RACE IN AMERICA

Olivier with a twist: Composer Bright Sheng and the mysteries of race in America

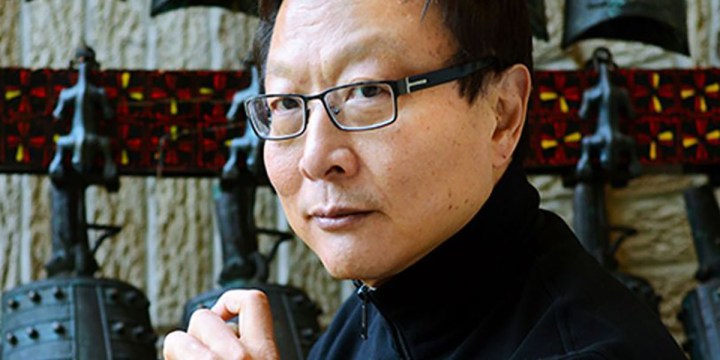

Composer and professor of music Bright Sheng found himself right in the centre of conflicts over race and identity — and blackface — when he tried to teach the mysteries of turning Shakespearean drama into opera.

It is not often that a screening of a classic film for a university undergraduate classroom gets breathless coverage in major newspapers, with increasingly furious commentary from people watching the ensuing controversy.

At first blush, such an activity would certainly have seemed to be innocent enough. In this case, a session of renowned composer and music professor Bright Sheng’s music composition class at the University of Michigan was supposed to be an exploration of the complexities of taking a straight dramatic work — a stage play — and turning it into a powerful opera.

Sheng carries a CV that includes one of only a small number of contemporary operas including The Dream of the Red Chamber, (listen to discussion on the opera here and a workshop performance of the work here) that have been performed around the world. His output also includes a roster of other compositions that get appreciative hearings in many concert halls, along with other honours and awards (including one of those MacArthur “genius” awards) that could make accomplished people very envious.

It should also be recalled that prior to coming to America, while a student in China amid the country’s Cultural Revolution, he was expelled from his university, then forcibly rusticated and humiliated by those wreaking chaos across the country for years.

To bring his lesson plan to the fore, Sheng paired William Shakespeare’s Othello and Giuseppe Verdi’s Otello, the opera built upon Shakespeare’s play. Both are supremely dramatic works, and for a long, long time, critics have seen both works as having come along when both men were at the top of their respective games. A lesson like this would seem a particularly obvious, instructive one for would-be composers.

To carry out this lesson, Sheng selected the 1965 cinematic classic version of Othello, starring Sir Laurence Olivier, an actor at the peak of his dramatic power. However, it turned out there was a fly in this particular ointment. Olivier and the film’s director, Stuart Burge, had decided Olivier would play Shakespeare’s tragic Moor sheathed in a rather thick coating of some very dark makeup. Very thick, and very dark.

Seen now, it is almost eerie looking through our contemporary eyes. The makeup in the film was clearly based on the rather obvious fact Olivier’s character is clearly from Africa (something Olivier clearly was not), and because it was to be filmed in colour, the decision was that such makeup would add a level of verisimilitude to the proceedings.

Of course, there are other cinematic versions of the play, such as Laurence Fishburne’s portrayal, and there are certainly video recordings of various live stage productions from around the world, but Laurence Olivier is, after all, Olivier.

Come to think of it, there might even be a semi-bootleg copy of the astonishing Market Theatre production of the same play in Johannesburg in 1987, starring John Kani and Joanna Weinberg. That production left its South African audiences either stunned into some kind of silence or driven towards increasing outrage by its sheer physicality.

As the reporting on the recent fracas at the University of Michigan described it, in our current age of social media, as smartphones are used during classes as well as in the time between them, the electronic rumbling over Sheng’s choice of the cinematic scene-setter began building almost from the moment Olivier’s Othello strode on to the set of the film. In blackface.

To be fair, Sheng seems to have assumed his juxtaposition of play and opera would be about his course’s contents and how to shape drama to opera, rather than a statement on contemporary American life and racial angers, fears and failings. Nonetheless, this moment of cinematic anxiety triggered debate about a whole clutch of racial issues.

It juxtaposed a belief that one important task of a university is to provide surcease for students confronting such issues — the creation of a so-called “safe space” (or the lack of it) in the words of one student speaking angrily about Prof Sheng’s class — rather than being the way and the venue to explore and debate dangerous ideas. There is also, however, the vexatious issue of “blackface”, but that we’ll address a little further along.

An author who in his life has become intimately familiar with censorship, being sanctioned by authorities and even being driven into enforced periods of public silence, Salman Rushdie, argues that the role of the university is that it “… is the place where young people should be challenged every day, where everything they know should be put into question, so that they can think and learn and grow up. And the idea that they should be protected from ideas that they might not like is the opposite of what a university should be”.

