EDUCATION OP-ED

The 30% matric pass mark: To increase or to scrap, and why all the excitable commentary?

If we scrap the 30% pass mark, our expectation of each Grade 12 learner is: Choose your NSC subjects wisely and get the best marks that you can in all your subjects. The higher your marks, the more opportunities for further study and work will open up for you. You can’t fail as there is no ‘pass mark’. Whatever marks you get, those marks are printed on your NSC certificate.

It’s January 2022. In South Africa we await “the matric” or National Senior Certificate (NSC) results. They are a little later than before, as our 2021 school started later than usual.

Yet again we have some South Africans frothing at the mouth and exasperated about the “30% pass” mark. This year the 30% pass exasperation pack is led by Mmusi Maimane. His current pinned tweet:

“I am calling for the end to the announcement of matric results based on the 30% standard. The impact of the 30% based results announcements is this:

- We inflate matric success metrics.

- We mask the real state of our education system.

- We entrench low expectations and stereotypes.” (tweet, @MmusiMaimane, 28 Dec 2021).

Ja, né? Politics is politics. Politicians will be politicians.

Maimane’s provocation is an attack on the leadership of Basic Education Minister Angie Motshekga. This is clear in his tweets such as: “Reason 1001 why we need a new minister of basic education. #AngieMustRest #End30PercentMatric” (9 January 2022) and “The Minister of Education should resign” (9 January 2022).

On 8 January Maimane tweeted: “We must END 30% MATRIC PASS MARK.

- It sets low expectations across the board.

- It obfuscates the state of our education system and inflates the past (sic) rate.

- It allows poor education leaders like #AngieMotshekga to dodge accountability.

END IT.”

Ja, né? Politics is politics. Funny how, on the day the ANC has its 110th birthday celebration and its January 8 address, we see the far younger, and much smaller, political parties (or “movements”) desperate to claim some media time. Mission accomplished: Maimane has been on TV.

But setting politicking aside, the “30% pass mark” debate remains stubbornly fake news in South Africa. In this article I argued that the 30% pass exasperation is clung to by those who:

- Think that you pass matric with 30%;

- Think that the government is just making schooling, and so matric, easier and easier;

- Just can’t internalise that a learner who doesn’t know 70% of a subject matter is deemed to have passed that subject; and

- Think that expectations matter.

I argued that, instead of being exasperated by a 30% pass and lobbying to increase it, we rather scrap it altogether. How would this work?

Simple, really.

Matric results have two purposes. The first is as a currency for the individual matriculant to access higher education or the world of work. The second is to monitor the quality of our schooling system over time.

How would scrapping the 30% pass mark work for an individual learner?

Every young adult who writes matric is issued with a matric certificate (called an NSC or National Senior Certificate). Their marks for each subject (as a percentage) are recorded on their NSC. They use their NSC certificate to seek work or apply for further study.

If we scrap the 30% pass mark, our expectation of each Grade 12 learner is: choose your NSC subjects wisely and get the best marks that you can in all your subjects. The higher your marks, the more opportunities for further study and work will open up for you. You can’t fail as there is no “pass mark”. Whatever marks you get, those marks are printed on your NSC certificate.

How would scrapping the 30% pass mark work for monitoring the quality of the schooling system?

To measure quality, we have to measure attainment (marks across the chosen subjects) over time.

How do we currently monitor the quality of our schooling system, using matric results? We make comparisons and use the same ruler to measure this each year. So we set thresholds to define different levels of attainment. We make home language, first additional language, life orientation and mathematics/mathematics literacy/technical mathematics compulsory.

