DOSSIER: BATTLEGROUND ANTARCTICA

Explained: Russia’s 500 billion-barrel bombshell in Earth’s last unmined frontier

At the end of October, Daily Maverick revealed the exclusive findings in Part One of our international investigation into Russia’s years-long oil and gas surveys via the port of Cape Town. We not only reported Russia’s extraordinary claims that the Southern Ocean holds 500 billion barrels in oil and gas. For the first time since Antarctica’s mining ban entered into force in 1998, we showed that the Russian state explorer has never stopped combing the world’s greatest deep freeze for its suggested mineral wealth. For a summary of key findings, we publish the shorter explainer edition here.

A mammoth potential of 500 billion barrels in hydrocarbon “resources” — the building blocks for oil and gas — might be buried in supergiant oil fields beneath the Southern Ocean, the warming, climate-threatened waters that wrap around Antarctica.

This extraordinary declaration was made by Rosgeo — the Russian Federation’s largest geological exploration holding company — while its polar research vessel was stationed in the port of Cape Town.

First adopted in 1991, the Antarctic Treaty’s widely praised 1998 mining ban outlaws “any activity relating to mineral resources, other than scientific research”, in the sweeping white wilderness below 60°S.

However, in Part One of this investigation, we laid bare Russia’s vast oil and gas nexus under the treaty via Cape Town since 1998. Our revelations also follow in the wake of the celebrated new “Paris Declaration”, a climate manifesto issued in June by 54 treaty nations to “implement actions consistent” with the global Paris climate agreement.

Yet, it is also this treaty that oversees a ban that may be changed from 2048; and this same treaty is used to justify research into the very fossil fuels threatening to derail an irreplaceable wildlife refuge, and raise global sea levels. These are virtually unreported realities that can be seen playing out in the 500 billion-barrel bombshell statement issued from Cape Town harbour — just as a pandemic for the ages stunned the world and swamped global headlines in February 2020.

Claims compare to the world’s highest proved oil reserves

Issued with a headline leaving little doubt about the nature of Rosgeo’s Southern Ocean missions, the exploration company declared that it had “completed explorations of the geological structure and oil and gas potential of the Antarctic shelf”.

These “explorations” were spearheaded by Rosgeo’s contracted subsidiary, the Polar Marine Geosurvey Expedition (PMGE) — a privatised joint stock company that prides itself on “explorations for minerals in all the most hard-to-reach regions of the Earth”.

If recoverable, those 500 billion barrels — or 70 billion tons in “hydrocarbon resources” — would be a climate-busting quantity of fossil fuels simmering beneath a threatened region performing global nature services.

They would also exceed the world’s highest proved reserves for any single country, which belong to Venezuela at 300 billion barrels.

‘Prospects’ of Earth’s last unmined frontier

Southern Ocean seismic cruises have habitually drawn seabed “cores” that bring confidence to, for instance, the UN’s IPCC climate findings. Future cruises might even assess possibly dangerous losses of methane gas deposits as the ice warms and retreats.

The same mapping equipment, however, can also be directed to betray potentially lucrative oil and gas reserves for possible extraction.

It appears that this is exactly what has been done by the Akademik Alexander Karpinsky, an ageing polar research vessel that Rosgeo’s subsidiary has used annually to sail to the Southern Ocean via Cape Town, an official Antarctic aerial and shipping gateway.

The Karpinsky in Table Bay harbour, August 2020. (Photo: © Tiara Walters)

The 37-year-old vessel hosts, among others, seismic equipment such as an airgun array and a 640-channel, 8km streamer with hydrophones, which can stitch together maps of oil and gas potential by bouncing sonic explosions off the seabed.

“Based on the results of the work carried out,” a PMGE online geophysics report reveals of the Karpinsky’s Southern Ocean missions, “conclusions can be drawn about the prospects of a particular region of the continental margin of Antarctica for minerals”.

Time bomb ticks as marine parks run aground (again)

It is not entirely clear how the Madrid Protocol, the treaty’s environmental chapter that governs the ban, views commercial prospecting, but in on- and off-record interviews for this investigative series veteran Antarctic academics told us that prospecting activities would, at the very least, defy the spirit of the ban — and most likely be in breach of it.

