OP-ED: TRAFFICKING

From Afghanistan to Mozambique’s Cabo Delgado – the implications of Taliban rule for the southern African drug trade

Afghanistan is a major supplier of drugs flowing to and through East and southern Africa. The country has long been the world’s leading source of heroin but is also increasingly producing methamphetamine, some of which in the past two years has begun to be trafficked to southern Africa.

There has been speculation as to whether the Taliban, now in control of Afghanistan, will deliver on its pledge to curb opium production in that country, or whether production will increase as Afghanistan’s economy contracts.

In Mozambique’s Cabo Delgado province, regional forces have been deployed to support the Mozambican military in combating the Al Sunnah wa Jama extremist group and have recaptured territory, but whether these developments will influence drug trafficking routes through the region is still an open question.

What is clear is that seismic political shifts are taking place along the “southern route” for drug trafficking, from Afghanistan via East and southern Africa. The fall of Afghanistan to the Taliban means that the country’s entire opium poppy crop – estimated to be as much as 80% of the world’s opium production – and its nascent methamphetamine industry are now under Taliban control.

Halfway across the world, Rwandan and Southern African Development Community (SADC) troops have been fighting the insurgency in Cabo Delgado, a key corridor in drug trafficking to and through southern Africa. Territory has been recaptured from the insurgents, including the key port town of Mocímboa da Praia, which fell under extremist control in August 2020. These developments may have a significant effect on the scale and nature of drug trafficking to East and southern Africa, although the role of extremist groups in shaping illicit economies is still often poorly understood.

How Afghanistan supplies drugs to East and southern Africa

For decades, heroin produced from poppies grown in Afghanistan has been dispatched from ports along the Makran coast of Iran and Pakistan on large ocean-faring dhows (wooden fishing vessels) and, increasingly, container vessels. These heroin cargoes are destined for trafficking networks operating in port cities along the East African coast.

Originally, these ports were waystations along the East African seaboard for onward trafficking to wealthier heroin consumer markets in Europe and the US, but this has evolved in recent years. Significant heroin consumer markets have now also emerged in cities and small towns across East and southern Africa, fed by a network of overland trafficking routes.

Originally, these ports were waystations along the East African seaboard for onward trafficking to wealthier heroin consumer markets in Europe and the US, but this has evolved in recent years. Significant heroin consumer markets have now also emerged in cities and small towns across East and southern Africa, fed by a network of overland trafficking routes.