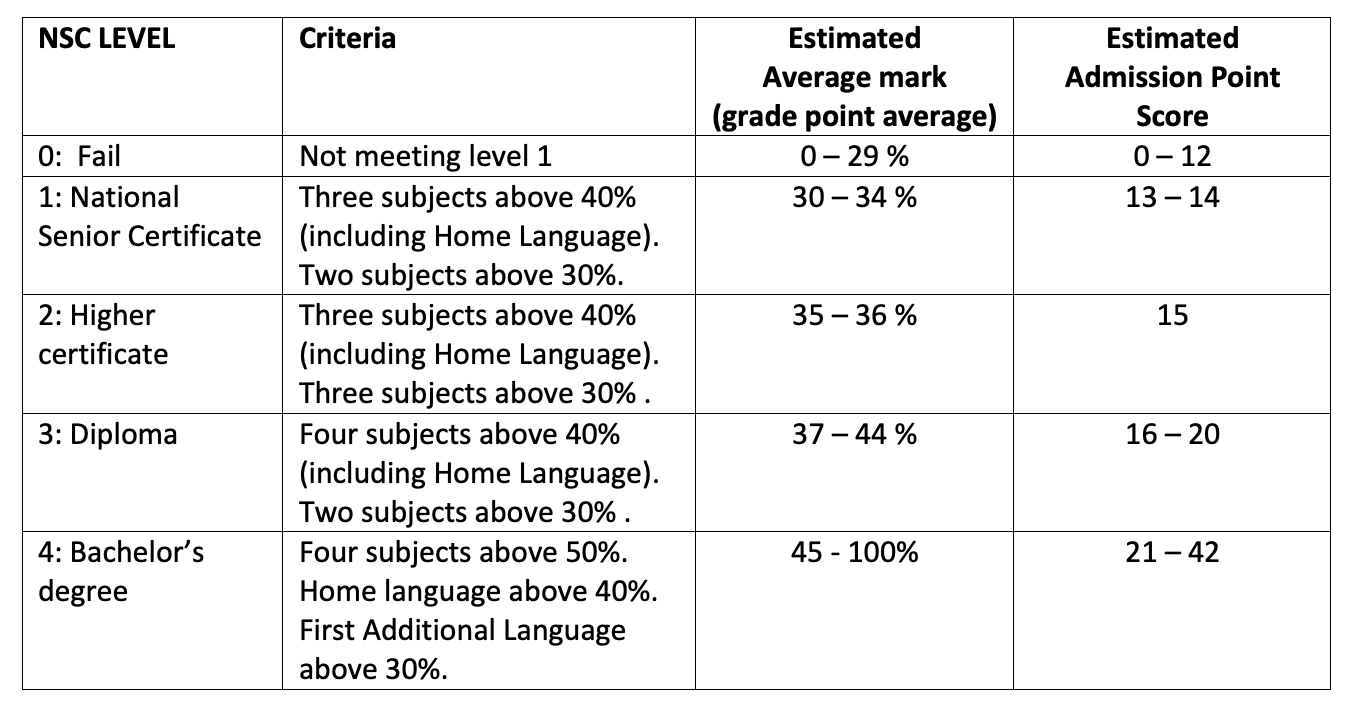

We basically take the results from all the learners who wrote six subjects for matric (excluding life orientation). We then put each learner into a particular basket with each basket representing a different quality of NSC results. We currently define the boundaries between the baskets using the following criteria:

- LEVEL 0: Fail. All those who did not obtain level 1.

- LEVEL 1: National Senior Certificate level. Three subjects above 40% (including home language). Two subjects above 30%.

- LEVEL 2: Higher Certificate level. Three subjects above 40% (including home language). Three subjects above 30% .

- LEVEL 3: Diploma level. Four subjects above 40% (including home language). Two subjects above 30% .

- LEVEL 4: Bachelor degree level. Four subjects above 50%. Home language above 40%. First additional language above 30%.

If we scrap the 30% pass mark, we just don’t call LEVEL 0 “a fail”. LEVEL 0 is simply, “Did not obtain LEVEL 1”.

