REFLECTION

Des & Dawn: The lives and times of an inseparable duo

A new book by Des and the late Dawn Lindberg is a captivating and highly entertaining must-read about so much that has happened in South African theatre, music and the related politics of the decades from the 1960s to the present.

Banned! Blasphemy! Obscenity! Banned again! Kommie vuilgoed! Godspell banned! Rooigevaar! Swartgevaar! Sies! We’re obviously talking about diehard subversives involved in sedition, agitation, insurgency or worse, right? But folk singers? Whose repertoire includes Puff the Magic Dragon and This Land is My Land? Oh, mind you… puff … the magic dragon. Ah. Maybe that’s what it was all about.

Those opening slurs and many others were among the “notices” Des and Dawn Lindberg received during their careers in music and theatre. The duo even had their album banned. A folk album! Because they stood up against the status quo, and stood for what was right and worth fighting for. Des and Dawn Lindberg were more than just a pair of cool folk singers, sweet and lovely as their music was. There was steel in their spines. But through it all, they were together. Des and Dawn were always together. Which is why it is hard to write this now, with Dawn gone; Des is still here, but without his Dawn.

They even met during a protest, depending on who is telling the story. Picture the scene: the Wits campus, February 1962. It’s a protest march against 90-day detention. The students who have assembled at the Planetarium at noon include a 16-year-old freshette, Dawn Silver, who was “full of energy and fire to be involved with student politics”. She’s excited and nervous, the very emotions that go hand in hand for every actor, director and singer having to perform on stage or direct a show. These are feelings she will know all her life.

As the clock strikes 12 the students set off. Dawn Silver, sweet 16, is right in front with other students and powerhouses of opposition politics including Helen Suzman and Zach de Beer, sundry clerics and Black Sash members among hundreds of others. In silence, and peacefully, 20 abreast, the march leaves campus and proceeds onto Jan Smuts Avenue, over the Queen Elizabeth Bridge and on through the CBD towards the City Hall.

Des picks up the story: “Traffic is diverted. Groups of workers line the route and cheer us on, but soon move back as a convoy of buses arrives, spewing out what seems to us like squads of large, hostile young men in shorts, and robust young women at their elbows, yelling invective slogans: Weg met Witsie liberaliste! Rooigevaar! Swartgevaar! Hardloop Kommie Vuilgoed! Ons gaan julle iets vandag leer!

“They form up like rugby lineouts and back lines, and start a menacing advance on our frozen group. They are joined by equally menacing reinforcement from the old Post Office across the road.”

In the melee, gas mask-clad cops with riot shields and brandishing sticks pour out of vans and tear gas canisters start landing among the protesters.

“My throat burns and I can’t see through the choking haze,” Dawn writes. “The march disintegrates with students, clergymen, and politicians running in all directions trying to make it across the library lawns and up the steps into the safety of the library foyer.

“Through the fog, I see a huge Tukkie student right in front of me, his arm raised with what looks like a sjambok in his hand. I try to scream but no sound escapes from my clogged throat. I close my eyes and freeze. Suddenly I feel an arm shielding me from the aggressor, and a figure clad like some wizard in an academic gown blocks me from the attack. I can just make out my protector’s other hand raised holding a pole wrenched from the banner I’ve been carrying, and I hear a thud as it comes down on the back of one of the fleeing assailants… ”

Seconds later the two strangers burst through the library doors. “His gown smeared with tear gas smoke residue, and the banner pole still in his hand, my bodyguard grabs a paper cup from next to the water fountain, splashes my face and dabs my smarting eyes with his long flapping sleeve. I blink up at him, bewildered, still a little in shock after this first taste of violence in my sweet 16 years.”

“Hi, I’m Des,” the man says, and the rest, well, we know what comes next.

Along the way is a pair of lives so storied that the book they have now produced, though sadly after Dawn having left us thanks to Covid, is a revealing and thoroughly readable account of the times of so many of our lives. I found myself cross-referencing from the index to chapters here and there, and each time, after only two or three words, I’d finally look up and see that I had read 10 or 15 pages. It is that readable, fascinating, and well told.

