GIRAFFE JOURNEYS

Of Giraffes and Humming in the AfroAsian Seas: Ari Sitas in conversation with Jade Gibson

Dr Jade Gibson, historical anthropologist, artist and writer speaks to Ari Sitas about the ‘Giraffe Humming’ project which will premiere at the end of October in Cape Town.

For decades Ari Sitas has made a point, way beyond his academic standing, of challenging the way we appreciate words, poetry, lyrics, and how to blend all that with exciting sounds from our AfroAsian worlds. Since the late 1970s his work has always been radical, demanding and untiring.

As he was getting traction with one of his brainchildren, the Insurrections Ensemble, he set off on another mad journey of historical musicology – about what existed before the 1500s around the AfroAsian seas. And before we had listened to some of that properly he was working on reconstructing the “degenerate” music of the 1930s in Europe with his friend, pianist George Mari, as well as reconstructing a Caribbean slant on antifascism through excavating peculiar moments involving the Cesaires and Nazism’s refugees. This work has been broadcast by Chimurenga’s Pan African Space Station, and the Indian Cultural Forum.

And then, we hear that in Delhi he is considered one of the initiators of post-dramatic drama, with a controversial production called Dark Things, directed by Anuradha Kapur, which was based on his extraordinary book, Notes for an Oratorio on Small Things that Fall.

Now he and his friends have finished the libretto for the journey of three giraffes, out of Malindi (in modern-day Kenya) to China via Bengal, in the year 1414 and he is busy with its production. To describe all this and name whom he has involved in this journey will take all the space allotted to us.

***

Jade Gibson: In this production by the AfroAsia Ensemble, the story is of a giraffe journeying to China, via Bengal in India and originally from Malindi in East Africa. What was the appeal of focusing on a giraffe for this creative endeavour, and the inspiration? Do you focus on one giraffe or many, or is this a metaphorical take on the journey of the giraffe? How does the image and/or story of the giraffe relate to the production, and how do you represent it? Is this many stories or one story that is being told?

Ari Sitas: For me time has always been longer than rope.

We had done the movement of people and the stories of slavery. Two forthcoming pieces of work will complete our commitment to deal with a slaving past which is not just about the Middle Passage. We are also doing a bi-communal and tri-continental take on Othello in Cyprus. We called it Othello’s Wild Years and it is the prelude to the famous bard’s one. And we are also dealing with Gabriel, an Ethiopian Jew abducted into slavery, failing to find freedom anywhere despite multiple conversions, to be sorted out by the Inquisition in Goa as an impostor to Christianity.

We dealt with the voices of escaped slave-women from Baghdad last year in A Sea-Drift of Songs. It was time to deal with our violence against nature – a very easy project, you see – look giraffe, catch giraffe, fold giraffe in a box, dispatch it to China. Simple. Now make some music!

Slow it down. Take each part seriously. Get a group of historians and writers together to explore facets of it: Tansen Sen, Dilip Menon, the great writers, Yvonne Adhiambo Owuor from Kenya and Alvin Pang from Singapore.

Listen to them carefully, start researching who catches, who boxes, who transports, who feeds, what do they feed them and the like. Back into the world of power, classes, servitude. The giraffes were destined as a gift to the sheiks of Bengal. But at that moment, Zheng He’s fleet arrives and he says, “What’s that? I want one of THAT for my emperor.” Three hundred ships with 28,000 men (and some women), half of whom are armed to perfection, are a problem. You get generous – you gift a giraffe, and its handler too.

We have always argued that there were incredible paths and interconnections in the world before European foraging. Another world was possible. But we are not there to idealise it, some of it was brutal and violent. But its music has to be recovered, it was filled too with a very fine music.

Professor Sitas. (Photo: National Institute for the Humanities and Social Sciences)

How is the music and text inspired by the story, and how does it expand upon it? What else in this performance will be explored in relation to a precolonial world history? What bigger story is that of the giraffe telling?

We dealt with the obvious sources, sources you know very well, Jade. But our research alerted us to the “sounds-like” of a range of sonic landscapes: both the high class and caste and low class and caste music of the AfroAsian seas. We had musical friends in East Africa and India who could suggest wonders, but China was a harder challenge.

My initial hunch was to invite a great composer like Bright Sheng to take control because his work on Chinese forms was exemplary. But my long-time Insurrections collaborator and friend, Sumangala Damodaran, took over and divvied up the tasks and chose the instruments. The Chinese artist friend who helped us with the bird-drawings of the Sea-drift of Songs project last year contacted friends of friends and they put us in touch with two tremendous composers and performers, Ying Li, a professor of music and an expert of the erhu and Daiguo Li, a master of the pipa and of the Chinese zithers.

As the crews of outbound dhows would have been East African, we made sure Ngoma and call-and-response pieces called amba in Swahili and in Coastland India would provide a rhythmic undertow.

And then, I had to sit down in wonder. I listened to giraffes humming, which they do only at night. It was deep and tritonic. So, I called on Brydon Bolton, and asked him to construct/improvise something like that on his double bass with his bow on the low registers. It worked. From that we will have the great string players to flesh out soundscapes, Selamawit Aragaw from Ethiopia on her violin, Ahsan Ali with his sarangi from India and Ying Li with her erhu from China.