To monitor the quality of our schooling system, we monitor the proportion of learners falling into each basket of attainment. Our expectation is that we see increasing proportions of learners getting higher levels of attainment (better results) over time. We report on this annually, and reflect on this in five-year cycles. We reflect on the results as well as the subjects offered and the curricula of those subjects.

To monitor the quality of our education system, we should also be interested in how many people study in schools, at FET colleges in learnerships.

What do we expect from the matric results announcement in 2021?

When the minister announces the “matric” results to the nation, she reports on the number and percentage of learners who obtained their matric at each NSC LEVEL. This is already being done by Minister Motshekga. The team at the Department of Basic Education detail all of these issues in NSC technical reports, which are provided online the day after the results are released.

See here for reports on NSC results from 2009 to 2020.

The 30% matric exasperation is an inappropriate focus on how we define our baskets of quality performance. It focuses on the threshold that just defines who goes into the first basket. But the baskets are essentially arbitrary.

We have to have some baskets that catch learners who are doing badly – and so have fewer opportunities open to them for further study or employment. We must also have some baskets that catch learners who are doing well – and so take their pick of future opportunities.

Importantly, we need to use the same ruler for how we place people into these baskets, so we can make comparisons over time.

The 30% matric pass exasperation focuses on the ruler that we use to measure quality over time. But it is important to realise that which baskets we use remains arbitrary. However we define our ruler, its purpose is to allow us to track changes over time.