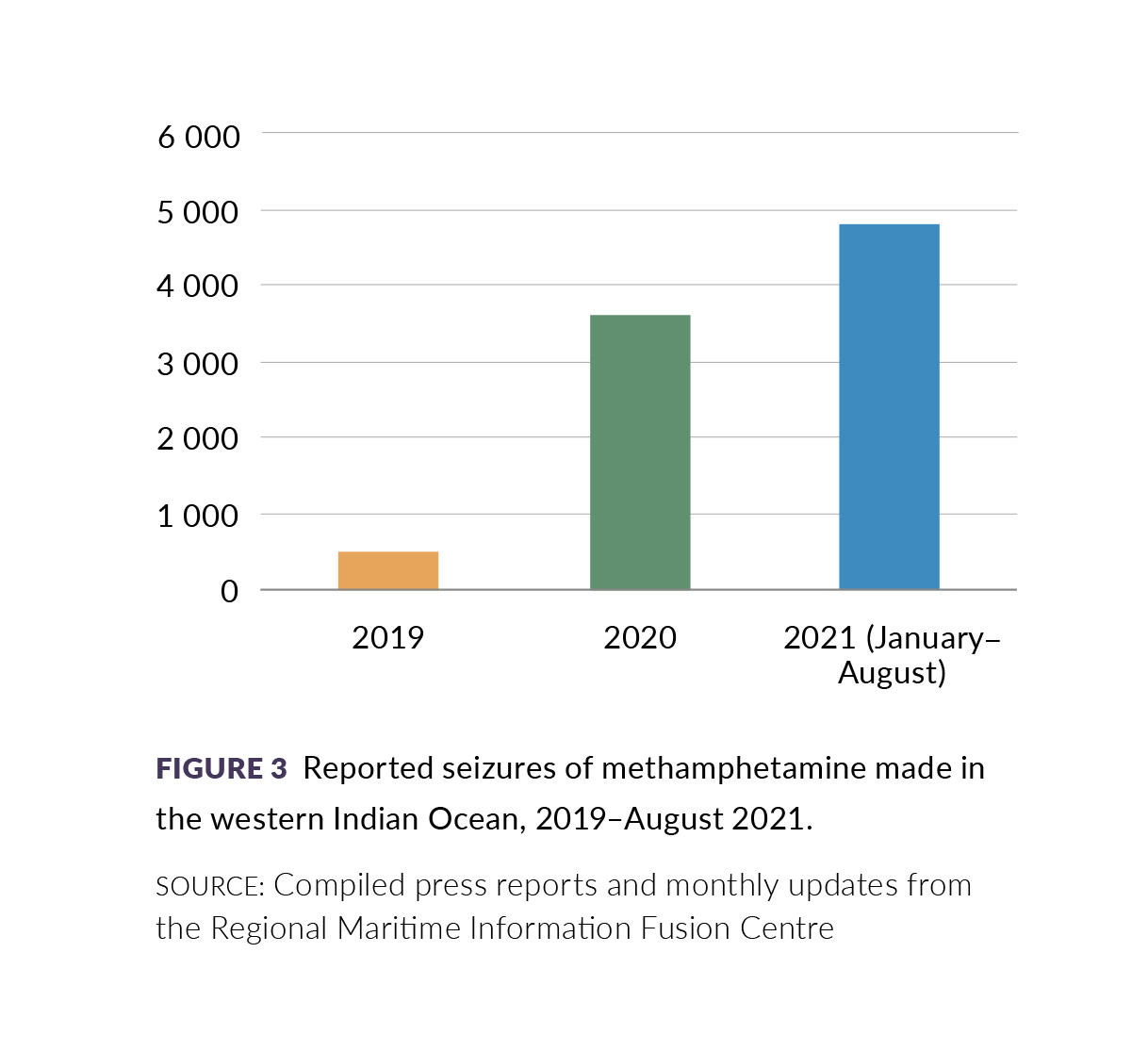

Production of meth has also boomed in Afghanistan in the past four years, thanks in part to the discovery that ephedra – a common plant growing across northern and central Afghanistan – can be used to create one of the precursor chemicals for crystal meth (known as “tik” in South Africa) simply and cheaply.