Nevertheless, the controversy over Olivier’s Othello in Sheng’s class quickly leapt from student social media to campus newspaper to The New York Times, especially since it seemed to be following the larger arc of debate about racial mores on campuses — and in other institutions.

Frank Finlay, left, and Laurence Olivier in ‘Othello’ (1965). (Photo: Getty Images / Smith Collection)

As the Times reported, “students said they sat in stunned silence as Olivier appeared onscreen in thickly painted blackface makeup. Even before class ended 90 minutes later, group chat messages were flying, along with at least one email of complaint to the department reporting that many students were ‘incredibly offended both by this video and by the lack of explanation as to why this was selected for our class’.

“Within hours, Professor Sheng had sent a terse email issuing the first of what would be two apologies. Then, after weeks of emails, open letters and cancelled classes, it was announced on Oct. 1 that Professor Sheng — a two-time Pulitzer finalist and winner of a MacArthur ‘genius’ grant — was voluntarily stepping back from the class entirely, in order to allow for a ‘positive learning environment’.”

Weeks later, after the university’s decision to distance him from class, and then a reversal of that original decision, Sheng was finally back in front of classes, but sans Olivier and Othello, it seems.

In Sheng’s second apology, he wrote, “of course, facing criticism for my misjudgement as a professor here is nothing like the experience that many Chinese professors faced during the Cultural Revolution. But it feels uncomfortable that we live in an era where people can attempt to destroy the career and reputation of others with public denunciation. I am not too old to learn, and this mistake has taught me much.”

The Times added, “to some observers, it’s a case of campus ‘cancel culture’ run amok, with overzealous students refusing to accept an apology — with the added twist that the Chinese-born Professor Sheng was a survivor of the Cultural Revolution, during which the Red Guards had seized the family piano. To others, the incident is symbolic of an arrogant academic and artistic old guard and of the deeply embedded anti-black racism in classical music, a field that has been slow to abandon performance traditions featuring blackface and other racialised makeup”.

Rightwing publications like the National Review naturally took up the cudgels as well, insisting Sheng’s mortification and victimhood had become just another example of America’s cancel culture gone mad. Sheng’s humiliation, thus, was another grievous example of a famous person who didn’t hew to the strictures of wokeness as those who enforced them wanted them to be.

By contrast, a body named the International Youth and Students for Social Equality saw things differently — the attack on Sheng came because of a flawed understanding of race and class on the part of his critics. They argued, “the actions taken against Professor Sheng, a world-renowned scholar, may well rank as the most shameful episode in the university’s history. It exposes the extent to which the unrelenting promotion of racialist ideologies — fraudulently legitimised with pretentious postmodernist jargon — has created a thoroughly toxic environment on university campuses.

“Any serious examination of Shakespeare’s play and the career of one of the 20th century’s greatest actors demolishes the charges of racism levelled against Olivier and the 1965 production. Comparisons to the racist depictions of African Americans in blackface are ignorant. The denunciation of Olivier’s performance is particularly preposterous in that the actor was attempting to take on the timid, semi-racist approaches to the Othello character that had prevailed for a century and a half.”

But the awkward question of “blackface” remains, especially as it has been a part of the national texture for a long time. Back in the early 1960s, the traditional Philadelphia New Year’s Parade had always featured competitive bands, the Mummers, who spent the year creating elaborate costumes and practising intricate marching routines. (This was something not entirely different from the traditional Cape Town Minstrel Carnival.) The Mummers have, for more than a hundred years, been a deeply embedded part of Philadelphia traditions, and, crucially, all of the dancers and musicians wore blackface makeup.

But amid the civil rights struggle, that part of the costume became the focus of vociferous protest and litigation, with the argument that such makeup demeaned and embarrassed the city’s African American community. Along the way, when I lived in Indonesia, I discovered the old historical Dutch tradition of Swart Piet, Black Pete, Santa Claus’ slave helper. Swart Piet came dressed in a Moorish style costume and, yes, with blackface makeup. While the American Mummers makeup reaches back to the days of minstrel shows in the early 19th century, the Dutch tradition is even older than that Philadelphia tradition.

Moreover, white American minstrel-style musicians in the 19th century also usually performed in blackface, something not particularly noteworthy to most observers at the time. This carried on into the 20th century as well, and popular singers such as Al Jolson, in making The Jazz Singer, the first feature film with a full soundtrack, also recorded his popular numbers in blackface.

More problematically, this blackface tradition has carried on into more recent times, at least among some people. By then there clearly were conscious racial undercurrents. Three years ago, incumbent Virginia Governor Ralph Northam, a Democrat, found himself in a political firestorm when old university yearbook photos emerged showing him apparently wearing blackface, to the consternation of the African American community (among others) who had supported him in his election.

As CNN reported it at the time, “Democratic Virginia Gov Ralph Northam confirmed Friday he was in a racist yearbook photo showing one person dressed in blackface and another in the KKK’s signature white hood and robes, and apologised for ‘the decision I made to appear as I did in this photo and for the hurt that decision caused then and now’.” Somewhere along the way he tried to explain it as an attempt to show up at a student party dressed as Michael Jackson, as if that would make it all better.