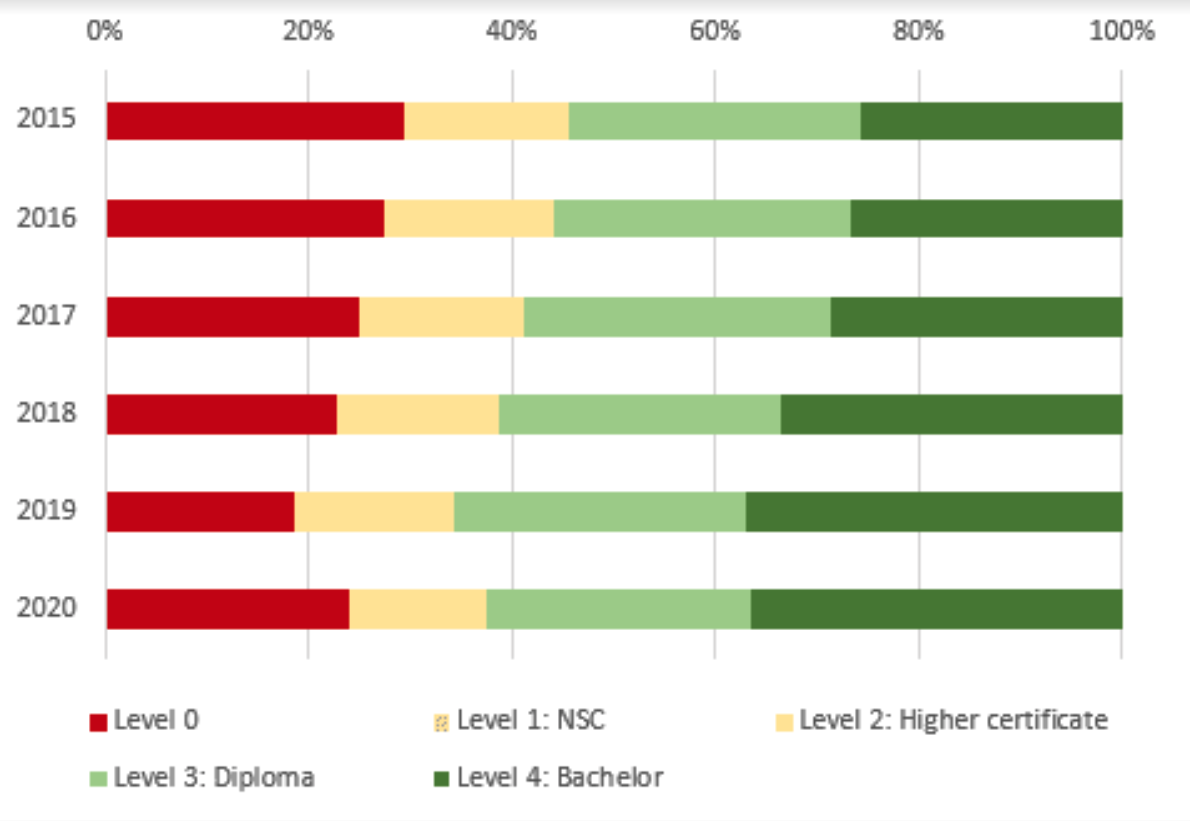

This how the proportions of matriculants performing at each attainment level has changed over time in the last six years:

NSC results by level from 2015-2020

Notice:

- LEVEL 2: NSC is basically redundant. At most, 0.02% learners fall into this basket.

- The increase in proportions of highest-quality (LEVEL 4: Bachelor’s) passes from 2015 to 2019.

- The effect of Covid-19 pandemic: There is an increase in Level 0 in 2020. However, the proportion of Level 4 passes only slightly declined.

If we did not use the current 5 NSC LEVELS to define attainment baskets, what ruler could we use to measure our educational quality?

Lobbying for an increase in the 30% pass/fail threshold simply tinkers with our ruler. It draws unnecessary attention to the boundary between LEVEL 0 and LEVEL 1. We could make more fundamental changes to how we monitor the quality of matric outcomes.

There are several other ways to think about the distribution of the matric results, and so monitor quality over time.

One way we could change our ruler is to use Grade point averages (the learner’s average mark) to define thresholds for each basket. Calculating the average mark is a way of changing the six subjects, each with their own percentage, into a single average mark for each NSC learner.

We can illustrate this using the information provided to define the current LEVEL 0-4 baskets. Let’s take LEVEL 4: Bachelors pass. The criteria for LEVEL 4 are: Four subjects above 50%, home language above 40% and first additional language above 30%. The minimum total marks for a learner at passing LEVEL 4 is: 50 + 50 + 50 + 50 + 40 + 30 = 270. Their NSC average is therefore a minimum of 45%.

What do we lose by just using an average mark (or Grade point average) instead of the criteria?

- We do not require a minimum threshold for home language.

- We do not allow for a lower mark in first additional language.

- We do not require achievement of over 40% or 50% in a minimum number of subjects.

Another way we could change our ruler is to use the Admissions Points Score (APS) currently used by most South African universities, and apply this to all NSC learners. The APS is another way of changing the six subjects, each with their own percentage, into a single score for each learner.

For National Senior Certificate results, the Admissions Point Score for each subject is calculated as follows for each subject:

To get a single number to summarise the learner’s NSC result, you add together the APS points for each subject of the best six subjects (excluding life orientation). This total is the APS for the learner.

A learner who gets six distinctions (As, or all results over 80%) has an APS of 6 × 7 = 42. In contrast, a learner who only just meets the threshold for a LEVEL 4: Bachelor pass, has an APS score of 21. They just meet the Bachelors pass threshold: four subjects above 50% or more, home language above 40% and first additional language above 30%. So, their APS is (4 × 4) + (1 × 3) + (1 × 2) = 21.

The advantage of an APS system is that it allows for comparison between NSC results and other international school systems. Another advantage is that specific universities, or particular faculties in universities, can use the APS system to specify particular admissions criteria. For example:

- You must have mathematics, as mathematics literacy is not accepted; or

- You need a minimum of five points or 60% in your home language.

- Mathematics is more difficult than mathematics literacy so you get an extra 2 points for doing mathematics.

An APS system is already used across most South African universities. So we already have a ruler which measures the quality of our NSC LEVEL 4 Bachelor’s degree passes in more detail. This could be used by the Department of Basic Education to report on the proportions of learners performing in this highest NSC level.

