TURKANA MAN

Richard Leakey — a giant among students of human origins

Famed paleoanthropologist and ecological and environmental warrior Richard Leakey died on the second day of 2022. His legacy lives on in the people he inspired and the environmental campaigns he helped ignite.

‘In each great region of the world the living mammals are closely related to the extinct species of the same region. It is, therefore, probable that Africa was formerly inhabited by extinct apes closely allied to the gorilla and chimpanzee; and as these two species are now man’s nearest allies, it is somewhat more probable that our early progenitors lived on the African continent than elsewhere.”

— Charles Darwin, The Descent of Man

Despite Charles Darwin’s inspired hunch in the middle of the 19th century about the origins of humanity, the prevailing wisdom among Victorian naturalists was that human origins were inevitably European, or at a minimum, Eurasian.

The astonishing discoveries of Neanderthal skeletons back in the mid-19th century, and then, later, discoveries of bones and skulls of Peking Man and Solo Man in China and the Dutch East Indies respectively, kept a focus on a presumed Eurasian origin of humanity — even if such discoveries were not of actual early humans, but more realistically the ancient precursors to our own ancestors.

In recent years, recognisably modern human remains have been dated to around a quarter of a million years old, per Darwin, in Africa, before the great migration out of that continent.

Back at the beginning of the 20th century, for a time, with the apparent ascendency of western Europe plainly visible in virtually every conceivable sphere of human endeavour, the search for human origins narrowed its focus further to the British Isles. The discovery of the infamous “Piltdown Man” skull in a gravel pit in southern England — what with its perfect combination of apelike and human features, was cheered as a stunning example of the fabled “missing link”.

This discovery was even seized upon as proof of the likely British origins of humanity. Even the exposure of Piltdown Man as a very carefully constructed fake that artfully merged human and ape features did not shake the sense that non-counterfeit, early humans were still to be found in Britain or Western Europe, especially as recognisably modern human “Cro-Magnon Man” remains began to emerge in European excavations, along with those brilliant, and largely contemporaneous cave paintings in France and Spain.

Paleoanthropologists and fossil hunters were still paying obeisance to the idea of a Eurasian origin of humanity, or sometimes, in the multiple sources of evolution of humankind from earlier creatures that would, in turn, have evolved into the distinct races. Such a view can be heard from some laypersons. An eminent paleoanthropologist like Carleton Coon could still articulate that view into the 1950s.

By contrast, Roy Chapman Andrews (the reported real-life model for cinematic character Indiana Jones) carried out several explorations — complete with dramatic encounters with Chinese armed bands, dust storms and yet other travails — into the Gobi Desert to hunt for the fossils that would prove a Central Asian origin point for all humanity. He never found any, of course, but he did uncover vast troves of dinosaur fossils, including dinosaur eggs preserved in their nests in the Flaming Cliffs of Mongolia. His books about those adventures captured the imaginations of generations of youngsters (including this writer).

