Lessons from my father

Don’t leave for tomorrow what you can accomplish today: Lionel Rupert Barrymore Bryce-Pease

My late father would not have been too pleased with my procrastination in getting this project started.

If there was one lesson he taught me early on in life, it was never to leave for tomorrow what you could accomplish today. While I wholly endorse the sentiment, his passing was still quite fresh when I was asked to contribute to a book on “good, meaningful stories about dads”, so I needed time for the idea to percolate – to resonate within – given that writing about him in the past tense is still a fairly new experience in itself.

People say I look like my mom and after hundreds of confirmations in the course of my 42-year life, they’ve convinced me of this striking resemblance. Same nose, freckles, cheekbones. “The eyes; you have your mother’s eyes,” they’d say. Great. Thanks. I didn’t look like my dad because he was, for all intents and purposes, a white man; pink in the summer months, transparent in the winter. I am multiple shades darker. I put it that way because he was – to be clear – of mixed heritage but his appearance was that of a white person, and so, being told that I looked like my dad was never going to pass the stress test.

Certain pupils who attended high school with me in East London were the first to point out my dad’s hue – this was soon after the end of apartheid in South Africa, when formerly segregated schools for the minority white population were opened to all races. I was 13 when I discovered, due to the litany of questions from my peers, that my dad did not have the same skin tone as I did. “Is your dad white?” was a question I confronted regularly from the white boys at my school, a question I had never confronted in all of my 13 years on Earth at the time, and one I promptly put to my father when I got home.

He looked a bit sheepish at the question because he didn’t actually know the answer himself. We later discovered that his grandfather was a British soldier in the Anglo-Boer War and that he had dipped his toe in the African pond, before dying by suicide – or so the story goes. But that’s a chapter for another book.

At around the same time during my high schooling, I would also notice how my parents’ walking together at the mall would elicit stares from passers-by. I eventually asked them why people kept staring at them and to this day I recall Mom’s response: “It’s been happening for years.”

Point is, Dad was just Dad – always – and the inquisition I faced was more a symptom of the times rather than anything to do with how we lived as a family during a fraught time in our country’s history.

I was also closer to my mother growing up, a mommy’s boy as some would say, and I’m okay with that. But in the months since dad’s passing – it’s June 2021 as I write, and we lost him in January – I’ve given our bond a great deal of thought.

***

I’ve often been asked if I had a good relationship with my parents and the answer has always been in the affirmative. Both my parents.

Lionel Rupert Barrymore Bryce-Pease. That was dad’s full name, with all the bells and whistles. Sounds like an English gentleman of noble lineage rather than the tradesman he was by training. When he explained this mouthful to me (around my late teens) it was in the context of how he came to be the only Bryce-Pease in the Pease clan.

“The only Bryce-Pease in the Pease clan?” I asked, questioningly and totally confused.

“Yup”, he continued. “I’m serious.”

He explained that when he applied for his identity document at Home Affairs (or whatever it was called back then) a clerical decision dropped Barrymore because two names were the maximum allowed and Bryce was mistakenly attached to Pease with a hyphen. This made dad, mom and my older brother Laver and I the only Bryce-Peases in the Pease family. News to me, I tell you. But unique, I thought; I loved that we were our own little clan within a clan.

