MUSICOLOGY

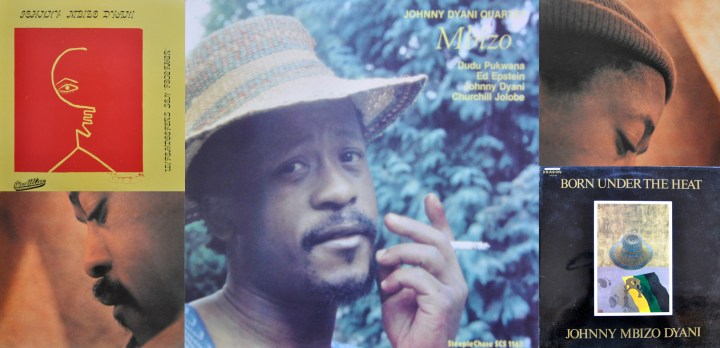

Johnny Mbizo Dyani: Genius, mystery and Afrofuturism through bass

November 30 marked what would have been Blue Note member Johnny Mbizo Dyanis’ 76th birthday (some say 78th) — here, I take a journey through conversation with the living and departed jazz musicians and students on impression of the Afrofuturistic bass master.

Afrofuturism addresses themes and concerns of the African diaspora through techno-culture and speculative fiction, encompassing a range of media and artists with a shared interest in envisioning black futures that stem from Afro-diasporic experiences. While Afrofuturism is most commonly associated with science fiction, it can also encompass other speculative genres such as alternate history Afrofuturism within music represents a diaspora of music that is non-traditional, focusing around the topic of blackness and space.

Like Sun Ra before him, Dyani is also an Afrofuturist, as they both share the similarity of recording music which created a new synthesis using Afrocentric and respectively space-themed and segregation-less titles to reflect their linkage of ancient African culture (Egyptian for Sun Ra and isiXhosa for Dyani) and the cutting edge of the Space Age. For many years, they both worked and performed in the diaspora as it were while promoting Afrofuturist ideas by touring festivals worldwide.

The mystery of the man also adds to the genius. There is talk that the often volatile young Dyani only found out at the ripe age of 20 years, and after travelling across four continents, that his Dyani identity was adopted by a family from Duncan village (iziPhunzana) two years after his birth in 1945. This is miraculously after his biological mother lost her life giving birth to Dyani and his two twin brothers in a village outside of Zwelistha, KingWilliamstown, circa 1943. The other two infants perished with their mother, but Johnny Dynani survived. It is noted that once he learned about this truth, as he was still in Europe, his spirit and character seemed to get more unsettled, yet his music was as moving. His refusal to be displaced mentally whether because of his own family history, or his diasporic reality allowed him to be both shrewdly critical of his fellow musicians, and also connect with his spiritual convictions. The ‘Mbizo’ in his name was only added after he learned his biological truth. Mbizo is supposedly his paternal father’s name; apparently, the witchdoctor’s son’s pseudonym got its life from here.

As mentioned, his critique of his colleagues was sharp. He made a statement once, appalled by diasporic musicians working for European bands: “I’m trying to work for Africa so that Africa can work for me…Where the other cats are concerned the instruments are playing them, instead of them playing the instruments. I mean, I refuse to be played by an instrument.” His Afrofuturism was clearly already at play, as young as he was, he had a mature aura. Eclectic.

Many countries were sympathetic to the struggles of South African artists in the 1960s’, but ‘Uncle Sam’ was by far the most impactful, in as far as magnifying the fall of the apartheid regime. You could say that the more conservative artists chose the Scandinavian and European windows of opportunity to free their jazz as it were; Mayibuye and Amandla productions come to mind. Mayibuye, an agitprop group that achieved considerable success in Europe in the 1970s; and Amandla, which travelled widely as a liberation movement ambassador during the 1980s, offering large-scale performances incorporating music, theatre, and dance. Both ensembles made contributions to the development of somewhat cultural activity and yet remain virtually undocumented in the history of the movement and the struggle: how black South African popular culture came to play a role in the anti-apartheid movement’s work in exile, how it was recruited and re-packaged in order to appeal to foreign audiences, and the relationship between this and cultural activity that was more internally focused.

The more charged-up protest artists by default were to be attracted by the environment of the civil rights movement in the United States as well as the pop culture value that their music could suckle from.

The Woodstock festival and the New Orleans jazz culture were just some catalysts that would keep exiled musicians energised in the wilderness of being detached from their own. The usual suspects Abdullah Ibrahim, Pops Mohamed, Miriam Makeba, and Hugh Masekela were naturally attracted to civil rights movement-linked entertainers. The latter duo is contemporaries Belafonte and Coltrane. By the mid-1960s, John Coltrane was at the height of his career and already established as the guiding light of a new form of avant-garde jazz that was upending traditional ideas of just what was jazz music. At the same time, huge cultural and political shifts were underway in the form of the civil rights movement, which sought to break down the existing social order. Evolving in parallel and informed by similar cultural and historical touchstones, the civil rights and avant-garde jazz movements both informed and influenced each other.

The time also produced Miles Davis and Nina Simone on that same side of the world, who were every day of their professional careers blurring the lines between white and black restrictions, operating in grey areas. Simone’s entire life was a struggle for freedom which she achieved in many ways by breaking conventions of race and genre. Her legacy is ongoing, with her music still in popular demand and being sampled by artists such as Kanye West and Lauryn Hill. Little Girl Blue continues to fight for freedom from beyond the grave.

Their South African counterparts needed this, for their voice was not free. Makeba went on to use her links to address the United Nations on matters of injustice in South Africa that the Herrenvolk media was surpassing and world leaders ignoring. Those that trickled in in the 70s and 80s in particular, were also in the midst of mastering the ‘fowl run’ on the music scene in America whilst fighting apartheid from afar, carving their own identity of South African Jazz, a jazz of masters of studying civil rights movement triggered American Jazz greats.

