HIGH AND DRY

No dam help: As a water disaster grips South Africa, the minister says there’s ‘no crisis’

The lack of water in many areas is a disaster, but the government seems to be burying its head in the sand, denying there is a crisis. Meanwhile, people are suffering.

Communities in Limpopo that have not had a drop of tap water for almost 20 years have been forced to draw water from the Olifants River. As a result, many young people have drowned, been attacked by crocodiles or become ill with water-borne diseases.

On 15 November, Johannesburg Water cut supply for at least 54 hours across large parts of the city as Rand Water, the entity’s main supplier, conducted planned maintenance. Some small towns in the Eastern Cape and KwaZulu-Natal have been dry in places for more than two years because of drought and failing infrastructure.

In the extremely drought-stricken metro of Nelson Mandela Bay, which is fast running out of water, businesses have started fixing leaks at schools because the government has failed to do so.

The increasing scale of water supply cuts and shortages across the country has led activist Awande Buthelezi to state: “We are looking at a disaster.” Buthelezi has run a project with the South African Food Sovereignty Campaign since the first level 4 lockdown in 2020, to which people can report when they are water stressed. Despite acknowledging that “overall South Africa has less water than it needs”, Minister of Water and Sanitation Senzo Mchunu downplayed the disaster by saying “this does not mean that we are in a crisis”.

Mchunu admitted that municipalities countrywide had let them down, but he said his department was not about to “get under the bus” with them and would take over their water services if they did not perform.

A Westbury resident fills his neighbour’s buckets from a tanker during a water outage. (Photo: Julia Evans)

Within days of Mchunu’s statement, the people of Elandskraal, Morarela, Mbuzini, Regae (Tsantsabela) and Dichoeung villages in the Sekhukhune District Municipality in Limpopo protested in front of the Union Buildings. Their water was shut off in 2003.

Buthelezi said that while it seemed that South Africa was caught up in an escalating series of crises, there might be a feeling that we “can’t just add another crisis”.

“We all agree that we are having an electricity crisis. We are not in a rush to add another. But this one, this one is equal if not superseding all our other crises,” he said.

There are 95 communities that have had or are experiencing extreme water stress. In almost all of them the accounts by residents start with the words: “My children must fetch water from the same stream where the cattle drink.”

Mchunu said: “South Africa is a water-scarce country. Overall South Africa has less water than it needs… but that does not mean that we are in a crisis.

“If we manage the water that we have, the water that is available at the moment, we will manage everywhere in the country. We will go on well; in other words, meeting the constitutional obligation that water is a right but also meeting our mantra that water is life,” he said.

“But it requires management… we need citizens of the country to join.”

Buthelezi said they started the project for communities to report water stress when former water and sanitation minister Lindiwe Sisulu promised that all communities would get emergency relief water during lockdown.

“The Eastern Cape and Limpopo were hardest hit. For them Day Zero is nothing new. They were living it for years.

Westbury residents help one other collect water reserves from a water tanker during a water outage. (Photo: Julia Evans)

“I think the right to dignity really gets to the heart of it,” he said. “The situation is being used to disempower certain members of the community. Those who have access to water are making people pay exorbitant fees for access. Tanks are being controlled by people who decide who gets and doesn’t get water,” he said. “It is not right. It is a disaster.

“I do think the water is a big, big crisis. You can see how spread out this is – there are definitely more places that we have not yet touched on,” Buthelezi said.

He added that the Department of Water and Sanitation was open to questions from communities.

“But they told us the problem is at the municipal level. They said we must meet with municipalities.”

The municipalities point out that they are also battling with a seemingly unprecedented spate of vandalism. Bulelwa Ganyaza from the Chris Hani District Municipality in the Eastern Cape said a water outage lasting for days was caused in Middelburg in the Karoo, when the persistent vandalism of water infrastructure severely affected water service provision, especially in areas with existing shortages.

“Extensive damage has been caused to a water pipe from Matjieskloof borehole in Middelburg, adding more strain to [an] existing water shortage in the area. The municipality strongly condemns such an act as it deliberately sabotages provision of the service.”

Mkwinti Mduduzi fills containers at Dawid Stuurman Airport. Water tankers were sent to Walmer in Gqeberha after the supply was cut to repair a leak. (Photo: Deon Ferreira)

In other places such as Somerset East, which has been battling water outages for the past month, residents were simply met by a stony silence from the municipality.

