MAVERICK CITIZEN BOOK REVIEW

The Poisoners: an unfinished history of poisoning and ultimately a political story to be continued

Imraan Coovadia insists that the veil around the poisoner, one of secrecy, mistrust and collusion, is also a veil around history itself. The horrors of the past – in Rhodesia, in apartheid South Africa and also in the ANC – seem to have been quickly forgotten or swept under the rug, with the poisoners were quickly rehabilitated or forgotten.

Rebecca Davis’s review of Imraan Coovadia’s The Poisoners is a superb beginning to a conversation on the veiled role of poisons in southern African politics that cuts to the bone of southern African white supremacy along with the factionalised ANC, in particular its Zuma/Magashule/Mabusa wing.

She brings out the derring-do astonishment of this book – a book which Coovadia, a fine author of fiction and non-fiction, chose to write very close to the facts with little authorial presence except to bring home the moral of the story after it has been amply demonstrated by those facts.

The story broadcasts itself in the manner of a non-fiction novel, with characters jumping off the page in that larger-than-life way that one thinks of as characteristic of great literature – Joseph Conrad, VS Naipaul or even Thomas Pynchon. These characters include Alan Brice, recruited to kill Robert Mugabe; Robert Symington, co-orchestrator of the Rhodesian poisoning programme with Rhodesian Minister of Defense PK van der Bly, who (and here Rebecca Davis quotes Coovadia) “wanted to be a film star and play Tarzan” but ended up playing a game of see Jane, kill Jane; Wouter Basson, “Dr Death” of the apartheid state, now happily practising medicine in the Western Cape; not to mention a cast of American weirdos, Scottish adventurer/reprobates, and ANC Struggelati, vying among themselves for the upper hand in a context of paranoia about who among them had been turned by the apartheid state.

Behind the veil is Russia, master-nation of poisoners where perhaps the ANC learnt the fine art of it, and the US/CIA with its secretive chemical weapons programmes launched during the Korean War of the 1950s.

Poison is cure: the cure for threats, perceived or real, that challenge a state (or family, in the case of Zuma and his wives) that is itself veiled from the public eye, a state of authoritarian non-transparency with a closed cabal of ministers and/or chiefs whose internecine struggles for dominance and supremacy over competitors within or revolutionaries outside are largely shielded from the citizenry.

Prompted by the paranoia of politics filled with spies, pretenders and wannabes, poisoning is born of the politics of non-transparency and secrecy. Its goal is simultaneously to kill and erase all traces of the killing, as if it never took place.

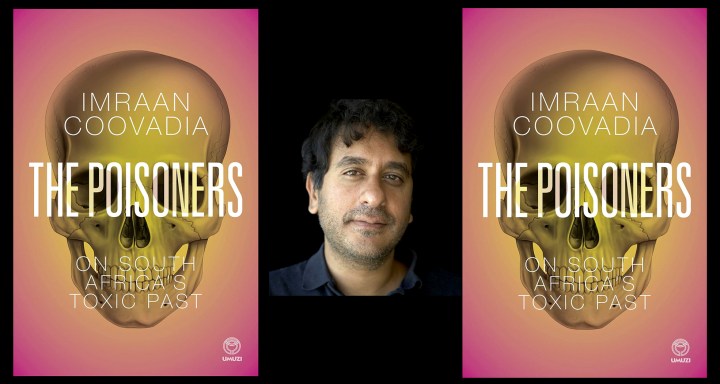

The story broadcasts itself in the manner of a non-fiction novel. Wouter Basson, ‘Dr Death’ of the apartheid state, is now happily practising medicine in the Western Cape. (Photo by Gallo Images / Foto24 / Lisa Hnatowicz)

Unlike rushing up to a person and shooting them in the head, poisons remove the poisoner from the scene of the crime, which is why the Nazi death camps were located outside of Germany in Poland (the “East”) and all records of the killings were themselves veiled in euphemism. And why Siberia – clearly off the beaten path – became the rest stop for dissidents the state wished to remove from public life.

