This month, Maverick Citizen revealed that a plan drafted by the sugar industry and the government to revive the ailing sugarcane sector might have been accompanied by an agreement to propose a three-year moratorium on increases to the health promotion levy.

The levy, which only applies to select drinks, reduced the actual average volume of sugary beverages South Africans bought by about 5% in its first year alone, according to an April study published in The Lancet medical journal. When scientists modelled how much sugar South Africans would be drinking if the health promotion levy never happened at all, they found the tax slashed empty calorie consumption from sugary drinks by about a quarter.

Numerous research reviews have linked the consumption of sugar-sweetened beverages to an increased risk of weight gain and diabetes, which is the second leading cause of natural death in South Africa.

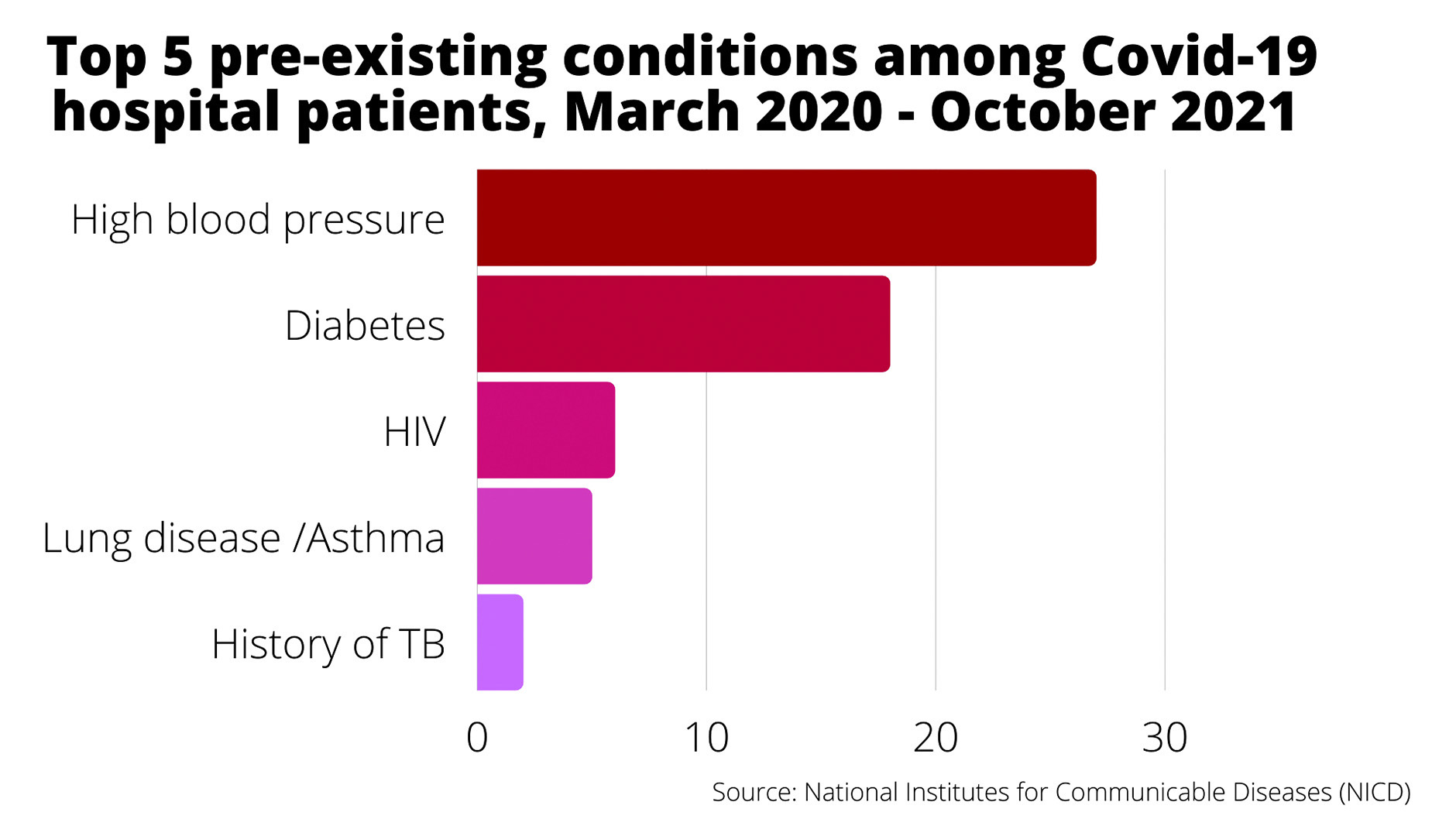

Diabetes is also a leading risk factor for serious Covid-19, according to data from the National Institute for Communicable Diseases – as is high blood pressure, which can be linked to obesity.

