OLIVER TAMBO MEMORIAL LECTURE

OR Tambo, an ANC leader who understood every war ends with the antagonists sitting around a table

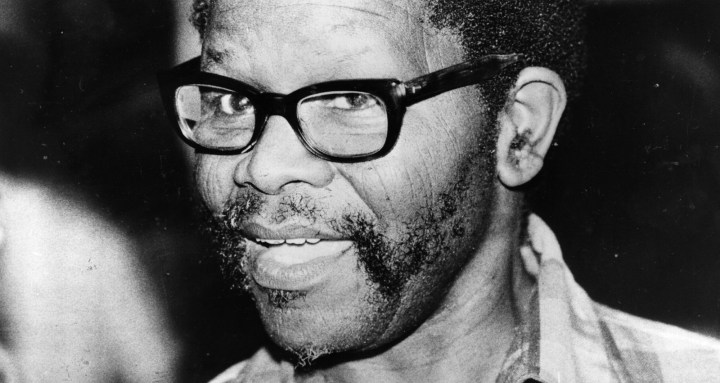

What has always fascinated me most about Oliver Tambo is how he managed simultaneously to travel the world as a suave-suited diplomat striding the corridors of international power and be guerrilla Commander-in-Chief in combat fatigues in the camps of Tanzania, Zambia and Angola.

The Undersung Hero was the title of my chapter for a 2007 book commemorating Oliver Tambo. Of course he was never undersung to his close friend and comrade Nelson Mandela who, when he walked out of prison, publicly saluted “my President, Oliver Tambo”.

The hundreds of millions across the world watching on television during those momentous days in February 1990 might have been forgiven for wondering why? Who was “his” president?

For the name “Oliver Tambo” did not trip off the tongue of a world enthralled by the courage, the resilience and above all the wisdom and dignity of Mandela who had spent nearly ten thousand days in the prime of his life in gaol.

But Mandela knew only too well what all of us involved in the bitterly hard decades of anti-apartheid struggle, inside and outside South Africa, did: that his own eventual freedom and that of his people, owed so much to Oliver Tambo’s leadership of the ANC during 30 years of exile, based mainly in Lusaka, his family in London.

There I met OR, saw him speak on platforms organised by the British Anti-Apartheid Movement, and was struck by his modesty and old-fashioned sense of courtesy. Soft-spoken and eloquent rather than charismatic, austere rather than flamboyant, speaking with persuasion rather than oratory, exuding a steely, impressive and powerful but warming presence.

Although Mandela was the iconic figurehead of the freedom Struggle, OR Tambo was actually the leader, after going into exile when the ANC was banned in 1960, and Mandela and other ANC leaders were forced to go underground and then despatched to Robben Island. Their bond went back to the 1940s and remained unbreakable, despite the tensions and difficulties of communicating and consistent attempts by the regime to divide and rule, and to manipulate.

But what has always fascinated me most about OR is how he managed simultaneously to travel the world as suave-suited diplomat striding the corridors of international power, and be guerrilla Commander-in-Chief in combat fatigues in the camps of Tanzania, Zambia and Angola. Respected everywhere by everyone, by prime ministers and presidents, and by MK cadres and all in the international anti-apartheid movements.

Having myself as British Secretary of State for Northern Ireland negotiated under Prime Minister Tony Blair the peace settlement that in 2007 brought together bitter old blood enemies, fiery unionist fundamentalist Ian Paisley and former IRA Commander Martin McGuinness, to share government together, I think OR’s leadership should be a case study in conflict resolution.

Take his statement on 8 January 1986: a hard-line message broadcast and distributed clandestinely inside South Africa, to “intensify and transform the struggle into a real people’s war”, labelling Umkhonto weSizwe the “People’s Army”, and exhorting the internal resistance to greater militancy against an unreformable apartheid system.

Yet that very day at his headquarters in Lusaka he was also embarking upon discreet diplomatic and political initiatives which would ensure that the ANC was prepared (and indeed would dictate) in future, when the balance of forces determined it was time to talk with the enemy and its allies.

Far-sighted as always, and at the very height of the insurrection – not as a sign of weakness, but of confident strength – he appointed a constitution committee to start drawing up constitutional guidelines for a future South Africa. Uniquely for a liberation movement, Tambo and the ANC leadership started planning purposefully albeit very discreetly for the eventuality of negotiations and a future constitutional dispensation.

Tambo – also in discreet communications with the imprisoned Mandela – understood that every war ends with the antagonists sitting around a table. Now, judging that the balance of power was beginning to turn decisively in favour of the long-suffering disenfranchised majority, he decided that it was time to open up this new, interlinked terrain of struggle.

When we observe the Constitutional Court upholding the rule of law – including by imprisoning former President Zuma (and not many courts in the democratic world do that to former presidents) – we should remember that Tambo gave the instruction that the guidelines to be drawn up by the Constitution Committee had to ensure three things. National sovereignty – that is, the transfer of power to the dispossessed so that they could decide on their own futures – as well as a multi-party dispensation and system based on the protection of the individual rights of every South African.

