It’s still early in the morning when dietician Katie Pereira-Kotze settles down at her computer in St Albans, just north of London.

Pereira-Kotze worked for the Western Cape health department before moving abroad in 2019. She’s now completing a doctorate in public health at the University of the Western Cape.

This morning, another day of trawling through academic research as part of one of her latest studies stretches out before her – at least according to the oversized piece of paper marked “workplan” next to her desk.

Suddenly, Pereira-Kotze spots a WhatsApp notification on her phone from back home in South Africa. She opens the app.

“Do you think this is something?” someone has just asked in a WhatsApp group of fellow PhD students.

Accompanying the text is a screenshot of an online webinar advert sponsored by a popular food and beverage company. It features prominent branding for two of the firm’s cereals for babies six to 12 months of age. If families attend, the ad promises, they’ll get to speak to a nurse about issues such as infant nutrition.

“If you have little ones, you do not want to miss this virtual conversation,” the announcement boasts. “You could win one of four R500 Shoprite vouchers just for attending!”

To the untrained eye it seems innocuous. Still, the message’s sender suspects something more sinister.

Pereira-Kotze does, too.

She forwards the message to other nutrition experts in a flurry of texts and emails. Finally, University of the Western Cape nutrition researcher Tamryn Frank replies, Pereira-Kotze remembers.

“We have to do something about this.”

Pereira-Kotze thinks of that gruelling PhD work plan sketched out beside her desk.

It will have to wait.

Infant formula’s long and complicated history

/file/dailymaverick/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/MC-Frontline-advert-and-protest-poster-1.jpg)

Infant formulas mimic most but not all of breast milk’s characteristics, New York University nutrition professor Marion Nestle writes in her book Food Politics. Still, only breast milk contains antibodies that protect infants and young children from diseases such as pneumonia, diarrhoea and even asthma.

Practically, formula is also harder to use safely than you’d think.

You need the money to buy it and the clean water to make it – plus more for keeping bottles and nipples sterile to stave off bacteria that can put babies at risk of deadly infections. For reasons like these, young infants who are not breastfed in the Global South are about 10 times more likely to die from diarrhoeal disease compared with those who are given breast milk, a 2011 BMC Public Health review of nearly three decades of research found.

The World Health Organization (WHO) now recommends that all babies – even those born to HIV-positive moms – are exclusively breastfed for the first six months of life: no porridge, no formula, no water.

Still, for decades, corporations aggressively marketed infant formula to families in the Global South, Nestle and others have documented – despite evidence emerging as early as the 1930s that it risked their babies’ lives.

In fact, infant formula came to South Africa before democracy did. A 1975 black-and-white magazine advert features a happy-looking baby alongside a can of Nestlé’s Lactogen – the tin’s contents spelt out in English and Afrikaans.

“Lactogen,” the ad proclaims, “is the very best milk for your baby.”

That’s not true, of course, and by 1975 science was well on its way to proving this, several studies show.

Decades later, however, the story of infant formula in South Africa would be complicated by the HIV epidemic, during which free formula was provided to HIV-positive mothers to prevent the transmission of the virus to babies via breast milk – in keeping with the science of the time.

But HIV science and HIV treatment have come a long way. In South Africa, anyone who is diagnosed with HIV – including those who are pregnant – can now start treatment immediately. Babies born to HIV-positive moms are also given medication to prevent contracting the virus via breast milk.

It’s why the WHO and the Health Department now encourage all HIV-positive women on treatment to breastfeed their children except in rare cases where a doctor has advised against it.

Almost one in five women in South Africa are living with HIV, according to the latest national survey.

In 2019, almost 30 out of every 1,000 babies born alive died before their first birthday in South Africa. This is nearly five times as many as in the US during the same period, World Health Organization data show.

Promoting infant formula is illegal but to date no company has been prosecuted

Eventually, the globe got wise to formula company tactics. In 1981, the WHO introduced the first international marketing codes on breast milk substitutes. Three decades later, in 2012, South Africa amended its Foodstuffs, Cosmetics and Disinfectants Act to bring the country in line with WHO regulations. The regulations came into force three years later.

The act bans any promotion of infant formula outright and places restrictions on the marketing of other infant and toddler foods. It also bars companies from using gifts to boost infant formula sales and from providing nutritional advice to the public directly, for example. To prevent enticing families with cute packaging, the law regulates not just what’s in these foods but also what’s on the label.