Poisons are so central to the realpolitik of the 20th century that its history reads like a parade of technological witchcraft. From the gassings of World War 1 to the CIA’s investment in chemical weapons, to Iran, Iraq, China, North Korea and, of course, Soviet Russia, where poisoning had long played a role in the politics of Czar-ship, a role expanded to suit state control over individuals considered unruly by the KGB.

The amount of top research that has gone into the creation and deployment of poisons in Russia, the US and also Rhodesia and apartheid South Africa, demonstrates that poisoning is as much a part of the history of medicine as nuclear armament is part of the history of physics.

Science is never free of politics. Even if its truth claims depend on sufficient autonomy from ideology to be justified by experiment, theory and the ongoing development of scientific knowledge. A point poisoned by Thabo Mbeki when he insisted that the autonomy of medical consensus around the cause of AIDS (the HIV virus) was a mere smoke for neocolonial supremacy over the black man’s sexual identity, disempowering Africa from its capacity to solve its own problems in its own way, a capacity he wished to see emerge (or re-emerge) in an African Renaissance.

The result: 320,000 preventable deaths in South Africa between 2000 and 2005.

Coovadia insists that the veil around the poisoner, one of secrecy, mistrust and collusion, is also a veil around history itself. The horrors of the past – in Rhodesia, in apartheid South Africa and also in the ANC – seem to have been quickly forgotten or swept under the rug, with the poisoners quickly rehabilitated or forgotten.

Whether this also pertains to South Africa’s memory of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission is another matter. The point is that in spite of its bold and essential need to revisit the poisons of the past, the TRC never dredged up the story of the poisoner except when it was linked to individual human rights violations. No systemic story of poisoning emerged, nor was it expected to emerge.

Why is this a loss?

Coovadia makes a rare and rewarding narrator’s appearance at the end of the book to address this question:

“For almost half a century, from 1973-2020, political poisoning, and the stories South Africans imagined and circulated about being poisoned, were ways in which the hostility and distrust embedded in our society and its neighbours was expressed. By the standards of modern war the casualty figures of killing by poison in southern Africa were moderate, but the paranoia sown in the targets of Symington and Basson is imprinted in the conspiratorial culture of the party organisations which came to rule in South Africa and Zimbabwe. That may be the greatest cost… [the] unbounded damage human beings do to each other and to themselves when they array themselves into inimical groups, in the process losing hold of the understanding, given to each of us by nature, of elemental good and evil.” (pp. 236-237)

South Africa has fallen into a state of near total mistrust. The factions of the ANC do not trust each other. Citizens do not trust the government. Citizens do not trust one another in adequate measure for a sustainable democracy. In this condition of poisoned democracy the story of poisoning is central, an icon of human failure.

The story broadcasts itself in the manner of a non-fiction novel. These characters include Alan Brice, recruited to kill Robert Mugabe. (Photo: Pascal Le Segretain/Getty Images)

The book begins with Jacob Zuma and ends with Jacob Zuma, Ace Magashule and David Mabuza – recently returned from Russia where he claims to have been cured from poisoning, even if one wonders whether Mabuza really went to Russia to watch ballet.

It begins and ends in the present, as if instead of “The End” the book’s final line should have been “To Be Continued”. And by “To Be Continued” I mean both the future poisonings and claims of being poisoned that will undoubtedly follow, and the national conversation that needs to take place around mistrust, secrecy, internecine power grabs, and accountability, not to mention the narcissistic grandiosity of the person empowered to poison, the role of fantasy in politics, and the place of science, medicine and spirit cultures in, and their complex intersection with, Western medicine. Poisoning is necessary to that conversation and a good way into it, since the poisoner – real or imagined – remains central to South African politics.

This is a must-read book and a great-read book. I would be so delighted were Professor Coovadia to take tea with me to discuss it further. We could have sandwiches with dill and a dab of mustard… gas. DM/MC

The Poisoners, On South Africa’s Toxic Past 1973-2020 by Imraan Coovadia is published by Umuzi Press. Daniel Herwitz is the Frederick G. L. Huetwell Professor of Comparative Literature, Philosophy and History of Art at the University of Michigan.

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

Comments - Please login in order to comment.