On 26 April 1986, the Soviet Union’s nuclear reactor at Chernobyl (the site located in what is now northeastern Ukraine) exploded, as it lost its concrete/steel containment building, spewing radiation into the sky. It has now been announced that Viktor Bryukhanov, the man in charge when the explosion happened, died on 13 October at the age of 85.

Bryukhanov, a nuclear engineer, had also directed the construction of the reactor. That destruction at Chernobyl, the world’s worst reactor disaster, was one of several key events that triggered the collapse of the Soviet Union, along with its military debacle in Afghanistan and the country’s ongoing inability to match the ramping up of advanced military technology and spending by President George HW Bush’s administration in the US, the Soviet Union’s Cold War rival.

Collectively those events demonstrated a serious callousness towards the country’s population on the part of its leaders, as well as the hollowness of any hopes for serious evolutionary change emanating out of perestroika and glasnost — those twinned reforms of restructuring and transparency — that were Premier Mikhail Gorbachev’s efforts to stem the decay of the Soviet Union. For his part in the Chernobyl disaster, Bryukhanov spent five years in prison.

Up until he wasn’t a hero, and until he became the officially certified scapegoat for the explosion, the death and destruction, the release of radioactive clouds, the international panic and the ensuing declaration of a 2,500km² no-go zone around the stricken reactor, Bryukhanov had been a rising star of the Soviet system. He had received awards for his work, including the Order of the October Revolution, and medals “For Valiant Labour in Commemoration of the Centenary of the Birth of VI Lenin” and as a “Veteran of Labour” and a “Certificate of Honour of the Supreme Council of the Ukrainian SSR”.

Back in 1970, while he was still that man of great and growing promise, the country’s energy minister had given Bryukhanov the challenging plum assignment of creating a brand-new atomic power plant comprising four RBMK (water cooled, graphite rod moderated) nuclear reactors on the banks of the Pripyat River, in what is now Ukraine. At the beginning of the proposed development, Bryukhanov had suggested building pressurised water reactors instead of those RBMKs favoured by his superiors, but his bureaucratic betters disagreed, citing safety and economic grounds. (Shades of astronaut John Glenn’s possibly apocryphal, wry remark while he sat atop his Atlas rocket just before liftoff, that the whole thing had been built by low bidders?)

The New York Times noted of the government’s decision, “…[T]he Chernobyl plant’s construction manager, Mr. Bryukhanov had recommended the installation of what were known as pressurized water reactors, which were widely used around the world. But he was overruled in favor of a different type unique to the Soviet Union: four Soviet-designed, water-cooled RBMK reactors, which were nestled end to end in an enormous building.

“ ‘Among others, scientists, engineers and managers in the Soviet nuclear-power industry had pretended for years that a loss-of-coolant accident was unlikely to the point of impossibility in an RBMK,’ the historian Richard Rhodes wrote in Arsenals of Folly (2007), his book about the nuclear arms race. ‘They knew better.’ ”

Despite his objections, Bryukhanov tackled the near-herculean task of willing the entire facility into being, from scratch, down to all the accommodations and facilities needed for those doing the complex construction. Inevitably, like most power generating plants, construction took two years more than the original plans had called for (with inevitable delays arising from materials shortages or the need for inferior, defective materials to be replaced in the middle of construction).

The entire project finally began to draw to a conclusion seven years after construction had been launched, when the first of the four reactors went on-stream, on 1 August 1977. Two months later Chernobyl’s first generated electricity entered the national power grid.

There were, however, worrying signs of possible trouble with the plant right from the beginning. Bryukhanov reportedly failed to acknowledge a radioactive leak that occurred on 9 September 1982, when steam rose through a vent stack shared by reactors one and two. That event indicated that somewhere within the plant’s maze of tubing there was at least one broken pipe that had allowed radioactive coolant to be vented into the atmosphere. This first time around, however, the released radioactive contaminants spread 14km outward from the plant, reaching the town of Pripyat that had been built for the plant’s employees. Four years later, with the four reactors now online, the massive accident occurred.

Investigations into the 1986 accident determined that faulty protocols in the plant’s design and poorly trained personnel had caused the steam explosion and fires that erupted early in the morning of 26 April 1986, during a flawed safety experiment at the last of the installation’s four reactors. The resulting explosion destroyed the reactor’s steel and concrete roof and spewed tons of radioactive rubble 800m into the air.

As the UK’s Sunday Times described the scene, “At 1.24am on April 26, 1986, a safety test at the Chernobyl nuclear plant in Ukraine went catastrophically wrong. A huge explosion destroyed the fourth reactor, smashing open the roof and blasting tons of highly radioactive uranium into the atmosphere.

“Over the following days the toxic cloud drifted across Europe as far as Britain. The political fallout of the world’s worst nuclear disaster spread even further. It contributed to the collapse of the utterly discredited Soviet Union in 1991.”