Indeed, an abandoned 1988 Antarctic mining pact defines “prospecting” as “identifying areas of mineral resource potential for possible exploration and development”.

And it is into the so-called “Riiser-Larsen Sea” off East Antarctica that the Karpinsky’s 2020 “marine explorations” carried her crews on a quest that looks and smells just like the prospecting missions defined by the abandoned mining pact.

Over two months in early 2020, PMGE conducted nearly 4,500km in oil and gas assessments in the Russian-named Riiser-Larsen Sea. In 2019, the Rosgeo subsidiary zeroed in on the Pacific wedge that pushes up against the West Antarctic ice sheet, the continent’s fastest-melting section.

Here, the polar vessel trained her crosshairs on the Amundsen Sea as well as the Ross Sea — since 2016 the world’s largest marine protected area (MPA) at 1.5 million square kilometres.

Since then, talks on long-awaited MPAs that would protect vulnerable marine habitats have repeatedly failed, because treaty nations tasked with proclaiming them seem unable to agree.

Invoking “scientific reasons” and even suggesting that protection efforts may be a Western territorial cabal, Russia, for instance, has repeatedly objected to the MPAs, while China has also been flagged.

At the end of October, MPA talks struck the icebergs of impotence a fifth year in a row.

Unpacking Antarctica’s ‘raw material potential’

The Rosgeo communiqué may create the impression that 2020 and 2019 marked the very first years since the Nineties that Rosgeo assessed the Southern Ocean’s oil and gas reserves — as reported by some market media.

Reviewed by us in original Russian form, our dossier of evidence shows otherwise, exposing how the Karpinsky’s oil and gas surveys have unfolded year by year after the 1998 ban formally entered into force in Madrid.

Between 2021 and 2006, the Karpinsky’s expedition diaries — compiled under state contracts — appear replete with exhaustive, commercially weighted descriptions of Antarctica’s suggested mineral riches.

These diaries size up resources as, for instance, the “assessment of the mineral and raw material potential of the subsoil of Antarctica and its marginal seas”, while PMGE’s 55th anniversary report puts the identification of “large sedimentary basins”, apparently “promising for oil and gas”, right at the top of the subsidiary’s achievement pile.

The Ahlmannryggen range in the Norwegian-claimed territory of Queen Maud Land, East Antarctica. (Photo: © Tiara Walters)

A more detailed list of potential prospecting activities — both at sea and via aerial geophysical surveys over continental Antarctica — can be viewed in Part One.

To greenlight the hydrocarbon surveys, an environmental impact assessment (EIA) submitted to the treaty by the Russian Antarctic Expedition — the state arm that executes Russia’s Far South activities — emphasises the port of Cape Town as a strategic but legal transit node stretching as far back as 2001.

The same EIA outlines as a top objective the “preliminary assessment of the oil-gas bearing perspectives of the Cosmonauts Sea”, as well as planned work in other East Antarctic seas, which have since delivered a vast body of hydrocarbon data from substantial sedimentary basins, more than seven kilometres thick in parts.

‘The Rosgeo statement is a fake’

Not all scientific results from the Karpinsky’s expeditions, which we listed in Part One, betray an interest in oil, gas or minerals, but other papers by PMGE et al — published through the high-impact Nature Springer academic group — are hardly as subtle.

Among hydrocarbon-related findings released by Russian scientists since the 1998 ban, such papers include a 2020 Russian research effort in Geochemistry International, which tries to tease apart the “hydrocarbon generation” beneath Antarctic waters.

Replying to our request for clarification of Russia’s Antarctic activities, senior state geoscientist German Leitchenkov told us that Russia had previously communicated its position on this issue, which we outlined fully in Part One.

Leitchenkov is a polar geology professor at St Petersburg State University who, in fact, has collaborated with the Rosgeo subsidiary and studied Antarctica’s mineral potential.

“I think that the statement of officials from ‘Rosgeologia’ is a fake”, he told us, “due to their very low competence in fundamental Antarctic research.”

The ‘freedom of scientific investigation’ jamboree

Amid tensions over the true difference between scientific research and prospecting, polar law expert Donald Rothwell told us that the mining ban does not “prohibit research activity into oil and gas”.

A professor at the Australian National University, Rothwell advises that the “Madrid Protocol has to be read against the Antarctic Treaty’s ‘freedom of scientific investigation’ principle”. Together with peace, science is, indeed, a founding principle of the 1959 agreement that reserves the entire Antarctic for research and cooperation.