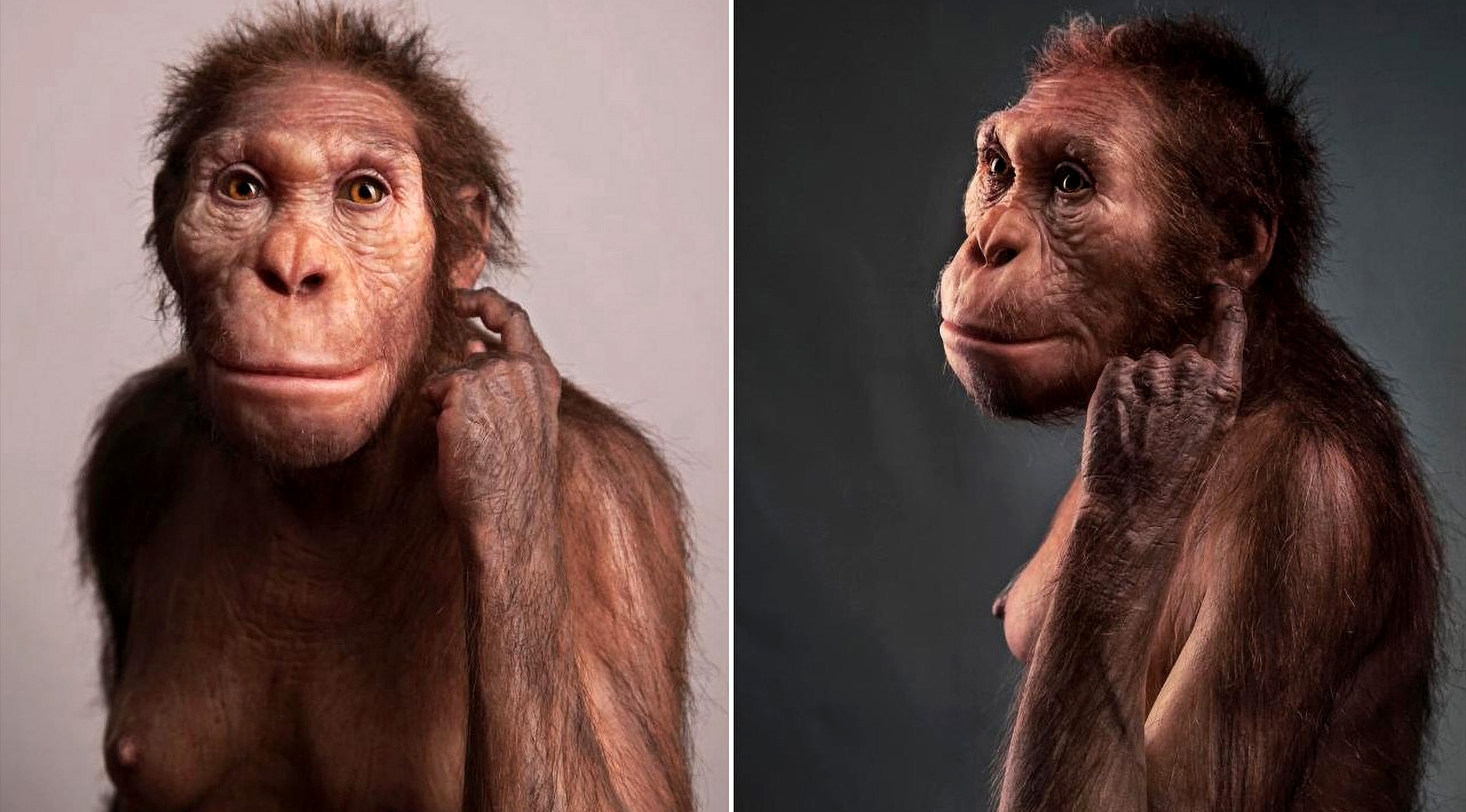

Life reconstruction of Australopithecus sediba, commissioned by the University of Michigan Museum of Natural History. (Sculpture: Elisabeth Daynes / Photo: S Entressangle)

Even though the discoveries and descriptions of the Taung Child in South Africa, and parts of several other tantalising fossils, had led to cracks in the edifice of the idea that the origins of early humankind were Eurasian, most leaders in the field remained unconvinced about any such alternative view, despite Darwin. Eventually, it took Louis and Mary Leakey, bucking the mainstream with discoveries well beyond the common view, to pull the paleoanthropological community towards revisiting Darwin’s surmise. Over many years, the Leakeys’ excavations in the Olduvai Gorge, along with still other exciting discoveries in Tanzania and in Ethiopia, brought about a revolution in thinking about human origins, through the remarkable discoveries of a growing catalogue of Homo Habilis and Australopithecus fossil skulls — and, crucially, early stone tools.

