OP-ED: POLICY AND LEADERSHIP

Morocco’s Essaouira: The tolerant city where things have always been done differently

Even as the great schism between the Muslim and Jewish religions deepened, Essaouira became the only Muslim city with a majority Jewish population, totalling 16,000. Jews were given the protection of the King’s personal seal.

The opening scene of Orson Welles’ acclaimed 1952 production of Shakespeare’s Othello pans the length of the Skala de la Ville, the 16th-century sea ramparts running along the Atlantic facing cliffs of the Moroccan city of Essaouira.

Today, as 70 years ago, the harbour is packed with blue boats, the tourists side-stepping piles of drying nets, the confusion of swooping gulls and coveting cats, and the open trays of skate, prawns and sardines destined for the seafood restaurants inside the city’s walls. The alleyways of the Medina exude a surprising calm despite the usual Moroccan scents of sandal- and lemon-woods, leather and spices, and the clash of colour of its clothes, carpets and ceramics.

The bastion’s walkways were used by Welles in a production which, despite the disappearance of several Desdemonas and at least one Iago along with early financial difficulties, earned the American actor-director a Palme d’Or.

Locals were recruited as extras, the Jewish town tailors making suits of armour from sardine cans. One of these stand-ins was a young schoolboy, André Azoulay, later to become counsellor to the King of Morocco.

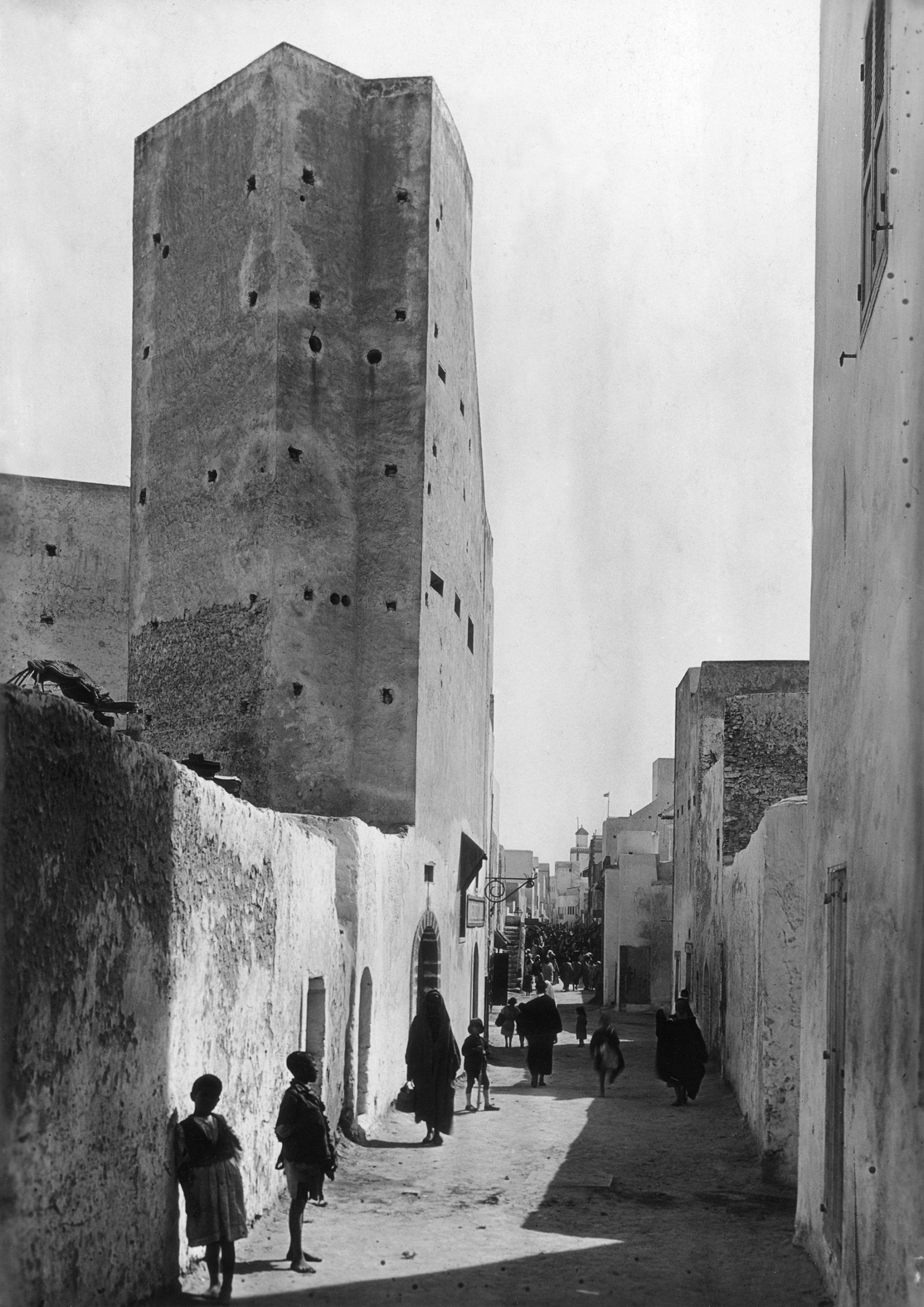

circa 1910: A street in the Mellah, or Jewish quarter of Mogador (Essaouira) in Morocco. (Photo: Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

Just as Welles was able to turn around his great production, Azoulay, too, has stood at the helm of a turnaround in the fortunes of Essaouira. As sub-Saharan Africa struggles to find a formula to better access investment from 88% of the global economy which lies outside the sub-continent, it might do well to look at what has been achieved in the ancient and modern versions of this Atlantic city.

