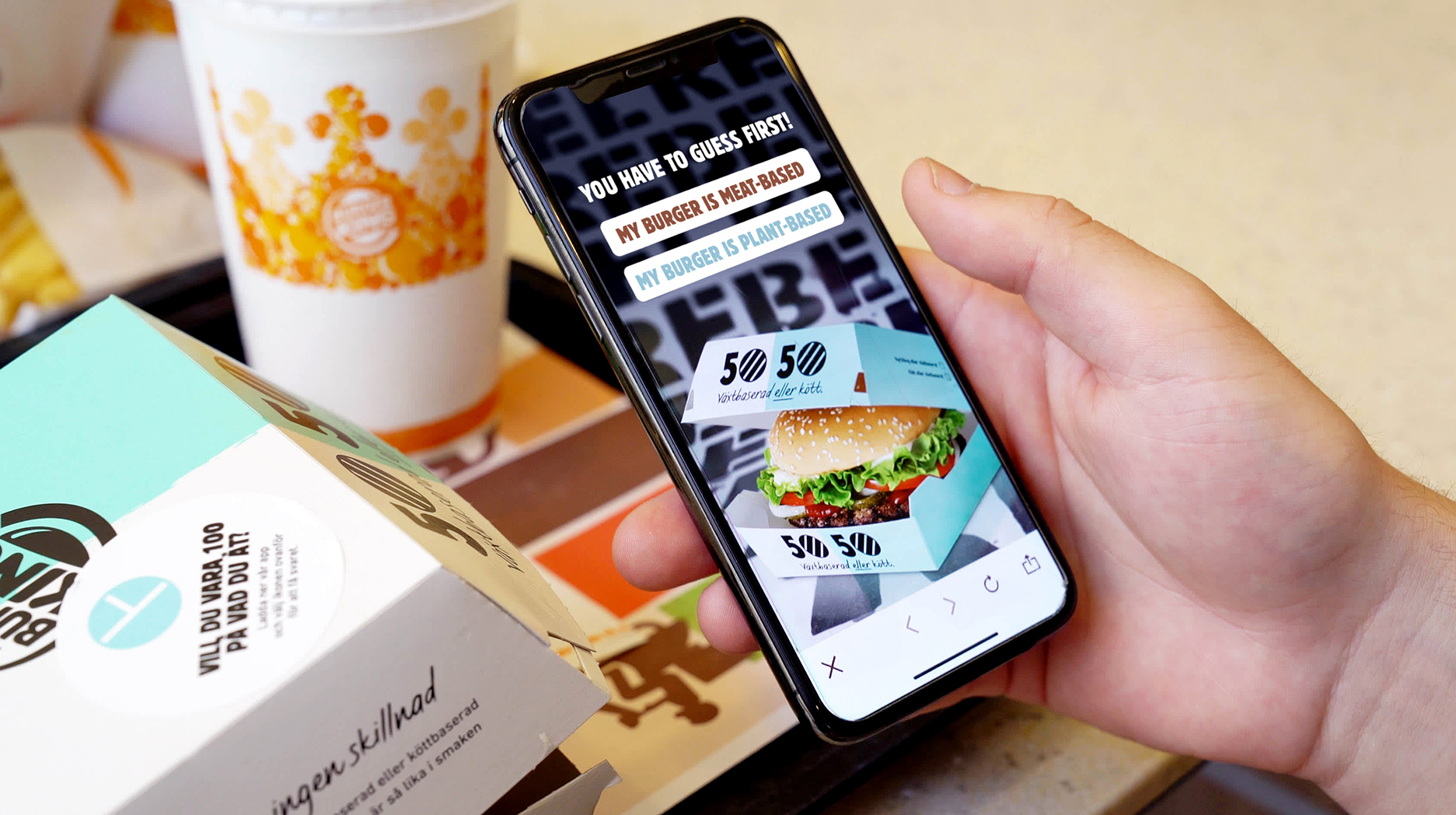

Globally, food marketing to children – especially via digital media such as social media platforms like YouTube, TikTok and Facebook – is increasingly seen by global health standard bearers as an infringement of children’s rights. (Photo: cnbc.com / Wikipedia)

Unregulated advertising and marketing, especially targeting children, is in turn a major contributing factor to the overconsumption of UPF — foods that have been transformed from their original form via industrial processes, including the addition of unhealthy fats, salt, ‘free’ sugars (all added sugars in any form as well as naturally occurring sugars whose structure has been broken down in processing), flavourants, colourants and other additives — which have recently been found to be addictive.

