Op-ed: Eswatini Uprising

In the face of pro-democracy uprising, King Mswati III reads from Selassie’s script

The bloody suppression of protest… the rise of radicalised youth… ‘development’ without political change… a leader increasingly disconnected from the real world… Drew Forrest looks at the parallels between strife-torn Eswatini and Haile Selassie’s doomed empire.

A telltale sign that an absolutist state is starting to crumble is the erosion of the monarch’s mystique.

There is a general rise in defiance of authority, including open expressions of contempt for the once-sacrosanct Supreme Leader, and growing popular insouciance towards the guns and teargas of his enforcers.

People stop being afraid.

This was clearly visible during the terminal decline of Haile Selassie’s absolute monarchy in Ethiopia. And it is a feature of the pro-democracy uprising against King Mswati of Eswatini.

An obvious parallel is that reckless youngsters, not yet imbued with the habits of subordination, are in the front rank.

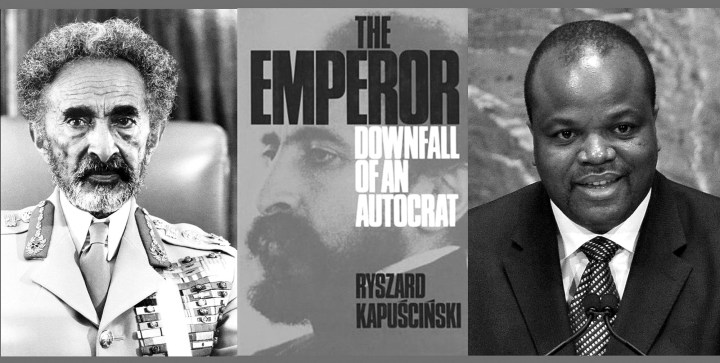

In his haunting account of Selassie’s last years, The Emperor, Polish author Ryszard Kapuściński describes the 14-year war of Ethiopia’s university students against the security forces, punctuated by “clubbing, shooting and spilling of blood”.

Five years before his fall in 1974, Selassie sent in armoured cars. “More than twenty students perished and countless others were wounded and arrested,” recounted a former courtier. “His Highness ordered that the university be closed for a year.”

(Photo: goodreads.com/Wikipedia)

The shock troops of the Swazi insurrection have been jobless young men, who make up most of the 80 protesters thought to have fallen to police bullets.

Yet, according to veteran Eswatini journalist Vuyisile Hlatshwayo, the incendiaries at the forefront of the protests now taunt the police: “You can shoot me, but you can’t kill us all!”

The upheavals have spread to the schools, which were closed indefinitely last week, and have made an appearance in rural Eswatini, historically royalty’s most secure base.

Hlatshwayo pointed to outbreaks in the rural east and south, in sleepy Siphofaneni, Lomahasha, Lavumisa and Hosea. In the latter constituency, people seem to be rallying around their MP, Bacede Mabuza, who faces terrorism charges for urging Emaswati to petition for change under the tinkhundla system.

Mabuza and another indicted MP, Mthandeni Dube, are central to an emerging cycle of state violence and popular counterviolence which tore South Africa asunder in the 1980s. Last week, police fired on students demanding their release.

In Ethiopia, rural disturbances marked a new stage in a worsening meltdown – peasants in Gojjam province “jumped on the rulers’ throats” over a sudden tax rise.

A courtier told Kapuściński that “the notables found this incomprehensible, because we had a docile, resigned, God-fearing people… and here… for no reason whatever, mutiny!”

