POLITICAL REFLECTION

The complex legacy of FW de Klerk, the South African president who straddled apartheid and democracy

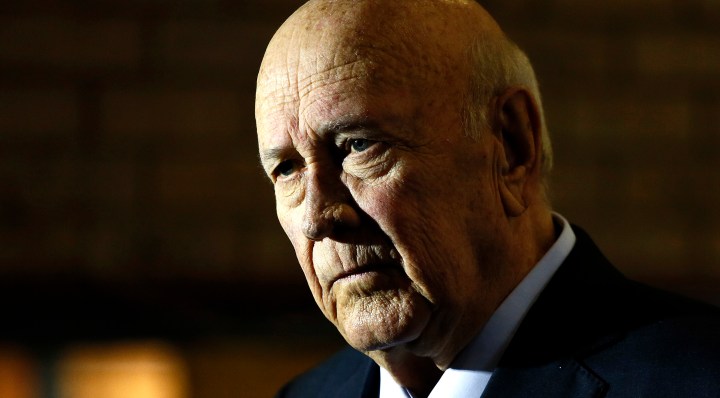

A complex man who left a complicated legacy, FW de Klerk died on Thursday morning at the age of 85 after a lifetime of South African political life that straddled both the apartheid world and the new democratic order.

No South African can be neutral about FW de Klerk’s place in their country’s history. To some, he was the president who took the decisive steps to break with the ideology and policies of apartheid to help lead South Africa away from the Coventry it was locked into because of those harsh policies.

To others, he was the man who foot-dragged his way forward, even as the brutalities continued during his tenure in office, right up until the establishment of the country’s government of national unity under Nelson Mandela.

For yet others, he was the man who turned his back on “his people” to embrace those liberation movements and thereby “sell out” the nation.

For still others, he was an ordinary man driven to negotiate with his enemies, despite his deep reluctance to do so, because the circumstances of the country forced him to do so.

And to yet other observers, FW de Klerk was a man who had studied and contemplated history and was able to look at developments in Mikhail Gorbachev’s Soviet Union to conclude the way forward necessarily demanded a new and different path. Perhaps he was all of these, simultaneously.

I first encountered the name of Frederik Willem de Klerk back in early 1976. At that time, I was a junior officer at the US Consulate General in Johannesburg. One task was to be a member of the committee that selected individuals invited to visit the US as our country’s guest for a month in a low-key trip to explore their own professional and personal interests. There was a limited number of such grants and, inevitably, the various sections of the embassy, through their representatives, always wanted to ensure their choices were selected for these trips.

From Johannesburg, we had a long list of people for whom we hoped to obtain these visits – ranging from members of the Progressive Party to individuals deeply involved in the kinds of organisations that would eventually coalesce into the United Democratic Front. We naturally hoped we could obtain committee agreement to endorse all of them. The embassy’s political section, the office that kept abreast of government developments, had one or two nominees as well, and one of them, in particular, had caught my eye.

That nominee was a young member of the country’s all-white Parliament, recently elected, and representing the district around Vereeniging. A look at his biographical information with the nomination form told the tale of a man who was virtually a “prince of the royal blood” within the National Party. His father was a member of the first National Party Cabinet that took over in 1948, and one of his uncles had been a prime minister of South Africa early on.

Born in Johannesburg, he had studied law at the Potchefstroom University for Christian Higher Education, and his religious affiliation was the “Dopper” wing of the Dutch Reformed Church; a sect so strict, so deeply fundamentalist, they didn’t even allow their members to dance (although they could drink).