2014 amendment to SA regulations stopped in its tracks

It has been almost 12 years since the South African government published 2010’s Foodstuffs, Cosmetics and Disinfectants Act (R146), which addressed the labelling of food products (but not advertising or marketing).

In 2014, the National Department of Health began to tackle an amendment to R146, called R429, specifically to restrict the marketing of unhealthy food to children. The draft amendment was never passed into law.

In 2015, the Strategy for the Prevention and Control of Obesity in South Africa 2015-2020 included a similar focus on responsible and ethical marketing of food by the food industry. This strategy, spearheaded by the then health minister Dr Aaron Motsoaledi, went largely unnoticed — at least by the general public — and never reported any results after setting a target of a 10% reduction in obesity prevalence by 2020.

There has been no renewed anti-obesity strategy since (though one source says there is a new strategy-in-progress within the NDOH).

The lack of adequate government regulation of food marketing means that UPF- and fast-food producers — including overseas-based, transnational companies expanding their markets in the under-regulated Global South because their markets are shrinking in the increasingly regulated North — have recently penetrated developing country markets in insidious ways, altering cultural norms.

An advert for the Healthy Caribbean Coalition’s proposed front-of-pack (FOP) warning label system, featuring a black octagon that warns of a food product’s high sugar, sodium or saturated-fat content. The black octagon is the same symbol already used by Chile as a warning label in its highly successful FOP labelling system. It is not yet known whether South Africa will introduce a similar system as part of new regulations to restrict the advertising of unhealthy foods. (Photo: healthycaribbean.org/Wikipedia)

The publication Child Gauge 2020 says food producers have used “sophisticated marketing campaigns, supermarkets, fast food outlets and informal traders enabling sugar-sweetened beverages and ultra-processed foods to penetrate deep into informal settlements and rural communities, transforming both the local food environment and individual food preferences”.

These cheap, convenient and easily-accessible food (or food-like formulations) have become default choices for people — and notably parents — who are short on money, time and energy.

International standards and obligations

Globally, food marketing to children — especially via social media platforms like YouTube, TikTok, Facebook and more — is increasingly seen by global health standard-bearers as an infringement of children’s rights.

As far back as 2010, the World Health Organization issued a set of recommendations on restricting marketing and advertising of unhealthy foods to children, to guide countries’ efforts to design new policies or strengthen existing ones (see sidebar below: WHO’s CLICK monitoring framework).

Since then, the United Nations Committee on the Rights of the Child asked countries to “take all necessary, appropriate, and reasonable measures to prevent business enterprises from causing or contributing to abuses of children’s rights”. And a WHO-Europe December 2020 report says food marketing “has been unequivocally linked to children’s food preferences, requests, purchases and eating behaviours and hence to childhood obesity”.

In the 12 years since the WHO’s guidelines — and our now-inadequate R146 labelling guidelines — came out, countries such as Thailand, Chile, Ecuador, Indonesia, Mexico and Israel have introduced mandatory warning labels for products high in salt, sugar, fat and energy (others such as Australia and the EU have introduced other kinds of “healthy choice” logos or voluntary front-of-pack labelling laws).

Yet South Africa, whose double burden of malnutrition is severe compared to some countries that have acted on this, has still not demonstrated its seriousness in taking on this issue.

Among the countries that have restricted children’s exposure to unhealthy food marketing (see sidebar below: Examples of countries’ introduction of front-of-pack (FOP) labelling regulations), one of the most recent, reported in July 2021, was the United Kingdom’s announcement that it would ban all online junk-food advertising in an attempt to tackle its obesity crisis.

Another highly regarded example is Chile, which University of the Western Cape researcher Tamryn Frank cites as a country that has put effective regulations in place (in 2016), including warning labels on unhealthy foods, which are then not allowed to be advertised and not allowed in schools.

