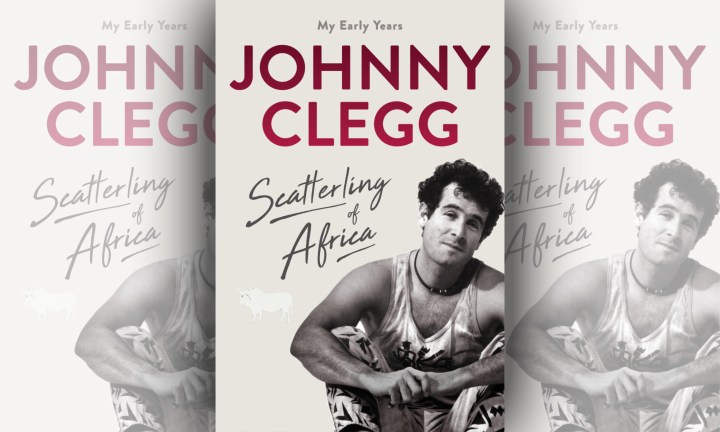

BOOK REVIEW: SCATTERLING OF AFRICA

It’s not black and white: The grey world that shaped Johnny Clegg

Long before he was known as the white man who sang and danced like a Zulu, the world-famous musician grappled with issues of race in his fight to become a truly free human being.

Johnny Clegg’s immersion into Zulu culture and traditional music that catapulted him into superstardom has always raised uncomfortable questions about the appropriation of African culture and gaining commercial success from it.

But long before the world knew Clegg as a white man who sang and danced like the Zulu people, he had taken a personal journey to break down racial barriers and stereotypes. He immersed himself in Zulu culture to a depth that, it could be argued, even most urban Zulu people have yet to attempt.

His journey into the world of the Zulu people came to define Clegg, a Jewish man born in England on 7 June 1953, earning him the moniker he detested, “the White Zulu”.

In his recently published book Scatterling of Africa – My Early Years, Clegg writes about how his stepfather’s pain of dealing with his own racial identity and search for validation and authentication shaped the man that he himself became.

The late music icon, who died of pancreatic cancer in July 2019, gives a fascinating and detailed account of his early years that shaped his early consciousness about issues of race, racial prejudice and segregation.

Clegg spent his childhood in three African countries – Zimbabwe (then known as Rhodesia), Zambia and South Africa, where he eventually spent more than 50 years of his life.

“Zambia had an immense impact on my young mind. As a child I did not think about the divisions around me. I was inexperienced in life. But as I grew older, I became aware. White adults always had jokes or cultural judgements in social gatherings about blacks or Indians or coloured people. I became aware of a sense of cultural superiority that white people had, which was reinforced by ideas about technical and scientific advancement, as well as wealth and its trappings. Spending close to two years in Zambia was formative for me and, young as I was, it was an eye opener,” Clegg writes.

He traces his early intrigue about race to his stepfather’s “fascination with the grey areas of apartheid”. Dan Pienaar, a crime reporter on a Johannesburg newspaper who married Clegg’s mother Muriel, “was technically a coloured person, sub-group Malay coloured, ‘passing for white’.

“Through his own internal struggle, Dan exposed me to the world of traditional urban black culture when he took me with him into the townships to see the other South Africa.

“Somewhere, subconsciously, I believe that Dan’s hidden pain in dealing with his racial identity subterfuge became a part of my own identity,” he writes.