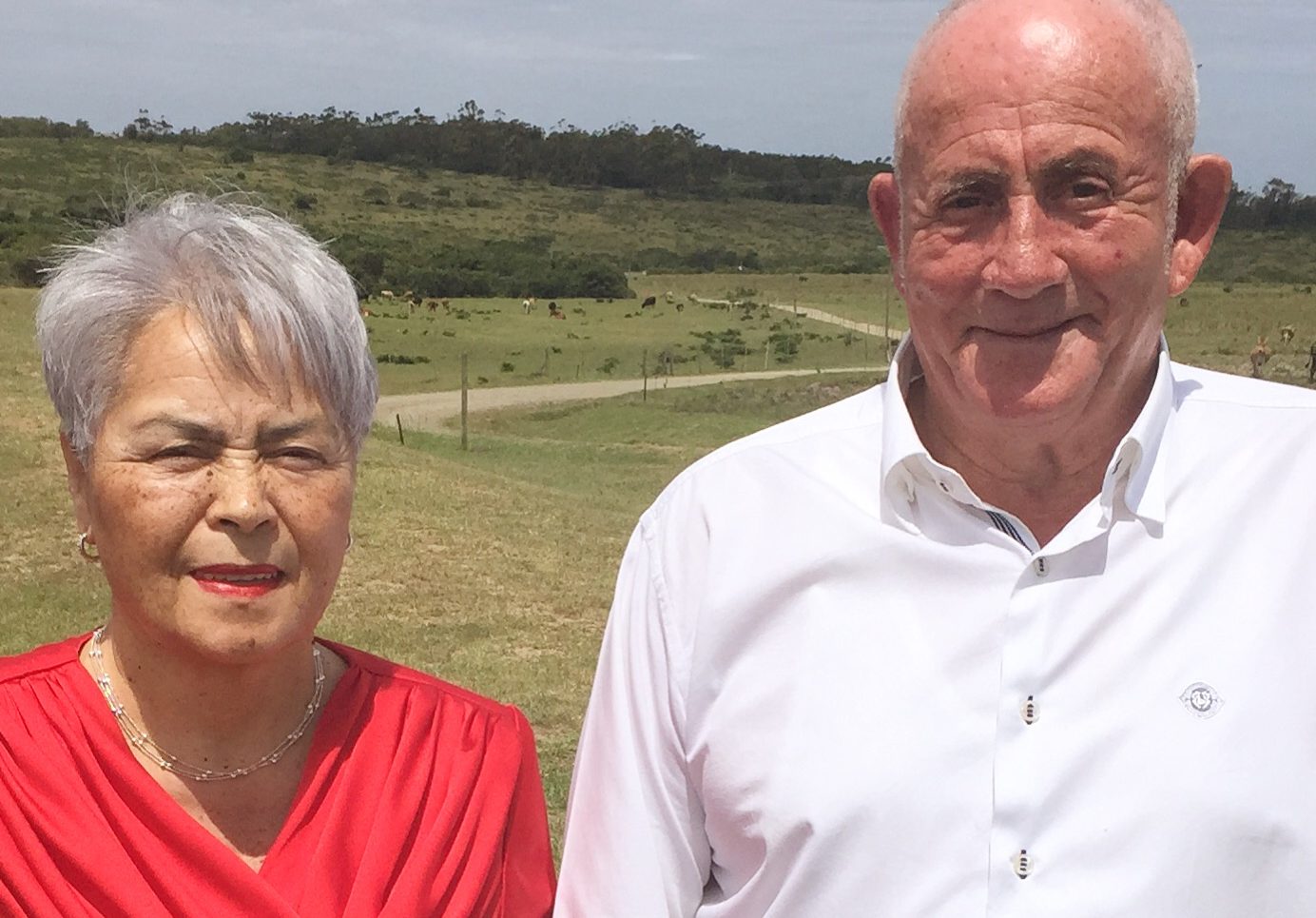

Lionel Bryce-Pease with his wife Erica. Image: Courtesy of the author

My father was a skilled carpenter and a really handy guy to have around any family home. If it needed fixing or refurbishing, Dad was your guy. He would spend hours in his fully kitted garage working on all sorts of projects, often trying to rope me in to lend a hand. It was moments like these where our worlds collided. I suffered from acute sinusitis as a child and being anywhere near sawdust was a big no-no for me. Dad, probably thinking I was a bit of a sissy, would ask me to help with whatever he was creating in the garage, and I’d reluctantly show up – one hand in my pocket, the other holding a handkerchief to my nose. It would be a mere matter of minutes before this body language would send my old man into a rage. It brings a smile to my face thinking about it.

