OUR BURNING PLANET

Toxins, dioxins and potential risks to grandchildren from the UPL chemical inferno

With the barest trickle of information seeping beneath the closed-door investigation into the UPL chemical disaster in Durban, the public is still in the dark about health impacts and exposure levels from airborne toxic chemical exposure. But studies on people and animals exposed to several of these chemicals point to significant health problems that could potentially extend several generations into the future.

Viktor Yushchenko was on the point of gaining power as president of Ukraine in 2004 when he became seriously ill and was flown to Austria for specialist treatment. He was poisoned deliberately, possibly by Russian agents.

Medical experts later determined that the poison was a highly toxic chemical known as 2,3,7,8-Tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin (TCDD).

TCDD is a colourless, odourless but highly toxic dioxin, one of several by-products of a wide range of manufacturing and heating processes including smelting, chlorine bleaching of paper pulp and the manufacturing of some herbicides and pesticides.

Yuschenko survived, but was left with a severely disfigured face, with his skin bloated and pockmarked by chloracne (a severe form of acne linked to exposures to dioxins).

Belarusian politician Viktor Yushchenko before and after poisoning. (Image: AP)

TCDD was also a component of the infamous Agent Orange herbicide cocktail that the US military sprayed over large parts of Vietnam. It was later linked to an abnormally high incidence of human miscarriages, skin diseases, cancers, birth defects and congenital malformations.

The names “TCDD” and “dioxins” also cropped up when a chemical plant exploded near the Italian town of Seveso in 1976, leading to the subsequent evacuation of more than 700 residents.

Researchers estimated that less than 30kg of TCDD was released into the air, water and soil around Seveso, with residents in the path of the aerosol cloud developing nausea, headaches, eye irritation and skin lesions.

In the ensuing weeks, there were several cases of animal and plant deaths and nearly 200 cases of chloracne were reported some months later, mostly in children.

More significantly, however, medical researchers are still recording significant health impacts among the children and grandchildren of Seveso residents more than 40 years later.

These include a significant increase in cancer cases among women, decreased male and female fertility and increased risk of infertility in women (as well as their daughters who were exposed to TCDD in the womb) and a skewed sex ratio (more female children).

Reflecting on the lessons learnt from the Seveso chemical explosion decades later, University of California public health researcher Prof Brenda Eskenazi and colleagues noted that there had since been a series of similar natural and human-made environmental disasters.

“The accident in Seveso provides an important example of the steps epidemiologists and related health professionals can take in the aftermath of a disaster to document its health effects. Epidemiologic research only became possible in Seveso because of the rapid establishment of a long-term health surveillance program of the population, which included — critically — collection and storage of biosamples from a large number of affected individuals, despite the fact that methods to analyse exposure in those samples had not yet been developed.

“The great degree to which our understanding of the human health effects of dioxin exposure has evolved since 1976 is directly attributable to the foresight of the health professionals who took these critical first steps in Seveso, and to the dedicated participation of families in research studies over the last four decades.”

Back in Durban, however, it remains unclear whether any samples of dioxins and furans (or blood and tissue samples) have been collected — nearly 12 weeks after the 12 July arson attack on the Cornubia toxic chemicals warehouse.

If any dioxin samples have been collected, UPL is not saying — nor is it revealing the test results to the public (see UPL’s full responses further below).

According to the World Health Organization, the analysis costs for dioxins are very high, and vary according to the type of sample, but range from over $1,000 for the analysis of a single biological sample to several thousand dollars for the comprehensive assessment of release from a waste incinerator.

Nor is it clear whether a systematic medical surveillance project will be mounted to record short and long-term health impacts among Durban communities exposed to nearly 12 days of airborne clouds of burnt chemical residues from the Cornubia warehouse, or subsequent exposure through water, soil or residual chemical dust deposits.

UPL South Africa commercial director Jan Botha issued a media statement on 23 September stating that his company had appointed a specialist company to conduct a human health impact (risk) assessment. He was also “pleased that no fatalities or hospitalisations as a result of the chemical spillage have been reported to date”.

So, everything’s hunky-dory?

Botha’s comments have raised the ire of several civil society health watchdogs, including groundWork environmental health campaigner Rico Euripidou, who remains deeply concerned about the poor public health response by both government and UPL, and the failure to rapidly put a comprehensive health surveillance system into place.

He suggests that without a systematic monitoring programme, any unexpected or unusual health events, such as an increase in heart attacks among the elderly or miscarriages in pregnant women, would go largely undetected.

Euripidou, an environmental epidemiologist who trained at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, has also stressed the need to collect samples of dioxins and furans given that the gutted UPL warehouse — located close to several densely populated suburbs north of Durban — was the repository of vast quantities of pesticides, herbicides, insecticides, fungicides, rodenticides, surfactants and fumigants.