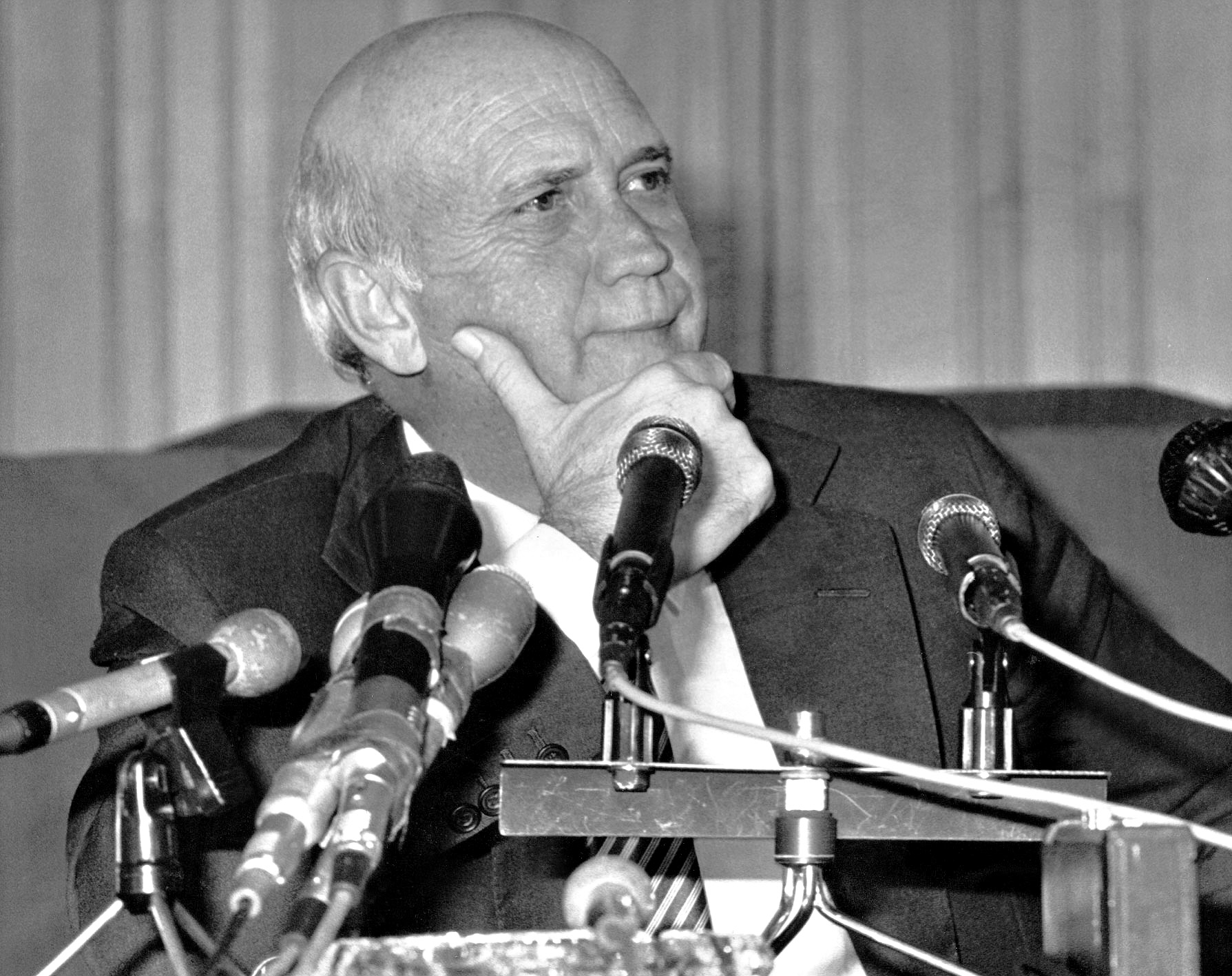

29 February 1992. South African president FW de Klerk at a press conference with his hand on his chin. (Photo: Gallo Images)

My reaction to his nomination was almost visceral: What conceivable purpose would be served in wasting one of our small handful of grants on somebody so retrograde (and here I may even have used the word “Neanderthal” to describe his political beliefs) that there was no point to be served by doing so? What kind of future would this nominee help build in South Africa? After some horse trading, several of our nominees were accepted – as was the young FW de Klerk MP.

Years later, De Klerk outmanoeuvred one-time party favourite Chris Heunis to become party leader and then successor to State President PW Botha, who had been laid low by a serious stroke. At the time, De Klerk was minister for national (read: white) education, a relatively unlikely perch from which to become the head of a government then facing its most difficult moments. While he was not a direct part of the national security machinery, he did sit on Cabinet committees which oversaw much of what the national security part of government was doing.