Will changing our ruler improve the quality of teaching and learning in schools?

No. There is a common saying about assessment in education which explains that assessment alone does not improve quality: You don’t fatten the pig by weighing it. Our schooling system will not improve simply by assessing learners.

We must understand the two different purposes of our matric results:

- Matric results are a currency for an individual learner to access further learning or work opportunities. The better a learner does in each subject, the more opportunities open up for them. Matriculants should not be focused on an arbitrary threshold of pass/fail. They should do the very best they can in every subject. I think focusing attention on an arbitrary pass mark threshold of 30%, 40% or 50% distracts them from this goal.

- Matric results are a measure to monitor the quality of our schooling system over time. For this we need to agree on a consistent ruler which allows for comparison from one year to the next. We have used a 5 LEVEL NSC pass system (defined by subject level thresholds and criteria) for at least the last 12 years. To get more detail on proportions of higher-level performance, we could split our Level 4 Bachelors pass basket into smaller categories (using the average mark or the APS).

So in conclusion, where exactly do I stand on the 30% pass mark debate?

Let me answer a few pertinent questions directly:

- Do I think that the 30% pass mark should be increased? No. I think the pass mark should be scrapped altogether.

- Do I think we could have a better ruler to measure the quality of schooling in South Africa? Yes. It seems many people struggle to understand the 5 NSC LEVELS. It would be helpful to have more detail in the NSC LEVEL 4: Bachelors pass.

- Do I think that changing our ruler is our most pressing issue in schooling? Definitely not.

- Do I think that we need to put all our efforts into changing our ruler? No.

- Is the 30% pass exasperation a distraction from what we need to do to keep improving schooling? Absolutely.

I will conclude by rephrasing the common saying about assessment. To be absolutely clear to those who think that changing the 30% pass mark will improve our schooling system: You don’t fatten the pig by changing the scale or adjusting the units used to weigh it.

I hope that understanding the ruler that we use to measure the quality of matric will help South African citizens to better interpret the NSC results.

I look forward to the announcements to be made by Minister Angie Motshegka, and wish the Class of 2021 all the best.

Matric is just one step in a lifelong learning journey. There are many paths open to you. When one door closes, many others remain open. DM

Nicky Roberts is an Associate Professor in mathematics in the Department of Childhood Education at the University of Johannesburg. She has a PhD in mathematics education (Wits), a masters in International perspectives in mathematics education (Cambridge) and a post-doc at the University of Johannesburg. She writes in her personal capacity.

[hearken id=”daily-maverick/8976″]

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

Analysts and political commentators seem to forget that the market (further education and employers) have LONG ago started ignoring the government’s “results”.

Universities have their own entrance exams and requirements.

We would do the bottom 80% (on the APS scores) that should not be planning university a huge favor if we offered job-relevant career paths in school from age 15.

We would also do industry a huge favor as they could need much less resource to have productive employees.

Just in artisans we could address the severe shortage within three years. Forget 4IR. Any growing economy will always need not just technical artisans but anything from construction workers to nursing assistants.

The nonsense about everybody going to fulltime university to not obtain another BA degree in six years must stop. We are setting the youth up for disappointment.

Your interpretation of the graph given in the article is obviously incorrect: The percentage of learners obtaining Level 2 is closer to 15% than 0.02%, and since 2016 there had been a consistent decrease in the proportion of learners obtaining Level 4. There has also been an increase in the percentage of learners in Level 0 over the same time period.

Not obtaining Level 1 = Failure. Semantics cannot hide this fact or fix the problem.

By using an average mark you would actually confirm that matric can be passed with a mark of 30%. With an average mark of 45% one can enroll for a bachelor’s degree. With such low requirements it is no surprise that so many students can simply not make it at university (where the pass rate is 50%) or in the job market.

We should start by having higher qualification standards for political leaders. That would in turn result in them making better decisions about all aspects of citizens lives including education.