Gift of the Givers’ Dr Imtiaz Sooliman said his organisation had multiple emergency response projects on the go to help water-stressed communities. “The situation is a real challenge, especially in the Eastern Cape.

“We are busy on so many fronts in that province. The government urgently needs to start drilling in Gqeberha to reduce the effects when the city hits Day Zero.

“In Gauteng, we increased water delivery capacity at Rahima Moosa Hospital. The hospital is fully dependent on our borehole. At Helen Joseph Hospital we installed a filtration plant and here too increased the capacity for water delivery to the hospital.

“In Makhanda we [have] just installed a new filtration system at Ntsika School to improve the quality of the water. The 34,000-litre Coke water tanker made available to Gift of the Givers is now going to play a huge role in alleviating water challenges in that town.

“We’ve done maintenance and repair on all our boreholes in Adelaide, Bedford, Graaff-Reinet and Klipplaat to improve water delivery in these areas. We currently have drilled or are busy drilling new boreholes in Jansenville, Fort Beaufort, SS Gida, Cala, Hewu and Butterworth hospitals. Sterkspruit Hospital will follow soon. We’ve finally fitted all the connections to allow water flow at three schools in Gqeberha where we drilled for water,” he said.

Mchunu said his team would go to Pietermaritzburg in December as it also needed urgent augmentation of water sources to prevent Day Zero – which will also affect Ugu.

“They will run out of water very soon unless we do something,” he said. “We have plans.”

He said there was no need for protests because his department was making plans.

Limpopo resident Oupa Tshoshi and his fellow townsmen, who have had unreliable access to water since 2003, outside the Union Buildings in Pretoria. (Photo: Julia Evans)

“In the Free State municipality of Maluti-a-Phofung… we went there to plan what to do about the water. We want to give them water. It is not a problem of not having a source. The municipality was not able to reticulate water to citizens. We went there to say: you choose. Tell us the truth. Can you reticulate water, or do you need our intervention? Since our discussion, 20% of work has been done.”

They would go to Giyani in Limpopo next. “We are going there to make sure that the pipe gets completed once and for all. We don’t want a presentation of slides and so on. We want to touch the work that they have done and talk about money.”

