OP-ED

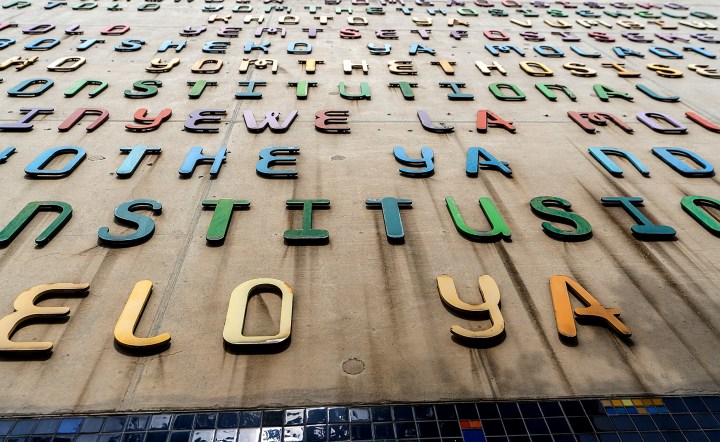

The Constitution at 25 is under attack by violent political language in South Africa

Social media has been harnessed to dismantle our social contract. For example, the language used in the campaign leading up to and during the July unrest was delegitimising and anti-constitutional. This amounts to a trust deficit that needs to be tackled by everyone.

On 12 July 2021, after the most violent unrest in democratic South Africa’s history, President Cyril Ramaphosa said in a televised address: “This is not who we are as South Africans, this is not us”. These carefully chosen words used to describe South Africa have led to a reflection on the power of language when building and maintaining a democracy.

Language can create both positive and negative outcomes, even in the context of the trajectory of a democracy. Juxtaposed with the language of incitement that proliferated on social media before and after the peak of the unrest, the language of the Constitution is one of building, progress and our collective aspirations.

In his paper, “25 years of the South African Constitution: Reflections and realisations”, Dr Klaus Kotzé, a fellow at the Centre for Rhetoric Studies at the University of Cape Town, examines the impact of language on our constitutional democracy. He explores the role of the citizenry in protecting this hard-won democracy from those who would use violent political language to destabilise and delegitimise our constitutional order, including our judiciary.

Kotzé notes the growing audacity that our leaders have in using language in a way that threatens our constitutional ambitions. Language is increasingly used, particularly by our leaders, to misdirect, often away from accountability and transparency. A prime example of this is the repeated public communication about the anti-corruption stance of government, yet we continue to bear the brunt of a government that steals from its people, even during a deadly pandemic.

Kotzé appeals to the employment of sensible language by our leaders and the citizenry at large. He posits that the language of the Constitution is the standard that leaders must aspire to. Every constitutional scholar is introduced to the document as being a living, breathing one that relies on conduct (or restraint) on the part of citizens for it to be impactful. Without this conduct, active participation or buy-in, the social contract envisaged by the drafters of the Constitution stands no chance. While many rely on the right to vote as a way to guarantee a functional democracy led by competent politicians, South Africa has shown just how insufficient it is in the promotion and protection of a democracy. It must also be substantiated by active participation.

As we celebrate the 25th year of the Constitution, revered the world over and a symbol of transition from the old to new, the events of July are a reminder of the importance of the protection and active participation in this social compact. The Constitution can only be powerful and valid if its ideals are practised. The reciprocity in the nature of constitutionalism – the give and take between the Constitution and its people – is fundamental to its existence. Kotzé says we are increasingly seeing attacks on this reconciliatory project. The narratives that seek to undo our progress are mostly populist and unfortunately, effective. But where does the fault lie?

In a discussion facilitated by The Midpoint – a Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung initiative that seeks to create space for conversations about centrist politics – the question of where the fault lies was explored by Kotzé, former Constitutional Court Justice, Albie Sachs and Ongama Mtimka, a historian and political studies lecturer at Nelson Mandela University. Kotzé says that the democracy envisaged in the Constitution was not simply achieved at its birth. It is an ongoing process that requires deliberate, intentional participation from both leadership and the citizenry. He argues that July’s events were a deliberate rejection of the political status quo, therefore, similarly deliberate action must be taken to counter it and rebuild.