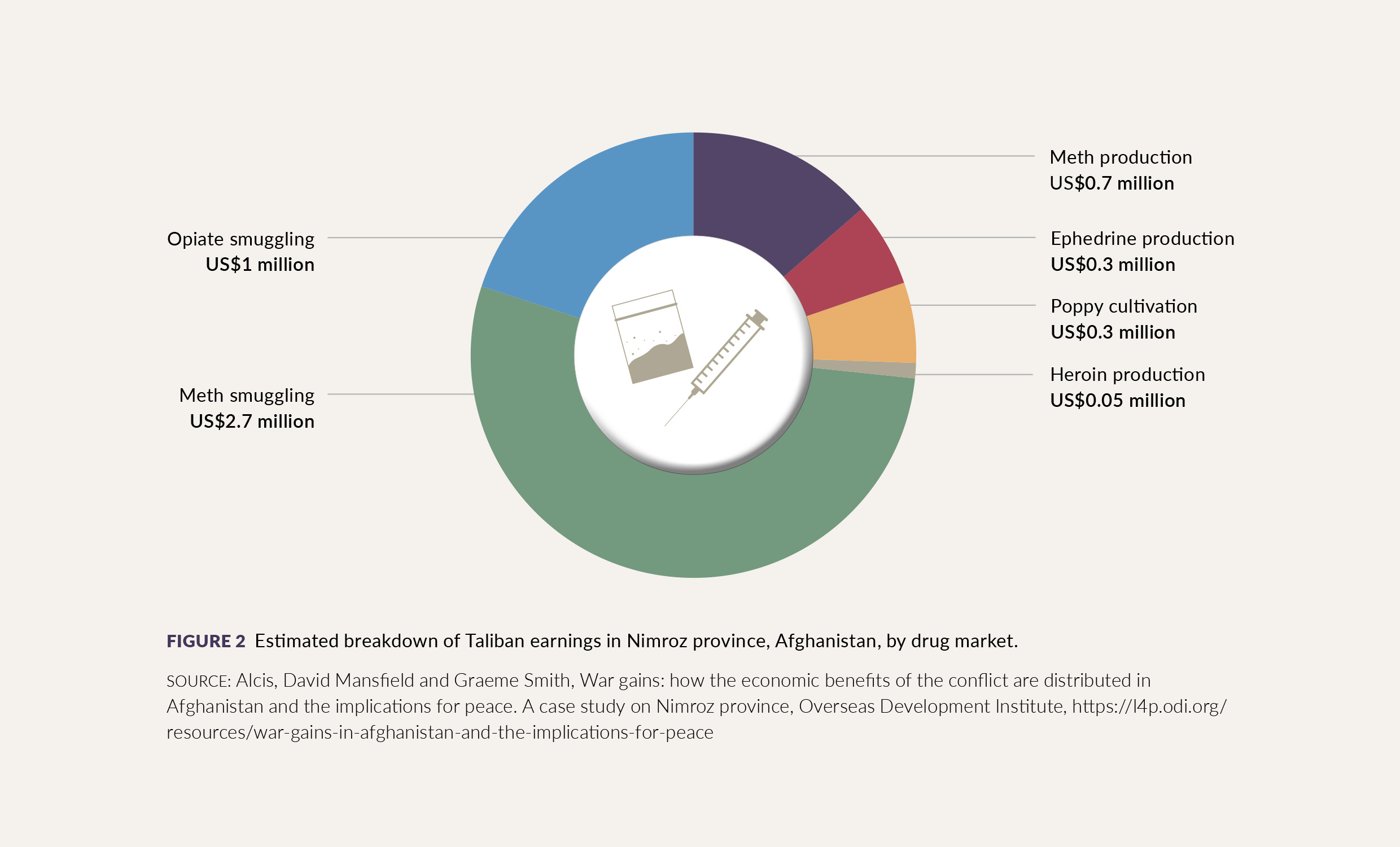

David Mansfield, a leading expert on Afghanistan’s drug industry, estimates that the Taliban derives more revenue through taxing meth production and trafficking in Nimroz province – a key drug transit region in Afghanistan – than heroin.

Recent seizures of both heroin and meth suggest that some of this new influx of Afghan meth is being trafficked into Africa, “piggybacking” on the long-established heroin trade. Our research has found that Afghan meth, arriving in the region in conjunction with the regular flows of heroin, has been available in the urban drug markets of South Africa since mid-2019.

Meth has often not been seen as a major drug being used or trafficked in Africa. Yet our research has found that crystal meth has gained a foothold in Eswatini, Lesotho, Botswana, Mozambique, Malawi, Zambia, Zimbabwe, Uganda and Kenya. South Africa is a major meth consumer market.

Data on reported drug use by drug users found that meth is the first or second-most common drug of use in most South African provinces. Tests of wastewater in two sites in the East Rand and Cape Town for residual methamphetamine in 2020 found that estimated meth use levels were among the highest reported in the world. This suggests that the number of people who use meth in South Africa, and possibly across the region, may be far higher than national drug-monitoring and health programmes currently believe.

There is a strong and growing demand for crystal meth in Africa, and Afghan meth is contributing to meeting this need.

New rulers, new anti-drug rules?

The Taliban pledged to halt drug production and smuggling in Afghanistan within days of its return to power. Yet this may be near impossible given the country’s dire economic situation. The new Taliban administration is unable to access the vast majority of Afghanistan’s foreign reserves, held overseas in countries unlikely to send funds to a sanctioned entity. Foreign aid, on which the country relies, has been suspended by many major donors.

Most significantly, the illicit drug trade is estimated to be the single-biggest economic sector in Afghanistan, providing a vital lifeline for the vast rural population. The predicted economic collapse following the Taliban takeover is expected to drive more people to plant opium poppies, rather than fewer.