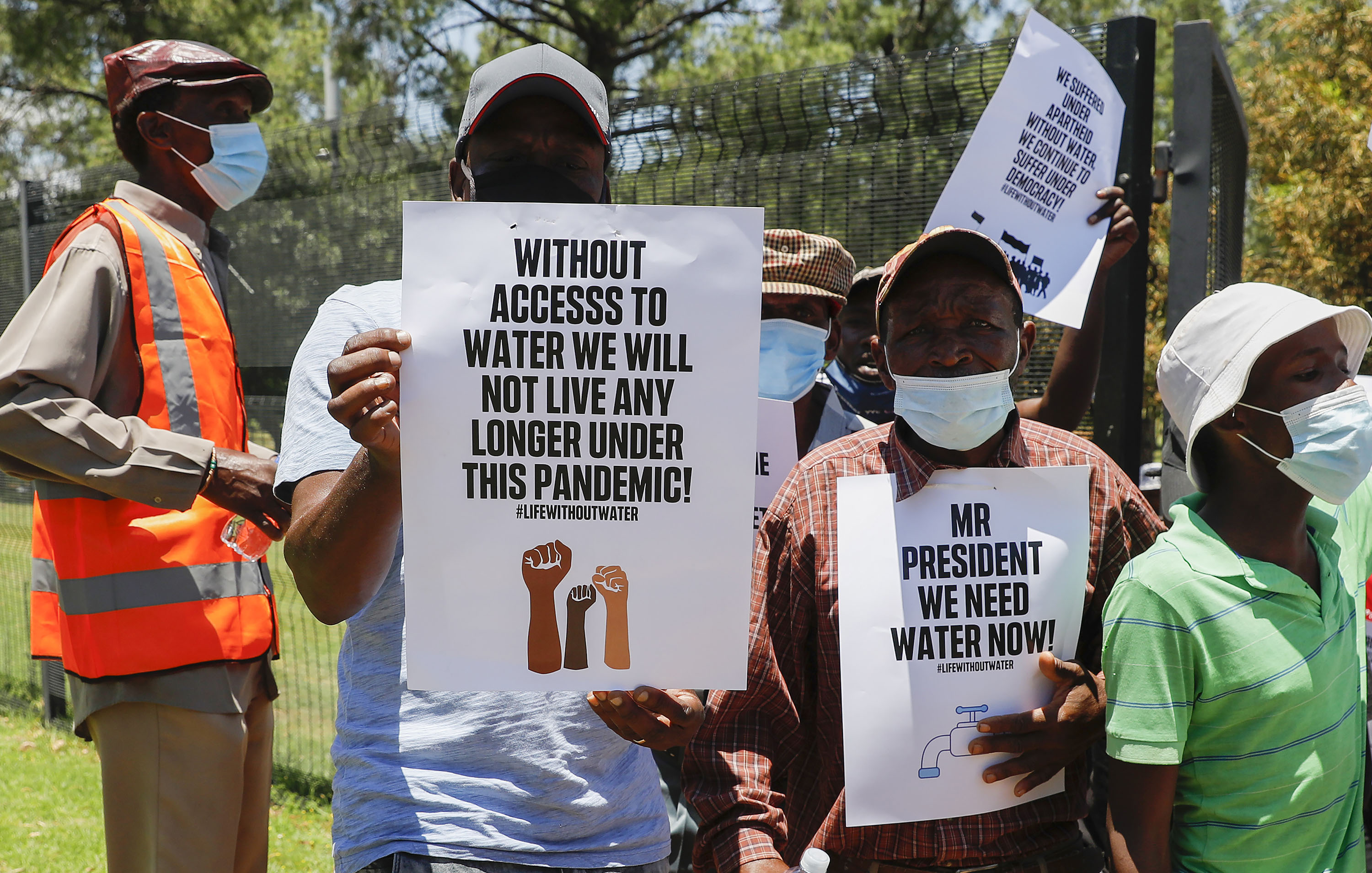

Frustrated communities from Limpopo this week staged a protest in front of the Union Buildings because they have been struggling to access water since 2003.

Butibuti Mabuso (55), who has lived in Limpopo all his life, said he had been without water for a long time.

“We used to have water before. Before this issue of local government came to be, we had water, pure water coming from the taps. But the situation changed in 2003 when they said they were upgrading the plant, then they stopped our plant and then they said they are doing a new plant and then they said they will give us water. But since 2003 we have never had water.”

Water would be delivered only every one to two months, he said. They took the district municipality to court in 2016, which ruled in their favour. The municipality promised to deliver.

Struggling to survive, residents are taking water straight from the Olifants River.

“It’s not safe, but what can we do?”

Since 2005, many young people have died in the river – from drowning or being attacked by crocodiles. People also get sick with diarrhoea and skin rashes. “It is very difficult. There is nothing that you can do. You can’t even think about some of the things.”

The communities have delivered memorandums to various ministers and presidents, but they are ignored.

Moreki Seroka (45) said that having no water made life very difficult. “Sometimes you can’t cook. You can’t wash your clothes. It has been a long, long time of us complaining. Our hope today is that maybe the Office of the President will do something. The water tankers come once or twice a week. The water lasts a day, sometimes not even a day. When the water truck arrives, people run to the tank. They even sometimes hurt each other because they fight for the water because it’s rare and there are many.”

Residents of Tsantsabela township near Marble Hall in Limpopo protest at the Union Buildings in Pretoria over water supply and interruptions on 18 November 2021. (Photo: Phill Magakoe)

Dr Gisela Kaiser, the engineer seconded by Treasury to help deal with the crisis in Nelson Mandela Bay, said the region’s “window” for heavy rain was closing soon without significant falls having been recorded in the catchment area.

“I am obsessively watching the weather sites,” she said. “But every time we see a predicted extreme weather event for the region the intensity decreases as time passes.”

After November, the chances of significant rainfall in the area become much less likely until May 2022. This is the goal, she said. “We must make the water last until then.”

As dam levels drop close to empty, the Department of Water and Sanitation has limited extraction from one of the major supply dams.

The Nooitgedacht scheme pipes water from the Orange River to the metro but cannot run at full capacity as payment failures by the Amatola Water Board have delayed the completion of the third phase of the project.

Kaiser said that, for the future, the city’s best bet was to ring-fence water rates and use them to renew and develop infrastructure.

“All the metros should do this.”

While some rain has fallen in the area in the past few weeks, she said it merely bought a few extra days until Day Zero.

The CEO of the Nelson Mandela Bay Business Chamber, Denise van Huyssteen, said the metro had reached a tipping point.