This latter point was strongly made as the ANC was determined to prevent at all costs a future model based on group rights, which the regime and its allies at home and abroad favoured as a way of protecting and reproducing entrenched apartheid privileges, sometimes disguised as “minority rights” or de facto white privileges. (Tambo was laying here the foundations for South Africa’s much-lauded Bill of Rights.)

He insisted also on the ANC actively promoting the broadest possible front against apartheid so that when South Africa reached the stage of transition, the groundwork for a future national unity had been laid, expressly including in their campaigns whites, as well as progressive elements in the then Bantustan structures.

In parallel, both the jailed Nelson Mandela and Oliver Tambo tried to open up direct lines with the apartheid government, resulting in secret talks. At the same time, and aware that Margaret Thatcher was rushing to get involved, and strategically far-sighted as always, Tambo moved to assemble a solid international coalition of forces to ensure that the Constitutional Guidelines for a Democratic South Africa, adopted by the ANC in 1988, formed the basis of any future settlement.

So he was juggling these major geopolitical realignments and the unfolding internal changes, while at the same time attending to his regular job as commander-in-chief of Umkhonto weSizwe. The former maths teacher and aspirant priest turned reluctant revolutionary, who had succeeded in keeping the ANC together through nearly three harrowing decades of exile, was facing his greatest test yet.

What Pallo Jordan recently called Tambo’s “genius and energy” proved both far-sighted and decisive in isolating the regime, forcing it to release Mandela and to enter into substantive negotiations, effectively checkmating the regime politically, and engineering a universal franchise, the transfer of power and an unlikely settlement of what had long been seen as one of the world’s most intractable political conflicts.

He, communicating regularly with Mandela through secret encrypted channels, carefully combined secret overtures and “talks about talks”, with armed struggle, political mass mobilisation, underground activity and the coordination of international anti-apartheid actions to push the regime into a corner.

Thus under OR’s sophisticated leadership, the ANC outmanoeuvred opponents determined to block true democracy, as well as managing to build constructive relations with key opposite negotiators and groups. For FW de Klerk and his allies at home and abroad at the time believed that they could control the process and outmanoeuvre the liberation movements, including through security forces and “third force” violence to kill or destabilise ANC grassroots activists. But in a short four years, three centuries of white rule were formally annulled. South Africa got democracy and one of the most enlightened Constitutions in the world, which entrenched via its Bill of Rights and a Constitutional Court, the rule of law and the rights of every citizen.

For a profound insight into all this, and for what he terms “the documentary foundation stones of our democracy”, I strongly recommend André Odendaal’s forthcoming book, Dear Comrade President: How Oliver Tambo Laid the Foundations for South Africa’s Constitution (done in close collaboration with Albie Sachs and to be published by Penguin Books next year). Under Tambo’s visionary leadership, André Odendaal insists, ‘The oppressed wrested justice from history and managed to define the contours of their own destiny. Freedom was not given to them. They engineered and won it.”

Against all expectations, and the run of history, South Africans had found resolution to an historic conflict that had seemed unsolvable, fixed in granite, like Northern Ireland and Colombia were – and today still are Palestine, Kashmir, Afghanistan, Iraq, Syria, Yemen and Libya.

Most people simply take for granted the fact that Northern Ireland – leaving aside isolated attacks by small paramilitary factions and the current damaging Brexit repercussions – is now more at peace with itself than ever before, after a conflict created many centuries ago and sharpened by terrorism, brutal violence, terrible bitterness, sectarianism and prejudice.

Yet the 2007 political settlement I helped negotiate offered some guiding principles which underpinned the British government’s strategy from 1997, and which – alongside studying Oliver Tambo’s sophisticated leadership and the ANC’s strategy – could be applied to resolving conflicts elsewhere.

First, our peace-making framework in Northern Ireland did not simply address ancient Irish constitutional divisions. It tackled human rights, equality, victims and ending discrimination against Catholics in jobs and housing. It was these “bread and butter” issues – and impartial policing, prisoner releases and decommissioning of weapons – which had threatened the peace process on so many occasions. Dealing with them helped create more space for political leaders to be more flexible.

Second, people and personalities matter in politics, and building relationships of trust, even where deep differences remain, is vital. So too is understanding, rather than being judgemental about, the pressures on the protagonists from within their own community or organisation, whether these were IRA-linked political leaders in Sinn Fein or fundamentalist unionists of the Democratic Unionist Party.

Being an “honest broker” was essential in a way that had not been the case for Britain before – and has sadly not been since the Conservatives took power in 2010 and have sided consistently with unionist parties, Boris Johnson’s hard-line Brexit agenda further destabilising the peace process and political stability.

Third, it is necessary to take risks. For example, under the 1998 Good Friday Agreement releasing prisoners who had committed unspeakable atrocities. Although not easy, this was essential to show paramilitary groups that a commitment to peace brought gains which could not be achieved by violence.