Some of the chemicals included 2,4-D, glyphosate, mancozeb and chlorpyrifos — the very same chemicals linked to the discovery of irreversible facial and other deformities in chimpanzees in Uganda’s Kibale National Park due to pesticide spraying of adjoining tea plantations.

The primate and chemical research team found a variety of deformities that included smaller nostrils, cleft lip, limb deformities, reproductive problems and hypopigmentation in chimpanzees. They remarked that due to the genetic similarity to humans, wild primates could act as sentinels for altered embryonic development in humans exposed to similar pesticides.

But there are some far more disturbing dimensions that underline the need for more intensive surveillance in Durban.

These include the potential for chemicals to induce transgenerational epigenetic health impacts, a relatively new field of research pioneered by Washington State University biology professor, Dr Michael Skinner.

Dr Michael Skinner. (Photo: Washington State University)

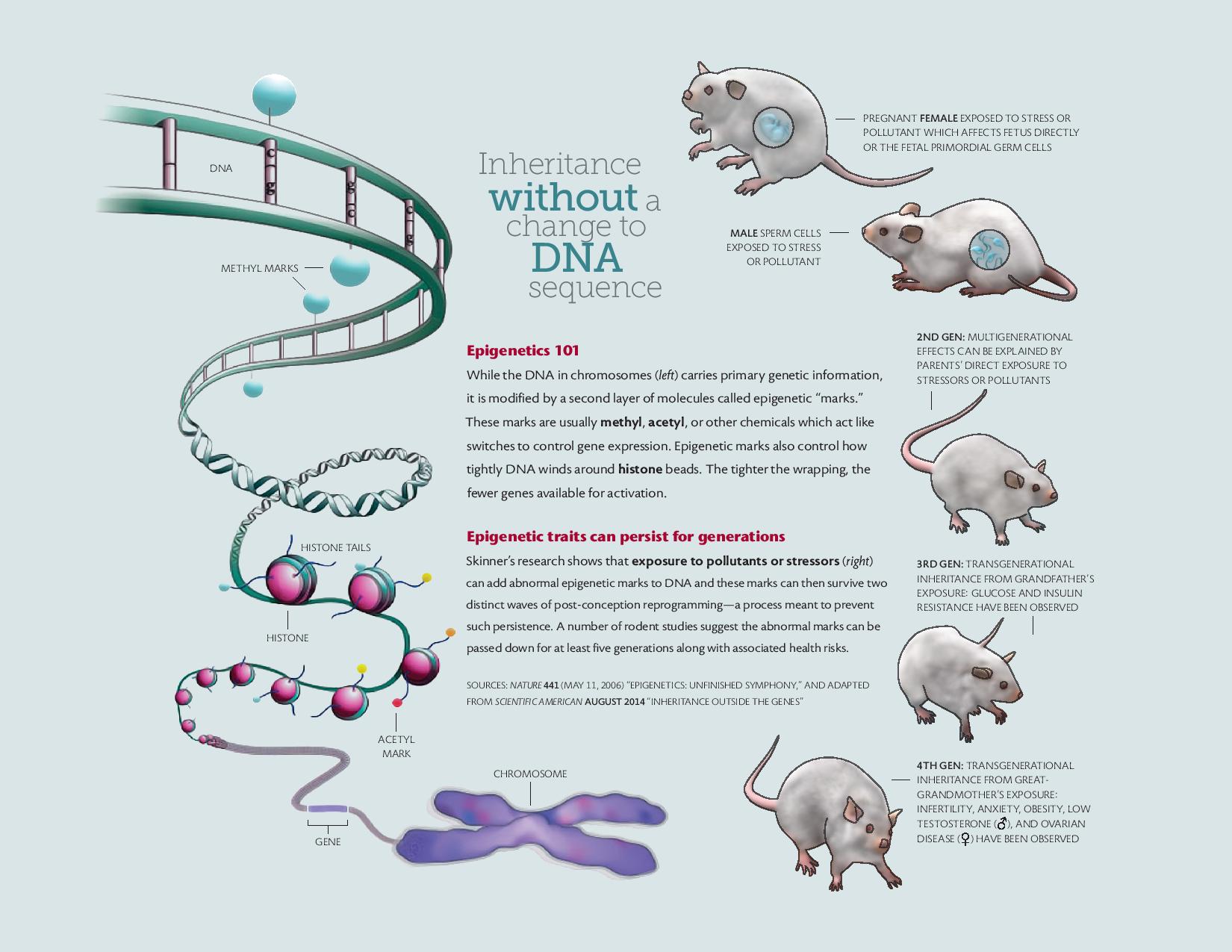

In simple terms, Skinner’s research group has sought to demonstrate that certain chemicals that your great-grandmother was exposed to could cause disease in you and your grandchildren.

A fuller explanation of his research work can be viewed in this 20-minute TEDx talk.