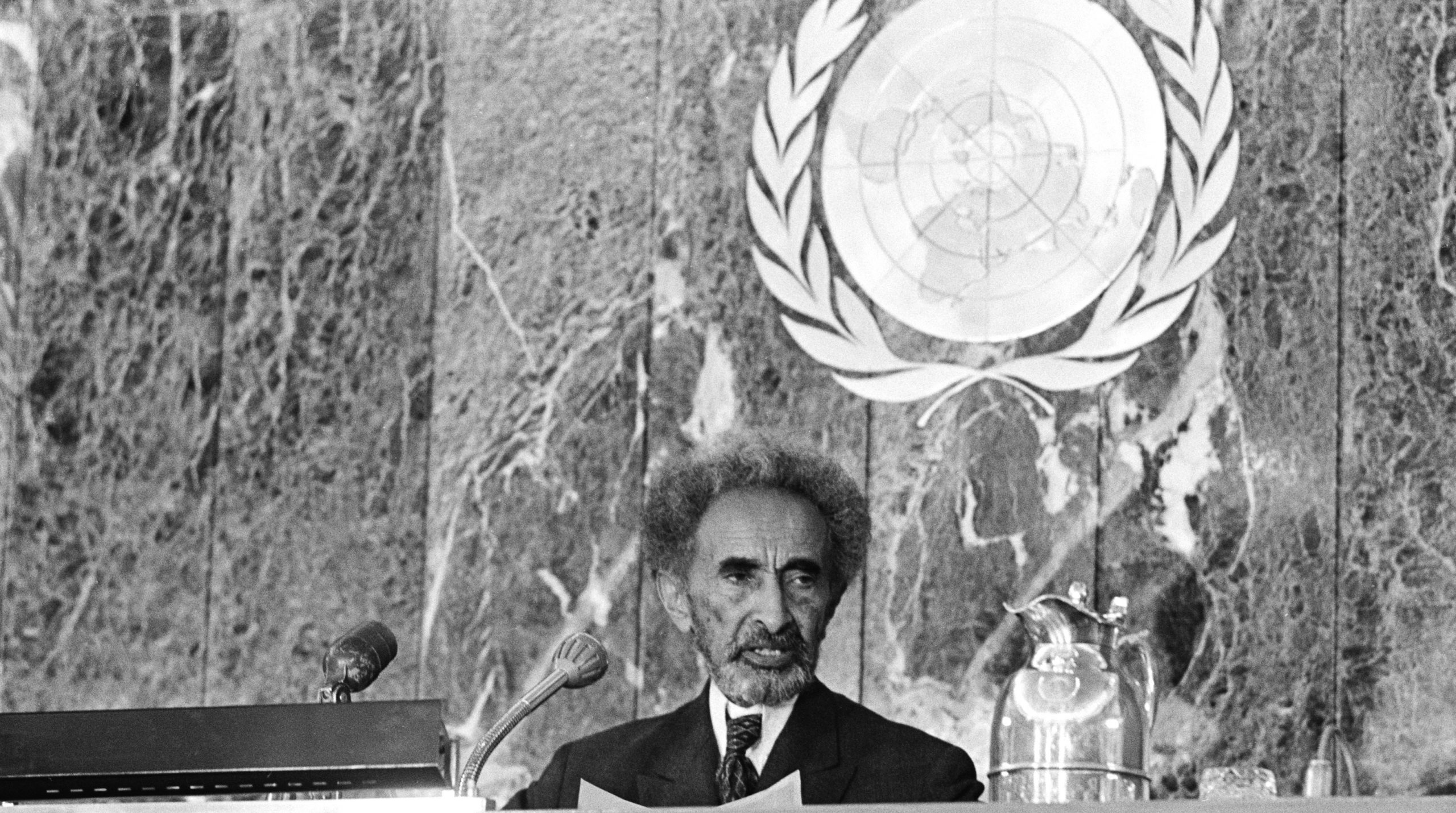

Haile Selassie (1892-1975), the Emperor of Ethiopia, opens the conference of the Organisation of African Unity in Addis Ababa on 6 February 1973. (Photo: William Lovelace/Express/Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

The tax violated what The Emperor calls “the principle of the second bag”: poor people will struggle on blindly under their ancient load, but kick fiercely against unexpected impositions.

Mswati also thinks there is “no reason whatever” to protest; in a July broadcast he insisted he would not talk to “dagga smokers and drunkards”. The order to fire on rioters allegedly descended from him.

Economic distress is a factor – the Swazi economy is in steep decline, with GDP falling 20% since 2010 to $3.9-billion. But The Emperor makes the important point that “a man does not seize an axe in defence of his wallet, but… of his dignity”.

Equal treatment and dignity are intertwined ideas. Kapuściński describes Selassie’s obscenely opulent banquet for African leaders, serenaded by Miriam Makeba, where “a great hogging, with smacking of lips and slurping” went on while the leftovers were passed to a crowd of ragged beggars behind the imperial palace.

A founder of the Organisation for African Unity, Selassie – like Mswati – prided himself on being a continental actor.

Student censure of inequality boiled over with Jonathan Dimbleby’s documentary The Unknown Famine – flighted on British TV a year before the Emperor’s overthrow – which counterpointed mass hunger in northern Ethiopia with the palace fare of imported caviar and champagne.

Brazen high life of the royals

In Eswatini, one of the world’s poorest countries, there is widespread outrage over the brazen high life of the royals, epitomised by Mswati’s purchase of 15 Rolls-Royces in late 2019 when his kingdom was short of ambulances.

After the June riots, his daughter, Princess Sikhanyiso, went on air to apologise for the royal family and promise better behaviour. Given her lowly status in traditional circles, this was greeted with cynicism.

In absolutist systems there is no contract between ruler and ruled, no idea of reciprocal duties – the people exist to serve and glorify the Leader.

“Death from hunger had existed in our Empire for hundreds of years, an everyday, natural thing,” reflected one courtier. “It never occurred to anyone to make any noise about it.”

Selassie’s knee-jerk reaction was to ban “imported slander”, much as the Swazi government has tried to restrict the flow of information by repeatedly shutting down the internet.