Previous attempts to curb opium production have ended badly, both for the Taliban and the US and allied forces. A Taliban edict prohibiting poppy cultivation in 2000 was effective in reducing the amount of land under poppy cultivation by more than 90% for that year, but also plunged opium farming communities into poverty and was an “act of economic suicide”, weakening support for the Taliban before they were overthrown by the US and its allies in 2001, after which poppy production soared once more.

For its part, the US spent an estimated $9-billion on counternarcotics operations during the occupation, yet the results were widely acknowledged as ineffective and even counterproductive. Coercive strategies to destroy poppy fields drove up support for the Taliban in rural areas. Schemes to provide farmers with compensation payments for destroying poppy crops created perverse incentives: farmers found they could harvest the opium and then destroy the remaining plants, effectively earning double for the same crop.

A US airstrike campaign on suspected “drug labs” succeeded only in destroying simple mud-brick compounds and equipment that could easily be replaced, costing the US military far more to carry out the operations than the Taliban would ever have lost in tax revenue. Pervasive corruption in the Afghan government also undermined many counternarcotics efforts.

There is no reason Taliban promises to end drug trafficking in 2021, if enacted, would be more successful or sustainable than previous attempts. The group is also more fragmented than when they previously held power, meaning that attempts by Taliban leadership to get local commanders to give up the revenues of taxing the heroin trade, and potentially disenfranchising their local supporters, may fail.

Ultimately, the new Taliban promises to “end drug smuggling” are seen by observers as overtures to the international community, and part of a strategy to entice foreign aid back to the country and alleviate the economic crisis, rather than a commitment to counternarcotics policy. But if the Taliban do bring about a reduction in drug production in Afghanistan, this could have major knock-on effects in drug markets around the world. Vanda Felbab-Brown of the Brookings Institution believes that a shortage in the global supply of heroin from Afghanistan could spur production of synthetic opioids such as fentanyl. This could, in turn, cause a surge in overdose deaths.

In East and southern Africa, restricted heroin supplies could cause shortages and drug price rises for people who use drugs in a region where few support services are available for those undergoing withdrawal. Drugs may be increasingly bulked out with potentially harmful substances as traffickers and dealers attempt to make supplies stretch further.

Supply reduction could also reshape regional drug trafficking markets. In early 2021, the Global Initiative against Transnational Organized Crime (GI-TOC) found that an increasing number of small-time, lower-level traffickers had shifted operations from Zanzibar to establish a foothold in northern Mozambique. In the event of significant price hikes for wholesale heroin and meth, these smaller-scale traffickers may be squeezed out of the market, leaving the northern Mozambican trafficking route in the hands of only the wealthier, more established traffickers. These individuals are most often members of the local business elite and benefit from corrupt protection from prosecution.

An illicit sideline, not a major revenue stream

Far from reducing drug production, other observers of the Afghanistan crisis have made dire predictions that the Taliban will in fact increase drug production to flood Western nations with heroin. However, experts on Afghan political economy have argued that such claims are unrealistic and misunderstand how the Taliban engage with the drug trade.

