BOOK EXCERPT

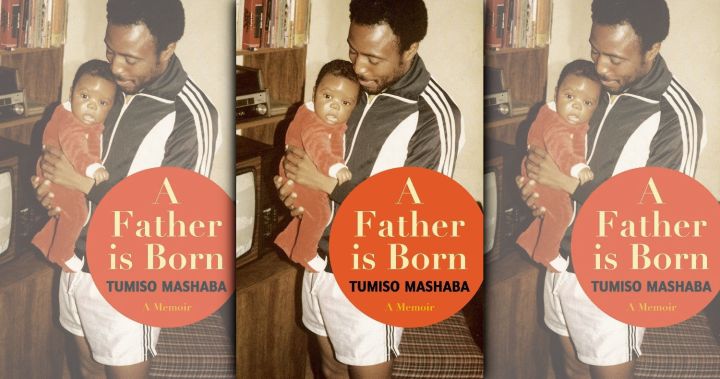

Will he repeat the sins of his father? Find out in Tumiso Mashaba’s memoir ‘A Father is Born’

The death of Neo ‘Snowy’ Mashaba at age 55 provoked an intense emotional reaction in his son, Tumiso, the author of this moving portrait of a relationship between a father and his boy.

Tumiso’s father was a distant and often brutal presence in his childhood. Why, then, this grief? What does his reaction mean, now, as a father to his own children?

Covering themes of black masculinity, generational trauma, toxic masculinity, infidelity, abuse, suicide and mental health, Mashaba creates a gritty backdrop of modern South Africa.

Author Niq Mhlongo calls this memoir ‘gripping, poetic, vivid and deeply entertaining.’

Here is an excerpt.

***

I went through the remainder of my second year at varsity with a sense of restlessness, a feeling of winding down. I was doing a four-year degree, two years full time and the other two part time, with a dissertation submission at the end. My two full-time years were coming to an end and I no longer felt like being at varsity or at res. By the end of the year I had no real home to go back to. My mother had moved out. It was just me, my father and my baby brother Tumelo. My mother would come by sometimes to check up on us. She was moving from place to place, trying to sort out her life. She kept some of her belongings, clothes and furniture, in the care of family and friends.

I spent the better part of those holidays out partying with friends and coming back home only to sleep at night. There was nothing that my father could say or do to me. He had forsaken his moral high ground by having an extra-marital affair. That December we all celebrated Christmas and New Year’s Eve at different places and with different people. Broken up.

***

Even though my father was bitter he was still hopeful that my mother would come back one day.

‘Your mother is mad, that one. She needs to really stop this behaviour of hers,’ he would tell me in passing. In his mind she was going through some silly mid-life crisis and she needed to snap out of it. It was only in May of the new year, when my mother bought herself a big, three-bedroomed, face-brick house in Etwatwa, Daveyton, that my father realised that she was never coming back.

I had never seen or heard my father cry, not even when Tshepo passed away. But one night after we had all gone to bed I heard him cry out, painfully and desperately, from his room. I could hear him try to suppress the cry but the emotion he was feeling must have been just too intense for him to stop. I think that night was his breaking point. It was very uncomfortable to hear such an outpouring of grief from my father. It showed me that he was human after all. I felt sorry for him. I wished that I could reach out to him. But there was nothing I could do. I couldn’t burst into his room and ask him if he was OK.

His moment of vulnerability felt important, as if he were coming to terms with all that he had kept shrouded up inside of him all these years. I could not take that away from him, as painful as it was to hear a grown man bawling.

I also could not undo the past. I could not go back in time and tell my mother to give her marriage a second try. My blessing on her decision to leave the marriage and to forge a new life without my father could not be undone. In the morning we just went about our lives as usual.

***

At first my father tried to hold on to the house, but he was struggling to keep up with the repayments on his own. So he and my mother, who were married in community of property, agreed to sell the house and to split the proceeds equally while their divorce was being finalised. The two had resolved to be amicable with each other for the sake of me and Tumelo.

But the one thing that my father was not prepared to compromise on was Tumelo. He told my mother that there was no way she was going to get full custody of him. He told her that her life was unstable and she was not going to unsettle Tumelo’s life as well. I had now moved out of home and was trying to make it in the media industry as a working young man in the busy streets of Johannesburg. So I was the least of my father’s concerns. Tumelo was the only person he had left, and he was determined to hold on to him no matter what. He was also determined to give him a stable home and to ensure that his schooling was not interrupted.

My mother did try to get full custody, but my father was adamant that it was not going to happen. He was actually quite threatening. He did not say in so many words what he might do if my mother continued to try to gain full custody. But one could deduce from his language and tone that he meant business, and that he was prepared to do anything to stop Tumelo being taken away from him.

My father’s attitude towards my mother had now evolved into sheer hatred. He stopped referring to her as ‘your mother’ and started calling her ‘that one’. At the time my father had a 9 mm calibre firearm and my mother feared that if he were to be pushed to the limits he might be tempted to use it, and so she relented and agreed to see Tumelo only on weekends.

But bitter and angry as he was, my father used this period to get right as a parent with my little brother Tumelo what he got wrong with me and Tshepo. At first, after the old house was sold, he moved to a flat with Tumelo. A few months later he bought a big stand-alone house, which would become Tumelo’s new and permanent home. My father’s life now revolved only around his work as the principal of Sechaba Primary School and around Tumelo’s needs and well-being. In a sense he was actually now the sole parent because my mother was still figuring out her new life.

My father attended all the parent-teacher meetings at Tumelo’s school. My mother would be present only sometimes. He supported Tumelo’s extra-curricular activities too. They went on holidays together to places like Durban and Cape Town. When Sechaba had outings, he would take Tumelo along with him.

And he never raised a hand against him. Not even once. He nurtured him with nothing but positivity. He cooked for him every day. He helped him with his schoolwork. He framed all his merit and achievement certificates and he proudly hung them up on the walls around the new house. I started warming to him. He was no longer the same father that had raised me and Tshepo. He was maturing into a better father. Everyone deserves a second chance, I thought. DM/ ML

Tumiso Mashaba is a journalist, writer, producer and entrepreneur. In 2011 he was awarded the United Nations Foundation prize for his documentary, Forging Utopia, about refugees. A Father is Born is published by Jonathan Ball Publishers (R270). Visit The Reading List for South African book news – including excerpts! – daily.

[hearken id=”daily-maverick/8832″]

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

Comments - Please login in order to comment.