“We have tested around 20 different environmental toxicants — everything from glyphosate to dioxins, those types of things — and basically all of them will promote a transgenerational epigenetic disease state,” he told Canadian Broadcasting Corporation science journalist Bob McDonald in a podcast on 18 June.

Skinner suggests that while these toxins do not cause mutations of the DNA, they can permanently “reprogramme” the sperm and eggs of exposed people and animals so that their offspring become more susceptible to a variety of impacts (ranging from marrow degeneration, behaviour and anxiety effects, obesity and diseases of the prostate gland, ovaries or kidneys)

Source: Washington State University

Skinner told Our Burning Planet that he was not aware of the full details of the recent Cornubia chemical disaster, but suggested there could be similarities to dioxin exposures seen in previous industry accidents. He also hoped that local scientists would be engaged to set up long-term studies to monitor the short-term and long-term generational impacts.

“The immediate health impacts are always the focus, but the long-term and generational impacts may be far more dramatic… Offspring and grand offspring can be monitored over time if the clinical cohorts are established now.

“This was done in Seveso and demonstrated various pathologies (diseases or injuries) in later generations that were more dramatic the closer they lived to the site.”

However, this would require considerable financial support, either from the industry or government.

What do the national and provincial health departments have to say on these issues?

Both departments were asked on 28 September to confirm whether any air, water and soil samples had been collected for dioxin analysis. They were also asked whether any blood or tissue samples had been collected from people in exposed communities and to provide full details of short and long-term health surveillance measures. Neither department responded.

What about the Joint Operations Committee (JOC) — the interdepartmental committee of national and provincial departments that is investigating the disaster?

Similar questions were sent to the JOC, but no response was received.

What does UPL have to say on these issues?

“UPL has spared no expense or expertise in addressing the consequences of the arson attack on its facility on 12 July, even though the event was entirely beyond its control, and the consequential damage was a result of an unprecedented break down in the rule of law.

“Significant resources, R177 million to date, have been directed to appointing an experienced, expert team to oversee the clean-up and remediation efforts — as well as any health impacts for the surrounding communities. UPL is committed to working constructively with all relevant parties to mitigate the impact of the fallout from the violent attack on our warehouse facility.”

Please elaborate on the investigation methods used by UPL and its consultants to ascertain that there were no hospitalisations or fatalities associated with the UPL chemical disaster.

“Apex Environmental has been appointed to conduct a human health impact risk assessment. The study plan was the subject of detailed scrutiny at a recent meeting of the relevant authorities and is being revised and finalised. It must be stressed however that while it includes an assessment of actual human health impacts, the principal aim is to determine an appropriate sample and the range of appropriate tests, so that the likely human health impacts — acute, medium and long-term — can be determined.

“Whether, and to what extent there should be additional or further interventions including long-term surveillance/monitoring will flow from the results.”

Does UPL accept that the release of large volumes of toxic chemical compounds in the aftermath of the arson attack at its warehouse has the potential to result in significant health impacts, including long-term impacts, for communities exposed via air, water or soil? If so, what is the range of potential health impacts that may be expected in exposed communities? If UPL does not accept this possibility, on what basis has it reached such a conclusion?

“The human health impact risk assessment will ascertain precisely what human health impacts were experienced, and what might in the future be expected. Preliminary indications are that there were a relatively limited number of acute human health impacts, but at this stage UPL cautions against speculation until the studies have been completed.”

Has UPL SA engaged with its parent company in Mumbai to timeously initiate and to fund a comprehensive and long-term health monitoring surveillance project for exposed communities? If so, what are the relevant details? If not, why not?

“This has already been dealt with. The human health impact risk assessment is underway and will inform the way forward regarding ongoing monitoring.”

Can UPL confirm whether the consultants it has appointed to investigate the incident have taken samples of any dioxins, furans and dioxin-like compounds in the air, water, soil or other media? If so, how many samples were collected for these compounds and what are the measurement results reported so far? If no samples of dioxins and furans have been taken, why not?

“Continuous air monitoring, soil and water sampling has been taking place, and is ongoing. The test results form part of the weekly and monthly reports to the authorities.”

Have UPL consultants collected any blood samples, tissue samples or any other biological samples from people in exposed communities? If so, how many blood/biosamples were collected; when were they taken and what were the results? If no biosamples were taken, why not?

“Comprehensive blood and other tests will be conducted as part of the human health impact risk assessment.”

Has UPL sought the advice/assistance of any medical surveillance experts who have been involved in monitoring human health impacts following chemical accidents such as Seveso (1976) or similar incidents? If so, what are the relevant details?

“The human health impact risk assessment is following best international practice, in a process going through detailed pre-scrutiny by the health authorities. It is being guided by them.” DM/OBP

[hearken id=”daily-maverick/8738″]

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

Now we are delving deeper with international comparisons. This is a major international incident which will be in the environmental text books in the future. An UPL cover up in a corrupt African country does not make good international reading for them and for us even worse with ongoing health defects.