An image of a sun with eyes on a can of formula? Contraband. A bunch of grapes with arms and legs on porridge? Illegal, explains a Health Department guide for corporates.

South Africa’s policies to curtail the zealous promotion of infant formula are, on paper, so good that they recently earned the country the equivalent of a distinction in a recent WHO review. In practice, however, the policies haven’t kept up with social media, while enforcement remains poor and underfunded and virtually non-existent in rural areas.

Those who violate the act could face up to two years’ imprisonment and fines. Still, not a single corporation has been prosecuted for violating South Africa’s marketing code for infant and toddler foods in the law’s nearly 10-year existence, a recent study in the International Journal for Health Equity found.

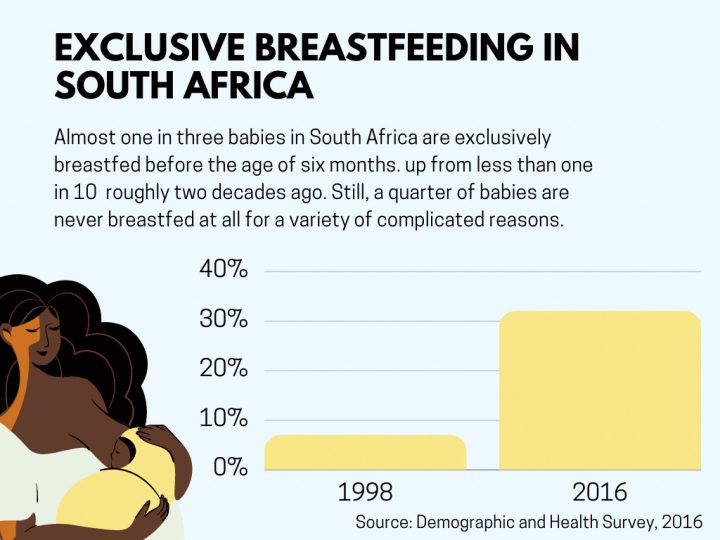

And in a country of low levels of exclusive breastfeeding and high rates of infant deaths, just 200 or so ordinary citizens – Pereira-Kotze estimates – might be South Africa’s only real defence against corporates looking to dodge the law and put babies at risk.

David versus Goliath: Meet South Africa’s citizen sleuths

Back in St Albans, Pereira-Kotze has put her studies away and begun her investigation. She clicks open a folder on her computer, revealing a library of guidelines, forms and regulations.

The first step in her probe: figure out what section of the act the webinar has violated.

As a dietician, Pereira-Kotze has spent nearly two decades as a citizen sleuth, sussing out violations of South African law, and tracking transgressions of the WHO code across Africa and Asia.

She’s now a resource for colleagues and even friends who think they might have spotted untoward marketing of baby and toddler products.

“They’ll send me a link or an email and ask, is this a violation?” Pereira-Kotze explains. “If it is a violation – and if I have time – I’ll ask if they want me to report it, or they’ll take it forward, or they’ll ask for help to report it and we’ll do it together.”

She continues: “I’m trying to upskill other people because monitoring violations is kind of this ad hoc, word-of-mouth procedure.”

Environmental health officers are meant to enforce the 2012 regulations, but they are also charged with monitoring everything from food safety to public smoking bans. It’s a tall order for the roughly 800 environmental health officers employed in the public sector nationally as of 2015.

Dieticians and nutritionists are also trained to spot violations but are likewise scarce. To plug the gap, dieticians like Pereira-Kotze have trained other workers such as midwives and peer counsellors on code enforcement.

Today, it can take between 15 minutes and more than an hour for Pereira-Kotze to figure out whether something violates the act, fill out the paperwork and compile the evidence required by the Health Department. The form the department requires isn’t widely available online and isn’t on its website, she says.

She uses a copy from a 2019 Western Cape health department training session. It has since been passed from inbox to inbox through a network of dozens of dieticians, breastfeeding peer counsellors and academics who monitor transgressions in their spare time.

“People who are interested in reporting violations manage to get hold of the form, submit it and share it with other people,” she explains. “It’s not ideal.”