According to Alan Hemmings, an Antarctic governance professor at Canterbury University, commercial prospecting would be in material breach of the ban.

Hemmings was also commander of the British Antarctic Survey Station during the 1982 Falklands War. Like Rothwell, he points out that the treaty makes broad accommodations for scientific research — but there are “a number of globally used criteria for setting breaking points” between science and prospecting. Hemmings has also chronicled “clear” examples of Russia “asserting minerals and prospecting interests in the Antarctic since 2001”, published in more detail in Part One.

In response to our request for comment, Rosgeo told us that it was “in no way engaged in the exploration and exploitation of Antarctic mineral resources” — or any activity “going beyond the standard boundaries of non-commercial geology”.

Despite these firm denials, the 500 billion-barrel figure — or 70 billion tons — also appears in other official and state Russian documents, including Rossiyskaya Gazeta, the official government gazette. We report on those Russian-language documents here.

Ice to see you, Karpinsky

On 4 February 2021, almost a year after Rosgeo’s dramatic 2020 announcement, the Karpinsky nosed into the Southern Ocean via Cape Town yet again.

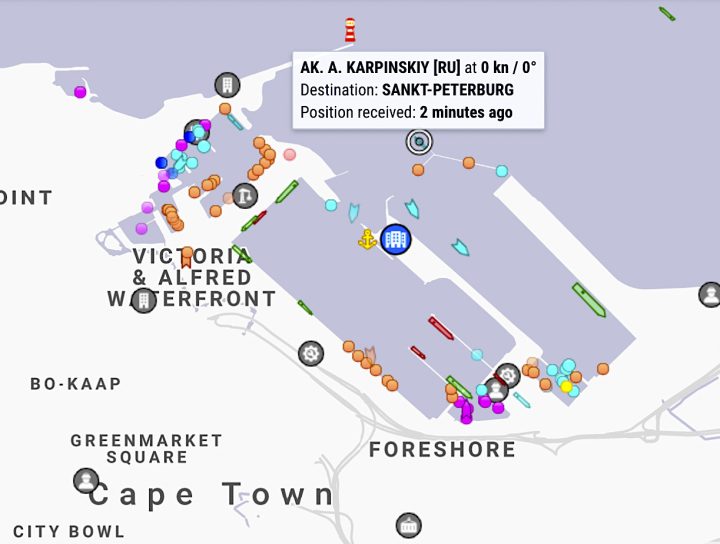

She returned to Cape Town from that mission on April Fool’s Day, where she spent several weeks tethered to the most inaccessible point of the farthest pier at Table Bay harbour, finally setting sail for her native port in St Petersburg on 26 June 2021, according to Marinetraffic.com data.

The Karpinsky in Table Bay harbour, June 2021, shortly before departure. (Photo: © Marinetraffic.com)

Russia’s hydrocarbon and mineral surveys may well push ahead in the 2021/2022 summer season and beyond, suggests an announcement by the Arctic and Antarctic Research Institute (AARI), which manages diverse science activities under the Russian Antarctic Expedition.

“I am glad that we have resumed the scientific programme of the seasonal expedition,” said AARI director Alexander Makarov, who did not respond to a request for comment on the nature of certain Russian scientific disciplines in Antarctica.

The Antarctic Treaty’s Committee for Environmental Protection also did not respond, while the Antarctic Treaty Secretariat declined to respond. The Scientific Committee on Antarctic Research, an independent but influential treaty advisory body, also declined a response.

“The past year was, due to the pandemic, in many respects, difficult,” Makarov continued.

“We have a lot of restrictions, a lot of ‘ifs’. But the main thing is that the season will be.” DM/OBP

For the complete story, references and supporting documents based on original Russian-language sources, read Part One in the “Battleground Antarctica” investigative series.

REPUBLISHING THIS ARTICLE: This or any of the articles in the “Battleground Antarctica” series may be republished, online or in print, under a Creative Commons licence. Each article must be republished in full and unedited. Where any of these articles are republished online, a hyperlink must be provided to the original piece on the Daily Maverick website.

[hearken id=”daily-maverick/8835″]

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

Comments - Please login in order to comment.