“It does seem to be having quite positive effects in terms of how the children are understanding and learning from that,” Frank said, “so it’s had an impact on the broader society, which I think warning labels on their own would not do. But [Chile’s policy] doesn’t address things like affordability of food, which in a country like ours is very important.”

So why is it taking South Africa so long to act?

The food marketing regulation that wasn’t

According to a non-government source (who did not want to be named for this article), the 2014 amendment “just sort of died”.

“What almost feels a bit mafia-esque is that it’s weird how no one can tell you what happened, or they refuse to tell you,” the source told Maverick Citizen.

The amendment was published, the source said, without prior informal consultation or attempts to build consensus among industry actors (such as Tiger Brands, Nestlé and other heavyweight members of the Consumer Goods Association of South Africa. The result was major industry pushback. Some food manufacturers allegedly complained that R429’s proposed new labelling system hadn’t been tested, and that more scientific evidence was needed.

Critics of the process surmise “industry interference”.

Others, such as Tamryn Frank, said that “given the nature of the comments, a decision was made to go back to the drawing board, to rework certain aspects” to strengthen the draft.

Frank explained that a Nutritional Profiling Model (NPM) was needed as a basis for restrictive food policies, so that the categories of “healthy” and “unhealthy” could be measurably defined. “It was crucial that the development of the NPM was evidence-based and followed a scientific process.” This has taken several years to complete.

Dr Chantell Witten of the University of the Free State, a child rights advocate and a co-author of the Child Gauge 2020, acknowledges the importance of the evidence-based approach as a basis for marketing restrictions, but is emphatic that regulation on its own will not make a dent in the on-the-ground crises of hunger and unhealthy eating that set children up for diseases and under-performing adulthood.

“What we really need to do is ask: What are the poorest 20% of people buying, and what can we do to make it better? Not slap a label on it — because that doesn’t change what they’re going to eat,” Witten declares.

Lori Lake, of the UCT Children’s Institute and another co-author of Child Gauge 2020, expands on this: “South African children are between a rock and a hard place,” Lake says.

“The slow violence of child malnutrition in South Africa has two forces acting on children: One is poverty and inequality, that absolutely limits the choices of both adults and children. [Then] there is a global food industry where a company like Nestlé admitted earlier this year that more than 60% of its products are unhealthy — so what does that mean, in terms of the food choices that are available and are affordable?”

Witten says if South Africa is to successfully turn our malnutrition crises around, we should follow the examples of Brazil, Mexico and other countries that have created a demand for government to support healthy eating comprehensively.

“In South Africa,” Witten says, “nobody is objecting to the fact that retail stores can package R300 of starchy, high-fat foods, and Child Support Grant recipients [13 million children in South Africa are on it] buy that, and that’s their saving grace.”

Legislation alone will not solve the problem

According to University of the Western Cape researcher Tamryn Frank, southern Africa saw ‘the world’s highest proportional increase in child and adolescent obesity’ between 1975 and 2016 — an alarming 400% per decade. (Photo: endocrinologyadvisor.com / Wikipedia)

Frank defends the need for legislation to curb the South African and global obesity pandemic that “has become pronounced with the proliferation of the ultra-processed food and beverage industry”. But she is also realistic about the scale and the complexity of the problem.

“Unfortunately, the food system is broken. There are no quick fixes or magic bullets… there is no one, single effort that will resolve everything.”

Having front-of-package (FOP) warning labels is “a first step”, Frank says, as a mechanism to identify the unhealthy products that should not be marketed to children.

“One wants to ensure that the UPF companies stop doing what they’re doing — in the ideal world, I’d love to see a completely changed food environment where healthy foods are available and affordable and also desirable.

“At the moment, that seems like very wishful thinking because there’s so much that needs to change,” she says, like addressing the problem of the powerful UPF industry, how to create widespread understanding of what healthy eating looks like, and how to solve the deal-breaking issue of how to enable most South Africans to afford healthy food.

“Just putting regulations in place to stop what the ultra-processed food industry is currently doing is not enough — we need to be able to realise the right to sufficient food, which means that people have access to healthy, nutritious food that is culturally appropriate,” Frank acknowledges.