We did not want, oh this is Indian, oh this is Chinese, but wanted the ensemble to be everything.

What other knowledge is drawn upon and what does it contribute to the knowledge of AfroAsian connections in general?

So, the story of the giraffe was documented and we ran into it following Zheng He’s forays into our seas – we read his scribe, Ma Huan’s accounts, and we followed research undertaken in Gujarat, in Malabar, and so on. We listened to musicians now who claim ancient lineages, we note it down, learn what they play. We talk to a lot of historians. There are the canonical and dated texts from Yared’s time in Addis Ababa, there is Al-Farabi’s Grand Book of Music of the 9th century, there is Sarangadeva’s text from the 13th century from India, and lots of Chinese texts.

I called what I do fictive or imaginative realism: although some of this is fictional, each sentence can be footnoted!

Tell me how the group began, and what they have worked on so far?

As I indicated, there is a core around Sumangala Damodaran and I since 2010. This is an AfroIndian core: Sazi Dlamini, Reza Khota, Brydon Bolton, Tlale Makhene, Tina Schouw, from this side, Ahsan Ali, Pritam Ghosal and by now increasingly Kathyayini Dash and Mark Aranha from that side.

To this we add new friends. This time from Tanzania and Zanzibar, Ethiopia and China. It is all about Zooms and working online. A week before the performance we will gather and put the event together. The main composers this time around argued that they could not handle English lyrics. Give us Urdu, Hindi, Bangla, Malayalam, Mandarin, Swahili or isiZulu, they said. A songstress like Tina Schouw was unavailable, other friends were Covid-struck, so we were stuck…. Enter George Mari who had studied composition and churned out plenty Anglo-tinged tunes in Durban.

The previous productions by the AfroAsia Ensemble have been visually as well as musically evocative. What visual and musical surprises might you have in store this time? What is exciting about this project? How might the audience come away from this production thinking differently about Africa’s and Asia’s past, and how is this relevant to the decolonial present? Who will it appeal to?

Now giraffes, elephants and rhinos have had a wonderful innings as lifelike puppets by the Handspring Puppet Company and also by the kinetic object projects of the Centre for Humanities Research at UWC. Kentridge too has paid them great homage with charcoal and fine lines. Their perfection in poise and movement was always something to behold. We did not want that approach for this project though.

Purav Goswami, with whom I had worked in Delhi on Dark Things, was convinced that we could tell the story on a table by pushing around all kinds of sculpted objects. It has become more complicated now because it will involve two ladders and two tabular platforms and small puppets. Enter Jill Joubert and her wooden masterpieces; enter others, like street culture-influenced artist Breeze Yoko, and maker of complex menageries and assemblages Stephané Conradie; enter Benjamin Haskins ready to animate anything, so at least the visual would be taken care of, so all we had to worry about was a script and, you guessed right: the music.

We avoid the liberal sop I hope: giraffe in tears speaking in English about her clan’s woes. We are a bit more subtle than that… I do hope we are!

The giraffe hums, but it so happens that the Giraffe Keeper, to please his Sheik and Master, claims to understand the language and has the ability to translate. Can he? We will never know, but there will be issues raised.

To be even more direct, the music will tell you what is being indicated. Last year, you had Grasella Luigi in Amharic, Lungiswa Plaatjies in isiXhosa, Kathya in a number of Indian languages, singing about their condition. Everyone in the audience could sense what they were trying to say; there is an emotional swoop in the tonal that does solid and meaning-infused work.

A Giraffe puppet contemplating its future. (Image: Benjamin Haskins)

What music are you dealing with these days?

All music.

The problem is about who chooses the strange music you should be listening to. I follow a few magazines here and there and by now most people will have stuff online. The “have you heard so and so” is a constant, the collapse of Eurocentrism has not made things easier. BBC has a few good world music programmes, I don’t know. Otherwise, you have to cultivate a group of “amaReliables” and expect that a friend you correspond with from Mexico knows something about local music.

We were all raised with the importance of the West’s culture, but all of us, to the last one of us, were surrounded by other tonalities. We have to learn to cut Shakespeare loose from imperialism, and appreciate the West’s good stuff as a result of a unique struggle over there. I agree with Jordi Savall, the Spanish medievalist and maestro, that the future of music depends on new forms of dialogue that demean no one.

What exciting work is coming next from the AfroAsia Ensemble?

These are difficult questions for all musicians. The danger is a return of neo-feudalism: the grand personae that grant you a commission. Or the music industry that has ways of enhancing its hold on the money. Or bribes for the DJ. Uploading and downloading has made Jeff Bezos and people like that very rich. Without that object, the album, we are a bit lost.

In terms of the need for speed or effervescence, of quick showy statements, well, good luck to all of us. That is why we do not have a ring-tone hit. And we do not do hit slogans either. Since Storming (our loose adaptation of Cesaire’s Tempest) we are experimenting with long movements and we don’t break for refreshments any more. We do believe that you have to drag your audience in and avoid the need to get to a flourish every three minutes.