Pereira-Kotze thinks the Health Department wanted to develop an online reporting tool based on the form at some point. Capacity issues, she guesses, probably got in the way.

Just one Health Department official and three dozen or so workers per province are tasked with enforcing the law – at least on paper

A Health Department official is tasked with monitoring violations of the infant formula code.

Partly because of dynamics like these, the department received, on average, only one violation report a month between 2016 and 2019.

Spokesperson Foster Mohale says the number of reported transgressions has fallen recently. In 2020, the department responded to just eight submissions.

The department did not provide a breakdown of where reports came from, but Pereira-Kotze, who has seen past statistics, says reports are often concentrated in urban areas, where dieticians are more likely to work. Rural areas – such as those in North West which lacked environmental health officers in 2015 – are underrepresented.

But the department’s biggest challenge, Mohale says, is policing violations on social media that remain largely unregulated. A December study by Pereira-Kotze and published in the British Medical Journal uncovered numerous alleged violations of South African law on social media. Social media companies like Twitter and Meta Platforms (Facebook), she says, should be aware of regulations – and enforce them.

Solving the case

Ultimately, Pereira-Kotze and Frank decide the August webinar – sponsored by Nestlé – contravenes South African law.

The Health Department agrees, telling Maverick Citizen in August that if Nestlé doesn’t pull the event “legal processes shall follow.”

Although Nestlé maintains that its event did not contravene the act, the company and the event host, Media24, ultimately cancelled the webinar.

Still, not every case Pereira-Kotze cracks turns out so well. She submitted another violation to the Health Department weeks ago with no word back. Meanwhile, Nestlé held a virtually identical event in March with no censure. Still, she thinks widespread media attention helped put the brakes on the firm’s latest webinar.

“This international code has been around for 40 years and it clearly states that breastmilk substitutes are not allowed to be promoted,” Pereira-Kotze says. “Companies know what they should be doing but they have the budget, they have the power, they have the resources, so they find ways to promote their products.”

In 2019, the Nestlé Nutrition Institute attempted to sponsor a free breakfast symposium on breastmilk for healthcare workers, which was also deemed to have violated national regulations after healthcare workers flagged it. The department eventually agreed and the event was cancelled on the day.

The institute is an independent non-profit research organisation but according to its website it “drives progress by sharing research conducted by Nestlé [the company]”.

You can’t just legislate change

Globally, 136 countries have translated the WHO’s 1981 code on baby formula marketing into local laws – about a dozen have done so in the past three years, according to a 2021 WHO report. Poor enforcement, however, is rampant in many countries.

So are laws like South Africa’s really enough to outwit companies and help families choose to breastfeed over formula?

To find out, Yale University researchers reviewed more than 80 studies on breastfeeding in South Africa. Their research review, published in the International Journal for Health Equity, found that although violations of the 2012 regulations continue, the reasons women don’t breastfeed are complicated. Families pressured some women to introduce solid foods too early, the review found, while others can’t continue breastfeeding while returning to work. Some women didn’t know the dangers of infant formula while some living with HIV and on treatment still think, mistakenly, that breastfeeding will put their babies at risk of HIV infection.

Enforcing South Africa’s ban on infant formula marketing may be necessary to increase breastfeeding rates in the country, the researchers concede, but it’s unlikely to be enough to help women overcome socioeconomic barriers to breastfeeding.

Pereira-Kotze’s doctoral research now focuses in part on the challenges informal workers such as domestic workers face in having healthy pregnancies and trying to breastfeed, including a lack of maternity leave, let alone paid leave.

“As a country, we know what we should be doing to help support breastfeeding… yet mothers are giving babies [formula] and not receiving the support and protection they need to breastfeed,” she says. “Then there are these strong influences from powerful companies that have lots of money.”

She concludes: “It’s an injustice.” DM/MC

Full disclosure: In 2021, Laura López González completed a monthlong editing consultancy with the Healthy Living Alliance (Heala). Heala has previously advocated around the R991 regulations.

[hearken id="daily-maverick/8851"]

Only breast milk contains antibodies that protect infants and young children from diseases such as pneumonia, diarrhoea and even asthma.

(Photo: Dudu Zitha / Gallo Images)

Only breast milk contains antibodies that protect infants and young children from diseases such as pneumonia, diarrhoea and even asthma.

(Photo: Dudu Zitha / Gallo Images)