For the Leader the only unforgivable crime is disloyalty – meaning that the competence and probity of appointed officials is unimportant. Kapuściński writes that Selassie operated on the principle: “Let him enjoy his corruption, so long as he shows his loyalty.”

Mswati uses the government posts in his gift and veto powers over other arms of government to navigate the Byzantine politics of the palace, rewarding and protecting his relatives and acolytes.

A recent instance was the flat refusal of Lindiwe Dlamini, a royally connected former minister, to account to parliament’s powerless public accounts committee over a botched contract.

Kapuściński notes that “the King of Kings preferred bad ministers… because he liked to appear in a favourable light by contrast… Instead of one sun, fifty would be shining, and everyone would pay homage to a privately chosen planet.”

Absolute power spawns megalomaniac fantasies that no one dares contradict. Mswati’s ministers know the Mswati III International Airport and a multibillion-rand hotel and convention centre in the Ezulwini Valley – ordered by the king for guests at an African Union summit that never materialised – are useless fripperies, but nevertheless defend them as “development”.

The king has said he wants Eswatini to become a first-world country by next year. In similar fashion, three months before his arrest, Selassie announced a madcap plan for dams on the Nile.

Unencumbered by political or legal accountability, avarice balloons.

Mswati scornfully told Emaswati in his July broadcast that he owns them and the country – and it was no idle boast. He is thought to hold more than half the economy, largely through shares extracted from major corporations. His personal pile, exempt from tax, is estimated at R3-billion.

The Emperor describes the military coup plotters lifting palace carpets to find a vast store of hidden greenbacks.

No going back

Resistance is still sporadic and the king intractable, but Hlatshwayo believes there is no going back for Eswatini.

With the daily press gelded by complicit editors and a hostile judiciary, Mswati’s critics have taken with gusto to the internet.

Once inviolate, he is now incessantly decried on social media as stupid and unfit to rule, and even as an imposter who is not of the ruling Dlamini clan and whose real name is “Nketjane”.

Selassie’s courtiers complained to Kapuściński of the “mutinous rabble… reproaching, calumniating, ever more arrogantly” in the emperor’s twilight months.

As the army bulked larger as the real centre of power, he took to wearing military uniform at all times. Kapuściński describes the paradox of the Emperor almost seeking to lead the rebellion against himself.

Mswati also likes to play soldiers, presiding over military parades in scarlet, gold-braided, full-dress uniform, with presumably self-awarded medals emblazoned on his chest.

The Umbutfo Swaziland Defence Force has a R1.2-billion annual budget, the third largest in the kingdom, supplemented by R140-million for the defence department.

Constitutionally, it is non-partisan, but in practice it is Mswati’s personal bodyguard and mainstay of his power. It is to him that soldiers swear their oath of allegiance.

Drawing on the Paris Commune, Karl Marx saw the defection of the state’s dragoons as the critical moment in revolutionary change.

The Swazi army’s submission to the king has been unquestioning. But the Ethiopian precedent shows that prolonged and bloody civil strife can corrode the traditional ties of hierarchical loyalty – especially if the Leader’s extravagant vagaries raise the temperature.

Incredibly, amid the chaos of his last months, Selassie appointed himself “Grand Admiral of the Imperial Fleet”.

Also, Eswatini is a small, close-knit society where it is hard for the bully-boys of the security forces to hide.

Eswatini’s King Mswati III. (Photo: Bess Adler / Bloomberg via Getty Images)

Hlatshawayo said there was a growing trend of popular reprisals in the form of arson attacks on police houses.

At the time of the coup, Ethiopia had black Africa’s largest army; in a country of 30 million peasants, 100,000 soldiers consumed 40% of the budget.

The military staved off one coup attempt in 1960. Fourteen years later mutinous army officers themselves brought down the 3,000-year imperial dynasty, dismantling the elite piecemeal by picking off Selassie’s retainers.

His 15 palaces, one in the Ogaden Desert that he visited only once, were nationalised. (In 2004 Mswati was reported to be building a palace for each of his 11 wives. He now has 15.)

Arrested in September 1974, the Emperor was dead a year later from what the official communique described as “circulatory failure”. He was probably strangled, and his body, with cruel ignominy, stashed beneath a palace toilet. Many of his former ministers and high officials were shot.

Mswati might draw a lesson from the grisly overthrow of the Ethiopian empire – long pent-up political pressures often erupt in extreme violence.

The French writer Victor Hugo wrote that “nothing in the world… not all the armies… is as powerful as an idea whose time has come.”

In Eswatini the “idea” is still diffuse, inchoate. But its time is coming. DM/MC

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

First Mswati III, then the several nonsensical kings of South Africa, for whom the time has come. We pay hard taxes for these puppet monarchies, there only to buy votes.