Increasingly, in response to the Leakeys’ discoveries, along with a growing roster of other paleoanthropologists working across Africa, new discoveries are revealing that human origins are much less a rather linear evolutionary ladder toward modern humankind, and much more like the luxuriant, complex, interwoven branches of an ancient bush. There was a range of ancestral hominin forms across Africa, and competing branches that eventually died out beyond Africa, but not before such branches contributed some of their DNA — via the usual method — to give rise, ultimately, to the human species we are today.

Kenyan palaeoanthropologist Richard Leakey speaks at a press conference in London, to talk about his discoveries regarding human evolution, 9th November 1972. The skulls are those of a Paranthropus boisei discovered in 1969 (right) and a Homo rudolfensis discovered in 1972 (left). (Photo by Keystone/Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

As an example of his revolutionary thinking, Louis Leakey was also responsible for sending Jane Goodall, Dian Fossey and Biruté Galdikas to follow chimpanzees, gorillas and orangutans — the three primate species closest to humans — in their own natural environments, to study their behaviours and societies for possible clues and insights into those of early humans and our still earlier forebears.

Goodall’s reports of the way chimpanzees fashioned tools out of available materials (and passed this knowledge on to others) to fish those nutrient-rich termites from inside tree stumps, took what had been seen as a defining trait of humans — tool creation — and thoroughly challenged that idea. Louis Leakey responded to the critics of Goodall’s observations by saying, “Now we must redefine tool, redefine Man, or accept chimpanzees as humans.”

Over time, the Leakeys passed the baton on to their son, Richard, who was born in Kenya. Throughout his own extraordinarily eventful life, Richard Leakey not only made important contributions to paleoanthropology, but also to Kenya’s public life, as well as a growing global consciousness about environmental protection and ecology. And along the way, Richard Leakey made deep impacts on some of South Africa’s leading paleoanthropologists as well.

