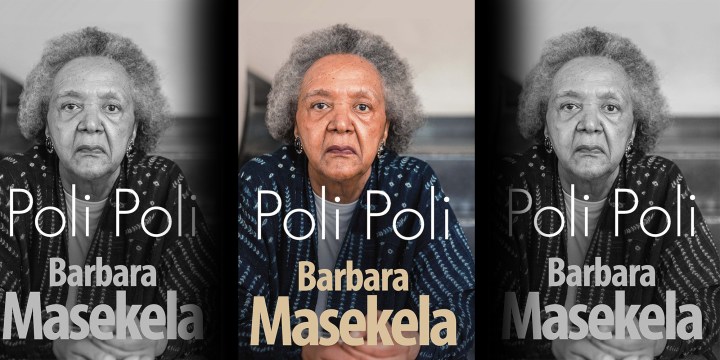

BOOK EXTRACT

Poli Poli: The rise of rebellion and the transition from fighting talk and peaceful resistance into armed struggle

In ‘Poli Poli’, Barbara Masekela powerfully conveys the realities of life under apartheid KwaGuqa in the 1940s, Alexandra township in the 50s, and one of the oldest girls-only schools in KwaZulu-Natal, Inanda Seminary. The memoir follows her grandmother, a beer brewer and seller who lived through the immediate aftermath of the South African War; her professional parents’ hard work and determination at a time when the state worked to shut doors for black people and their efforts to secure opportunities and safety for their children; and her going into exile to Ghana in 1963. ‘Poli Poli’ is published by Jonathan Ball.

Apartheid was showing its teeth. Forced removals, prison gangs working on white farms and in public spaces, especially in the small rural towns, slavery on the potato farms, pass raids, banishments and namings trailed all over the land. But the voices of resistance, hoarse from screaming out the injustices, were also rising. And as we listened we heard of boycotts and the defiance campaigns in the unlikeliest of places.

Then the people answered with the Freedom Charter. The deafening clamour for “freedom in our time” was in a moment eclipsed by the Treason Trial. It was my first year at Inanda when 156 leaders of the ANC and their allies were charged with treason. It was as though the guardians of the people had suddenly been taken away from them. We lived in a country where executions, especially of black convicted criminals, were a common feature. The sudden and stealthy nature of the arrests, which were effected so that they were simultaneous nationwide and carried out at the crack of dawn, was eerie. It was a sinister occurrence, a naked show of the power of the security forces over those who dared to challenge the state. This national swoop hit close to home. Among the arrested were Chief Albert Luthuli and MB Yengwa, the husband of Edith Sibisi, our most senior African teacher at Inanda. It had a huge psychological impact on the girls at school and became the moment when many of us began to consider our future role in the unfolding political sphere.

Fighting talk and peaceful resistance merged into armed struggle, giving birth to Umkhonto weSizwe and other armed resistance groupings as the only alternative to the ever-burgeoning repression. Nelson Mandela, in a dramatic and unexpected move, subsequently left the country secretly to train as a guerrilla and to seek assistance from independent Africa. There was a swell of pride when he returned to the country and lived underground — and, for a while, eluded capture. He was dubbed the Black Pimpernel; the word “terrorist” became commonplace as pamphlet bombs detonated in city centres, scattering leaflets calling for resistance against the apartheid regime. The presence of what were called “subversive elements” in the face of heightened repression deepened the hope for change. No amount of mass arrests, detention or torture seemed to deter the spread of rebellion in the heart of the urban and rural areas. Change would be delayed, but it was inevitable, and it was beginning to make itself evident in the most unexpected quarters.

A few years later, Manto Mali (Manto Tshabalala), my erstwhile prefect at Inanda, was in one of the first groups to leave the country to join the liberation movement in Tanzania. Later on, another Inanda girl, Joyce Sikhakhane, also made her mark in the Struggle. But they are only a few of the many Inanda girls who made a lasting contribution to the cause of freedom in South Africa.

Our generation had been raised to step in whenever the breach of any convention became a threat to human dignity. So as I scrubbed, polished, baked and cooked, sometimes with Sybil on my back, I took on my mother’s burdens. I did not relish the work — at times, I even resented it — but it always won me a special place in the hallowed universe of my mother. There were many whispers, many people disappearing to join the struggle in exile. Among them was Alfred Nzo, who had worked with my father at the Alexandra Health Committee. Another outstanding leader from Alexandra was the unforgettable Thomas Titus Nkobi, outspoken and unpretentious, without fear or bias, who became the longest-serving treasurer general of the ANC and a legend for the honest manner in which he shepherded the finances that kept the organisation afloat during the most difficult time of repression for decades in exile and at home. I was to meet many of them in Lusaka when I went to study at the University of Zambia. Their warmth and kindness towards me in exile was a validation of my parents’ devotion to the service of the people of South Africa. In a world where people from different parts of the country were meeting for the first time away from home, it was heartwarming to meet men and women who knew my parents and appreciated their work.

When my sister Elaine was about eight she spoke Xitsonga, which she was learning from MaMatsheka, who had come from a Tsonga village to live with her husband, a clerk at the Alexandra Health Committee. In the townships, Tsongas were called Shangaans, and often ridiculed for their language and their rustic dress style. In particular, their love for bright primary colours was mocked and earned the scorn of township fashion icons who favoured the American sporty style or the straight British tweed. At school there was general teasing of all ethnic groups, especially those who came from the furthest parts of the old Transvaal. In the urban bustle of making a living, the narrow differences between customary origins were muting into a shared clamour for change, and the stereotyping based on tribal background was retained in the undertones of tired jokes in closed groups of intimate homeboys and homegirls who dared not to speak their bias publicly.

My mother spoke almost all the African languages, which enhanced her community work and endeared her to all. Very few called her a coloured to her face because, like many others, she had been raised to speak isiNdebele fluently. With her aptitude for languages, she also spoke isiXhosa and Sepedi without an accent. This was not a remarkable skill because she had been raised in an African environment, as had many of her background, born before apartheid. But in an increasingly racially defined society it would become the norm that people of her background would eschew any commonality with Africans, choosing Afrikaans and English as their only languages. My mother blended easily into all the communities she lived in, although there were rare occasions when there were murmurs about her background and racial epithets were deliberately expressed loudly enough to be heard. ML/DM

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

“Pamphlet bombs” were not the only kind of bombs being detonated during this time. Funny how certain little inconvenient details always seem to be left out…

These ‘struggle icons’ owe it to the future generations to be honest about their actions during this time. Yes, the situation was bad, but if you are going to paint a picture, at least paint a full picture.