A Ming-era painting of a tribute giraffe.

(Photo: Supplied)

In terms of the AfroAsia Ensemble, we tried our hand in film-streaming… never as satisfactory, but gives an idea of what the event was. We made two documentaries, one by Thabo Bopape in Cape Town, one by Abhishek Dutta in Delhi, you know, it’s very difficult. I loved the Music of Strangers, the doccie about the Silk Road Ensemble.

You would need a new concept that thinks film first and then do a Covid-plagued Non-Travelling Players, slowly, sonorously, so the meanings of the dialogue get amplified. But then, that is very expensive.

We had funds this time, unlike the Insurrection Ensemble projects, where they are about really cutting corners. Let’s be frank: if it was not for a few awards here and there, and funds from festivals it would have ceased to exist as an ensemble. Historical work has some funding for this year, thanks to an AW Mellon Foundation’s generous grant. There will be no more money from them next year, so this Giraffe project has to impress some other donors or the journey will be over.

It is very hard to predict, because the rule is that a core member names her or his successor if unavailable for a project. In terms of non-core members and guests the collective decides – so there is an internal mechanism for renewal. So, having been present in all its incarnations, I would have to think hard who should take over from me. There are quite a few poets who could easily be identified, but whether they can do lyrics is another story, or whether they are humble enough to see their stuff torn asunder by musos, is yet another issue!

It is not just about making beautiful music, it is about that special relationship between sound and word, and it is about using one of the most potent ways of generating human feeling, ie, music, to create a dialogue between continents. India-South Africa was accidental. Now, we are working with Chinese and Ethiopian musicians; how do you manage the substantive tension between the “traditions” and how do you learn to listen to each other?

We have by now a transnational family of composers and performers who do a project like this out of love, and try and earn their real money elsewhere. DM/MC/ML

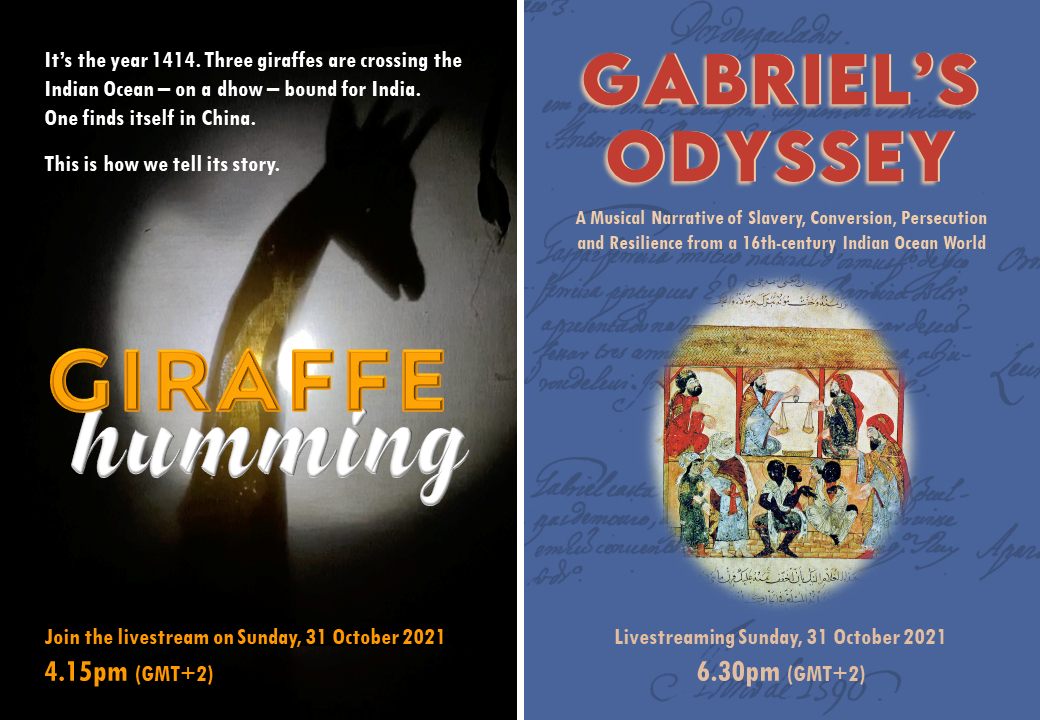

Performance posters. Image: Supplied

The performances will be streamed. To watch the show, on 30 October, click here; on 31 October, click here.

Dr Jade Gibson is a visual anthropologist (PhD, MA) with a medical (BSc hons) and visual arts (BA hons) background, artist and author of prize-listed novel Glowfly Dance. She is a passionately interdisciplinary theoretician who enjoys incorporating creative practice in addressing social issues. She has worked in research, lecturing and community projects in Africa, the UK, and South Pacific, including the Re-Centring AfroAsia: Musical and Human Migrations in the Precolonial Period 700–1500 AD Project.

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

ARI SITAS YOU ARE AMAZING