Now as far as Prof Sheng’s circumstances have gone, he almost certainly was not trying to make a provocative racial statement about fake blackness. Nevertheless, it seems astonishing for someone teaching on a contemporary American university campus such as Michigan to have been blithely unaware of the complex currents and debates about identity.

At a minimum, Sheng should have thought to offer his students a contextualising introduction to what he was about to show them, why Olivier’s portrayal was both an extraordinary dramatic achievement and a product of its time, and why the question of authenticity in depicting someone of a different race has become an increasingly fraught question in contemporary culture. Or, perhaps, he should have simply picked a different version of Othello to show. Yes, hindsight offers 20/20 vision.

For the university administration, meanwhile, their alacrity in “solving” the controversy by blaming the professor and removing him from his class demonstrated failure in addressing questions of academic freedom, free speech and appropriate speech by university instructors. These three clearly run through this controversy.

Finally, of course, the students who felt offended chose almost immediately to protest against the class and insist on that chimera of a university as a “safe space”, rather than engage vigorously with their instructor about why he chose such a cinematic work. And, then perhaps, they might also have chosen to ask the obvious question of how Othello should be portrayed in an opera cast if the role is sung by a white singer — or can it only be sung by a black man?

Now, how about this as a reverse twist. When I was doing research on the history of the Johannesburg Civic Theatre back in the early 1960s, South Africa had its own brush with a strange incident of racial coding in a public performance. The then newly commissioned Civic Theatre was putting on a spectacular production of the Broadway work, Show Boat. Given that show’s subtext of racial prejudice and “passing”, from today’s perspective it seems to have been a most unusual choice for a South African theatre in the middle of the apartheid era.

To sing the role of Joe and his showstopper of a number, Ole Man River, the theatre had contracted Inia Te Wiata, a New Zealand opera singer, then living and working in London, to come to Johannesburg. But Wiata was a Maori, and, as a result, he would have been classified as coloured in the South Africa of the time. However, if so, he would not have been allowed on the same stage with the rest of the — white — cast. (Incidentally, the show featured two choruses, one black, one white in keeping with the story, but the stage was constructed so that the producers could argue that the two racial groups were never on stage together simultaneously, thus avoiding a political firestorm)

Some legerdemain with the South African government then ensued and Wiata was suddenly reclassified as a white person — because of a Scandinavian ancestor. Fortunately, Wiata didn’t need black makeup to deliver a mesmerising performance.

This question of racial typing on stage has become an important issue as Broadway slowly reopens as readers are reading this article. Returning to here and now, as The New York Times reported on 24 October, Hamilton has restaged What’d I Miss?, the second act opener that introduces Thomas Jefferson, so that the dancer playing Sally Hemings, the enslaved woman who bore him multiple children, can pointedly turn her back on him.

“In The Lion King, a pair of longstanding references to the shamanic Rafiki as a monkey — taxonomically correct, since the character is a mandrill — have been excised because of potential racial overtones, given that the role is played by a black woman.

“The Book of Mormon, a musical comedy from the creators of South Park that gleefully teeters between outrageous and offensive, has gone even further. The show, about two wide-eyed white missionaries trying to save souls in a Ugandan village contending with Aids and a warlord, faced calls from black members of its own cast to take a fresh look, and wound up making a series of alterations that elevate the main black female character and clarify the satire.

“Broadway is back. But as shows resume performance after the long pandemic shutdown, some of the biggest plays and musicals are making script and staging changes to reflect concerns that intensified after last year’s huge wave of protests against racism and police misconduct.

“‘We’re in a new world’, said Arbender J. Robinson, who was among the actors who expressed their concerns in a letter to the Mormon creative team. ‘We have a responsibility to make sure we understand what we’re doing, and how it can be perceived.’

“Although classic shows are often updated to reflect shifting attitudes toward race and gender when they are brought back to the stage as revivals, what is happening today is different: an assortment of hit shows reconsidering their content midrun. They are responding to pressure from artists emboldened by last year’s protests, as well as a heated social media culture in which any form of criticism can easily be amplified, while taking advantage of an unexpected window of time in which rewriting was possible, and re-rehearsing was necessary, because of the lengthy Broadway shutdown.”

With such questions swirling around, and with a parallel, growing debate among composers and critics about the putatively toxic orientalist exoticism of classics like Madame Butterfly and Turandot, among others, it seems a shame Bright Sheng did not at first grasp how black racial stereotyping might have instigated an explosive moment for his class of neophyte opera composers while they watched a masterful production of Othello. DM

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

Olivier was very clearly basing his portrayal of Othello on characteristic traits of recently arrived immigrants from the Caribbean. It was technically very impressive, but distractingly so, to the extent that I didn’t feel engaged at all.