Fourth, international forces need to be aligned. Tony Blair came into power in 1997 to find a strong, confident Irish government, led by Bertie Ahern, and a US President in Bill Clinton who felt a strong personal attachment to Ireland and who was influenced by the large and politically significant Irish-American community. Crucially, all three were prepared to work to a shared strategy, and each was prepared to be bold. This had never happened before and, as other parts of the world like Palestine-Israel have discovered, these alignments of leadership and circumstance do not come along often: and failure to seize the opportunity can mean condemning another generation to conflict.

Fifth, over Northern Ireland negotiations, we considered vital to avoid or resolve preconditions to dialogue. However, in South Africa’s case Tambo and the ANC manged through the Harare Declaration – and getting it endorsed by the Frontline States, the OAU, the Non-Aligned Movement, the Commonwealth and, finally, the UN General Assembly and Security Council – to outmanoeuvre and isolate the apartheid government by early on laying down preconditions which ensured genuine change, rather than more delays and more apartheid reform which had only the maintenance of white supremacy as a goal.

In the Middle East, both sides have imposed preconditions effectively blocking any dialogue from beginning, strangling the peace process at birth. In the early years of the IRA’s bloody campaign, nobody in the British government could stomach talking with republican leaders, except in surrender terms, since they were regarded as completely beyond the pale after terrorist attacks on London and Birmingham, let alone on the island of Ireland. Yet in the middle of all this bloodshed and mayhem, contact was initiated which much later on came to fruition.

It is true that entering into dialogue – especially secret dialogue – with paramilitary groups carries risks for governments. It did for British governments over Northern Ireland and it always will, but there is no alternative. As Tony Blair’s chief of staff, Jonathan Powell – who played a key role in the Good Friday peace-making programme – explains in his excellent book, Talking to Terrorists, you have to negotiate with them, offering both inducements and tough deterrents.

Sixth, it was Tony Blair’s great virtue to grip and micro-manage the Irish conflict at the highest level in a way that no British prime minister had ever done, not intermittently but continuously, whatever breakdowns, crises and anger got in the way.

By contrast, in the Middle East, efforts and initiatives have come and gone, mostly according to the US presidential cycle, and violence has returned to fill the vacuum. Fly-in, fly-out diplomacy has failed. Periodic engagement has led to false starts and dashed hopes. International forces have not been aligned and dialogue has been stunted. But Hamas and Israel cannot militarily defeat the other; they will each have to be party with each other to a negotiated solution which satisfies both Israel’s need for security and Palestinian aspirations for a viable state (if indeed that is still possible given Israel’s balkanisation of the West Bank through illegal settlements and occupying controls). And if it is no longer possible, then what?

Similar issues arose over the Taliban in Afghanistan. Instead of cultivating only Afghan forces and individuals amenable to the US from 2001, instead of occupying a country that has always rejected foreign invaders from Britain in the 1830s to the Soviets in the 1980s, surely after 9/11 the West should have negotiated a deal with the Taliban to remove al-Qaeda, instead of barging in, staying for 20 years, then fleeing ignominiously?

In Kashmir, supporting efforts to take forward negotiations between Delhi and Islamabad is the imperative. Here, perhaps the lessons are also that a seemingly irreconcilable conflict can be addressed with ingenuity. The expansion of Irish cross-border structures (and the devolution of policing and justice away from British control) was crucial to Irish republicans agreeing to share power in what remained still a devolved part of the British state they disowned and still do. If India, Pakistan and the Kashmiris themselves can agree to an entity with soft borders and greater autonomy for Kashmiris on both sides of the “line of control” between both states, then maybe progress could be made while preserving the interests and longer-term objectives of each.

But the inescapable lesson of Northern Ireland – and which Oliver Tambo intuitively understood – is that even the deepest conflicts are in the end political, and usually end in negotiation. The challenge for political leaderships embroiled in conflict is to avoid further bloodshed and devastation by moving earlier rather than later to talk, rather than fight a war neither side can win militarily.

I hope Northern Ireland will be an inspiration to those parts of the world that cannot yet even see as far as the starting point: that they too can one day enjoy the triumph of humanity in the long transition from horror to hope.

Like South Africa did so movingly in 1994 – even if it has gone from hero in those days to zero now, still in a hangover from the prodigious looting, corruption and money laundering of the Zuma presidency which so tragically betrayed the legacy of Oliver Tambo and his commitment to integrity, social justice and equal opportunities for all.

Can I end by thanking the Tambo Foundation and adding that I was both surprised and proud suddenly to be informed in 2015 that I had been awarded the Order of the Companions of OR Tambo for my “excellent contribution to the freedom Struggle”, receiving it at a moving ceremony in the presidential guesthouse that December.

It has been another singular honour to deliver this talk. A luta continua, because the struggle for freedom and justice never ends: we must continue it, not least to uphold the legacy of Oliver Tambo. DM

This is the text of Lord Peter Hain’s 2021 OR Tambo Memorial Lecture delivered on 28 October 2021.

Lord Peter Hain is a former anti-apartheid campaigner and British Cabinet Minister. His memoir, A Pretoria Boy, South Africa’s ‘Public Enemy Number One’, is published by Jonathan Ball.

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

Comments - Please login in order to comment.