Witten puts this more starkly: “People do not make decisions because of health information or nutrition information. They don’t know what the nutrition [label] stands for; they don’t know what that information means… they buy what they can afford.”

Also, FOP warning labels are by definition labels on packaged — not fresh — foods. “If those are 80% of the foods that poor people eat, and front-of-pack labelling says ‘this is not what I’m supposed to eat but it’s the only thing I can afford’, that makes me feel bad. Why do we want to make people feel bad?”

Frank acknowledges that the warning label approach is not a complete solution to the “rock and a hard place” conundrum Lake describes.

“Without receiving massive amounts of education, people generally know that fruits and vegetables are nutritious,” Frank says, “and know that chips and sugary beverages are not the best things to be having. It’s the socioeconomic conditions of our country that are informing what people are eating.”

South Africa’s next steps

There are at least three reasons to be hopeful.

Two pieces of legislation are in the works aiming to better control marketing to children of any form of harmful content (not just unhealthy food), as well as a government initiative to create a fully representative council that will advise government on how to transform our nation’s eating habits.

First, there is the legislation that will replace the 2014 amendment-that-wasn’t, R429, which is expected to introduce an easily, quickly understandable warning label for all packaged foods, as well as restrictions on advertising and marketing targeting children.

Second, there is the Audio and Audio-Visual Content Services (AAVCS) Policy Framework, which was most recently in the public domain as a White Paper from the Department of Communications and Digital Technology, but has not yet made its way into legislation on the marketing-to-children issue. (Maverick Citizen requested comment from the department but there was no response by the time of publishing.)

The policy framework has, as a guiding principle, the aim to protect children from harmful content that may impact their physical, mental or moral development, and to extend the existing protections (e.g. for tobacco and alcohol) for consumers into digital platforms, including social media, which are currently unregulated (see sidebar below: Social media policies on junk food advertising).

Researchers and advocates are hoping that those protections will also be broadened to include foods that are high in unhealthy fats, salt and free sugars.

Lori Lake presented to the DCDT in May 2021 in order “to make clear the links between the consumption of unhealthy foods in childhood and how that really sets children on the trajectory to overweight, NCDs, and obesity in adulthood — and in trying to arrest that epidemic we need to start really early in childhood”.

One source told Maverick Citizen that “the AAVCS is being transformed into bills bit by bit”. Asked whether the Directorate, Food Control (within the NDOH) was coordinating its food-related policy work with the DCDT, the source (who is not within the NDOH) said, “there is no formal indication that the Department [DCDT] has engaged with Food Control.”

Third, there is the soon-to-be-formed National Food and Nutrition Security Council, under the Department of Planning, Monitoring and Evaluation, which has as one of their strategic objectives how to improve the food and nutritional status of South Africans.

It is hoped that the council will finally get to grips with — and enable solutions for — the reality that Lori Lake described of poverty (and lack of awareness) driving unhealthy food choices. (Proposals for members to serve on the council will be called for by around March 2022, Witten says.)

More than a quarter (27%) of South Africa’s children are stunted due to malnutrition, hunger and micronutrient deficiencies, resulting in stunted physical growth, diseases in childhood (such as kwashiorkor) and metabolic diseases in later life, as well as permanent damage to a child’s mental development. (Photo: healthtimes.co.zw / Wikipedia)

The council will be “very much focused on a pro-poor, pro-access ideology”, Witten says, “which is what we need to work with if we are going to change things for all South Africans.”

Witten suggests that “we work from the principle that we want to have a healthy, unrefined, whole-food diet, which is what Brazil focused on. Brazil did not focus on front-of-pack labelling — yet Brazil is 20 years ahead of us. How did they do that?

“Because they promoted from the garden. They went from the farm and said, ‘if it is grown and you can eat it directly from the farm, that’s what we should be doing’. Why aren’t we doing that in SA? Because we still want to support the food industry.”

Clearly, there is a need for what policy wonks call “joined-up” food policy — a coordinated, integrated, holistic view of all the dimensions of what goes into and comes out of the food system, and how to make it easy for consumers to make choices that are fully supported by government policies and guidelines, including those governing the private sector.