An agreement in principle but not on paper?

The Department of Trade, Industry and Competition and the Department of Agriculture, Land Reform and Rural Development spearheaded the sugarcane recovery plan. Still, not a single health department official or independent public health expert was included in the consultations for or the drafting of the document.

Health Department spokesperson Foster Mohale said the department was not even aware of the consultations.

/file/dailymaverick/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/MC-Sugar-Tax.jpg)

Ultimately, industry actors including the Beverage Association of South Africa (BevSA), the Consumer Goods Council of South Africa and the South African Canegrowers Association drafted the document. A three-year freeze on levy increases does not appear in the plan itself. Instead, Canegrowers Association CEO Thomas Funke told Maverick Citizen that the moratorium forms part of the plan’s strategy to create up to a three-year window to allow the sector to restructure.

Healthy Living Alliance head Nzama Mbalati has slammed what he says appears to be a possible agreement in principle between industry and the Department of Trade, Industry and Competition to weaken the health promotion levy. Only National Treasury has the power to raise or lower the health promotion levy. Still, Mbalati says the alliance will be sending formal letters to the trade and agriculture departments to seek clarity on the Canegrowers Association’s claims – and whether the departments have entered into any other agreements with industry around the tax. Mohale said his department would seek clarity from Treasury.

Meanwhile, the sugar sector’s latest move to derail the levy is part of a larger trend documented by South African researchers in which it seeks to influence healthy policy behind closed doors and through professional associations.

“When you read the [sugarcane] master plan in its entirety, it doesn’t have any moratorium on increasing the tax,” Mbalati told Maverick Citizen. “It’s disastrous if the government has entered into a back-door agreement with the sugar industry, but the document that they’ve made available publicly doesn’t in any way cite any form of a moratorium on the health promotion levy.”

He continues: “If the government has actually entered into that kind of dodgy deal – that is really putting the private interests of industry ahead of people’s.”

The Department of Trade, Industry and Competition did not respond directly to previous questions asking it to confirm Funke’s comments, or whether such a ban is the department’s official position. Instead, departmental spokesperson Bongani Lukhele said all proposals contained in the plan would be put before relevant departments.

When asked to verify claims by the Canegrowers Association, Department of Agriculture, Land Reform and Rural Development spokesperson Reggie Ngcobo said the South African Sugar Association, one of the plan’s authors, was “better placed to respond”.

A good policy keeps getting weaker

In March, Treasury said it would undertake its own assessment of the levy’s impact before making any increases. Previously, it implemented its first and only increase in the levy, of less than half a cent, in 2019.

But Mbalati warns that each year without an increase, the levy’s power to dissuade people from buying sugary beverages weakens.

/file/dailymaverick/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/MC-Sugar-Tax_2.jpg)

Already, the 11% levy is much lower than the 20% Treasury originally proposed in 2016, in large part because the government was sympathetic to industry concerns about job losses.

“For almost all [ANC MPs], the argument was won for a sugary beverages tax in the earliest of stages,” ANC MP and chairperson of the Select Committee on Finance, Yunus Carrim, told researchers in a 2020 report.

He continued: “The issue then became for us: We are going to agree on the sugary beverages tax, but how do we decide on how much of the sugar content and rate, and how do we do this in a way that avoids job losses?”

A 2015 Wits University study predicted a levy of 20% could have eventually reduced the prevalence of obesity in the country by about 3%.

Has the levy really led to job losses?

The Department of Trade, Industry and Competition admits that the sugarcane industry has been in decline and has seen 25% reduction in annual sugar production in the past 20 years and a 60% reduction in sugarcane farmers over the same period.

Still, whether or how the health promotion levy has contributed to actual job losses remains impossible to verify. To date, no peer-reviewed research on this in South Africa has been published. Meanwhile, a 2019 study published in the journal Globalization and Health found the industry had misrepresented European data on job loss related to health taxes in public submissions to MPs like Carrim.

The study argued that, for example, one industry actor had neglected to mention that a 2014 report had found there was a general lack of data on whether food taxes led to job cuts but no evidence of short-term job losses in Denmark, Finland or France after food levies were imposed there.

Results were mixed in Hungary.

In the absence of peer-reviewed data, figures on job losses tied to South Africa’s health promotion levy come from industry or a recently released report commissioned by the National Economic Development and Labour Council (Nedlac) that suggested that the sugar tax led to 16,621 jobs being lost in the sugar sector by 2019.

