LESSONS FROM MY FATHER

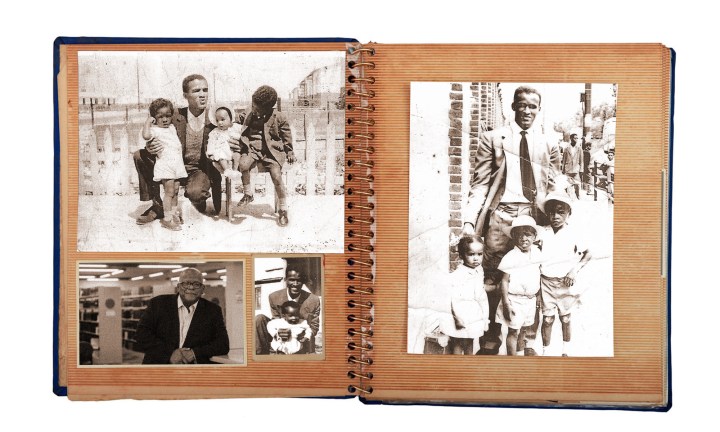

A life and duty in faith: Abraham Christian Frederick Jansen

Abraham Christian Frederick Jansen, or Abie as his friends called him, made up the gentle, generous, and gregarious parts of me that I am thankful for with the gratitude that comes with growing older.

Abraham had a tough life growing up. His mother died when he was a child. His father was an alcoholic. In the wood-and-iron home on Denver Road, Lansdowne, it was by all accounts a very difficult job for his father and stepmother to raise six children and a couple of adopted boys as well. There was a harshness to their upbringing, like the often-told story when his siblings were visiting about how my grandfather put the hand of one of his children onto the hot oven plate to teach her a lesson about touching hot stoves.

Abraham married Sarah who gave birth to Isaac. A story straight out of the Old Testament. All of us but one had biblical names starting with the eldest (Jonathan) followed by Peter and Naomi. Denzil was named after the madam’s son for whom Abraham worked as a domestic at one stage in his life. The biblical name-giving of the children was the result of Abraham and Sarah becoming born again, instantly turning Anglican and Dutch Reformed Church believers, Abraham and Sarah respectively, into evangelical Christians. They certainly lived the life and duty of faith in everything they did.

From Abraham, I learnt that invaluable competence for any boy called impulse control. When Denzil died on his 21st birthday after a horse ran into his car on one of the dark streets of Philippi, Abraham received the news by telephone, called the family around him, and sank to his knees to thank God for his departed son. Abraham always prayed on his knees, not deeming himself worthy to stand before the Almighty. It’s those little things you observe growing up that teach you humility and respect for the divine. I learnt much from this humble man, including how to estimate oneself.

My primary school marks were average at best. So, when I one day got 100% on some test, I ran home to tell my father. It was a Thursday, the one day of the week on which he came home early from his job, at the time as a driver for Nannucci Dry Cleaners. On those days he would make a hot curry for dinner and join us for a few kicks on the open field next door where the boys played soccer. On this day, however, I was waiting for the green and white van to arrive to show off my test paper.

Abraham came, walked straight past me, took the paper being waved, and made himself some coffee and read the Cape Argus at the small table in the kitchen. After what seemed like a very long time, he looked up at his eldest child, smiled slightly, and returned the paper with these unforgettable words: “There is room for improvement!” I was devastated. Years later I understood the message: even when you are doing your best, you can do even better. It is the source of my continuing crusade in schools and universities — you are smarter than you think; set high standards and do everything in your power to exceed them. It is what I still do to this day in my own life as a professor.

Not once did I hear Abraham fight with my mother. Like all couples they had disagreements, but they would talk it out and the children would hear everything. I remember the first time I saw a man beating his wife; it was traumatising, for I had never seen such behaviour in my family home. In the community and the evangelical church where he was an elder for some time, Abraham was known to be the peacemaker.

It was in church where I learnt much more about Abraham. Though he had only finished the Junior Certificate (JC or Standard 8) at Livingstone High School, that was quite an attainment in those days. It was in the church, however, that generations of men learnt to read, write, and do public speaking as lay preachers. They preached from the pulpit, in the streets and on the trains. Grown men would learn to memorise scores of their favourite texts and how to analyse scripture through a dispensational lens. They built their reputations as fiery preachers of the gospel or as solid teachers of the Word.

Abraham was not a very confident man in daily life but when he took to the pulpit, he was unrecognisable. He preached with passion, eyes closed, and his voice rising and falling for effect. How he could recite scripture and verse with such accuracy, from Genesis to Revelation, is still something of a mystery to me. From the fiery lessons of Abraham, the preacher, I would come to learn how to speak in ways that capture and hold the attention of an audience. I also learnt that a message with two or three hard-hitting points was more likely to leave a mark than a long, rambling, and unfocused speech. And I learnt not to try and be too clever but that a simple, consistent message was the key to communication with any audience.

Professor jonathan D Jansen. Photo: courtesy of the author

Most of all, I learnt from Abraham the meaning of transcendence. That you live for something bigger than yourself. That there is spiritual life beyond your mere material existence. And that it is better to give than to receive.

Abraham had chosen to spend the last years of his working life as a missionary in the Karoo. He lived in a small, borrowed caravan. One day he was making his favourite doughnuts and somehow the hot oil fell onto his body and burnt his back badly. He lost his senses for a while, but Sarah, a nurse by profession, brought him back from the mental hospital to normal life and living. Recovered, Abraham went back into the mission field from time to time.

On one such visit to the remote Northern Cape town of Strydenburg, one of the locals told me that Abraham was out sharing the Word with other locals on a Sunday afternoon and inviting them to the gospel service that evening. A man said he did not have a decent shirt to be able to attend the service. Abraham promptly removed his own shirt and gave it to the invitee, exposing his burnt back.

That’s my Dad, and I am immensely proud of him for teaching me things that school and university did not. DM/ ML

By Professor Jonathan Jansen – Distinguished Professor of Education, Stellenbosch University. Former Vice-Chancellor of the University of the Free State; Distinguished Alumnus, Stanford University.

Lessons from My Father is a series of interviews and stories collected and written by Steve Anderson. Anderson has been a high school teacher for 32 years, 26 of them at two schools in East London and the last six at a school in Cape Town where he heads up the Wellness and Development Department and teaches English and Life Orientation. Throughout his career he has had an interest in the part fathers play in the lives of their children. He says: “This series is not about holding up those who are featured as being ‘The Perfect Father’. It is simply a collection of stories, each told by a son or daughter whose life was, or whose life has been in some way positively impacted by their father… And it doesn’t take away the significant part played by mothering figures in the shaping of their children. Theirs are the stories of another series!”

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

Comments - Please login in order to comment.