I’d probably make it to about 30 minutes when Dad – probably factoring in my health condition and his one-man skill set – would order me to get out if I didn’t want to be there, or launch into a lecture about how we (the kids) just wanted to sit in front of the television or play cricket in the streets with our neighbours’ children. He wasn’t wrong, but the dust was always no good for my nose, and mom agreed. It was this carpentry mindset – ensuring things were always level or square – that was a kind of madness he brought to all aspects of his life. (That hanky always did the job until the next time he needed me to hold the plank while he sawed through it. I hated every minute of it and I’m guessing he quickly became wise to it.)

My father was a perfectionist even though he wasn’t always perfect. He had high standards and over time we learnt to adjust to his expectations. Dad was great with numbers, as a consequence of his days of learning multiplication tables at school. The introduction of calculators at primary school was anathema to him; he expressed a view at the time that use of a calculator was sheer laziness. He loved to show off how quickly he could figure out the sum in his head, without the benefit of any modern device.

Dad’s car was always spotless. Having a clean, glistening vehicle gave him a huge amount of joy. He used a high-powered hose to wash down the vehicle – which was always parked right outside my bedroom window – at 5am on a Sunday. And when either my brother or I would yell out of the window that we were still trying to sleep and that he was being inconsiderate, the response was inevitably something like this: “Julle wil die heel dag slaap (You want to sleep all day); why don’t you get up and help me?” That silenced us with such immediacy that we quickly learnt to sleep through the man-made rainstorm outside our window.

***

Lionel was born in 1941 in Alice, in the Eastern Cape, the youngest of four children and the only boy. Dad was very articulate about how difficult life was; his father (my granddad, who died before I was born) left home when Dad was in his teens and as the only “man” left in the household it fell to him to leave school after what was then Standard 8 (Grade 10 today) to work and bring in money for the family. When my brother and I were negotiating a new pair of shoes or sneakers or the latest Levi’s jeans, he’d often remind us that they didn’t have such luxuries when growing up and that he often walked to school barefoot. We scoffed, as children do, when the narrative of “When I was a child” emerged from parents or grandparents. We preferred to live in the present.

My father would eventually end up in East London for work, where at some point he would encounter Erica Petersen – the lady who gave me my eyes and freckled nose. She had just one name, Erica, and that made things easier at Home Affairs.

The way Dad told the story is that he would hang out at the shop near where Mom lived in North End, knowing that she would come prancing by at some point, providing him the opportunity to sweet-talk her into the rest of their lives together. Mom insists she wasn’t easy to persuade and didn’t budge for a long time. But Dad’s not here to defend himself so we’ll go with Mom’s version to keep the peace.

I often asked her how and why she chose dad, given that she didn’t lack attention in her heyday. She explained that it was simple: He was handsome and she was thinking about what the children would look like. And so for the sake of her children, she chose the hunk instead of the astronaut. (I’m not sure there was an astronaut so we’ll put it down to artistic licence.)

Dad was always a constant force in our lives. I have no sad tales to share of an absent father. When we had a family gathering he would be the life – or rather, the jokester – of the party. He loved to laugh and to make others laugh. He was a bit of a clown, and as I’ve got older that’s a label that has followed me, too. His passing, due to complications of Covid-19, has led to my connecting the dots, discovering something I hadn’t recognised before.

From showing up at my cricket matches at school to driving me to university in Grahamstown, if he could, he would. My parents would take turns taking me to my weekly piano lessons at the home of the late Bill Sloper in Southernwood. A good report card from my teacher would inevitably lead to something sweet on the way home. I would mimic the sound made by the Toyota Corolla’s indicator – “tick-tock, tick-tock” – just as we were getting closer to Eskimo Hut on Oxford Street. Dad knew this to mean we had to stop and he never disappointed. That soft serve on the way home made practising at the piano all the more worthwhile.