“I would say to government,” Witten offers, “that for all our children, and predominantly black children on the Child Support Grant (CSG), can we have a subsidised food basket for them?

“Even if we are only subsidising eggs, milk, fresh fruits and vegetables, meat, fish. Why can’t we have that? Why can’t we be asking our retailers — who were so great during Covid in giving food parcels — why can’t we ask them to subsidise anybody who has a CSG?

“We must push ourselves as a country to demand solutions.”

NOTES:

- The new National Food and Nutrition Security Council (FNSC) is a new body (proposed in the National Policy on Food and Nutrition Security of 2014) under the leadership of the Department of Planning, Monitoring and Evaluation. The 2013 policy calls for “a National Food and Nutrition Advisory Committee, comprised of recognised experts from organized agriculture, food security and consumer bodies, as well as climate change and environmental practitioners and representatives of organised communities”. Calls for nominations for members to serve on the FNSC are expected to be opened before the new financial year (March 2022).

- A ‘periodic’ report owed by South Africa to the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC), which South Africa has ratified, was due in 2021; according to the Office of the Rights of the Child in the Department of Social Development, this will be submitted in February or March 2022

Countries that restricted marketing to children

A number of countries have enacted legislation to restrict food marketing to children and to introduce front-of-pack (FOP) labelling and logo or ratings systems to help consumers understand the nutrient content, health benefits or potential harms of packaged foods.

Advertising restrictions were imposed in:

Early 1980s: Quebec, Canada, prohibits companies advertising to children under 13.

1992: Norway prohibits marketing directed at children under 13. Currently a self-regulatory scheme covers all forms of marketing specifically aimed at children under 13, including social media (eg, chat services, blogging tools and internet communities), games and play sites.

2004: Iran prohibits the advertising of soft drinks (sugar-sweetened beverages).

2012: Spain updates its co-regulatory code to cover marketing on the internet directed at children under 15 (however, no nutritional criteria are applied).

2012: Chile outlaws advertising of food in schools, enacts laws restricting advertising directed at children under 14 of foods high in fat, sugar and salt (HFSS foods).

2014: Mexico imposes restrictions on advertising food and sweetened beverages on TV (2.30am to 7.30pm on weekdays, 7am to 7.30pm on weekends).

2017: Ireland’s Department of Health issues a voluntary code of practice to limit the promotion, marketing and sponsorship of HFSS foods and to encourage healthy eating.

2017: The UK bans the inclusion of HFSS product advertisements in children’s media and other media where children make up 25% or more of the audience.

2021: The UK passes into law one of the toughest marketing-restriction regulations in the world, banning all paid-for forms of digital marketing, from ads on Facebook to paid-search results on Google, text message promotions, and paid activity on sites such as Instagram and Twitter. It will come into effect in October 2022.

Sources: Tomlinson AAVCS presentation; WHO Digital Marketing report; The Guardian newspaper.

WHO’s CLICK monitoring framework

The World Health Organization’s Europe office has conducted extensive research into advertising to children via digital media. It has found that within its European Union member states:

“The response from governments and public health institutions to this threat to children’s well-being is lagging far behind, and efforts are complicated by rapid changes in digital and programmatic marketing strategies. Tools and support are urgently needed to facilitate monitoring and implementation of the WHO recommendations in online settings.”

In March 2019, WHO Europe published Monitoring and Restricting Digital Marketing of Unhealthy Products to Children and Adolescents, an 85-page document that proposes “two practical actions that can be feasibly undertaken”:

- “A monitoring tool called the ‘CLICK monitoring framework’ (see below): a five-step process designed to gather data on children’s exposure to marketing, providing Member States of the WHO European Region with the evidence they urgently need to call for and catalyse national action.

- “Proposed policy prerequisites: three suggested policy actions on age verification and tagging of advertisements that could lead to a significant reduction in children’s exposure to advertising of unhealthy products”.

CLICK Monitoring framework

C – comprehend the digital ecosystem

L – landscape of campaigns

I – investigate exposure

C – capture on screen

K – knowledge sharing

Note: The approach summarised in this report was devised during a multidisciplinary expert meeting held on 5-6 June 2018 by the WHO Regional Office for Europe. The material in this sidebar is adapted from WHO’s ‘Monitoring and Restricting Digital Marketing of Unhealthy Products to Children and Adolescents’ 2019 report.