In a country where about 26,000 largely Indian, coloured and black people die annually from diabetes, the Nedlac report does not include any economic analysis of the levy’s health benefits, such as better health among workers or reduced healthcare expenditure for workers, employers or the government.

Who is paying sugar’s real price?

Poorer South Africans buy, on average, more sugary beverages. Before the health promotion levy was introduced, people in households like these drank, on average, nearly one 300ml sugary drink a day. Unsurprisingly perhaps, a 2009 study in The Lancet found that South Africa’s burden of non-communicable diseases rests disproportionally on the shoulders of the urban poor.

But this consumption isn’t a coincidence. Globally, food companies spend billions of dollars marketing their products, points out City University of New York public health professor Nicholas Freudenberg in his book, Legal but Lethal: Corporations, Consumption and Protecting Public Health.

/file/dailymaverick/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/MC-Sugar-Tax-Graph2.jpg)

In a 2012 presentation to investors, an SABMiller executive showed a slide on the South African beverage market with the words “One country... two realities” across the top.

Underneath the heading was a selection of photos. Half depicted affluent South Africans in front of a beautiful home or sitting in their family lounge. The other half showed children in a township and next to informal housing and were meant to depict the country’s lower Living Standards Measures (LSMs).

LSMs are used by marketing companies to divide the South African population according to their average income and the kinds of goods they consume.

Above photos meant to represent the country’s lowest LSMs, an SABMiller executive had emblazoned the words “Main Market Opportunity”. Almost half of this “main marketing opportunity” lives on less than R3,000 a month in household income, and no home included in these designations even broke the R7,000 monthly income mark.

The health promotion levy cut the amount of sugar poor households bought by about 8 grams per day – almost four times the reduction seen in more wealthy homes, found the April study in The Lancet. However, the authors admit the research couldn’t track changes in purchases among the poorest communities.

Still, because poorer South Africans disproportionately feel the impacts of poor health from diseases like diabetes – think lost wages and an inability to access healthcare – researchers write that pro-poor dynamics like these hidden within the sugar tax data might make the levy socially progressive.

Back rooms and back channels

But Nedlac isn’t a space meant to discuss health policy. It’s a forum for labour, industry and government – and that might work in industries’ favour.

Safura Abdool Karim is a researcher with the South African Medical Research Council and Wits Centre for Health Economics and Decision Science (Priceless SA), where she has studied the tactics the food industry uses to oppose regulation.

One of them, she warned, is to shift consultations away from the public eye into spaces where public health experts either aren’t present or, worse, aren’t allowed.

“[Industry] tries to shift consultation to fora that have a level of exclusivity – you can see Nedlac as an example of that,” Abdool Karim told Maverick Citizen earlier this year.

/file/dailymaverick/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/MC-Sugar-Tax-Graph2_1.jpg)

The sugarcane recovery plan may be yet another illustration of this. The Department of Trade, Industry and Competition has confirmed that no independent health experts or members of civil society were present for its consultations with industry and the agriculture department that led to several industry associations penning the final sugarcane masterplan.

Even the Health Department has a standing meeting with the Consumer Goods Council of South Africa to talk about policy enforcement, Abdool Karim said. Traditionally, civil society has not participated in these meetings.

And it’s all perfectly above board – and not especially unique to South Africa or the food sector.

“Food companies use every means at their disposal – legal, regulatory and societal – to create and protect an environment that is conducive to selling their products in a competitive marketplace,” writes New York University nutrition professor Marion Nestle in her book Food Politics. “For the most part, food company strategies are standard economic practices and are legal.”

She continues: “Whether they are ethical or promote the health of the public is quite another matter.”

Abdool Karim said both food and alcohol lobby groups have used this tactic of shifting conversations away from places where greater transparency might be a legislative requirement, into arenas where the public may never know who agreed to what and how.

“Because [forums like these are] shrouded in secrecy and there’s a lack of transparency and representation, it lets [industry] run amok to argue for exactly what they want,” she said. “The reality is we wouldn’t know what they’ve done because it all happens behind closed doors.” DM/MC

Delay, dilute, delegitimise: How the food industry shapes what you eat and what you weigh

Wednesday | 3 November | 12pm SAST

Maverick Citizen journalist Zukiswa Pikoli in conversation with independent health journalist and editor Laura Lopez Gonzalez and public health lawyer Safura Abdool Karim. Register here to know more, know better: https://event.webinarjam.com/register/552/yyllob0l

01/11/2021 Civil society questions government’s ‘backdoor agreement’ with industry to stall sugar tax hikes.

(Photo: beveragedaily.com/Wikipedia)

01/11/2021 Civil society questions government’s ‘backdoor agreement’ with industry to stall sugar tax hikes.

(Photo: beveragedaily.com/Wikipedia)