SIGN OF THE TIMES

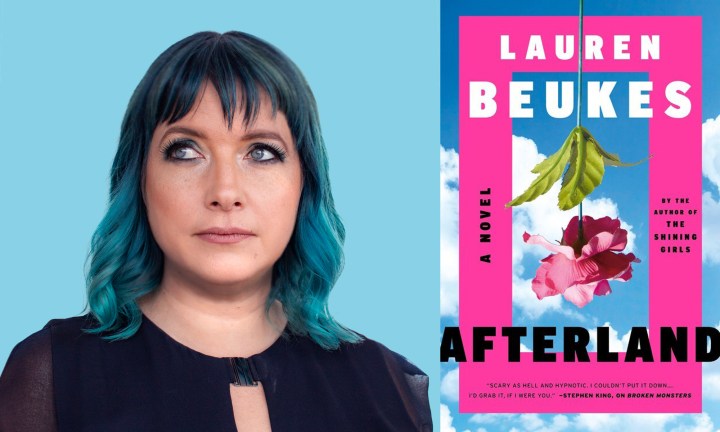

Post-pandemic bliss? Not so fast, warns author Lauren Beukes

With billionaires jet-setting into space, and ordinary folk unwilling to do their bit to stop the pandemic, author Lauren Beukes imagines a future urgently in need of salvation.

Lauren Beukes is miffed at Jeff Bezos. The bestselling Cape Town author and “outspoken feminist” isn’t necessarily cross because he and his undoubtedly enormous ego went to space in a phallus-shaped rocket ship, but because the billionaire-who-rarely-pays-tax had the gall to ask the US government to help fund his off-world adventures.

Beukes believes Bezos and his ilk could put their wealth to better use. Like using it to fix climate change. Or to address the pressing need for vaccine roll-out in Africa. Elon Musk, she says, could pay for South Africa’s entire vaccination programme without making a dent in his Dogecoin-wallet.

It affords some degree of comfort knowing that a storyteller like Beukes is thinking about these things, illuminating ways in which pivotal issues of the day intersect. Such as when she tells me – quite matter-of-factly – that the current pandemic “is very definitely a consequence of climate change”.

Which brings us to Beukes’s most recent (although now well over a year old) novel, Afterland. Like her earlier books – Moxyland, Zoo City, The Shining Girls – it hinges on a high concept, a big idea crafted to enable the reader to venture into a parallel reality where a feverishly-paced tale simultaneously prompts connection with weighty ideas. Afterland grabbed me quickly and sent me into a stupor of reading at a time – during the first hard lockdown – when concentrating on full sentences was proving very difficult.

It might have been the strange overlap between reality and fantasy. Afterland’s dystopian narrative landscape was shockingly prescient, its action happening in a just-around-the-corner future torn asunder by a pandemic. It felt like fact-made-fiction, a tale somehow inspired by current events.

Its seemingly prophetic ambitions were intoxicating. Yet, while Afterland offers a kind of premonition of a virus getting away from the scientists and sparking havoc across the globe, its connection to our current crisis was pure coincidence.

“We’d known for a long time that a major pandemic was coming,” Beukes says, “just as we know there’s a major earthquake due in California any day now.” But introducing a virus to unsettle the universe wasn’t even the crux of the matter – it was simply a device to turn the tables on the patriarchy.

“I needed a convenient way to kill off all the men. It was either a pandemic or aliens.”

Beukes was interested not in the hellscape of a world battered by a pandemic, but wanted to explore what might happen to humanity if men weren’t around.

Thus was invented the “human culgoa virus”, a contagion whose flu-like symptoms metamorphose into an aggressive prostate cancer, annihilating 99% of males – but that’s only the backstory. The real action happens in the post-pandemic aftermath. It’s essentially a brutal, action-packed chase across America, a mother ferociously protecting her prepubescent son, while extremist nuns, hardboiled female thugs, and the US’s Department of Men are among the plot’s cast of propulsive antagonists.

In Beukes’s imagination, taking men out of the picture doesn’t instantly result in some sort of Utopia, but postulating a post-male world gave rise to a kind of speculative fantasy about the many ways in which society might evolve or erode, unravel or improve.

Beukes says many of her ideas were sparked by conversations she had. “Everyone I met I asked things like, ‘Oh, you work in the mining industry, what would happen to the mines if all the men died?’ and the women I spoke to would say, ‘We’d just automate; we’ve been wanting to automate for years, but we can’t because of the unions’.”