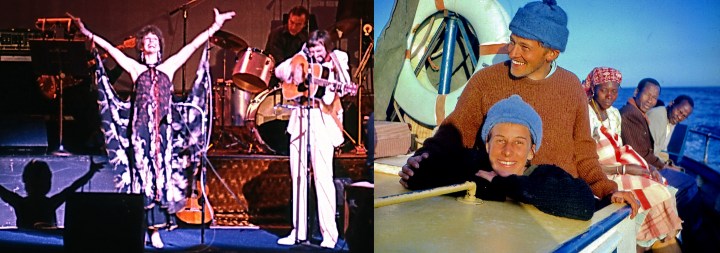

Before the final chorus when performing Die Gezoem van die Bye live, Des would ‘pull his mouth downwards and do a wicked satirical impression of BJ Vorster talking drivel’, writes Dawn. ‘Pieter-Dirk Uys years later told us it was Des who’d inspired him to start impersonating politicians…’ (Photo: Supplied)

With all the brilliant theatre-making they have done in the decades of their lives, we may sometimes forget that they were folk performers first, with albums, tours and all the drama of their unlikely bannings that went with them. Much of their output was innocent but they were never shy to kick against the pricks, and you may read that both ways.

One story, in particular, celebrates their chance-taking spirit and says a lot about why they were so very successful in many and varied ventures. They simply put themselves out there, as we would say today. It’s 1965 and they’re on holiday in Durban, wearing shorts, T-shirts and sandals and strolling along the promenade. Opposite them is the grand Edward Hotel with its posh Causerie nightclub. Out of the blue, with his cheeky grin, Des dares Dawn: “Do you want to know what it feels like to be thrown out of a posh hotel? Let’s go into the Edward and ask for a gig.”

Des writes: “We strode confidently into the cool marble lobby and were immediately confronted by a haughty doorman in pin-stripe trousers and a tailcoat who was looking askance at our attire. ‘Can I help you, sir, miss?’…

“We’d like to see the manager.”

“Your names?”

“Lindberg. Des and Dawn Lindberg.”

“‘Wait over there please,’ said the doorman, ushering us to the furthest corner of the lobby. After what seemed like an age, he returned, looking somewhat nonplussed. ‘Mr Gottkens will see you now.’

“‘Des and Dawn, what a surprise,’ said Fred Gottkens.”

Turned out the hotel manager knew the old Troubadour in Joburg very well and had seen several of their turns at the old Doornfontein haunt. On the spot, he offered them a two-week cabaret stint at the Causerie starting that very night for “R200 a week plus dinner and a room”. It was their first-ever cabaret gig. They went shopping for a cerise mini dress and gold sandals for Dawn and black bellbottoms for Des. He borrowed a white shirt from an uncle in Windermere Road. The local papers gave rave reviews to “Des and Dawn Langridge” – not the last time people would get their name wrong.