Bryce – as mom and others affectionately referred to my father – was very dependable and reliable, for all members of our extended family. If he was disagreeable or unpleasant when asked to do something (he loved to complain about this aunty or that one who had a husband but still bothered him for help) he’d make up for it by completing the task as only he could – to perfection.

Doing something well was something applied in all areas of his life, including when cleaning the kitchen. We had no dishwasher in those days, so cleaning the kitchen was a labour of love in my home. Dad was the best at it, the rest of us pretenders to the crown. If you did the dishes, ensure that every last drop of water was soaked out of the sink once all the dishes were packed away. Don’t leave as much as a teaspoon draining on the dish rack because that would get you tongue-lashing instead of the “Good job, my boy”. The lashing would be yours, even though the teaspoon might have been the same one he’d used for those four sugars in his coffee. (Yes, four teaspoons.)

My dad was, despite some of his words and delivery, sweet. I recall how he’d share his ginger nuts or lemon creams with me and allow me to dunk them in his morning cup of coffee at a time when we were still considered too young to enjoy our own caffeine fix. Sometimes we’d leave them dipped in for a bit too long, turning his coffee into a biscuit soup. All part of the fun. It’s a tradition I continue to this day, the coffee and cookies, that is, not so much the soup.

We would often joke about how my dad had this uncanny ability to cry at the drop of a hat, particularly during goodbyes when I would leave to travel back to New York where I’ve worked and lived since 2008. Or when we reminisced about someone or something special. He basically didn’t need a good reason to shed a tear. Two days before my departure date, no matter the year, the first indications of an impending deluge would manifest themselves. He would explain that he just had no control over his tear ducts, couldn’t explain it, or wouldn’t, and that we should simply accept it and keep moving.

***

When my dad died, a friend enquired about how my mother was coping and I explained that this was a tough loss for all of us, especially for Mom, who was so looking forward to the celebration of their 50th wedding anniversary later in the year, as was Dad, of course. My friend thought this had been one of those stale, traditional marriages where the woman did all the household chores and that Mom, she explained, would soon embrace a newfound freedom. I looked at the said friend, incredulous and confused, explaining that the marriage had been nothing of the sort.

My father was a modern man in that sense, particularly after Mom had triple bypass surgery in 2009 and almost died. It was as if lightning had struck at his core and he would henceforth overcompensate for her needs, probably, with hindsight, to the detriment of his own. If he did the cooking or the braaing (he was a braai master and an excellent potjie chef in his day) then afterwards he’d do the washing up, too, if I wasn’t around to help.

When Mom’s health became an issue he stepped up as caregiver and we know his absence is even more acutely felt by his wife of almost half a century. They were all things to each other, right until the end – a marked shift from the approach of his own father who deserted his family and denied his only son the means to finish his schooling.

I know one of my dad’s proudest moments was when he donned a brand-new navy suit and drove my mother down to Grahamstown for my graduation at Rhodes University in 2000. We were all bursting with pride but I do wonder what might have gone through his mind when he saw me walk across the stage to be capped. From where I stood I couldn’t see my parents, but I’m sure there were tears, lots of them.

This love affair for his family was on display daily in my young adult life. We texted each other every day. He would ask me the exact time I’d be reporting on the TV news that night, so that he could tune in to watch. Every day, without fail, he’d message. And if I didn’t text, he’d be upset that I hadn’t let him know. And if he noticed that I’d grown facial hair since my last news appearance, he’d comment that it was time to find my blades and shave it clean. Or he’d comment about how good I looked, confirming that I was definitely his son. (…)

My earliest memory of watching rugby was with my dad. Western Province was his rugby team of choice and when that derby happened, it was a big event in my household. Pops would put R10 on the dining room table and because I had no income, the rules were simple: If the Bulls won, I’d get 10 bucks pocket money (the green note with Jan van Riebeeck’s image on it was still good for a sizeable number of Wilson’s toffees in the late Eighties, early Nineties). If they lost, then I’d probably have to do the weeds in the garden or something exploitative of a little boy my age. My team winning and my subsequent taking of money off my dad was the best feeling ever.