During the 19th century, Sultan Mohammed Ben Abdallah, Mohammed III, took the fortress city — partly built by the Portuguese 200 years before — and turned it into an early version of a Special Economic Zone. By implementing a zero per cent tax — business or personal — he drew in skills and the finance to turn Essaouira (then known as Mogador) into a hub of trade between Europe and Africa.

A French engineer, Théodore Cornut, was among those tasked to build the fortress and city along modern lines, the city being renamed from the original Mogador to “Es-Saouira”, or “the beautifully designed”.

Essaouira is a place where things have been done differently. Even as the great schism between the Muslim and Jewish religions deepened, Essaouira became the only Muslim city with a majority Jewish population, totalling 16,000. Jews who took up the offer were given the protection of the King’s personal seal.

Essaouira became a place where Muslims and Jews lived side by side with 37 synagogues in the Medina intermingled among its mosques. It became a thriving global centre of trade with 27 foreign embassies from as far afield as Brazil located there.

Trade thrived with volumes about double those of Rabat, the port servicing West Africa and the Sahel and, inland, the city of Marrakesh 200km away. A centre of diplomatic activity, banking links with Europe made doing business easy. Known as Timbuktu’s port, Essaouira linked the Sahelian hinterland with Europe.

circa 1910: A street in the Mellah, or Jewish quarter of Mogador (Essaouira) in Morocco. (Photo: Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

Then the politics changed, and so did the city’s fortunes. Following Morocco’s alliance with Algeria against France, coupled with wars with Arab states, Essaouira was bombarded and occupied by the French in August 1844. France maintained an administrative and military presence from that time. From 1912 to 1956, it was part of the French protectorate of Morocco.

The founding of Israel coupled with Moroccan independence and wars with Arab states led to most Sephardic Jews leaving the kingdom. Today Morocco has 2,500 Jewish inhabitants.

By the 1950s the city had become run-down.

In 1991, the since-deceased King Hassan II of Morocco rekindled the old relationship between Jews and Muslims, when Andre Azoulay became the 11th Moroccan Jewish Counsellor to a Moroccan king. Azoulay set about restoring Essaouira’s ancient Medina, and the city’s history of religious tolerance and economic innovation.

Its battlements, walls and city gates have been recognised by Unesco as, “an exceptional example of a late-18th-century fortified town, built according to the principles of contemporary European military architecture in a North African context” and declared a World Heritage Site. Azoulay has been nicknamed locally as the “man who speaks to stones” for his efforts to rebuild the old city.

Bayt Dakira, a Jewish heritage house, was built at Azoulay’s instigation to honour the historical role of Jews in Morocco — the only museum of this kind in the Muslim world.

It’s a rich history. Inside the heritage house, with its reconstructed synagogue, are portraits of the life of a dynamic community including the likes of Victor Elmaleh, who emigrated from Morocco, and started his business in the United States by importing dates from, and tyres to, Morocco. Later he became, in the 1950s, the importer of Volkswagens, before turning to real estate. The Moroccan-Israeli actress Ronit Elkabetz; the first Jewish person elected in UK history, the famous UK Secretary of State for War, and Transport Minister, Leslie (later Baron) Hore-Belisha; Rabbi David Pinto; the Israeli politician Jacques Amir; and the counsellor Azoulay are among the city’s notables.

The painstaking restoration has lured tourists, nearly one million of whom visited pre-Covid. But this, too, has not happened by chance. They are drawn by a carefully thought-out plan putting culture at the centre of Essaouira’s offer.

Essaouira has also been recognised as a centre of innovation. Azoulay told a French Chamber of Commerce event of “the double rendezvous that history can give to Essaouira with, on the one hand, the radical change that it will experience the economic, industrial and commercial landscape for the post-Covid days and, on the other hand, the accentuated focus of tomorrow’s investors in the direction of clean industries, bioproducts and the optimisation of various sectors of renewable energy”.

Among Essaouira’s economic advantages are its fisheries and its unique Argan trees, which produce oil and cosmetics. At the Beni Antar Cooperative outside Essaouira, 200 women are employed extracting the seed from the Argan nut. The industry survived the Covid-19 lockdowns by allowing women to crack the nuts at home.

Morocco produces 100,000 litres of Argan oil annually with Israel and Korea among its largest customers in a $2-billion annual market.

And it has become a trend-setter for innovation and the arts. During the 1960s, as the city struggled to rebuild its identity, it went through a hippie phase, playing host to Frank Zappa and Jimi Hendrix, among others, the latter supposedly writing “Castles in the Sand” about Essaouira.

Then, in 1996, the city held its first Gnaoua World Music Festival. Organisers were taken by surprise when tens of thousands of music lovers showed up, draining the city’s supply of bread and milk. Numbers would grow to 600,000 before a new plan was adopted to split into more, smaller festivals.

These days Essaouira is host to 11 annual music festivals a year including ones that celebrate chamber music and opera, jazz, trance and, for the younger set, techno.

The revival of Essaouira and Morocco’s economic resurgences are evidence of how, then as now, policy and leadership matter. It has taken three decades of concerted effort to embed Essaouira’s new economic narrative and for Azoulay to state: “it is known as a happy city, a place which shows we are all humanity finding a way to live together without frontiers, without barriers. There are not many places where Judaism and Islam are in such proximity and intimacy.”

A bas-relief of Orson Welles in a small square near the Medina remembers the actor-director who once strode Essaouira’s walls in his search for a different perspective. As Azoulay reminds us, “we are not spectators in someone else’s play. We have to change things ourselves, with leadership, but from the bottom up.” DM

Greg Mills and Ray Hartley were in Morocco with the Brenthurst Foundation.

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

Comments - Please login in order to comment.