LESSONS FROM MY FATHER

On persistence and love: Anthony William Haward Mallett

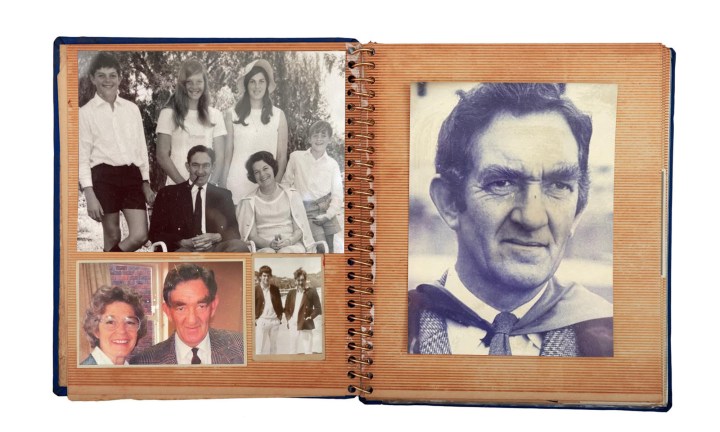

As I look back on my life, I am convinced that the good fortune that I’ve enjoyed has been directly tied to the fact that I had loving parents who stuck together; that my father absolutely adored my mother, and that he set such a great example for us as kids.

As told to Steve Anderson.

Dad was an only child. He grew up in England where his upbringing was a modest one, his father being a municipal employee in a job that didn’t pay a great deal. His mother – my grandmother – had a very strong personality. She was known to be particularly outspoken on women’s rights and was well ahead of the times in many respects.

Gran was also a very sporty woman. Interestingly, she was the first woman in the UK to do the “scissors” in high jump, something that was, until then, a no-no for women in athletics.

Dad had parents who doted on him (and sometimes spoiled him). In sport, he inherited my gran’s genes, becoming a talented cricketer from a very early age. Grandad apparently spent long hours playing cricket with him.

My dad had a very good start to life: He had caring parents who sacrificed much to give him what he needed. And, they stayed together until death separated them. This all gifted him a great deal of stability and happiness.

In 1944, my father went to war, an experience that left some indelible, awful imprints on his memory. One such incident – the most horrific – was his witnessing the death of a fellow soldier who was shot in the back of the head by enemy fire as Dad and eight others were crossing a river in France. For the rest of his life, my dad simply could not stomach the very sight of blood; he would turn sheet-white and would sometimes faint, all as a direct result of that war experience.

After the war, my father attended Oxford University, where he obtained a Master’s in English and Classics. He excelled in sport, getting his Blues for both cricket and squash, and reaching the semifinals of the British Open Squash Championships.

It was at Oxford that Dad met Mom, who was just 21 at the time. She was a fantastic, very attractive young woman, from a family much better off financially than his family was.

Dad was so sure that she – Vivienne Short – was the person he wanted to marry. She, however, had other ideas. The story goes that every three months or so, Dad would broach the topic of a relationship with her. And every time, for a long while, he’d get nowhere. Mom would say: “No no no, I want to broaden my horizons… see more people, meet more men.”

But Dad hung in. He’d reply with: “Vivienne, you are the right person for me, I’m convinced of that; we’re meant for each other; I know we’re going to get together.”

Talk about persistence! Thank goodness he was as persistent as he was, and thank goodness Mom changed her tune. They became a wonderful, loving couple. They became my parents; our parents.

***

I was born in England, as were my two older sisters, Jenny and Tess. At that time my father was a school teacher at a boarding school called Haileybury, in Hertfordshire. After a few years he was offered a housemastership at a rural private school, Peterhouse, in Marandellas, near modern-day Harare, Zimbabwe. I was just six weeks old when my family boarded a ship to start a new life in Africa.

My memories of dad, at Peterhouse, are of his being an extremely active, outdoorsy man, involved in numerous sports, and organising the school’s participation in the “Outward Bound” programme. He simply loved the outdoors.

The school – which was in many senses a farm school – had wonderful facilities: squash courts, tennis courts, a swimming pool, and expansive fields for rugby and cricket. We had the free-roam of the place and I would regularly go watch my dad coaching the boys. He would often get involved in the practices, playing squash or cricket with them, much to their delight. His enthusiasm was contagious, and his skills very impressive. A better role model on the sports fields and courts they could not have hoped for.

My very earliest childhood memory – from when I was four and living at Peterhouse – is of Dad setting up a slippery slide for us in our back garden. It was the kind of slide where a steady flow of water would keep a long, narrow strip of plastic wet enough for us to run up and slide on our tummies for a good 15 to 20 metres. He would sometimes squirt dishwashing liquid onto the slippery slide to make it even more slippery, and our sliding even faster. It was great fun, made even more so by his entering into it all with us.