The Blue Notes are the most significant avant-gardists in this case. Johnny Mbizo Dyani, Mongezi Feza and Louis Maholo, and others like pianist Tete Mbambisa (whose achievements until recently have been hidden from jazz history). They were music geniuses. Dyani suckled music from Tete in the dusty shantytown streets of iziPhunzana (Duncan Village).

The latter, born in East London’s Duncan Village in 1942, learned to play the piano his mother had put in her modest shebeen. He credits the place’s pianist, “an old man called Langa”, with teaching him his first chords along with listening to his brother’s record collection, being influenced by the likes of Frank Sinatra, Louis Jordan, and the Four Freshmen, a ‘pure fowl runner’. As the pianist with the Jazz Giants, he took a prize at the 1963 Cold Castle Jazz Festival and by 1969, was working with Winston Mankunku and playing, composing, and arranging with tenor-player Duku Makasi’s band, the Soul Jazzmen, on the landmark album ‘Inhlupeko’. The composition Black Heroes, which first appeared on his only big-band album, ‘Tete’s Big Sound’ is one of the biggest hits to happen to the South African jazz scene of the 1970s) and Retsi Pule picked up the baton.

Eric Nomvete also comes to mind because his Eastern Cape-East London roots were at the heart of a Jazz culture of protest that was exiled in the wave of globalisation, which would use smart bush guerilla missions to outsmart the apartheid system in South Africa using music.

In an unpublished article, Sinazo Mtshemla interprets a 1985 interview with bassist Dyani by Aryan Kaganof and clarifies that: “Although Dyani does not directly link this to the fowl run, I would like to suggest that it is him explaining how the fowl run works in a performance. Here he is talking about the wide range of records that the Blue Notes had listened to in South Africa that Europeans did not seem to have been exposed to, which were the great American musicians such as John Coltrane, Booker Ervin, Charles Mingus etc. Interestingly, Dyani sees their practice of doing the fowl run as comparable to guerrilla tactics of confusing the enemy so to speak. It’s as much a question of playing with the feel as is a political act. Carving a new path that will not be recognisable and will not be attributed to American or European influences but as their own thing.’’

Mtshemla goes on to allude: “This leads to the point that the fowl run, as can be understood when it takes on the sound of free jazz, has its roots as much in Africa as in the United States. The fowl run, he suggests belongs to the ‘Family of Black Music’.”

This is a raw fact. Back in South Africa, the fowl run was out at play. Unlike abroad, the music like the political opinion was still under the yoke of segregation laws. So the entertainer went underground. Into the Bantustans that were squeezed, or hidden deliberately in pockets of the Apartheid Republic, with unclear ceded zones that allowed room for spontaneous activity: East London, Mdantsane in particular, was the hub; with offshoots of Port Elizabeth and Queenstown feeding with ease. Not the flashy bars and motley crew-infested bars in Chicago, but the Townships, Zwide and Ezibeleni.

From the 1950s, the black townships spawned every conceivable form of communal performance: Sophiatown, near Johannesburg, produced particularly creative musicians and dancers, not to mention the literary brilliance of Lewis Nkosi, Nat Nakasa, and Bloke Modisane. There were trade union performers, Johannesburg’s Junction Avenue Company, Kessie Govender’s Shah Theatre Academy in Natal, Grahamstown’s Ikhwezi Players, Rob Amato’s Imitha Players in East London, and others. All were legendary, all were harassed or snuffed out.

In an interview preparing for a music radio show with savvy jazz vocalist Sakhile Moleshe, I was invited to the now late East London-born bassist and true avant-gardist Lulama Gaulanas’ home cum time-travel archive of SA Jazz Culture in Mdantsane. On that particular day, I find him with Ayanda Sikade (a drummer on steroids in our lifetime, genius), Gaulana reflected that he was a budding youth in Mdantsane in the late 70s and early 80s when the golden era was at its peak. Like his understudy Sikade towards him, he looked up to the likes of Dyani. He even has a story of how his current bass guitar is said to have been Dyanis’ before, only to find out because of the ‘Family of Black Music’ culture of the time artists would share some hygienically-allowing instruments. The guitar was not his, he once played it in an underground concert, that’s all. We had a good chuckle about that, and how he would use that story as leverage when he feels like it.

Gaulana points out that because of the arrested nature of protest art, many musicians, actors, and journalists descended on the townships in the outskirts of the Republic. Many of the King Kong brigade who came back from exile, had no other pocket to jump into but the underground, as the international world had no say in the apartheid state. A certain Zimbabwean-born Dorothy Masuka, through her King Kong exploits and Tete Mbambisa connections with the Soul Jazzman, often ventured into the homelands on the fringes of the Republic to play ‘free’. No neutral clubs, no industry but the dusty shantytowns, where social strife was exorcised with the devil’s music, Jazz. See jazz became a language more than a genre. It became a weapon that exposed the fallacy of racial categories.

It is this weapon we saw in the late Zim Ngqawana when he coined a new form of protest philosophy in music, Zimology. We see it in the explosion that is Sikade on drums when he plays with the Nduduzo Makhathini trio. It’s the very same Blue Notes and Dyani propelled ‘fowl run’ that made bebop look like an infant when it comes to challenging the status quo. It’s the very weapon that embodies the zeal in Kesivan Naidoo and Feya Faku when they are rainmaking at the Birds Eye in Switzerland. The electricity in Siya Makhuzenis’ trombone call, its home, this weapon, is the cry of freedom for the homeland. Free Africa with Jazz. DM/ ML

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

Comments - Please login in order to comment.