FOSSIL EVIDENCE

Two-million-year-old bones reveal how our ancient ancestors got about

A new study shows that sediba was on the evolutionary trail towards the very human trait of bipedalism, but with a safeguard to protect against the predators that prowled the savannah.

Parts of the skeleton rarely seen in the fossil record have provided the missing link into explaining how one of our closest ancestors got about.

Those bones were two-million-year-old lumbar vertebrae that came from several specimens of Australopithecus sediba.

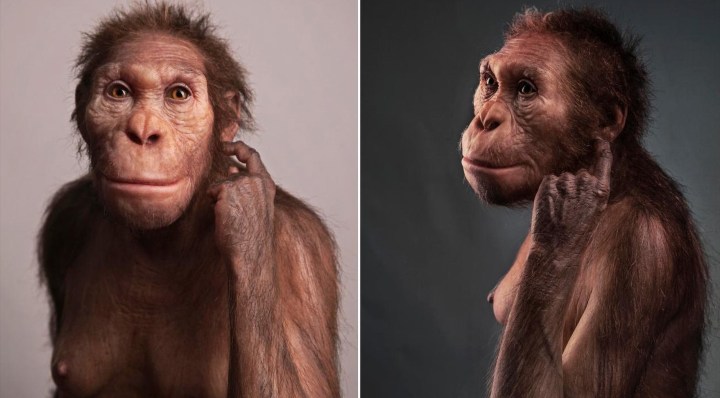

Life reconstruction of Australopithecus sediba commissioned by the University of Michigan Museum of Natural History. (© Sculpture: Elisabeth Daynes / Photo: S Entressangle)

What these bones revealed under a CT scan is that Au sediba not only spent time walking, just as humans do today, they were equally strong climbers.

The research was undertaken by an international team of scientists. Their findings were published on Tuesday in the open access journal e-Life.

What enabled them to conduct the study was the remarkable preservation of fossils that were found and recovered in the vicinity of Malapa in the Cradle of Humankind, near Johannesburg.

“If you look at the [fossil] record of associated vertebrae, it’s microscopic, and generally very, very badly preserved,” says Professor Lee Berger from the University of the Witwatersrand, who is an author on the paper and leader of the Malapa project.

“The lumbar region is critical to understanding the nature of bipedalism in our earliest ancestors, and to understanding how well-adapted they were to walking on two legs,” added Professor Scott Williams of New York University and Wits University and lead author on the paper.

The bones were scanned at Wits University using a CT micro scanner.