An awful memory from back then was of a time when my two-year-old brother, Dave (known as D by family members) fell into the school’s then pea-green pool and sank to the bottom. We were playing stingers when it happened, and so nobody noticed that he’d vanished. Suddenly… total panic! Jenny, aged 12, dived into the deep end of the murky green and fished him out of the pool, with some help from Tess and me in dragging him up and onto the concrete paving. Dave was blue in the face, and motionless. I sprinted all the way to the house and yelled to my dad, “Daddy! Daddy! D’s drowned, D’s drowned!”

That frantic, completely distraught look on my father’s face as he bolted to the pool, I will never forget. I can still see it clearly.

When he got to my sisters and our brother, quite amazingly Dave was breathing. Fortuitously – and this probably saved Dave’s life – Jenny had very recently completed a Red Cross course at her school in… drowning resuscitation. In that moment on the side of the pool, she had had the presence of mind and the composure to put theory into practice. Turning Dave on his side, he vomited up gallons of water, and she was able to revive him.

The medics who arrived soon after said to us that had Dave been under that water for just another half a minute, the outcome would have been very different. Thank goodness for that first aid course!

My mom was quite ambitious for Dad. He – like most men, I guess – was happy to hang around in a place where he was happy and content, hoping later to become deputy headmaster of Peterhouse, and maybe headmaster at about 50. Mom would have none of it and she got him to apply for the headmastership of Bishops in Cape Town. That was in 1964. The application deadline had actually been three months earlier; why my mother thought he should send his CV anyway, I really don’t know. He sent it, and actually just forgot about the whole thing. Then, out of the blue, he was contacted by the board of governors. The school had not yet found the right person and he was invited for an interview.

And so, my parents made the long drive down from Zimbabwe and Dad was offered the job, ushering in a whole new chapter of our lives.

***

My father was always a strong believer in tradition and the value of the boarding school system, hence his being persuaded by my mom to apply for that Bishops position. Such was his affinity for boarding, that I’d actually lived, as a boarder, in Springvale House, the feeder school of Peterhouse, from when I was just five. Springvale is in Peterhouse, and my hostel was literally across the road from Peterhouse. I’d just have to look across the road and I’d see my dad umpiring a cricket match. Five days a week, I’d have to sleep in the boarding house, and then head home – i.e. walk across the road – on weekends. It was bloody tough. There were times when I just didn’t understand it all.

Dad slotted right in at Bishops. He liked the focus on discipline, and he liked the hierarchical structure, with juniors looking up to seniors, and “knowing their place in the school”, as was often stressed as being an integral part of the fabric of the school. He believed in all of this, especially for boys, convinced that it set them up well in life and enabled them to get on with other people.

Between the ages of seven and 13 I didn’t have much at all to do with my parents during the week as I was a boarder then, at Western Province Preparatory School in Cape Town, just 5km or 6km from Bishops, where Dad and Mom lived in the principal’s house, on the campus. But we did spend holidays together – great holidays.

Back then, Dad didn’t earn a big salary, and my parents didn’t have a second house which they could have rented out, as many principals these days are able to do. We appreciated the offers by parents of the school to use their holiday cottages, free of charge: We’d have such a good time, playing cricket on the beach, cops and robbers, card games, and other fun activities. My dad absolutely loved this. He’d be fully focused on us – my two sisters, my brother and me, and our respective friends – making sure we were having a great time. I remember thinking then: There couldn’t possibly be a better father.

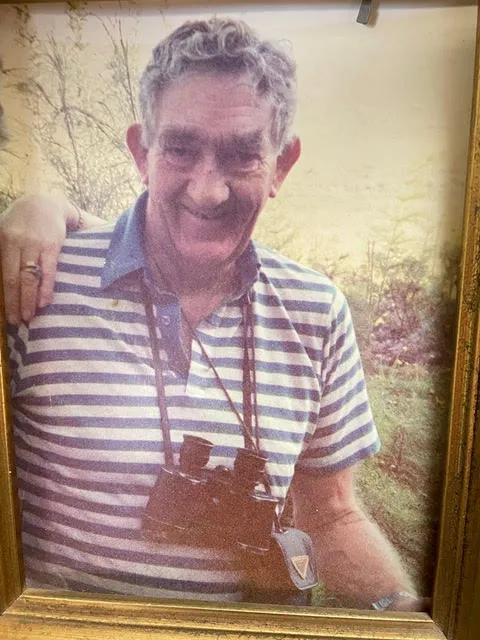

1992: Bird-watching while on holiday. Image supplied by the author.