The resulting radioactive cloud panicked millions around the world. Pre-internet and social media, they watched anxiously for more information on their televisions or looked to their newspapers for any guidance about what they possibly could do to deal with that radioactive cloud.

Describing the damage wrought by the explosion, National Geographic reported, “On April 25 and 26, 1986, the worst nuclear accident in history unfolded in what is now northern Ukraine as a reactor at a nuclear power plant exploded and burned. Shrouded in secrecy, the incident was a watershed moment in both the Cold War and the history of nuclear power. More than 30 years on, scientists estimate the zone around the former plant will not be habitable for up to 20,000 years.” Several documentaries and a new Russian docudrama, as well as a well-regarded HBO miniseries have been made about the circumstances and effects of the explosion.

At the time of Bryukhanov’s death, The New York Times noted, “Two workers died immediately, and 28 more fatalities, from radiation poisoning, were recorded within a few weeks. Even though some 350,000 people living in the area were evacuated, scientists estimated that an additional 5,000 thyroid cancers could be attributed to radiation exposure from the accident. ‘My father came home after 24 hours, and it looked like he had aged 15 years,’ Mr. Bryukhanov’s son, Oleg, said in an interview for a 2020 Flemish TV series, ‘Under the Spell of Chernobyl.’

“Wind spread radioactivity as far west as Italy and France, contaminating millions of acres of European farmland and forest and producing deformities in newly-born livestock [including fears of contamination of the Sami people’s reindeer herds — via the vegetation they consumed — in northern Scandinavia as well]. After the accident, the reactor core was enclosed in a concrete and steel sarcophagus, but even that proved to be structurally insufficient, and officials declared a 1,600-square-mile zone surrounding the plant to be uninhabitable indefinitely.

“ ‘You need to understand the real causes of the disaster in order to know in what direction you should develop alternative sources of energy,’ Mr. Bryukhanov told the Russian magazine Profil in 2006. ‘In this sense, Chernobyl has not taught anything to anyone.’ ” Until he died, Bryukhanov had insisted he and several other plant officials had been scapegoated as a result of ‘…a tissue of lies that distracted us from the search for the real causes of the accident.’

“ ‘…[I]n the night someone called Bryukhanov from the power plant to tell him that “something awful has happened — some sort of explosion,” ’ Mr. Rhodes wrote [in Arsenals of Folly]. ‘He rushed to the scene thinking he would have to deal with another steam-valve rupture, but when he saw Number Four ruined and smoking, fires burning on the roof, fire trucks everywhere, he said later, “my heart stood still.” He claimed he called Moscow for permission to order an immediate evacuation, without finding anyone in authority willing to believe that such an accident could happen to an RBMK,’ Mr. Rhodes continued. ‘Whether he contacted Moscow or not, he waited until four in the morning — three and a half hours after the explosions — to alert the authority nearest the plant, Kiev Regional Civil Defense, and then reported only the roof fires, which he told Kyiv would soon be extinguished.’ ” That turned out to be a colossal misapprehension of what was happening, obviously.

Astonishingly, after being released from prison after serving five years of his initial 10-year sentence, Bryukhanov actually reentered government employment, this time for the new nation of Ukraine, heading the technical department of its Economic Development and Trade Ministry. While he accepted his professional responsibility for the disaster, he always denied any criminal liability, arguing the explosion was due to those original design flaws dictated by those people in Moscow, as well as a failure of his bureaucratic superiors to provide enough equipment to measure radiation leaks, along with government red tape and confusion dividing responsibility between technocrats and Communist Party apparatchiks.

Astute readers will undoubtedly have noticed by now there are several lessons that may usefully be drawn from this disaster that may bear on South Africa’s own contemporary circumstances.

First of all, before the country embarks on any additional nuclear reactor projects to generate electrical power, most especially any coming out of Russia, it would be very useful to examine thoroughly the precise nature of the proposed technology and its long-term safety record — this, in addition to all the political repercussions, the lengthy construction timelines needed, the likely time lags between plans and completion, and the huge cost factors (and those inevitable cost overruns), and demands for resources that are necessarily involved in any such projects.

Such factors must be weighed in comparison to alternative forms of electrical energy generation such as wind and solar, without tempting political biases to steer decisions.

Second, and more generally applicable to all manner of major projects with major risks attached to them, is the vexed question of divided authority between the people who actually understand the technology involved and those who have their bureaucratic and political interests at heart, in the event of accidents or other major disasters.

A corollary to this is to ensure any political masters such as non-specialist cadre deployees are not automatically interested in arbitrarily minimising potentially hazardous or disastrous events by fiat, and thus are reluctant to inform citizens and foreign neighbours of the possible problems or challenges.