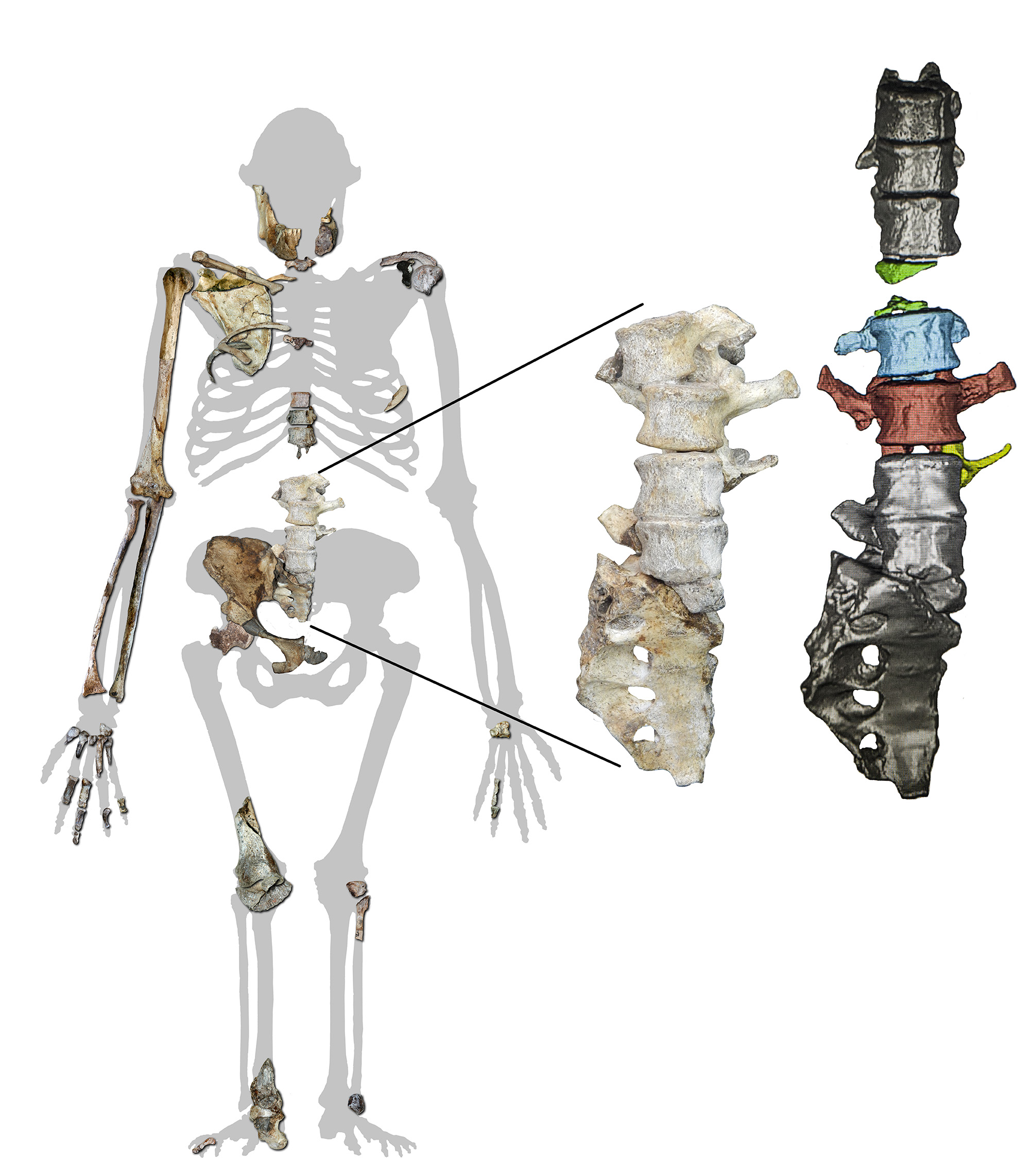

Australopithecus sediba silhouette showing the newly found vertebrae along with other skeletal remains from the species. The enlarged detail (a photograph of the fossils in articulation on the left; micro-computed tomography models on the right) shows the newly discovered fossils, in colour on the right between previously known elements in grey. (Image: NYU & Wits University)

Australopithecus sediba silhouette showing the newly found vertebrae (coloured) along with other skeletal remains from the species. (Image: NYU & Wits University)

“The lower part has the lordosis curvature of the spine, which is a clear indication that sediba was a terrestrial biped walking on two legs,” explains Berger. “Then halfway up, [the spine] changes completely in a way that you only see in climbing apes.

“We found the missing link between the upper body and lower body and it actually proves that they are absolutely doing both [walking and climbing] spectacularly well.”

Sediba is a relatively new addition to the human family tree. The first specimen was discovered at Malapa in 2008 by Berger and his then nine-year-old son Matthew. Since then other specimens have been found, including five that were part of the study and were excavated from a mining trackway that runs next to Malapa.

The hominin had a relatively human-like face, was powered by a 420cc brain and is believed to have eaten grasses, sedges, fruits and bark.

Sediba’s mosaic of human and apelike traits, which included long arms, curved fingers and a humanlike pelvis, had scientists suspecting that this hominin was spending time on the ground and in the trees.

“The spine ties this all together,” said Professor Cody Prang of Texas A&M, who studies how ancient hominins walked and climbed. “In what manner these combinations of traits persisted in our ancient ancestors, including potential adaptations to both walking on the ground on two legs and climbing trees effectively, is perhaps one of the major outstanding questions in human origins.”

The next phase in the research, says Berger, will be trying to work out what sediba was climbing. It may be that this early relative was clinging on to cliffs or living in sinkholes, similar to what baboons do today. Clues to this might be gleaned from the well-preserved skeletons that were found at Malapa.

What the study reveals is that sediba was on the evolutionary trail towards the very human trait of bipedalism, but with a safeguard to protect against predators, like false sabre-toothed cats, that prowled the savannah.

“Bipedalism was our lineage’s niche, that’s something we invented. And what we now understand from discoveries like this is that we sure kept a parachute on,” explains Berger.

“And that parachute was the ability to climb until we were darn sure walking worked.” DM

[hearken id=”daily-maverick/8835″]

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

Comments - Please login in order to comment.