“It is becoming increasingly difficult to retain investment in this metro, due to the dysfunctionality of the operating environment. While the water crisis is a very serious issue, businesses face a perfect storm of challenges such as the unreliability of electricity supply; cable theft, which is causing prolonged disruptions to electricity supply; crumbling water and electricity infrastructure; badly damaged roads; lack of cleanliness of the city, and so on.

“A lot of these issues are the outcome of years of political instability and poor running of the metro. It is absolutely vital that whichever coalition government ends up taking control over the metro, that they focus on putting the best interests of the city and its people first.

“We have reached a tipping point and if critical issues such as clean governance and service delivery are not addressed, Nelson Mandela Bay is at a high risk of losing investment and much-needed jobs,” she said.

So far, through the chamber’s Adopt-a-School initiative, 16 water tanks have been donated to schools and a clinic with a special focus on the Kwanobuhle community, which would run out of water first. She said businesses had adopted 35 schools that had been identified as high water consumers due to faulty or damaged plumbing systems.

In Centane in the Eastern Cape, villagers who last had water in 2017 are turning to the court to force the municipality to provide them with water. But they have run into a wall of government not responding to court orders, with the exception of the Amatola District Municipality, which filed a plan but is currently under administration and is struggling financially.

“We are seriously disappointed and disheartened by the government ignoring the court order to tell us when and how they intend to provide us with water. Their actions point to an uncaring government and one that is willing to let their most vulnerable people suffer during a global pandemic. We need water and we need the government to commit to when and how they will give it to us. It’s that simple,” said Gustaf Wayile, a community activist from the village of Nombanjana in Centane.

“These delay tactics by the government spell very bad challenges for our lives. We are desperate for water and have been for at least the past five years. Many of us suffer from chronic diseases that require us to take medication daily. This is a big struggle because we can never find the water to take our medication with. We are not asking for a lot; we just want to be afforded our dignity through our basic rights,” said Novoti Mshenxisi from Ngcizela in Centane.

In Johannesburg, with widespread outages because of maintenance work, residents struggle to access water.

In Forest Hill, in Johannesburg South, the taps ran dry on 15 November, and no water tankers have arrived.

Mike Moyo, who works at a mechanic shop, said he filled his buckets before the outage, but after a few days his reserve water became dirty and undrinkable.

Moyo also bought bottled water. “There are some people who didn’t know that the water is going to go off, so you see them with buckets trying to borrow from family members or friends.”

Anna Mkhize (47) from Forest Hill said the lack of water affected her taking her daily medication, which is vital for her health.

“I’m using medication, I can’t drink it because there’s no water. I didn’t know that the water was going to [be switched off],” Mkhize said.

“It is very hard. It’s better that there’s no electricity than no water.”

Villagers from Centane in the Eastern Cape protest over a critical lack of water. (Photo: Supplied)

She added: “I don’t have the water. I don’t know which place I can go to get the water. I can’t even get the water to cook, just to eat. My stomach is empty because there’s no water.”

She isn’t alone. Mkhize said many people in her community could not afford bottled water.

In the heat of summer, more than 30°C, the people of Forest Hill were battling with what authorities described as a “necessary inconvenience”.

“If there’s no water, we can’t survive,” Mkhize said. “As you see, we [have] got no money, there’s no jobs, there’s nothing. But we keep on voting.

“We are suffering very badly. We suffer for food, suffer for water, we suffer for electricity.

“There’s nothing that is alright. There’s nothing at all.”

Mchunu’s spokesperson, Kamogelo Mogotsi, was asked if he would like to revise or elaborate on his statement that there was no water crisis in the country. She did not respond to questions. DM168

This story first appeared in our weekly Daily Maverick 168 newspaper which is available for R25 at Pick n Pay, Exclusive Books and airport bookstores. For your nearest stockist, please click here.

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

“Within days of Mchunu’s statement, the people of Elandskraal, Morarela, Mbuzini, Regae (Tsantsabela) and Dichoeung villages in the Sekhukhune District Municipality in Limpopo protested in front of the Union Buildings. Their water was shut off in 2003.” – Who did they vote for in 2005, 2009, 2013, 2017, 2021?

As the ANC crumbles, long overdue, the so-called Ramaphosa’s ministers still cry “No Foul”. But the chicken is coming to roost.

“Meanwhile, people are suffering.”

Wow, if ever a leading understatement that can be applied to everything the ANC touches.