Finally, there must be a political willingness to rely on those familiar with and knowledgeable about the technologies concerned to make the appropriate technological decisions, consistent with the nation’s political, financial and economic realities and in response to knowledgeable advice.

But, sadly, in a nation that increasingly seems incapable of properly maintaining and running its current network of electrical power distribution and power generating stations, identifying and recruiting the technologically skilled managers to tackle such positions and thus to make the hard decisions seems increasingly difficult to accomplish. Such a policy landscape allows for all manner of perfectly dreadful mistakes to happen to all of our detriments — over and over again. DM

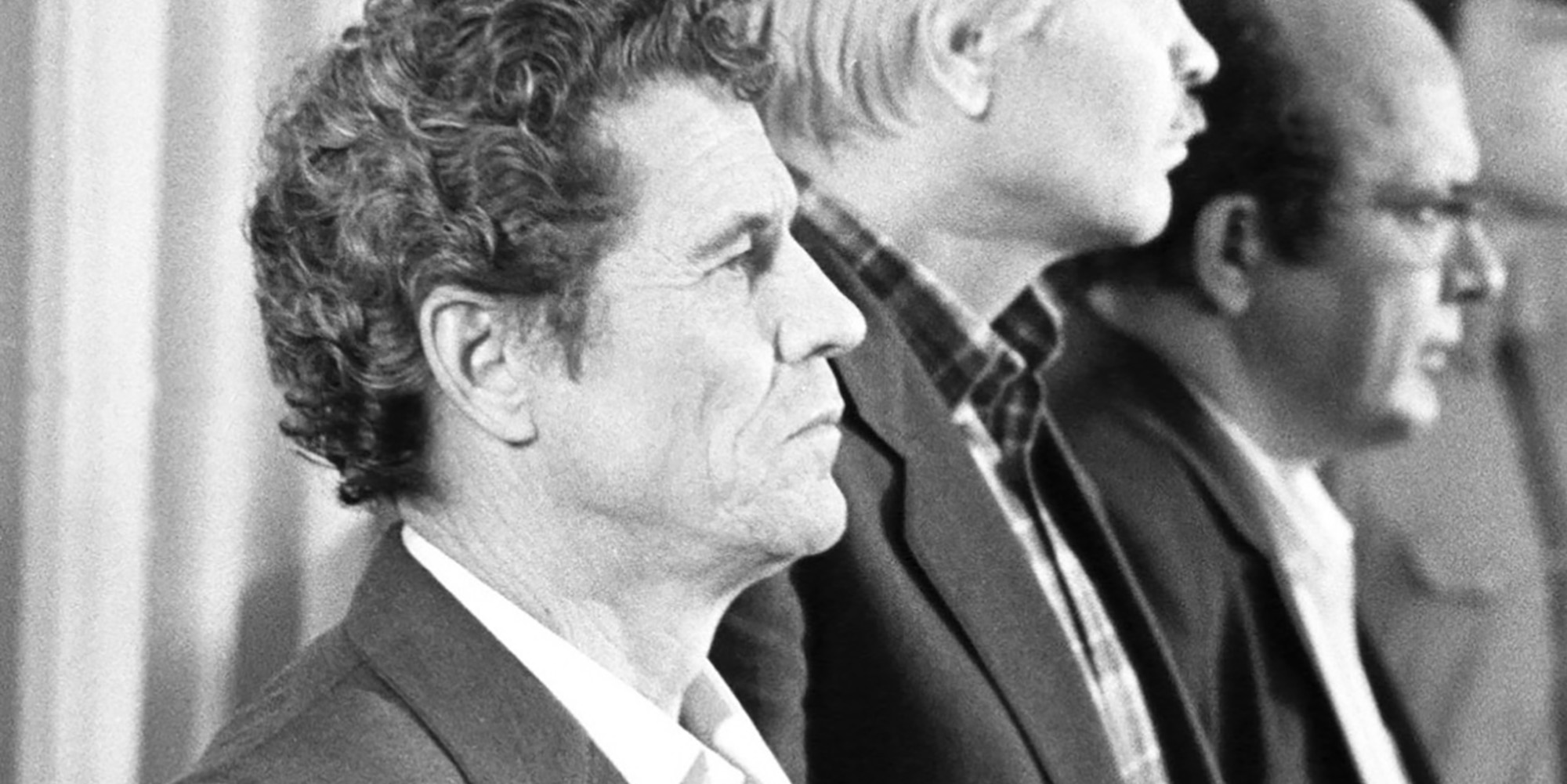

Viktor Bryukhanov, the man in charge when the Chernobyl explosion happened, died on 13 October at the age of 85. (Photo: Vladimir Samokhotsky / TASS)

Viktor Bryukhanov, the man in charge when the Chernobyl explosion happened, died on 13 October at the age of 85. (Photo: Vladimir Samokhotsky / TASS)