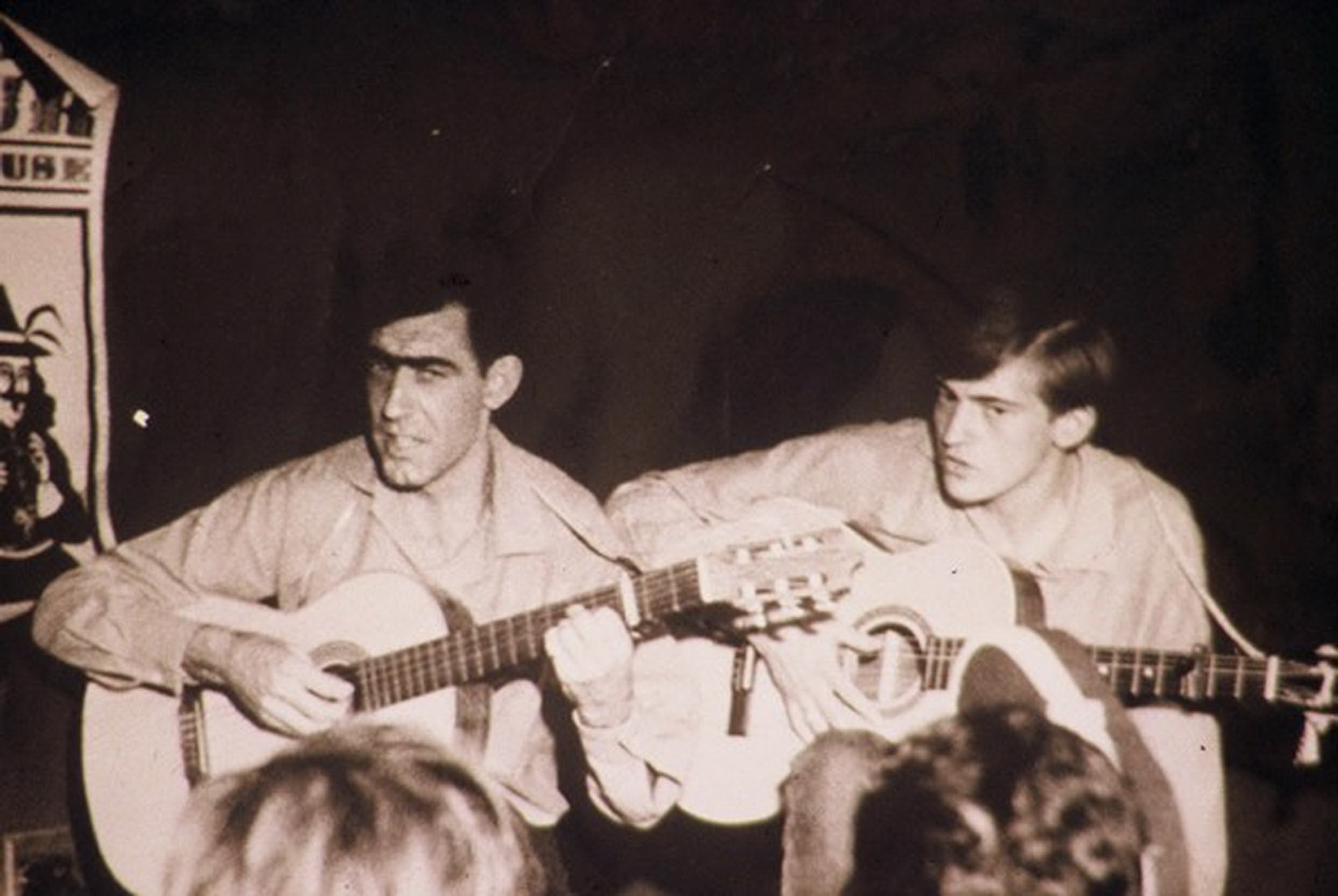

Keith Blundell and Des live at the Troubadour. (Photo: Supplied)

Des with Ian Lawrence (R) at the Troubadour. Dawn had first thought Lawrence, at 32, too old to perform at the venue, but became ‘one of the most popular acts we ever booked’. Blundell and his family were a massive force on the SA folk scene and had partnered with Des to form The Bottletops. Tragically, he was paralysed in an accident in the 1980s. He died in 2002. (Photo: Supplied)

The Troubadour was famous throughout the land in the day as the hub of the country’s folk music scene. It’s 1964 and the chapter in the pair’s new book, Des & Dawn, Every Day is an Opening Night (our journey together), is entitled The Troubadour in Doornfontein: Folk Headquarters of South Africa. It was to folk music what Ellis Park is to rugby or Newlands to cricket. The Troubadour had sprung from the premises of a gay club called the Pianola. Des was already a known fixture on the city’s folk scene, and was approached by the new owners to run it as a folk club for 10% of the profits.