I asked him whether this “perpetual state of transformation”, as he calls it, is discouraging for the indigent, to whom this state might suggest a never-ending existence at the bottom of the proverbial food chain. Kotzé says no. Rather, this state was calculated by the drafters of the Constitution. They recognised that the process of transformation is not a one-day war, but an ideal to strive for perpetually. They wrote it into the Constitution as part of the progressive realisation caveat for socio-economic rights, which remain the most contentious of those contained in the Bill of Rights.

Social media has been harnessed to dismantle our social contract. For example, the language used in the campaign leading up to and during the unrest was delegitimising and anti-constitutional. Kotzé argues that if we do not answer this kind of language with equally deliberate, pro-constitutional language, our democracy will continue to corrode. He calls for the employment of respectful communication to repair the trust deficit, with deliberate recognition of the Constitution’s reconciliatory ethos.

Justice Sachs raised the question of rage. For millions of (young) South Africans, the reconciliation is often one-sided. They are the ones called upon to forgive centuries of colonisation and dehumanisation. He notes that those who benefit from this massive exploitation of black people want them to move past it as though the mere existence of the Constitution is a panacea for this collective trauma. His empathy for this contingent that is tired of being polite in the face of those who have everything calling for calm and the exchange of rational ideas, is palpable. His recognition of the exhaustion they feel from living as the eternal students at the table of good manners, is exactly why his contribution to our jurisprudence matters. The people are angry and, in that anger, become targets of manipulation and the kind of disorder we saw with the unrest.

Mtimka expanded on the conversation about rage and astutely pointed out that it is not the mere existence of rage that creates a permissive environment for civil unrest. It is the failure by leaders to deal with rage that does so. The grievances of the citizenry that are not attended to, combined with a political elite that exploits those grievances triggers the kind of unrest we recently experienced.

I asked Justice Sachs if those who are disadvantaged can fully participate in the social contract when they are hungry and unemployed. He said yes, and continued to relate his encounters with the indigent during apartheid. Black people risked their lives by hiding freedom fighters in their homes, carrying contraband pamphlets beneath their skirts and delivering messages, even when they had more to lose than anyone else. Sachs says poor people have the most patience, and that they are only angered when they see those in power abuse them.

But what happens when the poor no longer have patience? When their hunger supersedes their citizenship? It is not what we saw in July?

In his response to the paper, Mtimka, while recognising the commendable transformation process, notes that perhaps we have not properly considered our citizenship and how we conceptualise it together with the burden of social justice placed on us. He says that we are missing bold and affirmative conduct to give expression to the ideals of the Constitution in a way that sees people’s lives changing. He notes the difference between democracy as procedural versus it being substantive. The state’s failure to address the substantive elements continues to pose a threat to democratic order.

When asked what active citizenry looks like, Mtimka spoke to the power of community and how active citizenry takes place every day in black societies in ways that are not traditionally measured. For example, raising a relative’s child, or small-scale farming in remote areas. We need to evaluate active citizenry, using a different and inclusive yardstick. Further, where people are employed, they become capable of active citizenry. Where there is no employment (money), people become preoccupied with bread-and-butter issues and are unable to do more.

A final point of interest was the question of whether our courts should consider the potential for unrest when making rulings. Mtimka says the language used in July sought to intimidate the judiciary so they never again rule negatively against the politically powerful. Sachs expressed confidence in the judiciary and the oath taken to make rulings without fear, favour or prejudice, as they always have. I am inclined to agree with the former Justice – our courts hold a position of respect across the world and intimidation from the political elite is unlikely to unravel their resolve to make uninfluenced decisions.

The aftermath of July indicates, according to Mtimka, that South Africans have become concerned for democracy for democracy’s sake. They no longer care only about their vote as a symbol of substantive democracy. Citizens are concerned about corruption, accountability and the provision of basic human rights. However, when people see and experience the pervasive nature of corruption, populism becomes the order of the day. A damaging kind of language becomes a weapon for disruption and dismantling. When the state has abdicated its obligations to its people, it falls on the shoulders of the people to realise a just state.

From the conversation, one can confidently infer that the language used to fan the flames of the unrest was deliberate and intentional and intended to symbolise or reject the political status quo. So, if we are not a violent nation, then who are we, and can we change? We need to refocus and consider what we want, what we aspire to, and what conduct we must engage in to achieve it.

We have to do the work. DM

Rebecca Sibanda is a constitutional law expert, with a background in human rights and international law. Her experience in the South African constitutional law space includes participation in legislative change, and the monitoring and evaluation of the state’s constitutional obligations to its citizens.

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

Comments - Please login in order to comment.