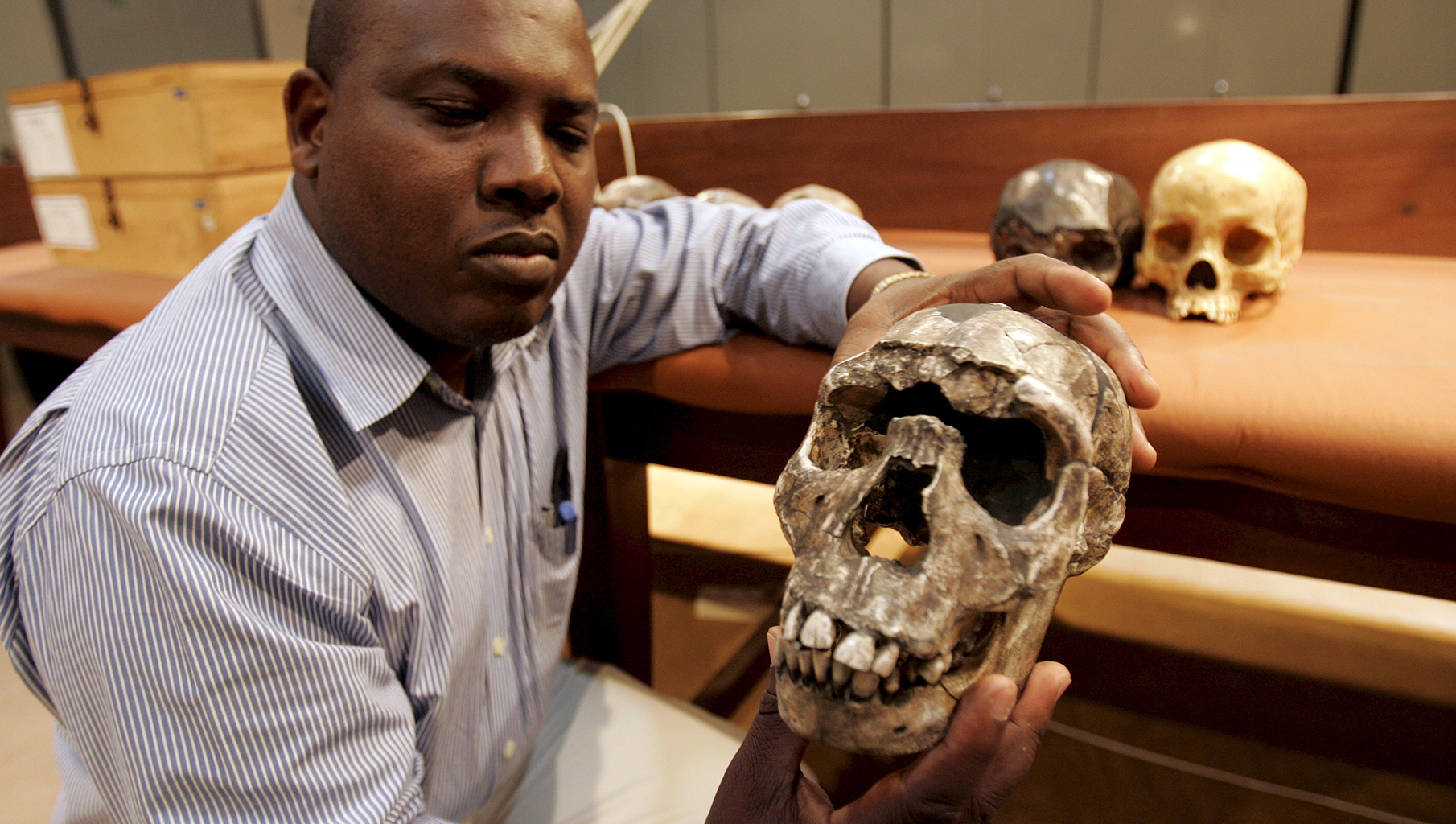

Dr Frederick Kyalo Manthi holds a plaster cast of the Turkana Boy skull at the National Museum of Kenya in Nairobi, Kenya. (Photo: EPA / Stephen Morrison)

In 1984, Richard Leakey continued with the family tradition of near-preternatural success in finding important fossils — sometimes enviously called “Leakeys’ luck” by competitors — when he located the 1.5-million-year-old remains of a hominin, named “Turkana Boy”. By the time the excavation was completed, nearly 40% of the specimen’s bones had been uncovered. This is in comparison to most discoveries that usually just include parts of a skull and a few other bones. In fact, this so-called Leakey’s luck was really a recognition of the family’s remarkable skill in identifying fossil remains from the confusing welter of stones and rocks in situ, on the basis of subtle clues observed by a well-trained, very observant individual.

Richard Leakey continued his efforts in paleoanthropology, public service and environmental protection well into his 70s, despite having suffered numerous medical issues, beginning with a fractured skull as a teenager that was followed by skin cancer, kidney and liver diseases, two kidney transplants, and, perhaps most notably, having had both legs amputated as a result of medical complications after he had survived a near-fatal plane crash.

Almost as remarkable as his medical history and his tenacity is that, while Richard Leakey was not even a formally academically trained researcher, he had won a research grant to explore the shores of Kenya’s Lake Turkana. In the 1970s, those expeditions revealed new insights about human evolution, especially from the 1972 discovery of a Homo habilis skull (1.9 million years old), and then, three years later, Homo erectus bones (1.6 million years old). These discoveries famously put him on the cover of Time magazine, posing with a model of the first skull, and the headline and story: “How Man Became Man”.

The BBC, reporting on his death, explained that while still in his 20s, “Leakey made his own important finds, and in two groundbreaking books (Origins and People of the Lake), he explained the emergence of Homo erectus, an ancestor of modern humans.”

Building upon such discoveries, he became the featured scientist in the BBC’s 1981, seven-part television series, The Making of Mankind. A few years later, there was another astonishing discovery, that near-complete Homo erectus skeleton, nicknamed, “Turkana Boy”. The Turkana explorations have, so far, resulted in uncovering more than 200 fossil remains.