Dawn plastered a wall of the little house black, painted bright yellow over that, and gouged a sgraffito Medieval scene of castles and fiddling knights on horseback courting voluptuous damsels in keeping with the Troubadour theme. When no one pitched up the first week, Des sent a gaggle of folk singers off to the new Cinerama down the road and into town to the Colosseum with the injunction: “… as the people come out of the movies, go up to them and hand them this roneo’d slip of paper with the address and the offer of free coffee and folk songs at the Troubadour… Offer valid for one week only so tell them they must come now!”

Come they did. What they must have thought of the cuisine is another matter. People would arrive with their own Tassies and Lieberstein and they’d charge R1.50 corkage, “and a folk shebeen was born”, to quote Dawn. The cover charge was R2 and you could get half a baby chicken in a basket (a very Sixties thing) for 45 cents and 25 cents more would get you chips too. A T-bone steak and chips was 75 cents, spag bog 50c, and a “Unicorn Float” was 45c.

A Unicorn Float? That was a Chocolate Log floating in guava juice with cream on top. And no, nobody has ever heard of one of those since. I hope.

Their very next break after the Causerie in Durban was at the Royal Agricultural Show in Pietermaritzburg’s Alexandra Park where they did some of their favourite shows ever to appreciative crowds. My wife has a photo of her 16-year-old self at the 1966 show with her friend Barbara. Writes Des: “We returned there three years running, packing the stands with bigger and bigger crowds, and performing between the judging of the sheep, auctioning of the bulls, and the Army’s motorbike daredevil display.”

Dawn playing guitar during their ‘prenuptial honeymoon’ on Inhaca island off Mozambique, 1964. (Photo: Supplied)

Des and Dawn on the beach. (Photo: Supplied)

Des had had a career of his own before he and Dawn teamed up professionally and became the inseparable Des & Dawn. In 1964, Des recorded his debut solo album, A Long and Dusty Road, which won a SARI award. But one of the songs he remains best known for was Die Gezoem van die Bye (that’s the Afrikaans plural of bees, not bye-bye), his Afrikaans rewrite (with Louis Combrinck) of Burl Ives’s American hit Big Rock Candy Mountain. How the song came about was as random as it gets. In Mozambique on a sneaky getaway without the teenage Dawn’s parents’ knowledge, staying in a pup tent on a beach, they heard raucous singing. Des went to investigate and encountered a group of beer-swilling Tukkies students singing Big Rock Candy Mountain but with an Afrikaans chorus. He joined in, Dawn did too, shyly, while hoping they weren’t the same students from the infamous protest. Back in their pup tent, “with notebook balanced on his knees, he wrote most of the Afrikaans lyrics for which he was later to become famous”, writes Dawn. It topped the Springbok Radio charts for 20 weeks and won him a gold disc.

My personal favourite though is 16 Rietfonteins. When I’m on a long road and I pass yet another sign to Rietfontein, 16 Rietfonteins always pops into my head and stays there for the remainder of the day’s drive. It’s the perfect South African road song, the names of the towns representing all of us, because that’s who they were and how they saw us all: united, sharing.

Their most famous though was 1971’s The Seagull’s Name was Nelson, written by a British music promoter, Peter E Bennett, whose own version had, as Des wryly observed, “failed to fly”. There’s a riveting tale about this recording, its success, and music industry machinations, but I can’t tell every story from the book here so that’s one for dipping into if you buy it.

As a teenager in the Sixties, I knew Des Lindberg’s songs and later his and Dawn’s, but it wasn’t until I had become an arts writer for Cape Town newspapers that I first met them. I’d been flown to Joburg to attend rehearsals of their new show for a week, and on the first morning I arrived in neat suit and tie, not my metier at all but what I’d thought would be required. Sitting to one side, Dawn introduced me to the cast in their sweats and leggings, me feeling as out of place as a nun at a bikers’ convention. Next day I arrived in jeans and T-shirt and felt much more in tune with things. Dawn was a vision to behold when directing a large ensemble cast. Exacting, strong of voice, direct of eye, she commanded with a smile.