Something that was really special, and a heck of a treat, was that my dad had this idea that he and my mom should take each of us, individually, on a one-off holiday with them, at a pivotal time in our adolescent lives. So they took my eldest sister on her own with them, then my younger sister, then me, then my brother. My holiday, when I was 14, was to Etosha Pan. It was an incredible experience. Apart from the stunning game drives we went on, we’d have long suppers together, talking about all sorts of things. Dad asked me many probing questions, and got me to explore for the first time what I thought about my next four years at high school, and what life might hold for me beyond matric at St Andrew’s College. Teenagers, especially boys, I think, tend to live day to day, so for me to have an extended time with my parents, being nudged into thinking through who I was and what I wanted for my life, was both formative and empowering.

My Dad had really good emotional intelligence, in addition to his vast academic intelligence and general knowledge. He implicitly understood his children’s differences and instinctively knew how best to navigate them and the challenges they sometimes delivered to patient parents.

Dad was a very tactile person, always openly affectionate. Once, after driving 10 hours to come see me in high school, I’d run across the car park, super eager to see them. Dad and I would meet halfway, and he’d throw his arms around me, giving me a huge hug and a kiss. When this first happened, my friends reacted in utter disbelief, later saying to me: “Mallett! Do you let your father kiss you?” – as though that was the most unbelievable, revolting thing in the history of mankind for a teenage boy to do. I replied, simply saying: “Of course I do. A handshake is just not good enough when you’ve not seen your dad for a long time.”

***

My siblings and I learnt so much from my father about what he viewed as important in life. One thing about him – which on occasion caused some embarrassment to the family – was that he placed no importance at all on things of value. For many years he drove an old, clapped-out Peugeot 404. It was almost completely rusted through, to the point where he was at risk of slipping through the vehicle and landing himself on the tarmac! (okay, not quite so bad) Despite the visible-to-all rust, our father saw no need to replace his Peugeot.

To him, what was of utmost importance was people, and the characteristics of each person. Was the person kind? Was the person thoughtful? He was all about teaching and nurturing good values, and his best teaching was through his example, through his role-modelling. Fancy cars and expensive restaurants were simply not on my father’s priority radar.

Dad also taught us that in life there are two choices: You either cook or you do the washing up! Now one of his weak points was that he didn’t cook. And he was hopeless at braaing. In the kitchen, the best he could do, really, was fried egg and bacon. So, in the many years that we were at our respective boarding schools, Mom cooked and Dad, he washed up.

But the single most significant impact my father had on my life is: He absolutely adored my mother. So much of what I’ve been gifted in my 65 years is rooted in his unwavering love for my fantastic Mom. From an early age it was abundantly clear to us as children: Mom was Number One. On a “level below” were the four of us kids.

When Dad would get home from work he’d come through the front door, calling “Darling, Darling!” always eager to share with her the news of his day, and to hear hers. If there was no reply to his calls, one could sense his worry, as he began his walk through the house to find his soulmate.

Yes, they did fight, occasionally, but even in the big arguments the strength of their love for one another was still so evident. There was never a whiff of a possibility that arguments and disagreements may lead to separation. And Dad would never, never have raised his hand to Mom. Never.

Once, I must add, Mom did throw a pillow at Dad. But that’s another, funny story.

My parents formed a fantastic, formidable partnership. They shared everything, and Dad would listen to Mom’s opinions and regard them above those of anyone else. Even his speeches for school functions: She’d sometimes say things like: “Ant, you’ve forgotten to thank (Person X)” or “I think you’ve given too much credit to (Person Y)” or “you need to make it clearer that…”

Some people in management choose to “go at it alone” and not involve their partner at all. Not Dad. In his typically humble way, and through his respect and high regard for our multitalented mother, he took on board her insightful suggestions and opinions, and he did so all for the good of the school he ran, and the boys in his care.

Colon cancer took my dad when he was 70.

He was a truly wonderful father. His deep love for my mother gave me such a sense of stability, and his sensitivity to my needs – indeed, to the needs of all his children – nurtured and instilled confidence in me, for which I am hugely grateful.

I was fortunate. Very fortunate. DM/ML

Nick Mallett is a former Springbok rugby player and Springbok coach, and current SuperSport rugby analyst.

This story has been edited slightly.

Lessons from My Father is a series of interviews and stories collected and written by Steve Anderson. Anderson has been a high school teacher for 32 years, 26 of them at two schools in East London and the last six at a school in Cape Town where he heads up the Wellness and Development Department and teaches English and Life Orientation. Throughout his career, he has had an interest in the part fathers play in the lives of their children. He says: “This series is not about holding up those who are featured as being ‘The Perfect Father’. It is simply a collection of stories, each told by a son or daughter whose life was, or whose life has been in some way positively impacted by their father… And it doesn’t take away the significant part played by mothering figures in the shaping of their children. Theirs are the stories of another series!

[hearken id=”daily-maverick/8901″]

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

Great testimony to your Dad Nick.

Brought a thoroughly good man vividly to life. A great example.. thank you.

Lovely!

Such an excellent series this!