9th November 1972: Kenyan palaeoanthropologist Richard Leakey examines jawbone fossils in the laboratory of the National Museum in Nairobi. (Photo by Keystone Features/Getty Images)

During the 1980s Leakey also became one of the world’s preeminent voices against what was a still-legal ivory trade. By the end of the decade, Kenyan president Daniel Arap Moi had made Leakey head of the Kenya Wildlife Service (KWS). Despite a generally self-effacing manner, some of Leakey’s campaign methods were devised to garner global attention.

As the Guardian, noted, “He masterminded a spectacular publicity stunt of burning a pyre of ivory by setting fire to 12 tonnes of tusks — making the point that once removed from elephants they had no value. He also held his nerve when implementing a shoot-to-kill order against armed poachers.” About that order, he once told the Financial Times that he endured “regular threats” and lived with armed guards, adding: “But I made the decision not to be a dramatist and say: ‘They tried to kill me.’ I chose to get on with life.”

Eventually, he was pushed out of that government position and began a new effort as an opposition political figure, criticising the rampant corruption of the Moi regime. Defeated at the polls, in an unusual turnabout, the Kenyan leader appointed him to head the civil service to fight corruption, although he gave up that fight after a two-year period.

Several years later, as elephant poaching was once again on the rise throughout Africa, another Kenyan president, Uhuru Kenyatta, called him back to government as chairman of the board of the Kenya Wildlife Service, a position he would keep for three years. His last project before his death was a large museum in Kenya to celebrate human evolution and to draw attention to the effects of climate change.

Smithsonian magazine commented, “Before his passing, Leakey dreamed of opening a museum honoring humankind, named Ngaren, to translate the science of human origin into captivating content. When construction begins in 2022, the museum is set to open in 2026 and will overlook the Rift Valley, where Turkana Boy was discovered. ‘Ngaren will not be just another museum, but a call to action. As we peer back through the fossil record, through layer upon layer of long-extinct species, many of which thrived far longer than the human species is ever likely to do, we are reminded of our mortality as a species,’ Leakey said in a statement [at the announcement of its launch].”

When I asked paleoanthropologist Lee Berger about Richard Leakey, he reminisced about Leakey having been largely responsible for Berger coming to South Africa more than 30 years ago and then staying on to become a leading figure at the University of the Witwatersrand. Berger had met Leakey in the US while Berger was still trying to determine what he should do and where he should go for his PhD research. In their meeting, Berger said, Leakey had encouraged him to think beyond East Africa, then the hotspot for research on hominins, and, instead, pick up where work following on those earlier South African discoveries had largely gone quiet.

Despite the deeply uncertain political circumstances in South Africa in the late 1980s, Berger embraced Leakey’s advice and now says he has really never looked back. In recent years, he and his team’s spectacular finds of the Sediba and Naledi hominids in those Cradle of Humankind caves have helped turn South Africa into one of the prime places for new discoveries in human evolution.

Meanwhile, Christine Steininger, another American whose career in paleoanthropology has taken off in South Africa, wrote to say, “While I was attending the 50th Anniversary of Zinjanthropus (now Paranthropus) Workshop at the Turkana Basin, hosted by the Turkana Basin Institute and Stony Brook University, Richard made all the participants scrambled eggs. They were the best scrambled eggs I ever had. He even taught me how to make them, but I still cannot replicate them. He was an amazing storyteller and had us in stitches during the early evenings after our intense discussions on Paranthropus morphology, dietary behaviours and ecology.”

From the secrets of those gourmet scrambled eggs prepared in the field kitchen of a research station by the shores of Lake Turkana, to astonishing discoveries about humanity’s origins, to communicating the thrill of those discoveries to millions via television, and to protecting Africa’s endangered wildlife and the continent’s threatened environment, Richard Leakey’s career was an extraordinary one. And his career, through all its manifestations, helped explain and clarify our connectedness to our remote past, as well as demonstrate the fragility of our global surroundings — and the need to preserve what we still have. DM

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

Thanks for that Brooks. Richard Leakey was certainly a fascinating person and, as I understand it, not always well liked.