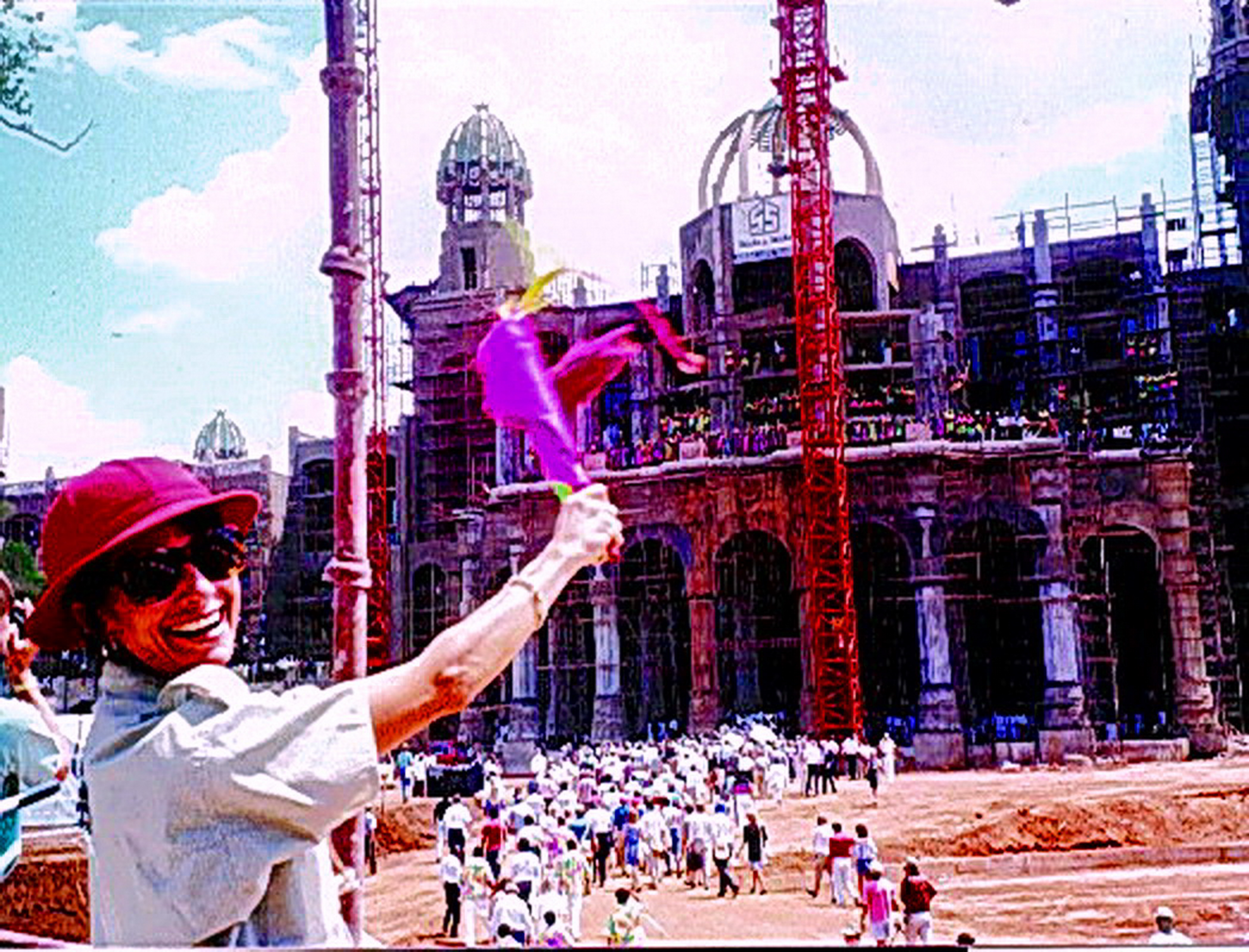

The spectacular show the pair mounted for the sod-turning and roof-wetting of the Palace of the Lost City at Sun City was a highlight of their careers. Dawn magicked a ‘mechanical ballet of synchronised movements starring the huge, bright yellow CAT machines’. This is a highly entertaining passage in the book. (Photo: Supplied)