Shortly after what might be interpreted as a peaceful, intra-party coup, vaulting over more senior party figures, De Klerk was the subject of an extensive profile in the New York Times Magazine, published in November 1989. It is worth quoting at some length for its insights into the mind of the man as he was in the midst of taking the measure of his nation, almost as if he were perched on the edge of a caldera, peering into an active, smoking volcano, realising something must be done.

Christopher Wren’s article noted, “As de Klerk tells it, a 1976 visit to the United States as a guest of the United States Information Agency convinced him that race relations could not be left to run their course. He enjoyed New York, Washington, San Francisco and Los Angeles. He marvelled at the Grand Canyon and listened to late-night jazz in New Orleans. But, he says, ‘I saw more racial incidents in one month there than I previously, at that stage, had seen in South Africa in a year. I was involved in an incident where the bus driver called a black American “boy,” and a fight immediately erupted.’ On one taxicab ride, he says, the driver shouted epithets at black pedestrians, and de Klerk scrunched down in the rear seat out of embarrassment.

“The lesson of his American sojourn, he decided, was that ‘the negative effects of racism isn’t limited to South Africa and that it was a problem in the hearts and minds of people; also, that in a country with a great conflict potential, with a much more complicated population structure’ – and here he meant South Africa – ‘that it is necessary to manage the conflict potential which arises from a multiracial society, as we believe, in a non-discriminatory manner.’ This conviction that race relations must be deliberately controlled colors de Klerk’s philosophy of change.”

Shortly after this article was published, I found myself attending the annual gathering of the nation’s political scientists’ association. By late 1989, after years of intensifying violence, political action and governmental reactions and repressions, along with increasingly strident international condemnation, right in the middle of the convention’s dinner where there the keynote speech was about to be delivered by a well-known US political scientist, one of the convention’s organisers came rushing into the meeting, grabbed the microphone, and announced De Klerk’s government had just released a number of leading (and near-legendary) figures including Govan Mbeki and Walter Sisulu from their incarcerations, and without further preconditions. (It was generally unknown at the time that there had already been a series of meetings between the government and the ANC.)

By 1993, De Klerk and Mandela had shared the Nobel Peace Prize for their roles in the country’s evolution, even as the two men at that time barely had a veneer of cordiality left in their increasingly fraught relationship. Still, in the aftermath of the first all-race election and the establishment of a provisional Constitution, De Klerk accepted Mandela’s offer to become the country’s second deputy president.

Even so, when De Klerk made his speech the next year in Parliament on 2 February, announcing his intention to release Mandela as soon as arrangements could be concluded, it did not yet seem entirely real that a crucial moment in South Africa’s history was actually upon the country. But looking back at what De Klerk had told the Times’ correspondent in 1989 about the necessity of careful processes and orderliness in managing change, one could see his ideas working themselves out in his actions.

5 May 1990. South Africa. Constitutional Negotiations. ANC president Nelson Mandela gives an international press conference with State President FW de Klerk. (Photo: Gallo Images)

By 1991, while that first, often-acrimonious Congress for a Democratic South Africa (Codesa) meeting was taking place, my family and I had accepted an invitation to visit the trout farm of acquaintances up in the Mpumalanga highlands. That weekend it rained for most of the time there, save for the occasional break when an outdoors walk was possible, and so we, and the other guests, all huddled around the television to watch the Codesa proceedings. There was that moment when De Klerk and Mandela truly got into it, complete with shouting and finger pointing. Horrified, some of those in our gathering waited to learn if actual hostilities were about to break out, even as it became clearer and clearer the road for South Africa’s transition to a more democratic society was going to be an exceptionally bumpy, sometimes very angry one.

In its summing up of De Klerk’s life, The Washington Post noted, “There were times when the two sides engaged in bitter recriminations, with each accusing the other of bad faith. Mandela denounced Mr. de Klerk as ‘the head of an illegitimate, discredited minority regime.’ Mr. de Klerk argued that he faced the difficult balancing act of placating hard-liners inside his cabinet and ruling party, while making adequate compromises to keep Mandela and the activists at the table.”