Examples of countries’ introduction of front-of-pack (FOP) labelling regulations

1989: Sweden establishes criteria for, and introduces the Keyhole logo (detailing saturated fat, total sugar, sodium).

1993: Finland implements mandatory display of warning labels on foods high in salt.

1998: Singapore implements the Healthier Choice symbol. (In 2015 it launches a “refreshed” symbol based on revised nutrient guidelines).

2006: The Netherlands is the first country to introduce the Choices Programme logo.

2007: Thailand makes “Guidelines Daily Amount” and warning labels mandatory for five categories of snack foods, and introduces a voluntary logo for products with 25% less salt, sugar, or saturated fat.

2008: Poland introduces Choices Programme.

2009: Sweden, Denmark and Norway launch a common voluntary Keyhole logo to identify healthy foods.

2009: Fiji/Solomon Islands introduce on-shelf labels for foods high in fat.

2011: European Union allows member states to develop voluntary FOP guidelines which allow Guideline Daily Amount or voluntary “traffic light” styles.

2012: Chile approves a law on food advertising and labelling to require warning labels for products high in salt, sugar, fat and energy (calories); mandatory warning labels come into effect in 2016.

2013: Ecuador introduces mandatory “traffic light” labelling for sugar, fat and sodium.

2014: Australia/New Zealand introduce the voluntary Health Star Ratings system.

2015: Mexico requires Guideline Daily Amounts to be displayed on the front of all food packages; Sweden, Denmark, Norway, Iceland and Lithuania introduce stricter requirements for Keyhole logo.

2016: Israel proposes warning labels for sodium, total sugar and saturated fat.

2017: France implements the voluntary Nutri-Score labelling system.

2018-2019: Chile implements second and final phases of more restrictive nutrient limits for mandatory warning labels.

Source: Adapted from World Cancer Research Fund International (2017) NOURISHING framework: Nutrition label standards and regulations on the use of claims and implied claims on food. (Accessed November 2017).

Social media policies on junk food advertising

Adapted from “Social media platforms need to do more to stop junk food marketers targeting children” – Gary Sacks and Evelyn Suk Yi Looi, Deakin University, in The Conversation, 29 November 2021.

A quick summary

- The authors’ study focused on the 16 largest social media platforms globally. These included platforms popular with children, such as Instagram, TikTok, YouTube, Snapchat and Facebook.

- They examined each platform’s advertising policies related to food and drinks.

- They found that none of the social media platforms have comprehensive restrictions on the advertising of unhealthy foods to children.

- YouTube Kids, a platform popular with children under 13, does ban direct junk food marketing. But media reports have shown children could still be exposed to junk food brands through product placement and promotional videos on the platform.

A call for common, global regulations on social media

- Public health groups have consistently highlighted that food industry self-regulation in the area of junk food marketing has proven ineffective. As such, there are strong global recommendations for comprehensive national and international government regulation.

- But the potential role of social media platforms in regulating junk food marketing has largely escaped attention.

- While we await further government regulation, social media platforms can take immediate action to protect children from the marketing tactics of junk food advertisers. This would be a critical contribution to efforts to improve young people’s diets and address the growing problem of obesity worldwide. DM/MC

You can read Part One here and Part Two here.

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

This is territory that most parents don’t want to go into. Both a chocolate cake and super refined mealiemeal fall very definitely into the definition of ultra-processed foods.

As adults we don’t like whole-grains so how are we going to convince parents to go back to eating mealies and wholewheat bread?

The first step is to stop being politically correct. Telling the obese straight that they are going to have serious pain and disability from non communicable diseases is not fat-bashing. It’s speaking the truth.

I can’t see us compelling newspapers, magazines and television stations to several times daily having clips of the obese in wheelchairs, using walkers and shooting themselves with insulin. But that’s what it will take to give South Africans a wake-up call. It has to be shouted from the rooftops, but we won’t. It’s not PC. They must just suffer, and their children too.