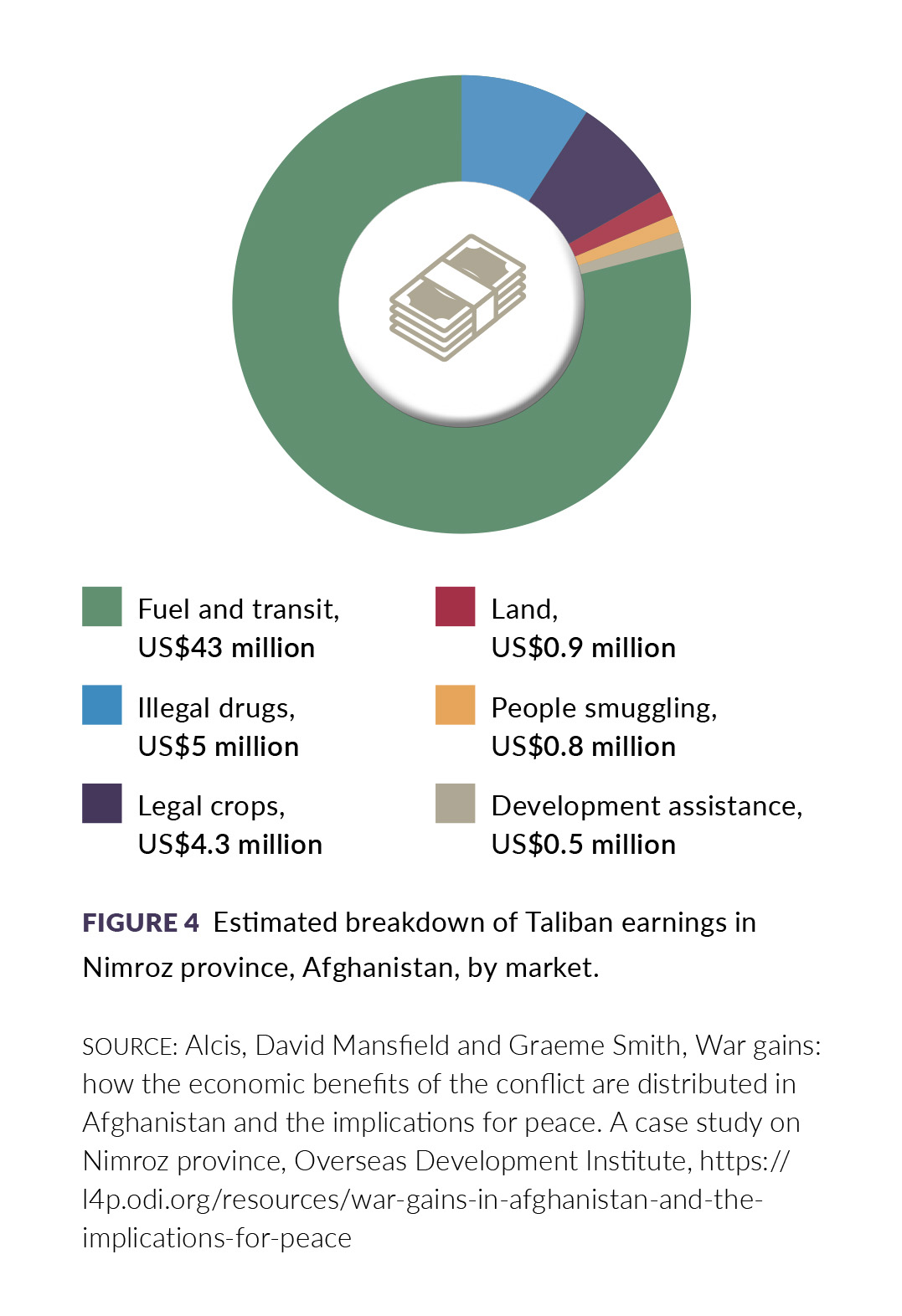

Far from being – as some have described – a “drug cartel”, the Taliban, like members of the former Afghan government, benefit from the drug trade by taxing production sites and trafficking routes, rather than actively participating in the market and controlling rates of production. The analysis of Taliban taxation of the informal and illicit economy in Nimroz province found that they derive far more income from taxing the cross-border transit of legal goods such as food, fuel and cigarettes than illegal goods such as drugs. Estimates of how much money the Taliban derive from taxing drugs are often vastly overstated.

However, if heroin and meth production do significantly rise following the Taliban takeover (which may occur because of the collapse of the legal economy, rather than active Taliban policy to promote the trade), East and southern Africa may see drug prices decrease as a surfeit of supply reaches African shores. To return to the example of northern Mozambique, the trend of “diversification” of the trade observed in early 2021 could continue, as more small-scale traffickers would continue to be able to finance small drug shipments and gain a foothold in an expanding market.

A trafficking-conflict nexus in Cabo Delgado?