And it was true that at that time the De Klerk government was still officially in charge of the country, and some argue forcefully that the deaths of activists and marchers in various outbreaks of fighting or in multiple killings at more peaceful gatherings in that period must also be for De Klerk’s account, even as he gained applause for propelling the national transition forward.

By 1993, De Klerk and Mandela had shared the Nobel Peace Prize for their roles in the country’s evolution, even as the two men at that time barely had a veneer of cordiality left in their increasingly fraught relationship. Still, in the aftermath of the first all-race election and the establishment of a provisional Constitution, De Klerk accepted Mandela’s offer to become the country’s second deputy president.

The transfer of power and De Klerk’s acquiescence in the new arrangements led some among his fellow Afrikaners to see him as a virtual traitor to his group, perhaps something like how many rich, conservative Americans had viewed President Franklin Roosevelt as a traitor to his class in proposing and pushing for the New Deal and its reform measures during the Great Depression.

Still, years after the transition had taken place, in a lecture at Rand Afrikaans University (now part of the University of Johannesburg), De Klerk explained what he had insisted had driven him and his Cabinet to break out of the no-win situation they had inherited. At that lecture, he argued it had been a realisation that if things remained as they were, his people, in such a future, would never be able to offer their children and grandchildren the kind of life they themselves had been able to enjoy when they were growing up. Therefore the decision was inevitable.

Before he became state president, De Klerk had been minister of national education from 1981-89 and in response to a question I had sent him several years ago in connection with another project, he had written back that he had always had sufficient respect for freedom of expression, saying, “At all times when censorship fell under me I adopted an approach of minimum interference in the freedom of writers, artists and the like.” And perhaps that really was true, and of a piece with the way he viewed his role in South Africa’s transformation.

In viewing his life in totality, in his rise through the Afrikaner elite and National Party government, to his gradual realisation that change in South Africa’s political arrangements was a necessity, his trajectory demonstrates a degree of practicality and pragmatism unusual in many politicians. Ideological principles mattered, until they no longer did, and then he changed.

Or as the late journalist and historian Allister Sparks had judged him in Tomorrow is Another Country, “The new president, short, rotund, balding, polished but without much charisma, head cocked to one side like a sparrow and bobbing on his right foot as he spoke, turned three centuries of his country’s history on its head. He didn’t just change the country, he transmuted it.”