Despite my “old man” being such a sensitive bloke, we didn’t talk much about our feelings unless we were having an argument. Gosh, he could argue, a skill he honed when moving in with my mother’s family. He didn’t take things lying down, but as quickly as matters escalated, he was ready to move past whatever had sparked the fire.

Regarding this argumentative side, I recall how my university education was used as a weapon against me – that I thought I was “clever” because I had gone to university. I retorted that had I come back less smart, then what would have been the point of their making all those financial sacrifices to send me there in the first place?

Lionel Bryce-Pease with his wife Erica. Image: Courtesy of the author

Lionel Bryce-Pease seated in his dining room with his sister-in-law, Magdalene Petersen and brother-in-law, Rodney Petersen. Image: Courtesy of the author

The other remarkable thing about my father was that he had no problem apologising and saying he was sorry if he had erred, which he did often enough. That was my dad – snap at you today, cry about you tomorrow.

***

When dad and mom contracted Covid-19 in January 2021, our collective hearts sank. I was in New York so my brother, Laver, flew down from Pretoria to East London to manage the crisis. Eventually, Dad’s oxygen levels dropped so low he needed to be admitted to hospital. It was a complicated situation because he needed to be isolated and that meant no visitors. But he was in a private hospital and receiving what was thought to be the best medical care available, but at a time when frontline workers and hospitals were simply overwhelmed by an unfathomable crush of Covid cases. There’s no question that this had an impact on the standard of care he received.

Mom and Laver drove him to the hospital – and that would be the last time they saw him. Mom sat with him in the back seat on this last drive together; he put her hand on his, in what will forever be their quiet goodbye.

I was lucky to get him on Facetime on a nurse’s phone a few days before he passed. He looked out of it at me, mask on, probably frustrated at having been stuck in this place without his family for days, with oxygen tanks wheezing in the background. I told him we were waiting for him, that Mom was waiting for him and that he needed to keep fighting. He said my name when he saw me – “Hi Sherwie” – and agreed that he would continue fighting the good fight. I took a screen grab of the moment, which is my last picture with my beloved father.

I wish we’d had him longer; we would have celebrated his 80th birthday a month after he passed. We lost a few landmark anniversaries in the process and we mourn the absence of the continuity he represented in our lives. He taught me the value of hard work, to lend a helping hand to others, to be a taskmaster, the importance of sharing and loving selflessly, and he showed me, through his example, the power of an apology. His humility continues to resonate in my heart today.

I might look like Mom but I am Dad’s son to the core.

And yes, I have a dishwasher, which means the teaspoon drains out of sight, just as Bryce would have preferred it. DM/ML

Sherwin Bryce-Pease is a TV/radio correspondent for the SABC at UN headquarters in New York.

Lessons from My Father is a series of interviews and stories collected and written by Steve Anderson. Anderson has been a high school teacher for 32 years, 26 of them at two schools in East London and the last six at a school in Cape Town where he heads up the Wellness and Development Department and teaches English and Life Orientation. Throughout his career he has had an interest in the part fathers play in the lives of their children. He says: “This series is not about holding up those who are featured as being ‘The Perfect Father’. It is simply a collection of stories, each told by a son or daughter whose life was, or whose life has been in some way positively impacted by their father… And it doesn’t take away the significant part played by mothering figures in the shaping of their children. Theirs are the stories of another series!

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

Beautifully written Sherwin.

As a minister of religion, I knew the family well 1981-1986, and would love them to know that I am proud to have known them, and still hold them in my heart, havng followed Sherwin’s career with interest. Dick Cullingworth, retired in City of George, Western Cape.