Filming The Seagull’s Name was Nelson, one of the first ever South African music videos. (Photo: Supplied)

In the large rehearsal space in Johannesburg in preparation for their premiere of The Best Little Whorehouse in Texas, it was palpably obvious that a great deal was on the line. Des was producing the show, Dawn was directing it; the cast included Graham Clarke and Bill Flynn, Judy Page as Miss Mona, Victor Melleney as the sheriff and Abigail Kubeka as Pearl, the housekeeper. The ladies of the night included Bo Peterson, Anne Power, Adrienne Pearce and Jenny Cantan. I was a rookie arts writer flown in from Cape Town, where it was to be staged at the Three Arts. Des would later write of that Plumstead venue: “The booking system at the Three Arts was old-school and clumsy, with tickets tucked into a couple of thousand little cubbyholes in a dusty box office. It seemed to us that the seats were sold in random order with no bookkeeping that our production company could peruse or monitor with certainty. We were convinced that most houses were full or almost full, but when we were given each week’s tally, it always showed quarter or third houses sold. We queried this with the Quibells’ box office. ‘No, that’s all we sold last week; business is not good. We had to put in lots of paper (comps) every night.’” The Lindbergs’ solution: “Accordingly we sent Jon White-Spunner out front each performance just before curtain, to stand prominently in the front stalls and count every person sitting in the auditorium, with his finger doing an instant audit and noting it onto a clipboard.”

The Quibells saw it, and there was a sudden uptick in sales.

There are several tales about their penchant for bannings that pepper the book, such as their famous run of Godspell and the folk album that fell foul of the beak-nosed apartheid censors, but the one I will relate here applies to this risque musical. “It looked like this time we were on to a surefire winner,” writes Des. “Just one problem: one week before opening, guess what, the censors moved in and banned the title! We hastily changed all the adverts in the Press to ‘The Best Little ****house in Texas’ and briefed our lifelong friend, Adv Jules Browde, to appeal the banning of the word whore in the title… Jules presented eloquent and convincing arguments. The most telling was that to remove the word ‘whore’ from the title would cause confusion with the family TV series at the time on SABC called Little House on the Prairie. He cautioned with a straight face that parents could easily be tempted to bring 10-year-olds to see the show…

“The Appeal Board agreed to restore the word ‘whore’ in the title but ordered certain changes in the script. Miss Mona’s line ‘Best fuckin’ Eggs Benedict’ was duly amended to ‘Best friggin’ Eggs Benedict’. Further, we were required to alter the sentence ‘take the bull by the balls’ to ‘take the bull by the cojones’ on the justified assumption that the SA censors were not conversant with Spanish terms for male body parts. When we resumed the tour the new line of course got a much bigger laugh each night than the forbidden original.”

Without repeating the entire book, we’ll have to leave it on that ballsy note. There is just so much worth reading in it. The only pity is that Dawn did not stay with us to see it published. Let Des have the last word then:

“If this book achieves nothing else, I am determined that it will help me to sign off on our story in a way that does justice to the extraordinary leader, wife, mother, partner and lover Dawn was. I confess that the mere thought of performing without her by my side is, right now, unimaginable.”

Strength, sir. And respect. DM/ML

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

Beautifully written Tony. Thank you.

What a terrific review. What a duo…

16 Rietfonteins could certainly be the theme song of my life, aka The Eardstapper. I remember folk concerts in old church halls (we were too young for the Troubadour) with Des and Dawn, the Blundells, Jill Kirkland, our folks even took us to the Jeremy Taylor and “Minum” concerts, What a jol! So very subversive at the time. This land is your land, this land is my land.