ISS TODAY ANALYSIS

Rwanda’s foreign policy objectives appear focused on economic development rather than Africa policing

The country’s controversial deployments in the CAR and Mozambique should be seen as military diplomacy in support of economic ambitions.

First published by ISS Today.

Paul-Simon Handy, Senior Regional Adviser, ISS Addis Ababa and Dakar.

Rwanda’s recent military deployments in July in Mozambique and in November 2020 in the Central African Republic (CAR) have raised criticism. Rwanda is one of Africa’s biggest contributors to United Nations peace operations, but its latest deployments followed bilateral arrangements made despite multilateral interventions in Mozambique and the CAR. Some analysts have asked whether Rwanda is becoming a new policeman in Africa.

Beyond the controversy raised by these deployments, it’s important to assess what appears to be Rwanda’s comprehensive approach to diplomacy in Africa. At first glance, the interventions in the CAR and Mozambique are reminiscent of late Chadian president Idriss Déby Itno’s military support to neighbouring countries. But the pax tchadiana differs significantly from the emerging pax rwandana.

Kigali’s recent deployments seem to reflect a grand foreign policy strategy aimed at securing Rwanda’s interests in the long term while building strategic African partnerships to address the country’s structural challenges.

Rwanda is a small landlocked country with a high population density and few natural resources, unlike some of its neighbours. It has undergone a remarkable post-genocide development trajectory and is widely acclaimed for its economic growth, poverty reduction rates, public safety and security.

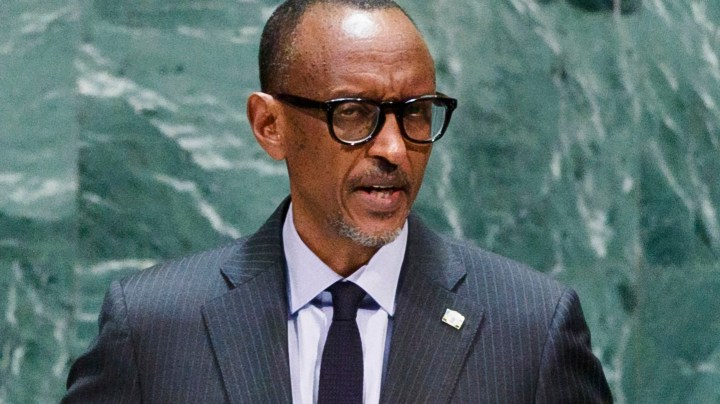

However, its development success in the past 25 years is due mostly to foreign aid. The fragility of this showed in 2012 when some donors suspended cooperation following accusations that Rwanda had supported the Democratic Republic of the Congo’s (DRC) rebel movement M23. To limit Rwanda’s dependency on foreign aid, President Paul Kagame established the Agaciro Development Fund, which aims to improve the country’s financial autonomy.

To diversify the economy and increase its self-sufficiency, Rwanda is mobilising its main assets — military professionalism, political stability, and ‘brand Rwanda’ — to benefit its foreign policy. Both the CAR and Mozambique deployments should be seen as military diplomacy supporting economic ambitions that nurture the country’s soft power.

The deployments indicate at least two things. First, Rwanda’s capacity to operate in countries with which it doesn’t share borders. Military support to Mozambique was a masterpiece in rapidity and efficacy. In the CAR, Rwanda’s campaign alongside Russian instructors and the CAR defence forces was bold and focused, with a limited timeframe.

Second, Kigali has the diplomatic ability to broker transactional deals with African countries. Rwanda’s bilateral deployment in the CAR resulted from a military cooperation agreement signed in 2019 between Kigali and Bangui. A series of economic partnership agreements complement this security cooperation.

In the same vein, DRC President Félix Tshisekedi and Kagame signed an agreement on the common exploitation of gold in June 2021. Pressured by traditional development partners, Rwanda opted to increase cooperation with fellow African states.

While Rwanda’s membership in the Economic Community of Central African States (Eccas) and in the Francophonie could justify its involvement in the CAR, the situation is different in Mozambique. Rwanda isn’t a member of the Southern African Development Community but shares a membership in the Commonwealth with Mozambique.

Mozambique does however border on Tanzania, and Rwanda gets many of its imports from the port of Dar es Salaam. A destabilisation of Tanzania could impact Rwanda’s economy. Regional and continental economic integration is a key tenet of Kigali’s foreign policy and one of the strategic options adopted to mitigate the country’s geographic disadvantages.

Kagame’s enthusiasm for free trade also aims to reduce the costs of transport and energy that hamper Rwanda’s economic development. However, this interest is not limitless, as shown by the frequent border closures with Uganda since 2019 due to long-standing tensions between the two countries. Rwanda’s obsession with perceived or real external security threats could pose a severe risk to the country’s foreign policy ambitions.

Unlike Chad, which also provided security services to boost its international image and protect itself from scrutiny, Rwanda’s military diplomacy is just one tool to project ‘brand Rwanda’ on the continent. And unlike many African states, the country’s brand is associated with effectiveness in security matters and the management of public affairs. Even if international perceptions of Rwanda are polarised, Kagame is regarded throughout Africa as a competent head of state.

This perception helped increase the number of positions Rwanda has filled in various international organisations. Former foreign minister Louise Mushikiwabo was elected secretary-general of the Francophonie. Former National Bank of Rwanda (BNR) deputy governor Monique Nsanzabaganwa was elected deputy chairperson of the African Union Commission, tasked with improving the implementation of the organisation’s reform.

Finally, former BNR governor François Kanimba was elected to the critical position of Eccas Commissioner for the Common Market, Economic, Monetary and Financial Affairs last year. And this was just after Rwanda returned to the organisation 20 years after withdrawing.

Rwanda is an interesting case study of African foreign policy. It combines hard (military) and soft (socio-economic performance and international perception) power to attain domestic and global goals despite its deep structural challenges.

Power in international affairs is traditionally analysed through the lens of material power — a composite of geographic size, population, military capabilities, natural resources and economic output. Rwanda’s foreign and security policy choices break new ground as the country’s diplomatic agility offers new perspectives. Its experience shows how small and medium-size countries could optimise their assets on the international stage and exert some degree of influence.

The Rwandan case also sheds light on African multilateralism, especially when powerhouse countries struggle with internal challenges or can’t lead on continental and regional issues due to a narrow vision of their interests. The emergence of smart powers like Rwanda may provide an alternative way to address pressing and long-term continental challenges. DM

Paul-Simon Handy, Senior Regional Adviser, ISS Addis Ababa and Dakar.

Become an Insider

Become an Insider

Comments - Please login in order to comment.