For Beukes it was also an opportunity to reimagine human activities and social behaviours. To imagine, for example, a world in which all-male teams no longer dominate professional sports. And how would sex work? How would lust and love reorder themselves?

Such questions are poked at in Afterland, but – characteristic of Beukes’s rational, equal-opportunity understanding of human behaviour – she doesn’t shy away from exploring the likelihood that power-hungry women would step into the shoes of male oligarchs. Or, as is speculated in the book, there’d be women who’d take over their dead husbands’ crime syndicates. “Women are just as capable of terrible things, of being greedy corporate monsters and psychopaths,” says Beukes, who denounces the ridiculous assumption that feminism is about hating men, or assuming all men are evil. “I was specifically writing against that really stupid idea which is that women are incapable of evil and that women are all the good in the world.”

While there’s no female Bezos-like figure in Afterland, there’d be no reason one wouldn’t emerge.

What does assert itself rather powerfully in the book, is Beukes’s concept of home. Specifically, the idea of South Africa as home, and as the final destination for her story’s on-the-run mother-and-son. For them, getting out of America and back to Africa represents freedom.

Where South Africa and America differ, though, she says, is in how much we’ve already been through. She wants to believe that as a “mostly female” nation we would be “woken up” that much more. “It feels like it might be a more hopeful place, certainly a more contained place, and certainly a better place to raise a black son than in America,” she says.

Plus, Beukes says she can imagine that a South Africa where the aggregate of toxic masculinity has been stripped away might be a more hopeful place. “Without the gender-based violence, without men’s humiliation and the toxicity and the way they feel beaten down so that they then take it out on the people they say they love, a lot of that trauma would disappear.

“Afterland is a world where most of the men have died, and I think in South Africa in particular we have strong women-led households, particularly in more rural areas and in the townships and I think women get a lot of stuff done here, and I think we hold things together already.”

Beukes is by no means naïve to the potential for corruption to exist even if the men were all gone, of course. By way of imagining a scenario that might arise in the post-pandemic world of Afterland, she says it’s credible to imagine one of Zuma’s wives becoming president, colluding with the wrong people, and sending all our money to Dubai. “Corruption is not a male trait,” she says, “it’s a power trait and anyone is capable of possessing it.”

One imagines that, having gazed into the crystal ball to guess at what a post-pandemic world might look like, Beukes would have been well-equipped to face whatever our current crisis could throw at us. She says though that nothing could have prepared her for the isolation and loss of human connection.

Whether or not it was strategically wise to release a pandemic-themed book in the middle of a pandemic is a bit of a mystery – while the book was praised (by, among others, Stephen King, who called it a “smartly written thriller” in his review of it for The New York Times), many potential readers purposefully shied away from fiction that too closely resembled the global catastrophe that was unfolding last year. Certainly, the timing upended her planned book tours and festival appearances – activities that are vital for boosting a book’s profile and reaching the reading public.

Plus, the protracted travel bans for South Africans meant that she could not be in Chicago this year for the filming of her 2013 novel The Shining Girls which is being made into a series for Apple TV. It stars Elisabeth Moss (she of The Handmaid’s Tale) who is also producing the show alongside Leonardo DiCaprio.

And while the pandemic has infringed on her life and career – and on her love of socialising and meeting people – it has also affected her optimism somewhat. “Because I have seen how many people actually don’t care about other people,” she says. “People who can’t inconvenience themselves to wear a mask or take a vaccine, even though it’s going to help everybody else.”

And that sense of people being incapable of stepping up for the collective good bodes badly for humanity’s other fast-approaching reckoning. “We’re very bad at looking to the future,” she says. “The fact that we can’t obey the rules and take the vaccine in order to stop the pandemic now does not give me a lot of hope for climate change, which is a slow burn. And things are just going to get worse. So, I’m not feeling particularly optimistic about our ability to deal with it.”

Nor does she imagine that all our small collective endeavours – using straws or recycling – are enough to save us. “It’s the oligarchs and autocrats who are running the world who are destroying it fundamentally. It’s disgusting and awful and it’s from them that [we] need massive reform on a major level.”

Which is why, before they go joyriding in space, folks like Bezos need to take a look around and help clean up the mess they’ve helped create. DM/ ML

[hearken id=”daily-maverick/8832″]

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

Recommended reading!