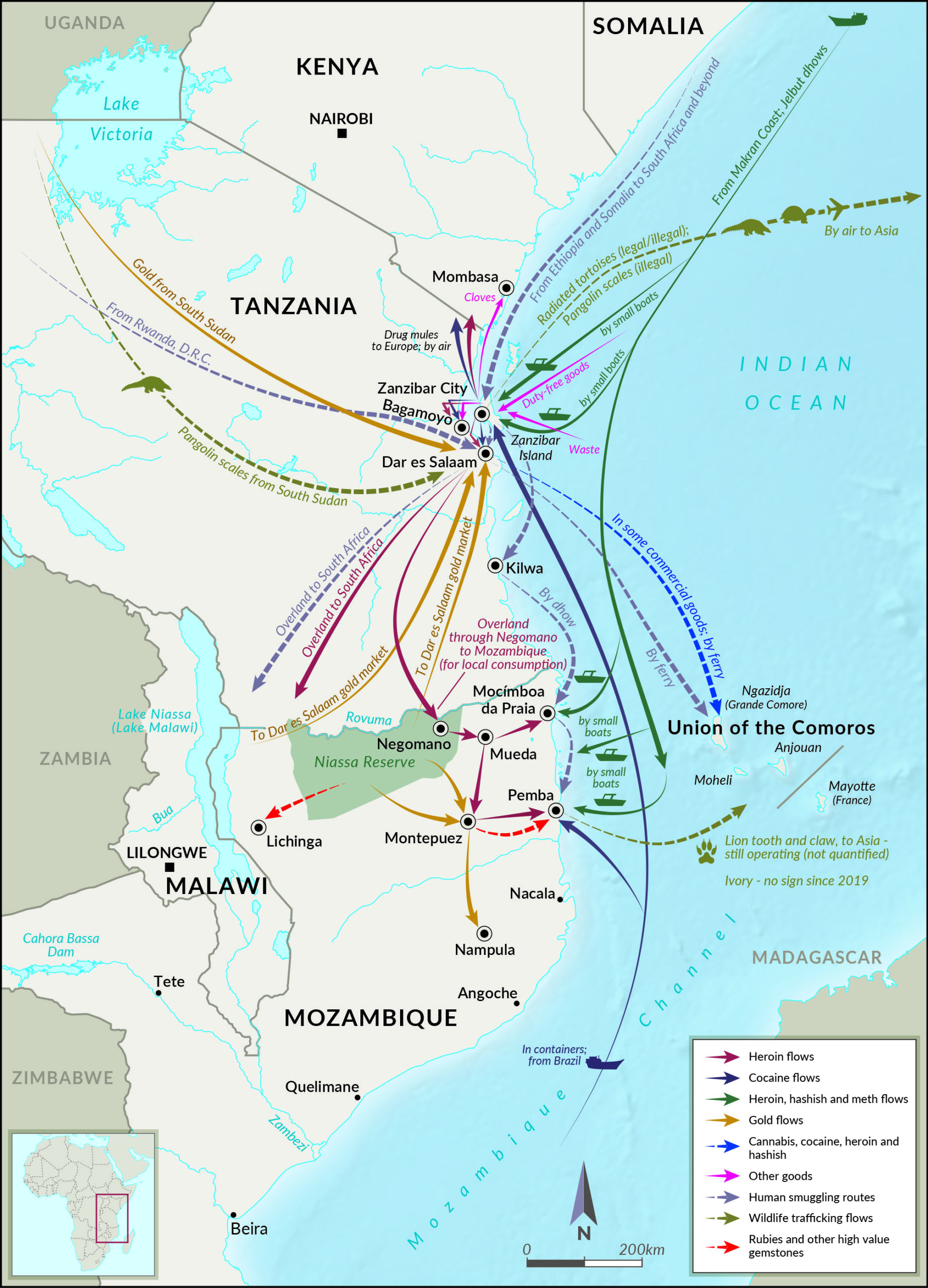

Since late 2017, the Islamist group variously known as Al Sunnah wa Jama (ASWJ), al-Shabaab (though not affiliated to the Somali group of the same name) or, locally, as the “machababos”, has been staging attacks in Cabo Delgado. The insurgency has reshaped the major trafficking routes that previously traversed the northern part of this province, including long-standing illicit flows of heroin, rubies, gold, timber, wildlife and migrant smuggling.

Our research in northern Mozambique in January and February 2021 found that, rather than these trafficking routes becoming a major source of income for the ASWJ, the risks of the violence and the logistical challenges of moving contraband through a heavily militarised area caused trafficking networks to shift south to new and safer routes. Other researchers who have conducted recent fieldwork around the conflict in Cabo Delgado have also corroborated these findings.