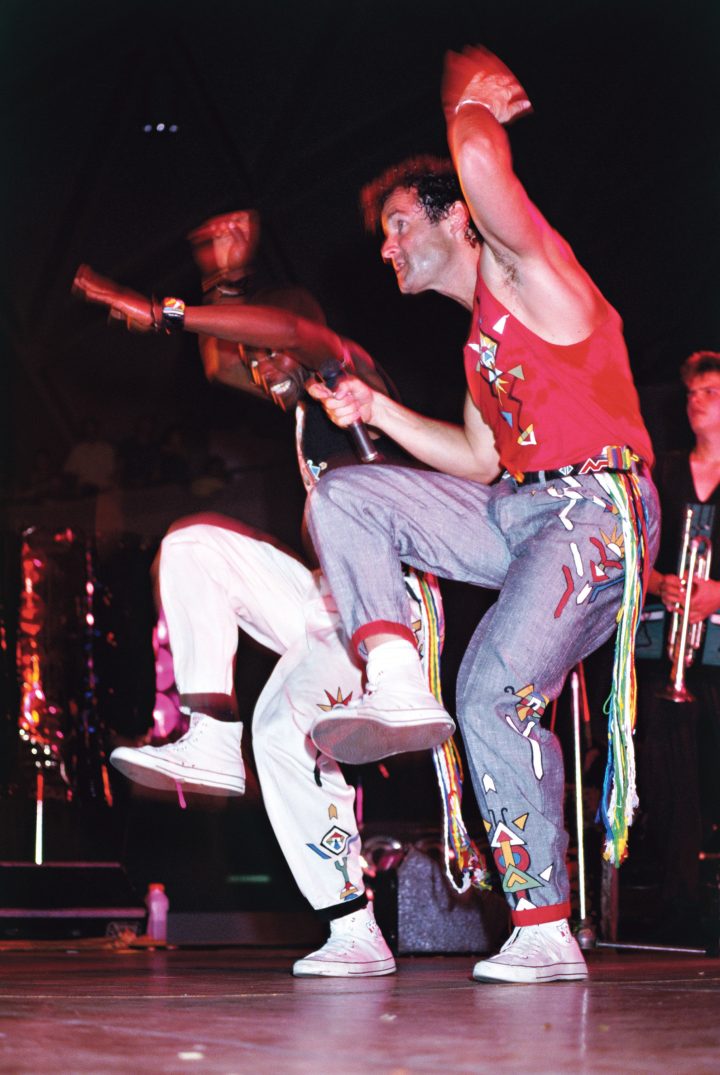

Johnny Clegg and Juluka. Clegg was born in England but lived in Zambia, Zimbabwe and later South Africa. (Photo: Gallo Images)

It was perhaps this early confrontation with the complexities of race and identity that laid the foundation for him to strike up lifelong friendships across racial boundaries with men such as Charlie Mzila and Sipho Mchunu in the late 1960s.

Both Mzila and Mchunu were older than Clegg and they welcomed the curious teenager into the rich world of Zulu culture and music. His foray into the world of the Zulus is what eventually catapulted Clegg into the spotlight as a musician. Clegg was accused in some quarters of cultural appropriation for his own benefit, with questions raised about whether he used his closeness to Mchunu and other Zulu musicians to carve out his own path to fame.

This may seem justified, especially in a country still battling to shake off decades of racial segregation and stereotyping that sought to put people into boxes based on their race and colour.

But in this book, Clegg subtly puts paid to this misguided notion, just as he did in life.

He notes in the introduction that “my primal motivation to enter the world of Zulu migrant worker culture was not driven by a personal statement against apartheid”.

“I was 14 years old and stumbled on Zulu maskandi guitar music and, later, war dancing, and this brought me into conflict with the authorities. I was not looking for politics. Politics found me.”

He reflects that, for him, the laws of cultural and racial segregation were “just potholes in the road that the world threw at me, testing my resolve and, like the Zulu migrants I admired, being arrested – and I was arrested many times, the first when I was 15 – for me was ‘cool’ because, like them, I had to deal with the daily obstacles the authorities placed in front of us.”

Clegg outlines his endless battles against the authorities trying to uphold a system that ruthlessly suppressed any attempts by people to integrate across racial lines simply as humans and not as master and servant. So complex was this journey that even something as normal as purchasing a bus ticket to Zululand became a complicated thing that drew the interest of the authorities.

Although the journey into the lives of Mzila, Mchunu and the Zulu people was riddled with challenges – including arrest by police, harassment by security guards at hostels where his friends danced and being scorned by whites – Clegg tells the stories with humour and context.

He captures the world that welcomed him behind the high walls of the single-sex male hostels in colourful detail. He presents the lives of the men trapped in the segregated hostels with dignity and without judgement.

The story is not presented simply as an account of a white youth fascinated by the world of black men with different cultural values, norms and practices; instead, Clegg provides a somewhat scholarly take on the lives of the men who embraced him as one of their own. The book reads in part as a social anthropology study into Zulu migrant and cultural life, which is not surprising, given that Clegg qualified and lectured at Wits University in that subject.

In places, Scatterling reads like a memoir, with the author reflecting on incidents and decisions, trying to define his life’s philosophy.

As the author says in his introduction: “The shape of my story is not strictly chronological or linear. It winds through canyons of neural pathways with mental sinews hardened by repetition of days.

“This flickering landscape is where I collect and make sense of all the incidents and the meanings that are attached to this gnarled mind’s eye like some ancient cataract. Existential archaeology.

Digging around old geographies and awkward sites of personal struggle, sifting through passing moments that carried hints of tomorrow and its promises, and then failed.” Mukurukuru Media/DM168

Johnny Clegg’s Scatterling of Africa – My Early Years is published by Pan Macmillan.

This story first appeared in our weekly Daily Maverick 168 newspaper which is available for R25 at Pick n Pay, Exclusive Books and airport bookstores. For your nearest stockist, please click here.

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

Comments - Please login in order to comment.