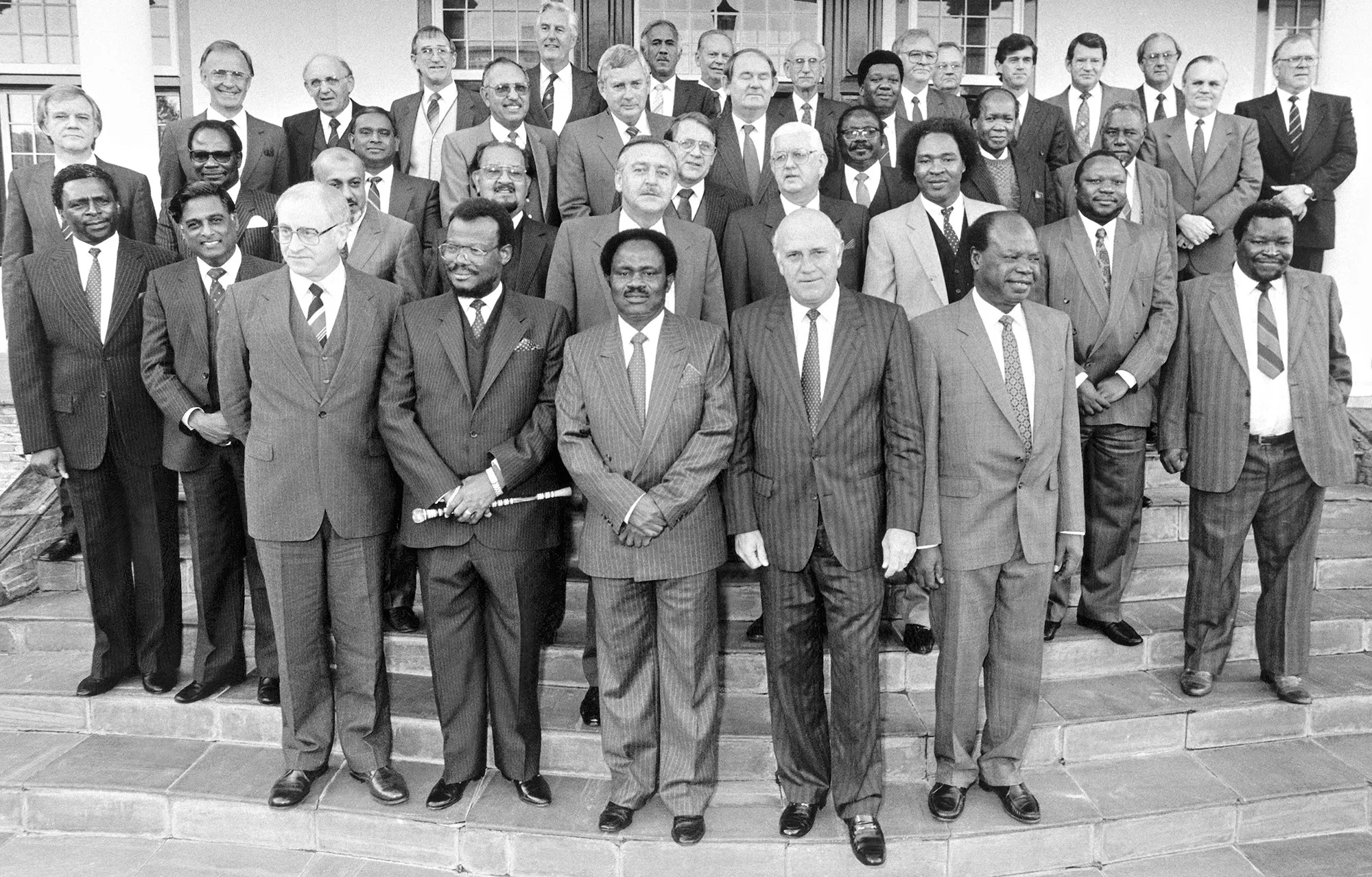

18 June 1990. South Africa. Constitutional negotiations. South African State President FW de Klerk meets with the Chief Ministers and Commissioners of the Homelands. Front row from l-r: Adriaan Vlok (Minister of Law and Order); Mangosuthu Buthelezi (Kwa-Zulu); Nelson Ramodike (Lebowa); FW de Klerk and Prof. Hudson Ntsanwisi (Gazankulu). Enos Mabuza (Kangwane) is in the second row, far left and SJ Mahlangu (KwaNdebele) is third from the right. (Photo: Gallo Images)

Glenn Frankel, writing in The Washington Post said of him, “For years, Mr. de Klerk insisted that apartheid was in its origins ‘an honorable vision of justice’ that over time had proven unworkable and unjust. He characterized the system as a mere mistake rather than a machine of brutal repression that had denied the vast majority of South Africans the most basic human rights. But in August 1996, he apologized to the country’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission for the ‘pain and suffering’ the regime caused.

“Still, the legacy of the apartheid years trailed him. In 2007, Eugene de Kock, an apartheid-era police commander who headed a death squad that targeted anti-government activists, said Mr. de Klerk’s hands were ‘soaked in blood.’ He accused Mr. de Klerk of approving gross human rights violations, a charge the former president vehemently denied. ‘I have not only a clear conscience; I am not guilty of any crime whatsoever,’ Mr. de Klerk said during a news conference in Cape Town.” DM

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

A well written and even-handed article. Thank you.

Thank you for a well researched and personally observed piece which clearly shows an honest and even handed approach to a complex subject.

Thank you for the article. May his soul rest in peace

I still remember my incredulity when listening to that 2 Feb speech.