For drugs, this has meant that drop-offs of heroin and meth from dhows previously made onto beaches in northern Cabo Delgado – around Mocímboa da Praia, Quissanga and Pemba – began to be made at points further south. This still included Pemba (which remained out of insurgent control), but also the relatively safer coast of Nampula district (Nacala and Angoche). Some traffickers known to the GI-TOC who were previously based in Mocímboa da Praia moved operations to Nacala.

Illicit flows through northern Mozambique as of February 2021. (Source: Observatory of Illicit Economies in East and Southern Africa, Risk Bulletin – Issue 17, Global Initiative Against Transnational Organized Crime, March–April 2021)

Much like Afghanistan, the balance of the conflict has shifted rapidly. Since August, Rwandan and SADC forces have been deployed to support the Mozambican military in combating the insurgency and have recaptured territory and overrun insurgent bases, including the town of Mocímboa da Praia. As well as Rwanda and SADC forces, other nations such as the US and Portugal are providing support and specialised training to the Mozambican military.

While former trafficking hotspots – such as Mocímboa da Praia and the surrounding coastline – have now come back under government control, our finding is that the shift in the conflict has, as yet, had no impact on drug trafficking routes. Traffickers who moved south to avoid the ASWJ territory and the conflict zone have, so far, remained, and heroin and meth shipments by dhow and container are continuing to reach the more southerly ports.

João Feijó, a researcher with the Observatório do Meio Rural (observatory of the rural environment), who recently published a major study on the insurgency drawn from interviews with women who had been taken hostage by the group, agreed with this assessment.

However, this does not preclude drug trafficking returning to northern Cabo Delgado in future. Many of the same individuals identified as involved in drug trafficking in the area by previous GI-TOC research remain economically active in northern Mozambique. Drug trafficking in Mocímboa da Praia, before the advent of the insurgency, was closely intertwined with the local economic and political elite. If these same elites return to a more peaceable Mocímboa da Praia in future, the area could once again become a major trafficking conduit.

From Afghanistan to Mozambique: Misconceptions about the drug economy

In Afghanistan, the connections between insurgents and the drug trade have often been poorly understood or overestimated. This led to wasteful and damaging policy decisions. There is a risk that the same thing could happen in Mozambique now that Cabo Delgado has become a theatre for international military interventions.

For example, speaking earlier this year, John Godfrey, a US counterterrorism envoy, referred to “a nexus between terrorism finance and narcotics trafficking in Mozambique that’s particularly problematic” in relation to the US designation of the ASWJ as a foreign terrorist organisation. Yet our research – and any other publicly available research – has found no evidence of a significant relationship between the ASWJ and drug trafficking.

Speaking at a conference on the militarisation of Cabo Delgado, Adriano Nuvunga, director of the Mozambican think tank the Centro para Democracia e Desenvolvimento (Centre for Democracy and Development), warned that deployments of foreign forces – such as those now active in Cabo Delgado – may “gain a life of their own” over time and engage beyond their initial mandate. This was seen in Afghanistan where US and allied forces extended beyond their initial mandate (of preventing the country from being a haven for terrorists) into other issues including counternarcotics.

The drivers of trafficking through Cabo Delgado include, in broad terms, endemic corruption, poor governance and security, widespread poverty and a lack of legitimate economic opportunities for large sections of the population. These are the same factors that have stoked disenfranchisement and anger at the Mozambican government, and which created the conditions for the insurgency and continue to drive it. A militarised response to drug trafficking does not change these underlying drivers, and may only exacerbate them.

In this context, the repeated failures to curb the drug market in Afghanistan could be a valuable lesson. DM

This article appears in the Global Initiative against Transnational Organized Crime’s monthly East and Southern Africa Risk Bulletin. The Global Initiative is a network of more than 500 experts on organised crime drawn from law enforcement, academia, conservation, technology, media, the private sector and development agencies. It publishes research and analysis on emerging criminal threats and works to develop innovative strategies to counter organised crime globally. To receive monthly Risk Bulletin updates, please sign up here.

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

Comments - Please login in order to comment.